Old-school British shop molds transportation’s past, present, future

To honor the uniquely British craft of this shop, we have retained a U.K. vocabulary but adjusted spelling to reflect an American lexicon. —Ed.

It’s often said that Britain no longer makes stuff. Yes, we make Japanese cars, and bits and pieces of electronickry, but not your good old Victorian fire, smoke, and hammers type of making stuff. But a visit to visit Grainger & Worrall in Bridgnorth, Shropshire, will convince naysayers otherwise. Here you will find cauldrons of molten aluminum, shiny silver like mercury at 750 degrees centigrade (1382° F), ready to be poured into molds that when cooled will be broken open to reveal anything from intricate castings to large engine blocks.

Jay Schofield, head of sales and marketing at Grainger & Worrall, is giving Hagerty a guided tour of this incredible place. A large number of the world’s car companies knock on G&W’s door, many of whom require utmost discretion from the company. Not all of them, however—and many of the parts made by G&W are not difficult for the knowledgeable enthusiast to recognize.

For example, we are looking at a crankcase which has sixteen cylinders arranged in a W configuration: It is clearly destined for the rear of a Bugatti Chiron. Grainger & Worrall has made all of the engine cases for Bugatti from the Veyron onwards. But the hypercar maker is not the only customer from the Volkswagen Group.

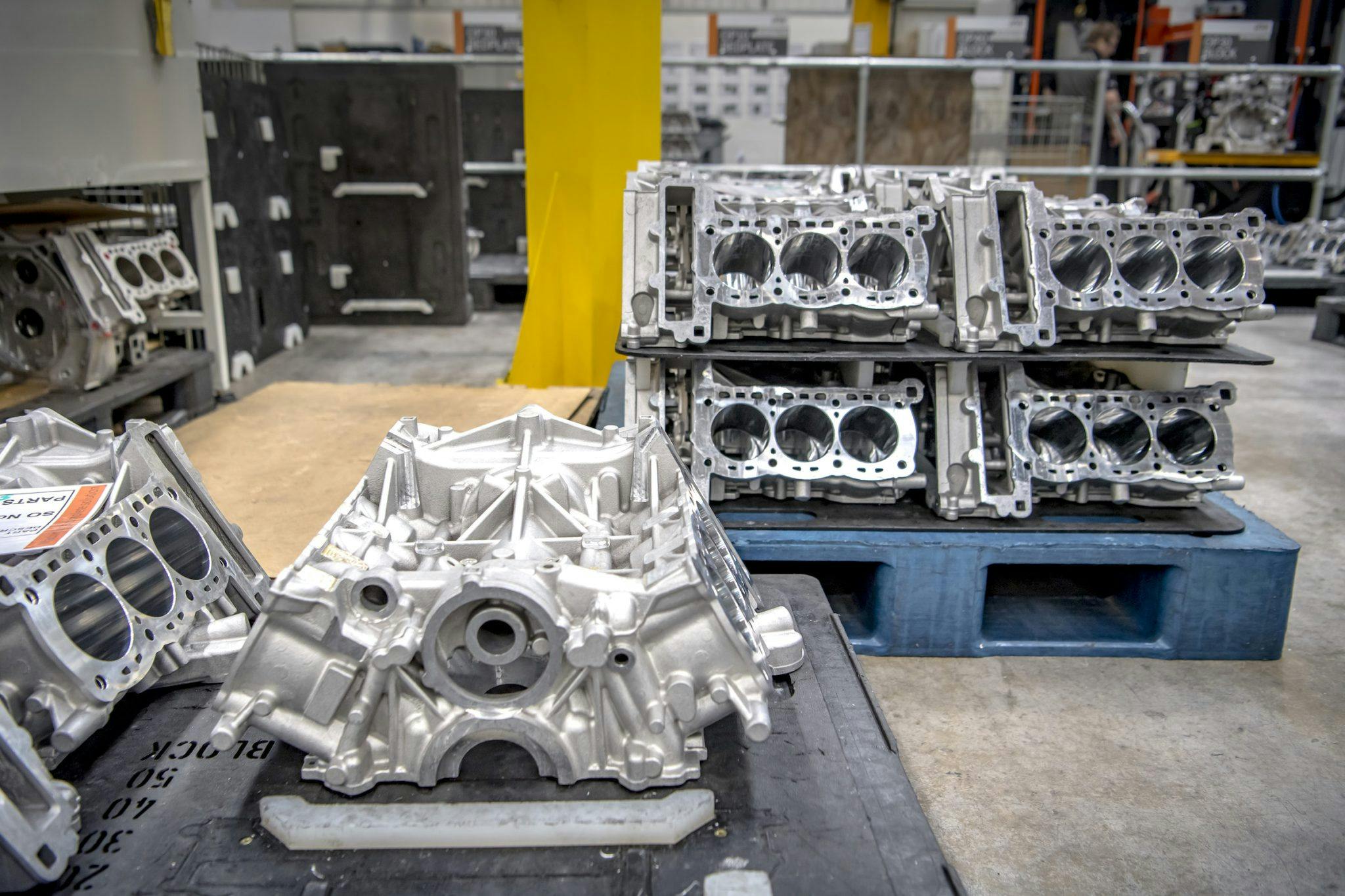

It triggers warm patriotic feelings when Schofield points to rows of Porsche flat-six crankcases on pallets. They’re for Porsche’s GT-series engines, such as those fitted to the GT3 and GT3 RS and the new Cayman GT4 RS.

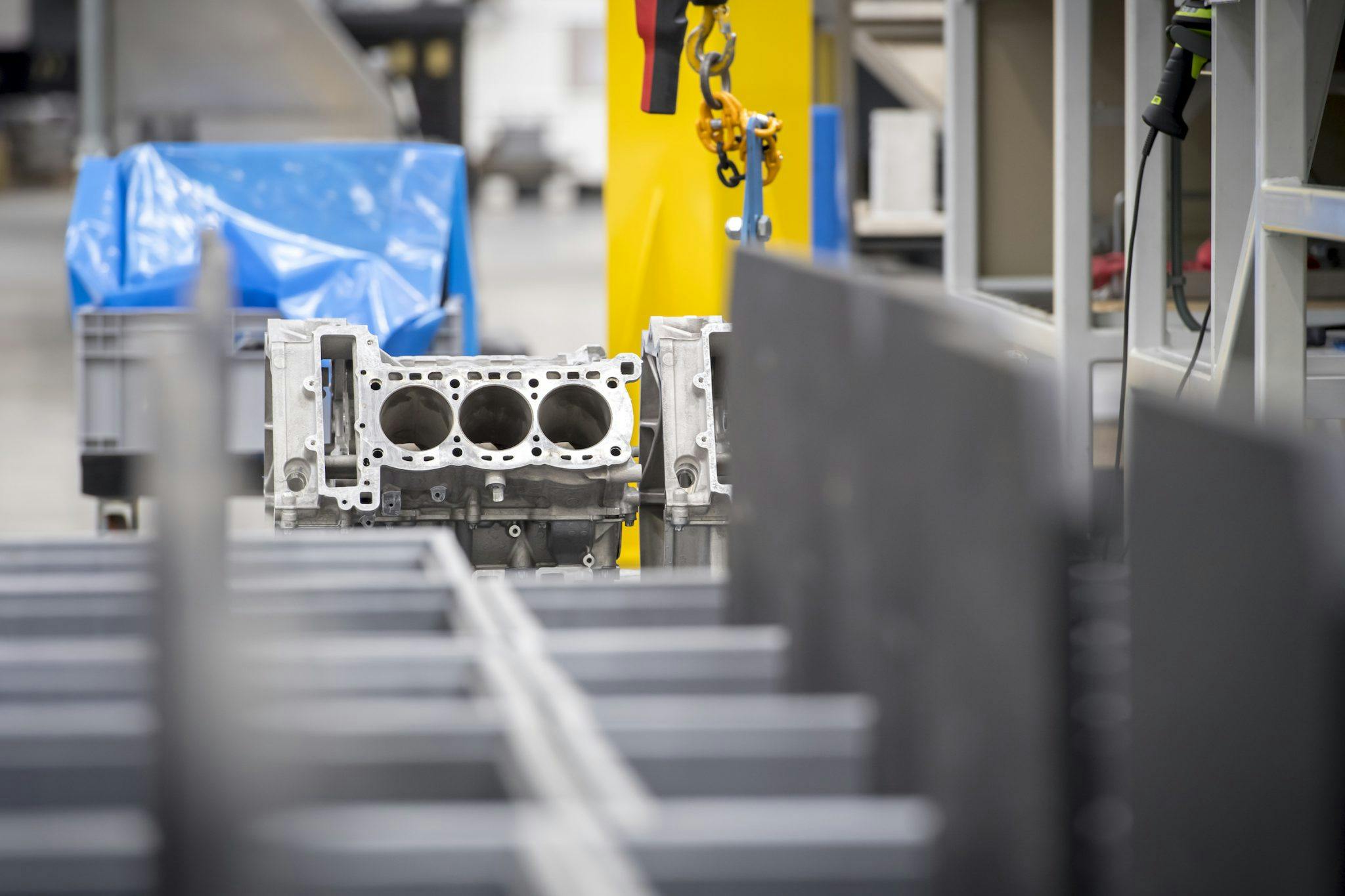

McLaren is another long-term customer for whom G&W has cast V-8 blocks since the Woking sports-car concern launched its MP4-12C over a decade ago. Later, when we visit the enormous, new machine shop that was opened only five years ago, we will see rows of V-6 engine blocks that are the heart of the new hybrid engine that’s going in the new McLaren Artura and, no doubt future, models. These blocks are not to be confused with a similar, V-6 crankcase that is made here for Maserati, for the Modenese company’s MC20 supercar.

The real secrets hidden within G&W’s substantial premises are the multitude of commissions from some of the world’s best-known names in motorsport. Schofield isn’t allowed to let us sneak even a couple of millimeters of nose between the doors of the motorsport department. That said, I have visited many F1 teams over the years. I can recognize the odd F1 engine part when I see it and have already spotted a wooded crate containing what look suspiciously like water pumps for an F1 engine. No doubt a man called Lewis would recognize them too. The two-wheeled world is also no stranger to G&W with several Moto GP teams using the skills available within these walls.

Grainger & Worrall was founded just after the war by Vernon Grainger and his brother-in-law Charles Worrall. Although the company retains the original name it is now entirely owned by the Grainger family and is run by Vernon’s grandsons James, Edward, and Matthew. And the family really does own the company; they’re not bankrolled by some big-shot financiers who would think a capstan lathe was a brand of cigarette.

Eighty percent of the castings are in aluminum using around 40 different alloys. The remaining 20 per cent of the work is in ferrous metal. One such product is a V-8, cast-iron crankcase that carries a Ford logo and is used in NASCAR racing. G&W has been supplying blocks for various teams involved in the American stock car series. Before they did so, teams used to get through around 1000 blocks per season, but now, thanks to the Bridgnorth company’s skills, only a quarter of that number are used.

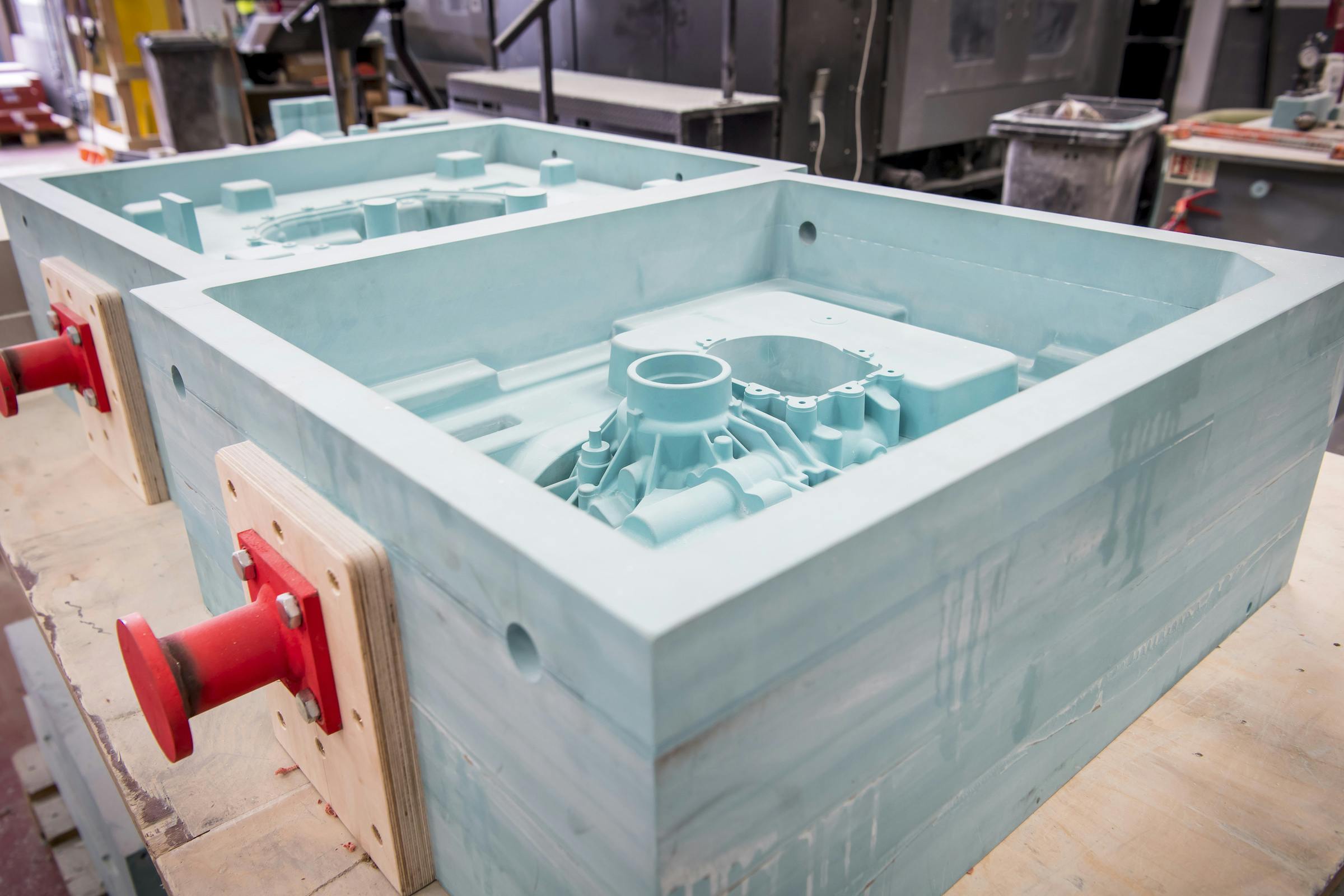

The foundry or casting departments are split into two; one is for low-volume production and the other is for series production. In the first we see half-a-dozen large molds that are used to cast V-8 blocks for Bentley. These blocks will be held as spares for the now out-of-production 6.75-liter, pushrod engine. Each mold for an engine of this size comprises about a dozen or more individual molds bonded together to form the whole. The molds themselves are created from patterns. Patterns used to be made from hardwood, a material that required a combination of great skill and much time.

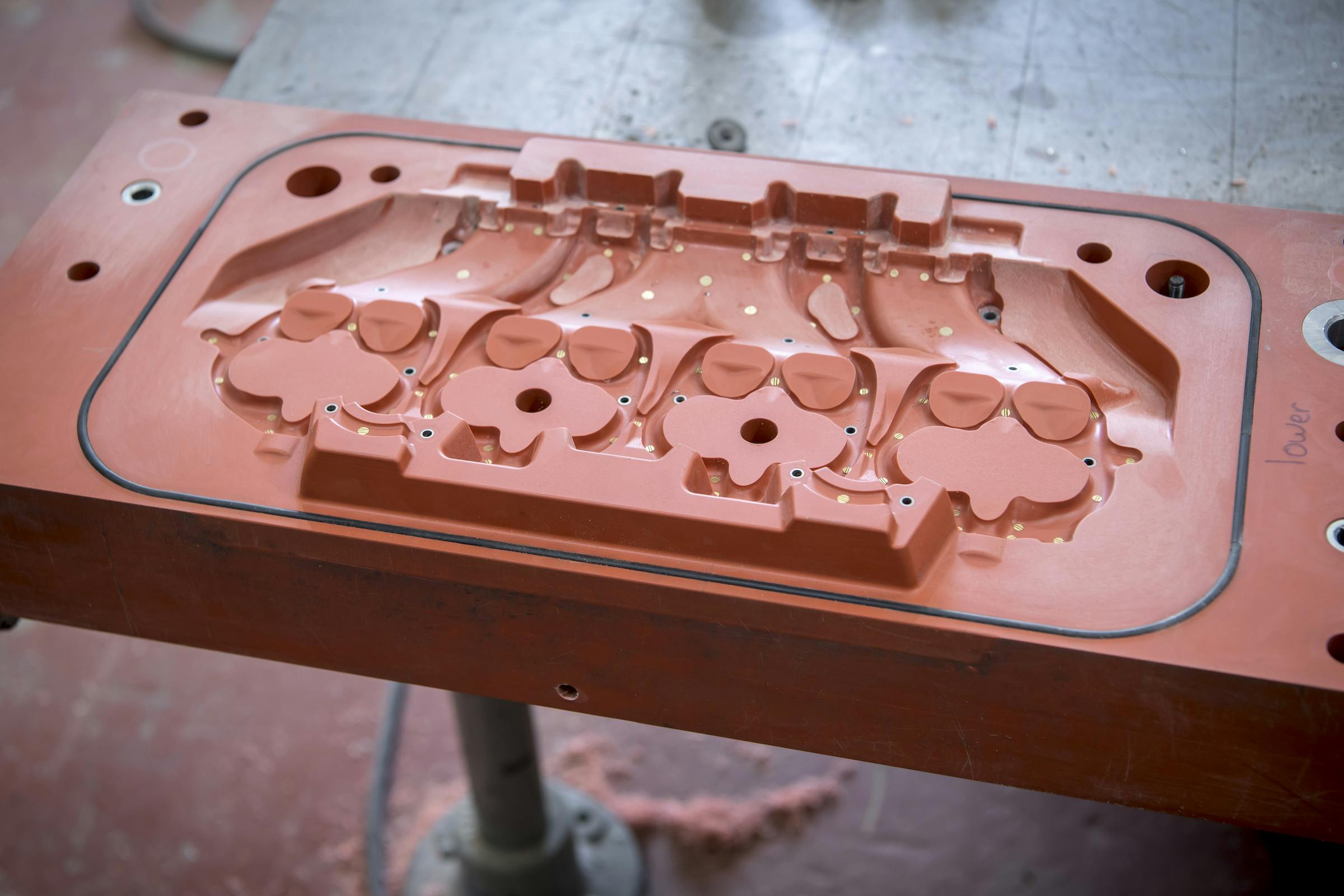

In the past it could take six months to produce a new component. Today, using techniques similar to 3D printing, a prototype pattern can be made in a matter of hours. Once series-production is started, patterns are made out of a composite material that is CNC-machined. The color of the material used denotes the lifespan of the pattern, with a dark, ruddy brown indicating a pattern that will be able to produce thousands of molds.

In the series-production casting area, robots are used to pour the molten metal into the molds; but in the low volume area, which in truth is the more interesting place, people are doing the work. Thirty-five years ago, I worked in an iron foundry in a placed called Toowoomba in Queensland, Australia. Tough work: A blast furnace feet away brewing up iron and steel at over 1500° centigrade (2732° F), hotter for high-strength steel, and in ambient temperatures approaching 40° C (104° F). We cast stuff like lorry brake drums, master cylinders for cars, and lots more. Health and safety was minimal in those days …

For small components the molten alloy can be spooned into the molds with a large ladle, but for these big, V-8 Bentley engine blocks, the cauldron itself is lifted by an electric hoist then carefully tipped into the top of the mold. With a large component such as these crankcases, it takes several hours for the alloy to have cooled enough for the mold to be broken away. The sand used in the mold, a special type, will be recycled and used again, the epoxy that it contains to join the various sections burnt away during the process.

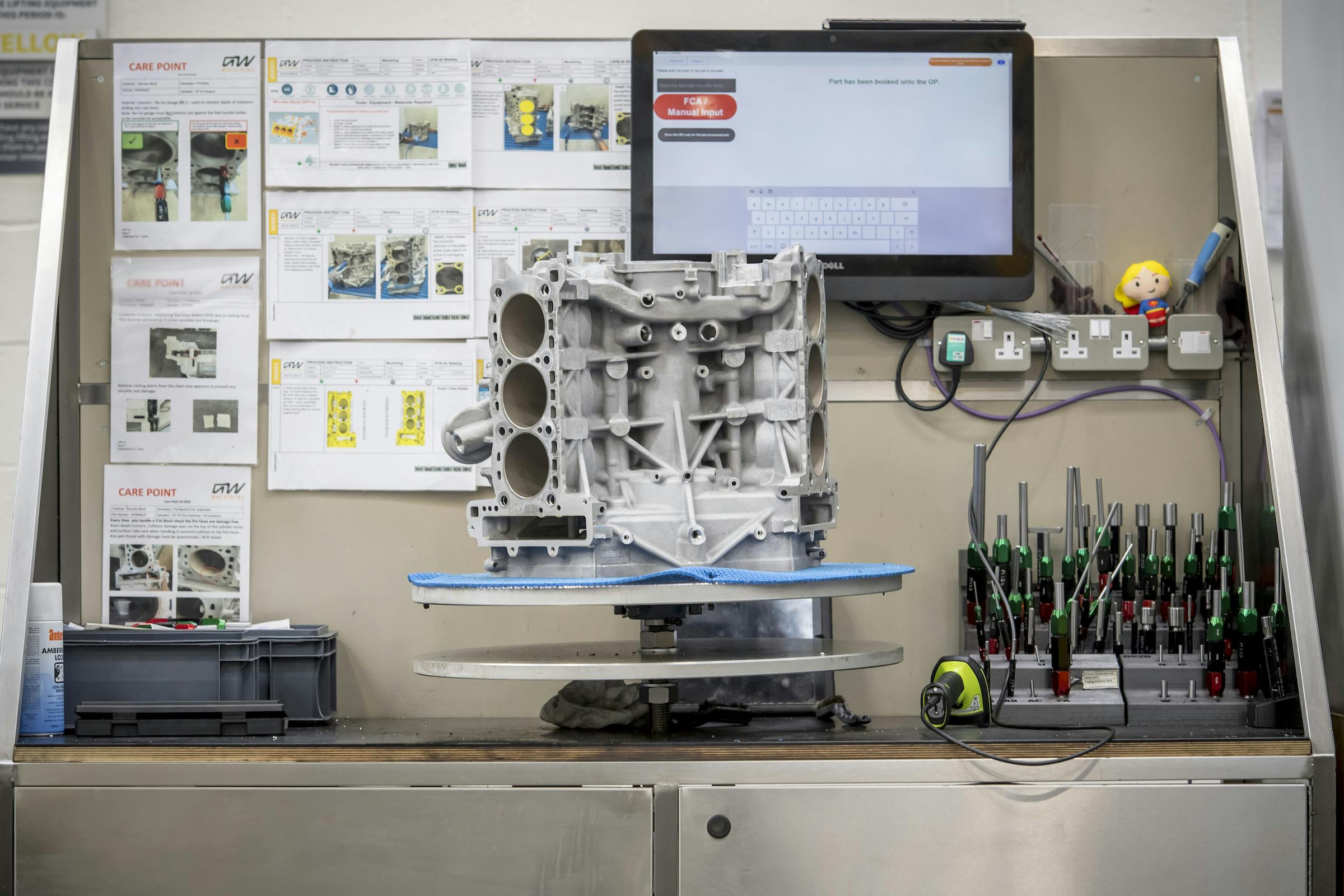

The finished block, cleaned of sand, will now go to G&W’s machine shop. The company has always had machining facilities but five years ago opened a giant new facility just a couple of hundred meters from the foundries. G&W offers a variety of services to customers from complete machining to, say, simply milling the mating faces of a cylinder block. Everywhere you look are state-of-the-art CNC machines, each capable of carrying out a multitude of tasks, automatically selecting tools with which to do so.

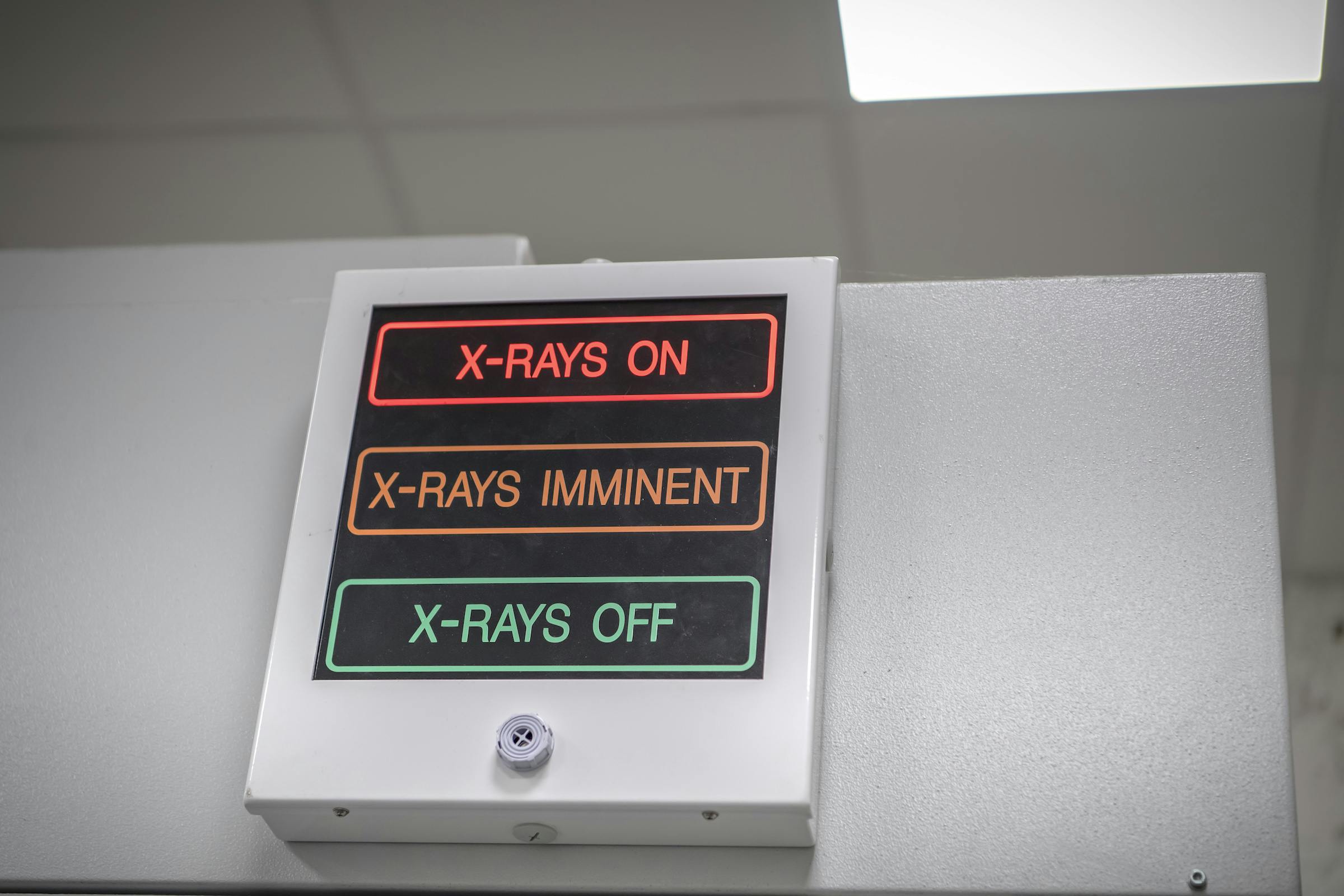

There’s another department, far removed from the fire and brimstone of the casting works and the swarf and machine oil of the machining department, that’s just as fascinating. This is the design department, responsible for prototyping and, in many cases, reverse-engineering components. Among G&W’s OEM clients are those who make “continuation” versions of their back catalog of classics. I’m sure you can guess the names and models of a few.

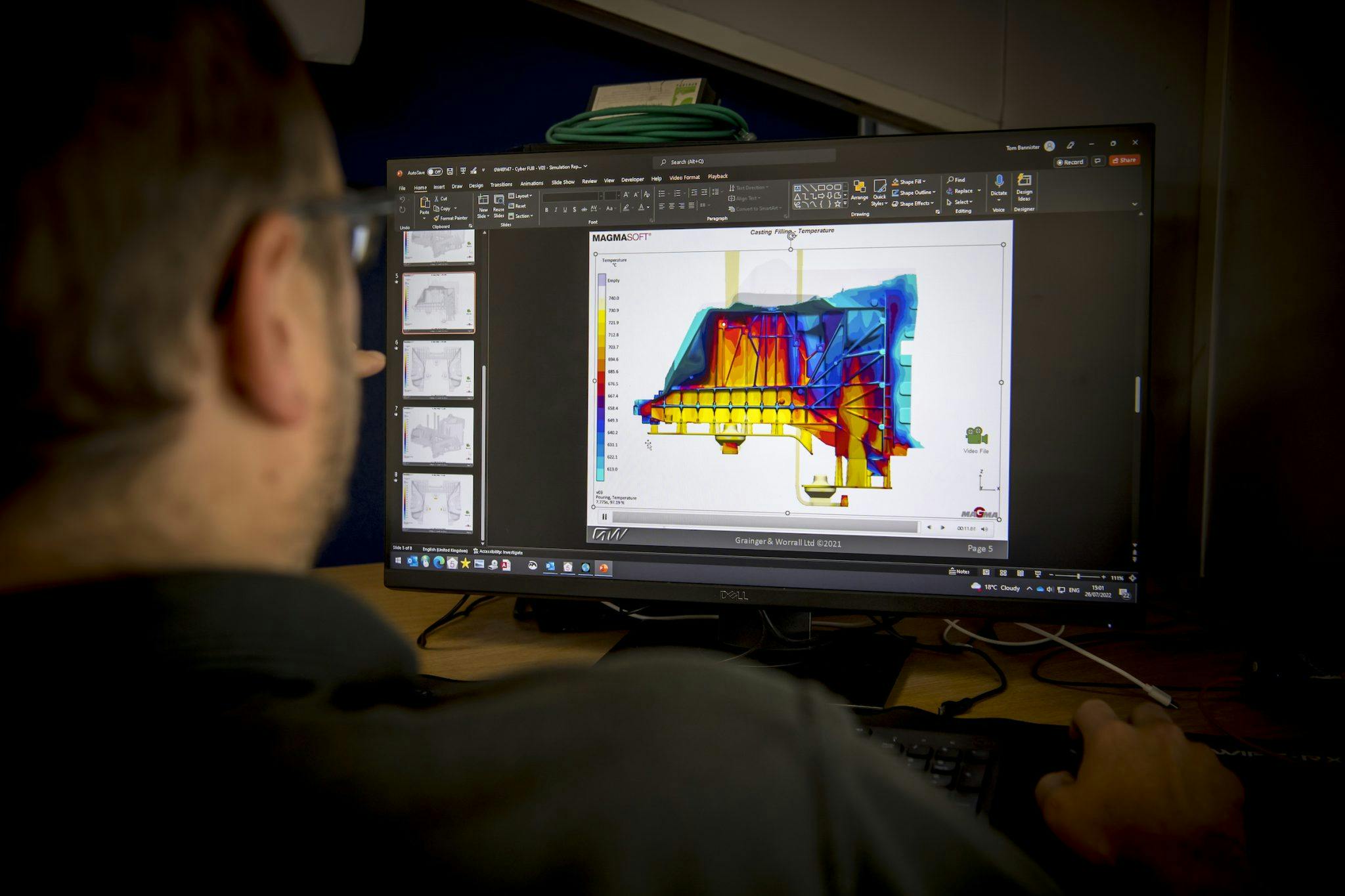

Here I’m told something so remarkable that I struggle to get my head around it. At a desk, an engineer is running a program that simulates the flow of molten metal through and around a mold. The goal is to have the metal enter the mold and fill it at a consistent temperature. Hot or cold spots are to be prevented, as these can lead to weaknesses or failure points within the part. In the modern world we’re used to computers being able to carry out tremendously complicated calculations in seconds. Get this: Although the computer on which the simulation program is running is very powerful, it can take it almost as long as a week to complete all the simulation required for a complicated part.

One thing has been worrying me, as we’ve been walking around looking at fantastically intricate engine parts and wonderful assemblies like the Bugatti W-16 cylinder blocks. What happens to Grainger & Worrall after the electrification revolution that’s taking over the car world?

Schofield leads me to a part of the new machine shop where there are pallets of large-diameter, alluvium castings. “These are electric motor units for a large, U.K.-based OEM,” he explains. There’s more: Schofield is particularly proud of the fact that Tesla used G&W for prototype casting for the huge, front-end assembly used in the Model 3 and Model Y. This is no secret, as there’s a complete example of the structure in the company’s reception area.

Grainger & Worrall is one of the most fascinating establishments that I’ve ever visited. It is a place of remarkable contrasts. A place where the past lives alongside the future. No better example is the brand-new, Rolls-Royce Merlin cylinder heads that the company has produced for owners of Spitfires and Hurricanes and other warbirds that use the iconic, V-12 aero engine, and the prototyping work being carried out for the electric cars that will be in showrooms within a few years.

Next time someone grumbles about disappearing skills in this country, it will give me great pleasure to tell them about Grainger & Worrall, just one example of our automotive industry delivering world-class work.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Very cool foundry, very tough work and maybe not the first place an 18-year old bloke would consider a career in. Too bad for him/her.