Media | Articles

Prepping my Moskvich for escape to America was a bureaucratic adventure

Matthew Anderson is an American engineer who relocated to Germany a few years ago for work. In his spare time, with reckless abandon, he pursues a baffling obsession with unexceptional Eastern Bloc cars. We don’t ask him too many follow-up questions.

As they say, “if you leave it to the last minute, it only takes a minute.” They also say “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” For better or for worse, both apply here: I found myself in the utterly illogical reasonable position of readying my Moskvich in time for my journey across the Atlantic, returning to home in America, just days before I was set to leave Germany.

What’s more, I could only afford “roll-on-roll-off” shipping, which means the Moskie would be hustled around a busy port and interior of a ship with a hurried dock worker at the wheel. I was not going to be there to limp it along under careful piloting, managing its little Soviet idiosyncrasies. Then there’s the paperwork: I needed vehicle documents in my name for importation. And with our wheels-up date for three months across southern Europe in the Wohnmobile set to kick off just 10 days from this point, how was this all going to work?!

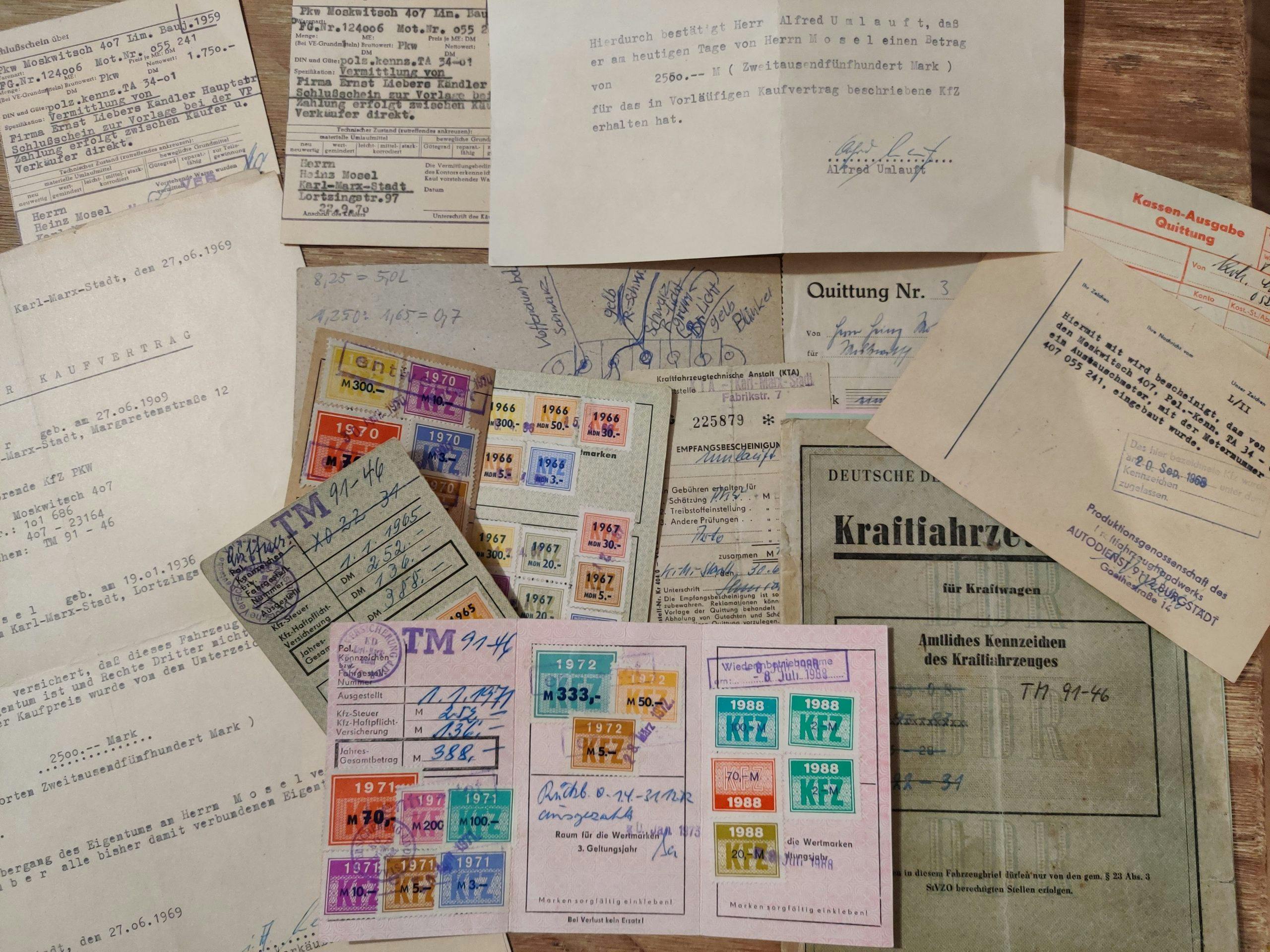

Let’s start with the paperwork problem. We are dealing with an East German vehicle title under the name of a deceased resident of a collapsed regime that was last stamped by the Volkspolizei in 1968. So, probably not something that the North Carolina DMV is going to be equipped to handle. Even if it were, going through that process would mean destroying the original title—a most important piece of the car’s history—in order get a clean, flavorless NC document. Avoiding this meant a huge amount of work on my end. Why? A new title requires a certificate of roadworthiness. Enter the TÜV (German technical inspection association) and its notoriously picky and, annoyingly, incorruptible inspectors.

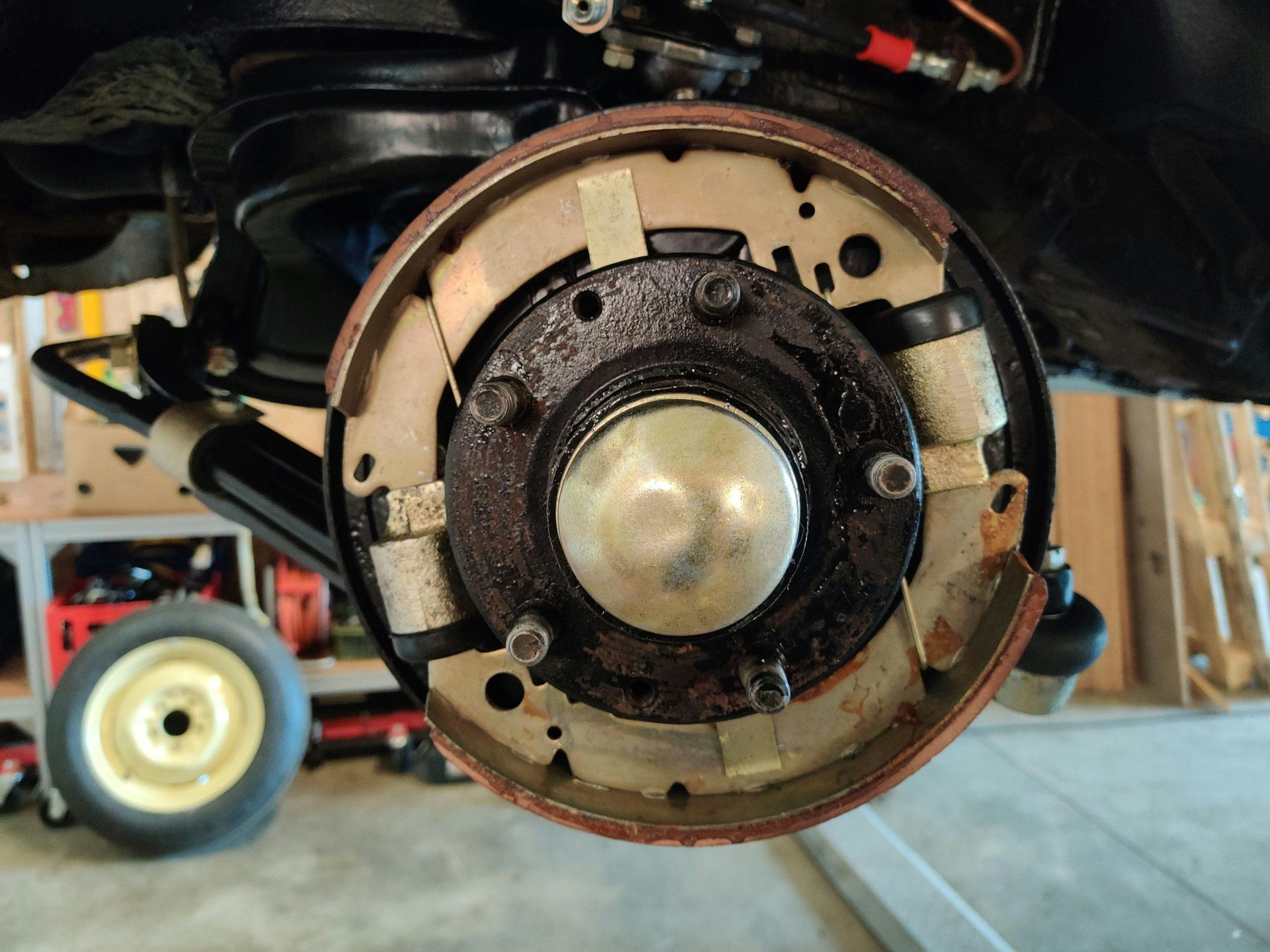

The first step to get approval was simply assembling the parts I had. About 10 minutes into the brake assembly job, I discovered I had the wrong parts yet again. As it turns out, 19mm wheel cylinder pistons in a 22mm hole don’t even meet my laughable standards, let alone those of German bureaucracy. My buddy Patrick came to the rescue; a couple hours later I had hot, fresh parts. Now that the brake hydraulics could be rebuilt, lines run, and the drums roughly adjusted, the Moskie came down onto its haunches for the first time in a while.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

I needed to verify that the motor would run up to temperature without locking up or smoking out an entire RoRo vessel. I’ve been living near elderly neighbors, so running it with open exhaust wasn’t an option, even on days that weren’t Sunday. The next order of business was muting the noise. Let it be known that I hate exhaust work, mainly because I suck at it. For a lifetime fix, I elected to spend big bucks on 40mm diameter stainless. About $250 later, I had all the tubes, bends, hangers, donuts, and stainless MIG wire I could foresee needing. I even found a ready-made generic 40mm axle loop! Let’s get to spattering! Thanks to measuring the bends ahead of time, the system was finished in a couple hours. It can even come back out without a Sawzall!

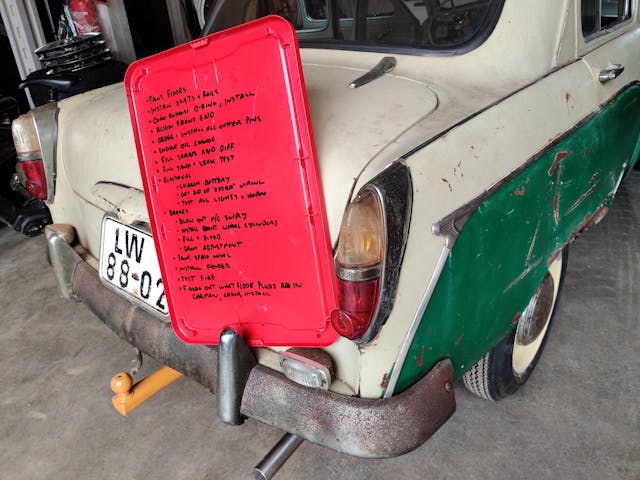

Now it was time to assess the motor! Having gotten a few rotations out of it some months ago, I didn’t have major anxiety that it wouldn’t at least start. What scared me more was the prospect of massive oil leaks, incessant smoking, or lack of oil pressure when warm. I did a quick re-sanding of the points, installed an NOS lower radiator hose, and connected the previously working battery from my now-flat Skoda Favorit, and turned the key. Nothing. I smacked on the starter with a mallet, hot-wired the solenoid, twisted the terminals, and still nothing. For now, the hand crank would have to do and the rest got scribbled on my Rubbermaid lid to-do list. The kick-back on that first try indicated to me that the ignition was working just fine. I reached way down in the guts of the engine bay to prime the fuel pump and fill the float bowl, just in case this could actually work. On the third rotation, it lit right off and spit the hand crank out. A few manual actuations of the throttle blade later and it had fully cleared its throat.

Good oil pressure and only one major oil leak! Swapping out the seal on the oil filter canister fixed that. We were good to go in the motor department!

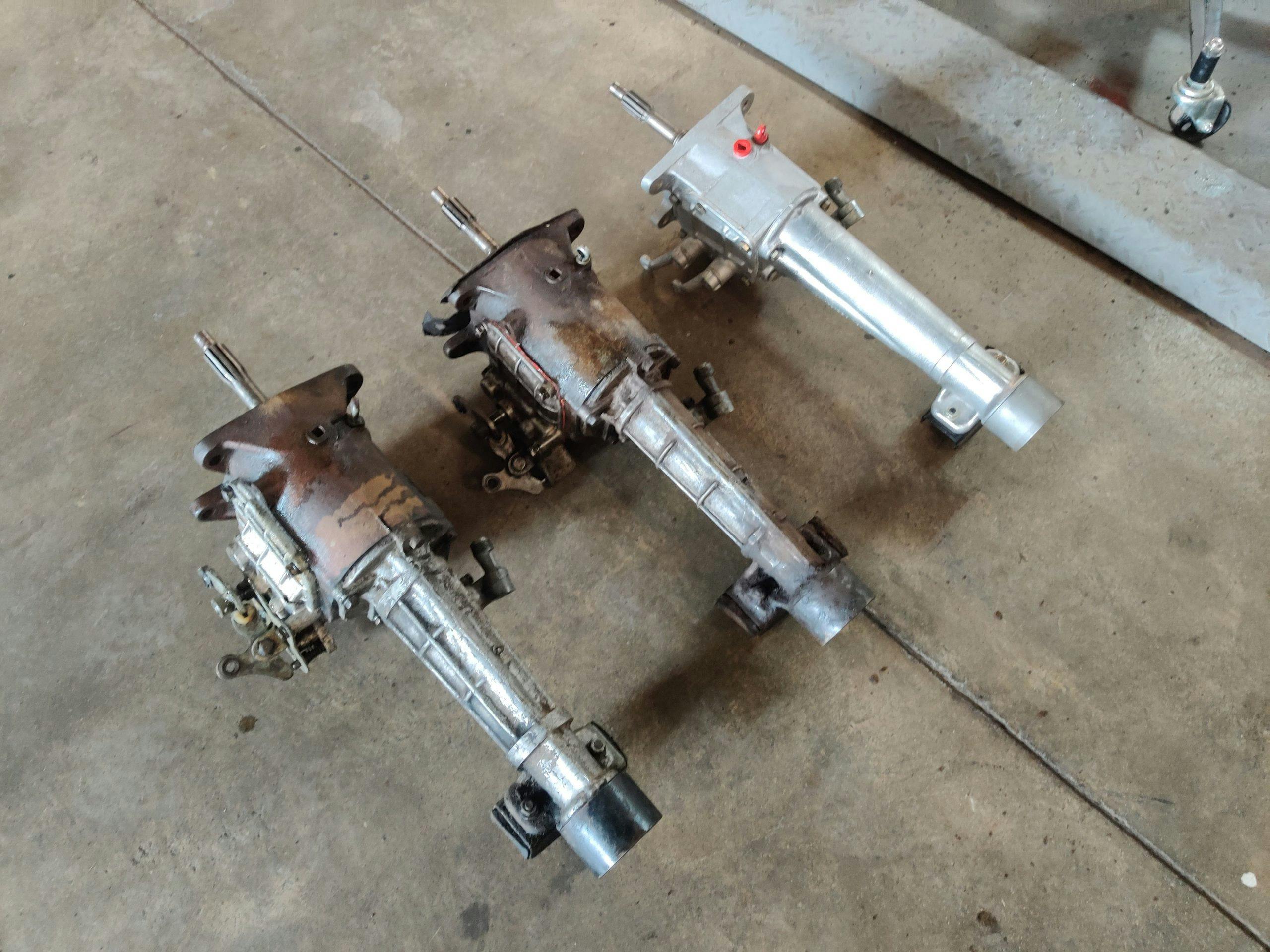

Upon trying to move the car around the shop, it appeared that I had only reverse and third gear. Yikes. Again, for me this would’ve been ok. For the port worker dude would be a recipe for a revenge-roasted clutch or worse, no embarkation. I begrudgingly removed my new exhaust and old column-shift four-speed transmission, a process all made easier by a broken mounting ear and missing fourth bolt. A quick peek under the covers showed a jammed shift fork. I freed it but still didn’t trust it. And then, some long-awaited redemption from the absolute worst car purchase I’ve ever made. Welcome back to the top step of the podium, bargain-basement Jaguar XJR! I tapped a new output seal in, made a new input shaft gasket, and we were in business. Shift pattern? That’s anyone’s guess, including the TÜV prufer.

Ok, where are we? Brakes work, gears work, motor runs. Ah, right, it can’t have any holes in the body!

One of the most special parts about this barn-dwelling Moskie is its patina. I had to weld up the fenders, rockers, and wheel arches in a way that really made it look like it was leaded in an East German barn in the 1960s. No modern stuff, just metal and rust that you can’t jam a screwdriver through. Even if it looked terrible, it would be better than filler. The deeper I dug, the worse it got. The inner rear fenders were torched, not just the outers. And not just the inners, but the one jack point I hadn’t replaced yet was also rotten as a pear. It was entirely too late to turn back. On my sixth or seventh day straight working late nights, my angle grinder with purple paint stripper disk rebelled and tried its removal skills on my face. Visits to the eye doctor, extreme light sensitivity, and lots of scabs were to follow.

But ugliness, blindness, and pain couldn’t stop me. I had only three days left in Germany and the show must go on. Feeling confident that the car could run, shift, and stop while retaining its passengers inside the bodywork, I was ready for the inspector’s visit on Thursday. I would need that report in just two days in order to make it to my time slot at the city hall—and there would be only one shot.

Shortly after our house was containerized and we moved into the camper (more on that in a future story), I got a distressing call from the workshop. TÜV said that the vehicle numbers didn’t match my title. It appeared that preservation of the whole vehicle might not be possible, not just the documentation. Discouraged, I canceled my appointment at the city hall. After a few hours of research, translation, and paint removal by the workshop, the correct numbers were located on the chassis, and they did indeed jive with the papers and the VIN plate, a task made difficult by corroded Cyrillic etching. A second call came: it passed! I raced over to pick up the documents before some other injury befell me. But blast it all to hell, now I don’t have an appointment!

I decided to try anyway. The next morning needed to go perfectly. It was the last (canceled) appointment of the day at the city hall. Getting a city employee in Germany to serve a canceled appointment on a beautiful Friday afternoon? Unlikely. But if it didn’t work now, it may never. I made sure my shirt was extra non-wrinkly and my shoes had the most closed toes possible. I was fastidiously organized with a binder with every piece of paper that tied me to the car, and the car to roadworthiness in the anticipated order in which they would be requested. I would out-German these Germans.

After talking my way through building security and then the information desk, I found a worker who was either sympathetic to my facial wounds or wanted to be fashionably late to her Friday plans. Late she would be, indeed. When I presented the DDR title, she held it by the edges like the historically relevant document it was. Enter supervisor. Now there were two detail and process-oriented people who hadn’t a clue how to proceed. About 15 minutes into the document conversion, she kindly requested that I come back next week; there was a problem in which the rpm at which the maximum power was delivered was not entered on the TÜV report. TÜV was on lunch break and no one was available. They were sorry. They tried.

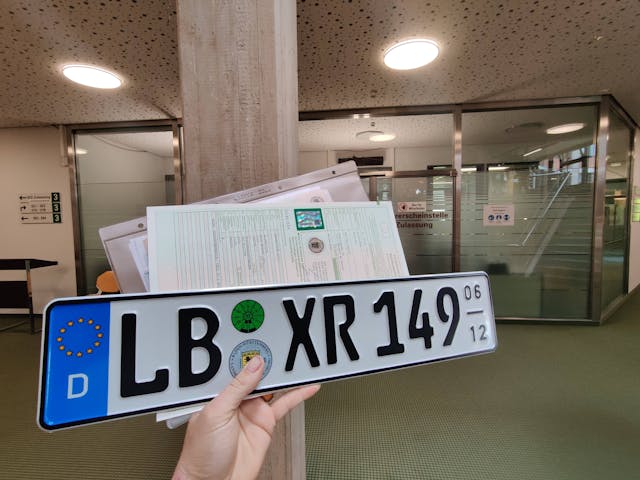

I don’t know whether it was my eye twitching or insistence that I have an owner’s manual in my car (or from Google Images) in which I could consult for the proper rpm value, but they somehow processed the paperwork without it while I frantically Googled in the 4G reception-enabled courtyard. I finally had the last piece of the puzzle: A genuine vehicle title for a 50-year-dormant Moskvich from gloriously reunited Germany.

So now what? I’ve got a spot booked on a ship. The car remains at the workshop now for some last-minute hardening to port driving, followed by a brief hibernation before setting sail for Statesville, North Carolina, via Bremerhaven and Charleston, South Carolina. With a sigh of relief probably audible in the former DDR, I can report that though it almost killed me, the Moskvich project—from barn to TÜV—is hopefully finished.

Did it kill me? Nearly. Did it make me stronger? If being more conservative in planning is a strength, then absolutely.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Hopefully the Statesville DMV will not give you a hard time. If they do come to Lenoir and we’ll try to help.

I’m just starting on a 407 that has no docs- so found this really useful! Do you know where the chassis numbers are etched, please – as right now I have no vin plate! Thanks