Turbonique delivered the rocket cars that Detroit was afraid to build

The 1960s were steeped in the rocket age. The world lived in the shadow of the massive Saturn V boosters that had ostensibly been developed for peaceful space exploration, but also served to extend the reach of the American nuclear umbrella.

Intentions aside, the promise of a lunar landing and the existential dread imparted by Sputnik inspired an entire generation to look to the night sky. These were the kids who turned to the back pages of their comic books and issues of Mechanix Illustrated, greeted by a seemingly endless parade of Space-Age ephemera for sale. Buried there between the black market fireworks and questionable astronaut ice cream flavors was the Turbonique—perhaps the craziest aftermarket accessory ever developed for the automobile.

What made the Turbonique such an outlier? That is, as long as you consider strapping a rocket engine to the back of your car, filling it with a magical mail-order fuel, and then lighting its 1300-horsepower fuse to be a little over the top.

Rocket’s red glare

Ah, the rocket car. The marriage of America’s two greatest technological godheads at the time couldn’t have been a more natural impulse. While heavyweights like Chrysler couldn’t quite get its turbine-powered automobile ready for mass consumption, that didn’t discourage individual entrepreneurs like mechanical engineer Gene Middlebrooks from picking up where the Big Three left off.

To be fair, Middlebrooks wasn’t looking to build an entire vehicle around a jet engine, like the Chrysler Turbine, but rather leverage the untapped straight-line potential of 60,000-rpm booster pack. After having spent most of his career working on nuclear-tipped Pershing short-range missiles (which were deployed in the European theater), Middlebrooks got the racing bug and decided to take his enthusiasm for speed-of-sound projectiles to the streets.

To this end, in 1962, he formed Turbonique. The company operated out of Florida, a state only just then starting to develop its reputation for freedom and permissiveness (read: famously lax oversight). To describe the company’s business model as “unique” does a disservice to the word. Rather than simply building rocket pods that could be mounted to a vehicle’s fuselage and then presumably piloted by the criminally insane, Turbonique sold its customers on a variety of devices that made mad scientist mechanical links between jet tech and traditional automotive power-adders.

Your car is bursting in air

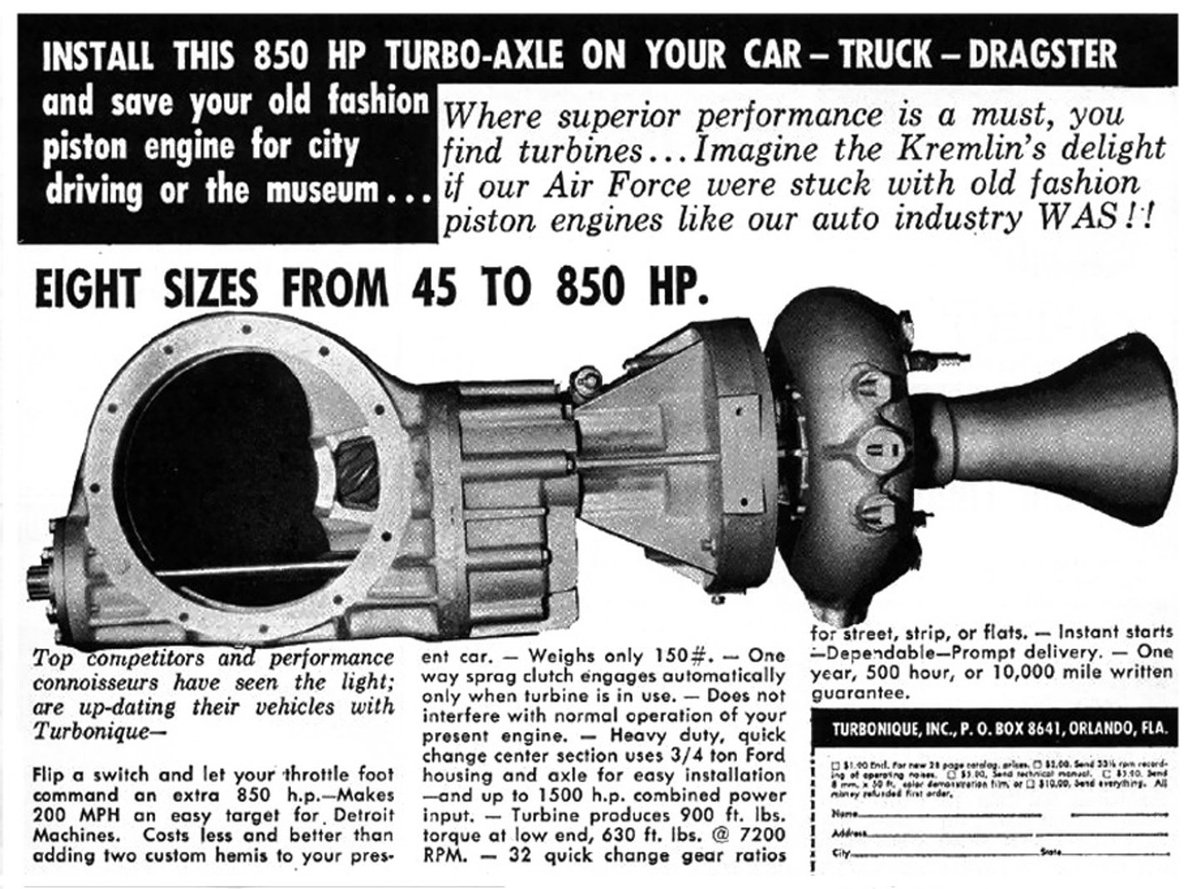

How did it work? That depended entirely on how much money you wanted to spend and how fast you were looking to go, but for the most part, each of Turbonique’s various products relied on the use of a microturbine that was spun up by the ignition of a proprietary fuel mix called “Thermolene.”

In reality, Thermolene was another name for isopropyl nitrate, a rocket propellant notable for the fact that it doesn’t require the presence of atmospheric oxygen in order to combust—making it ideal for use in space, and, um, your drag car. Thermolene used a chemical catalyst to kick-start a chain reaction that releases enough energy to seriously scare your neighbors and potentially melt your face off. In most Turbonique applications, this fiery enterprise then spun up microturbines of various sizes.

Turbonique was as creative with its applications as it was with it concept of driver safety. For those who were looking for all of the benefits of a supercharger with none of the complications like belts or a well-understood and time-tested design, it offered the

“Auxiliary Power” unit, which used its explosive concoction to force-feed compressed air directly into the engine intake with zero parasitic drag. It was advertised as being able to double the horsepower of most V-8 engines, and Middlebrooks had the dyno charts to prove it.

Not enough for you? No problem! Turbonique’s main claim to fame was its “drag axles,” which somehow managed to be even crazier. Picture a Thermolene-powered jet turbine attached to the rear axle of a muscle car that could add an astonishing 1300 horsepower on top of what the standard gas engine was sending back. Output was transmitted by way of a one-way clutch while spectacular flames shot out the back. Theoretically, your differential managed to resist similarly exploding with the force of a thousand suns.

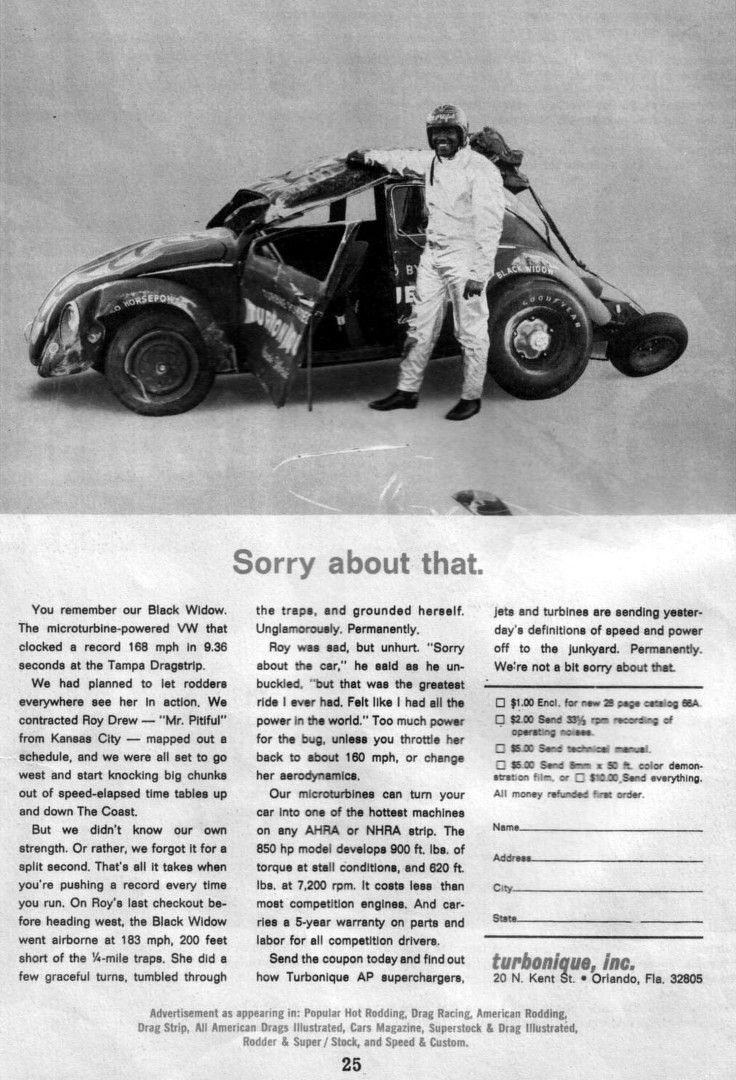

Despite a price tag reaching close to $5000, there were several takers among drivers seeking a competitive edge. Some drag axle-equipped cars (in particular, the aptly-named ‘Black Widow’ VW Beetle) topped 180 mph at the strip, a fact that the company repeated over and over in its advertisements.

In another shade of brilliance, control of any Turbonique system relied entirely on cutting fuel delivery, which meant there was no throttle control whatsoever—just an on/off switch that swung you from “normal” to “ludicrous” speed by way of a spark plug in the ignition chamber that set the Thermolene charge ablaze. This approach was significantly different from traditional turbine designs, which gulped down atmospheric air. While it helped make Middlebrooks’ microturbines remarkably lightweight and efficient, it also contributed to a situation where fuel build-up could create out-of-control explosive conditions inside the system. Fun!

Oh, and remember when we said there weren’t any “rocket pods” for sale from Turbonique? Well, that’s only kind of true. Although Turbonique didn’t officially market them for automotive use, you could buy a range of “thrust” engines ranging from the T-16 all the way up to the T-32, with the lesser model providing a whopping 300 horsepower.

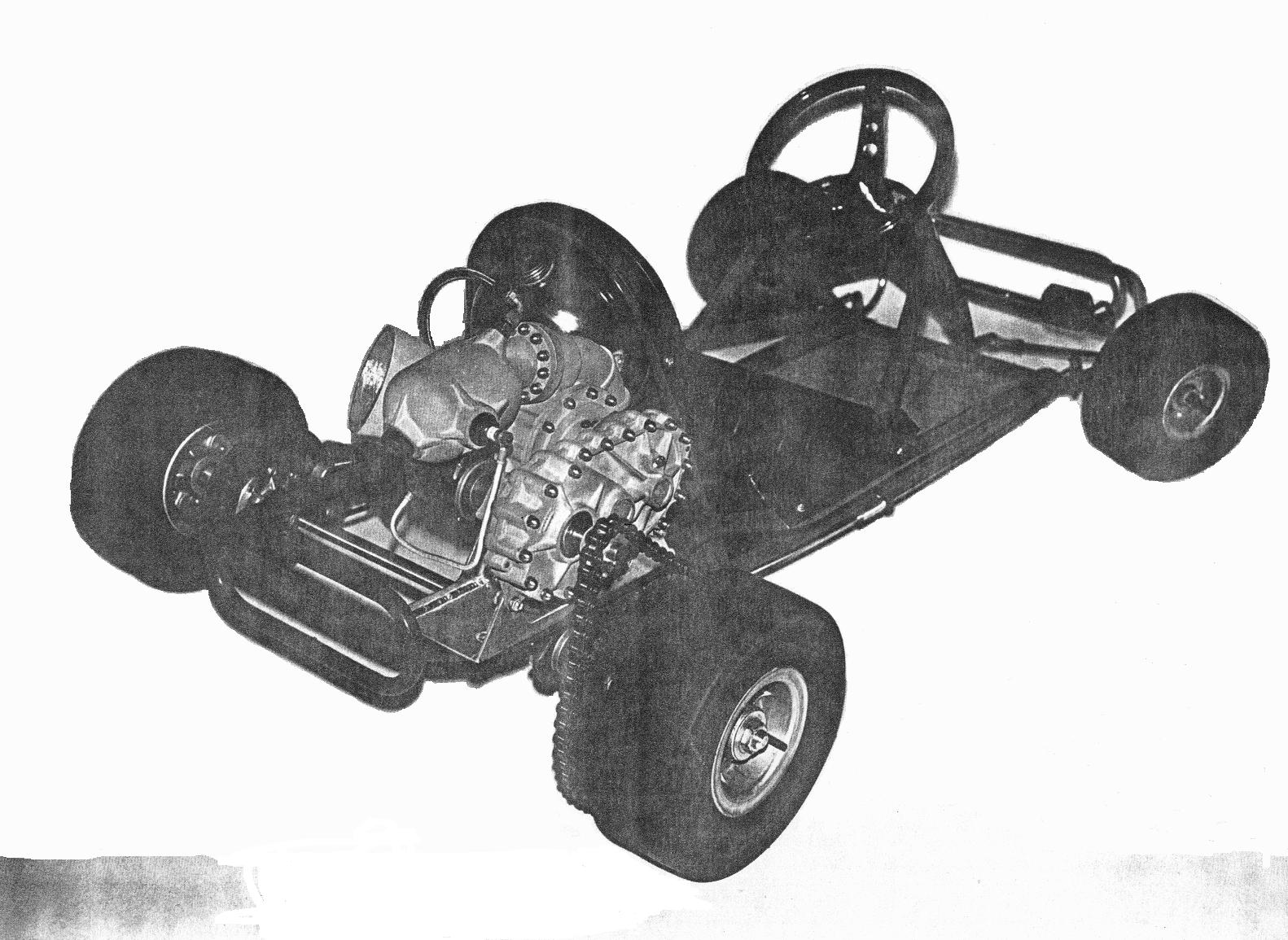

Such setups were used by boats and by a few brave souls willing to push land speed limits in cars and motorcycles. There was also a man named Captain Jack McClure (note: not a real captain), who added them on a West End go-kart which he would later race against legendary drag driver Tommy Ivo. His description of the installation is harrowing:

“This was the first time two Turbonique T-16 engines were fired at the same time,” he says on his eponymous website. “There was a small fire after the engines shut down.” Unable to locate Middlebrooks after the initial start up, he later found him cowering on the other side of a railroad car. “I asked him why he was behind the railroad car [and] he said, “Because I have a wife and two kids.'”

They flew through the night

Predictably, things did not end well for Turbonique. While all of the above sounds like a litigation nightmare from a modern perspective, in the ’60s, the legal environment concerning liability was a little more lenient, and as such, it took several years before the various small disasters wrought by mail-order rocketry caught up to Middlebrooks.

It started out with the NHRA banning the drag axle from competition, citing a number of incidents that called its safety into question. Why those concerns weren’t voiced the very second the first Turbonique showed up at the track—or an NHRA official read the company’s brochure—isn’t clear. Next, customers began to complain that the plans they received for their self-assembled rocket engines were substantially more difficult to execute than they had been made to believe, and that locating crucial parts was costing them an arm and a leg. This was all on top of the perils of selling 55-gallon drums of isopropyl nitrate through the mail.

By the end of the decade, Middlebrooks had been hauled before the courts on counts of mail fraud, and as one might expect, his decision to act as his own counsel didn’t stave off a conviction. Middlebrooks died in 2005, but the Turbonique drag axles live on in legend, with units occasionally coming up for sale at auction. Now, if we could just find a barrel of Thermolene…