A Rat’s Life: Chevy big-block V-8s thrived for over half a century

Don Sherman’s latest entry in our Epic Engines series honors one of America’s best-loved powerplants. For deep dives on the small-block Chevy, Jaguar straight-six, Cadillac V-16, Chrysler Hemi V-8, read more here. -EW

After Chevrolet’s beloved small-block of 1955 earned its Mouse Motor alias, it was inevitable that its younger, larger brother would be called the Rat, if only to distinguish these two Chevy V-8s. Knowing there’s nothing rodent-like about either engine, enthusiasts took these pet names in stride.

In 1958, still celebrating postwar prosperity with ever larger cars, Chevy dumped the dowdy 150 and 210 model names of 1957 and jazzed them up as the Delray and the Biscayne, adding the Impala sport coupe as a sub-model of the top-of-the-line Bel Air. There were 10 separate body styles, with the Blue Flame six as the base engine and a 283 small-block V-8 teamed as the power upgrade, plus an all-new 348-cube V-8 that GM called its W engine, created to empower Chevy’s ambitious longer, lower, wider stratagem.

When engineers working under the direction of their hard-charging leader, Ed Cole, first fleshed out the small-block V-8’s specs in 1952, they deliberately left room in the block to grow. Given the bore spacing and the amount of cooling capacity in the block, the original 265 was thought to be capable of expanding to 302 cubic inches over what was expected to be the engine’s 10-year production run. In hindsight, it’s a quaint notion given that the basic design is still in production nearly 70 years later and its factory displacement peaked at 428 cubic inches in the 2006 LS7, the stroke stretched beyond Cole’s wildest imagination and the bores so enlarged there was no space for coolant flow between them.

However, back in the mid-’50s, it was believed that a whole new engine would be needed for the larger and more powerful cars that Chevy was planning. America was on top, gas was cheap, and a transnational freeway system was under construction that could whisk a fast car across multiple state lines in a matter of hours. Buyers wanted horsepower, and Chevy’s answer for 1958 was the W—which could have stood for weird, considering this engine’s departures from convention.

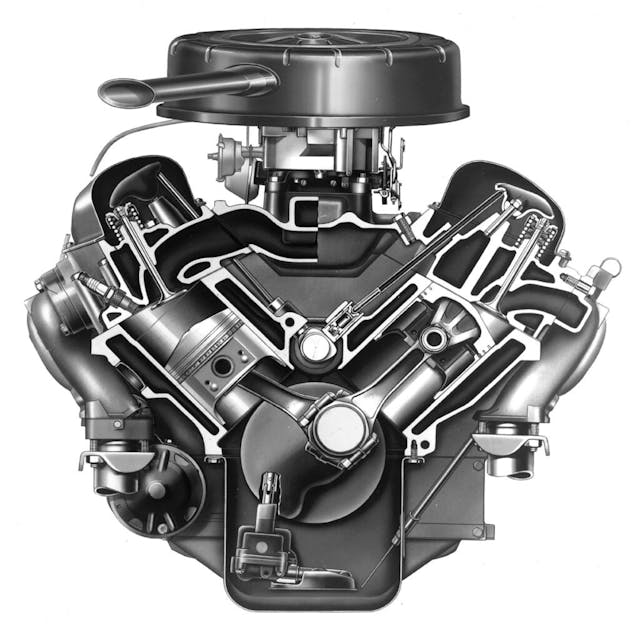

Among its oddities were completely flat-bottomed cylinder heads, the combustion “chambers” not scallops in the head but rather just the void between the head and the piston top. Obviously, this was easier to manufacture as the heads required less casting and machining work, but it was also thought to aid power.

The odd chamber arrangement was achieved by planing the block deck differently from conventional engines. Normally, the deck—the top of the cylinders where the engine block meets the head—is perpendicular, or 90 degrees, to the direction of piston travel. For the W, Chevy tilted the block decks in the design, slanting them inward toward the engine’s centerline. The W’s block casting had decks inclined 74 degrees to piston travel rather than 90, creating a 16-degree “wedge” shape for the void between the piston and the head that served as the combustion chamber.

The second oddity of the W was that the outboard edges of the heads were cut away to permit nestling the spark plugs as close as possible to the bore centers for quick, complete combustion. The W engine’s pistons also had V-shaped crowns. As a piston stroked upward on compression, the fuel-air mixture was squished across the cylinder toward the spark plug. This stirring effect enhanced fuel-air mixing upon ignition and accelerated flame motion throughout the wedge-shaped chamber. Invigorating combustion in this manner raised power and torque, improved fuel economy, and also smoothed the idle.

Such engineering tricks were necessary in an age before widespread fuel injection, and before modern tools were developed such as computer simulation of combustion flow, which today allows engineers to better understand what happens to fuel and air in the milliseconds before and after ignition. Pent-roof pistons and wedge-shaped combustion chambers are today rustic relics of an earlier era of engine development.

As was Cole’s philosophy with the small-block, the W’s cylinder bores were spaced 4.84 inches apart (versus 4.40 inches for the small-block) to give this engine ample piston displacement and room for growth. Starting with a bore of 4.125 inches and a stroke of 3.25 inches, for 348 cubic inches, the big-block would grow through the years, eventually topping out at 632 cubic inches.

We say 348, but the 1958 birth displacement was actually 347.47 cubic inches. Chevy rounded up because Pontiac already had a different 347 V-8. The use of cast iron for the heads and block yielded a base engine weight of 685 pounds in 1958 (versus 550 pounds for the small-block) but subsequent aluminum dieting dropped the big-block’s assembled mass below 600 pounds.

Stamped-steel rocker arms pivoting on balls attached to the head via screwed-in studs were similar to the small-block’s cost-saving innovations. But the small-block’s valves were arrayed in neat, straight lines, whereas the big-block’s valves zigzagged the length of the head to shorten the intake and exhaust ports for better breathing. The tubular pushrods carrying pressurized lubricating oil from the lifters to the rocker arms and valve stems were also inherited from the small-block.

Chevy’s new Turbo-Thrust 348 V-8 was rated at 250 horsepower when equipped with a four-barrel carburetor, and 280 horsepower in Super Turbo-Thrust form (with no turbo in sight but three two-barrel carbs on top). A high-compression, solid-lifter version was rated at 315. It should be noted that stated output ratings were gross figures, meaning without all the equipment necessary to run and plumb the engine. They were thus somewhat inflated until standardized—and more realistic—net industry measurements arrived in 1972. By 1961, the top 348 used a hotter solid-lifter camshaft to produce 350 horses. Chevy also offered a 409-cubic-inch, bored and stroked version for the 1961 Impala SS, with a forged-steel crankshaft, twin four-barrel carbs, and a 409-hp rating, prompting The Beach Boys to extol the virtues of Detroit’s hottest street racer. In 1965, this engine topped out at 425 advertised horses thanks to higher compression and more aggressive valve timing.

Drag and oval racers fared better. Chevy’s gift to them was the Regular Production Option (though not actually that regular) Z11, consisting of a 427-cubic-inch V-8 with cowl induction (for cooler, denser air), a two-piece intake manifold with two four-barrel carburetors, 13.5:1 compression, and a few aluminum body parts. An alleged 50 such cars were built, plus a few spare engines sold over the parts counter. Z11 Chevys are all but priceless today.

To transition to the second generation of its big-block V-8, Chevrolet supplied southern racers with what is now known as the Mark II Mystery Motor, not because GM had a ban on racing, but because Chevy was striving to hide its latest technology from the competition. Here, the weird block and head design had evolved into a more conventional arrangement. The side edges of the cylinder heads were straightened to accommodate spark plugs angled toward the bore centers. The displacement was limited to 427 cubic inches, to comply with NHRA and NASCAR rules. Combining a 4.312-inch bore dimension from the 409 with a stroke lengthened to 3.65 inches yielded just under 427 cubic inches. For enhanced breathing, all valves were angled toward the center of the bore, a configuration soon nicknamed “porcupine.” Four-bolt main bearing supports were added to improve durability.

Billy Krause earned a third-place finish at the 1963 Daytona 24-hour race driving a Corvette with the Mark II V-8 prepared by Mickey Thompson. The following week, five Chevy Impalas powered by this engine qualified for NASCAR’s Daytona 500. Due to reliability issues, the best finish was Johnny Rutherford’s ninth overall.

When an attempt to recycle a Packard V-8 for Chevy’s use failed, GM skipped the Mark III designation to launch its Mark IV big-block in 1965. Porcupine heads and four-bolt mains made the leap from the Mark II V-8. The dry weight went up 10 or so pounds, in part due to meatier main-bearing bulkheads.

The Mark IVs for 1965 Corvettes and Chevelles displaced 396 cubic inches and produced 375 horsepower with 415 lb-ft of torque. With solid lifters, gross output leaped to 425 horsepower. A slightly larger bore yielded 402 cubic inches, though Chevrolet stuck by the 396 label to avoid marketplace confusion. Camaros, Novas, Monte Carlos, full-size Chevys, and pickups all thrived with these engines equipped with a variety of compression ratios and carburetors to deliver 265–375 horsepower.

Marching smartly along, a 427 big-block debuted in 1966 for Corvettes and full-size Chevys at the height of the muscle car wars. During the next five model years, this Mark IV flexed major muscles in a variety of carburetion, camshaft, and compression-ratio configurations to deliver up to 435 horsepower.

To honor GM’s ban on direct motorsports participation, resourceful engineers crafted special parts on the sly, quietly slipping them to worthy racers. To enhance the 427 Mark IV’s performance, a special L88 package was developed that offered new aluminum cylinder heads saving 75 pounds and a long list of support parts, including a four-bolt main bearing block carrying a forged crankshaft, forged pistons tied to shot-peened connecting rods, triple valve springs, an aluminum intake manifold topped with a monster Holley carburetor, and an aluminum water pump. Roger Penske campaigned a 1966 Corvette powered by an L88 engine in the 24 Hours of Daytona; in spite of a heavy crash, he won his class and finished 12th overall. The following year at Le Mans, an L88 Corvette topped 170 mph on the Mulsanne Straight before dropping out with a broken crankshaft.

Ex-racer Zora Arkus-Duntov, the Corvette’s patron saint, then released what was billed as an “off-road” engine for Corvettes. Only 216 were sold in the 1967–69 model years and survivors are the most valuable Corvettes money can buy. One brought $3.85 million at a 2014 Barrett-Jackson auction. Mandatory equipment included transistor ignition, heavy-duty suspension and brakes, and a limited-slip differential. To discourage road use, heater and defroster equipment were not included. The L88’s 430-hp rating was creatively 5 horses fewer than the mainstream 427 engine equipped with three two-barrel carburetors.

In support of the Can-Am competition raging at this time, GM collaborated with Reynolds Aluminum to convert the big-block V-8 to a cast-aluminum design with iron liners fitted for durability. This move yielded an assembled weight of approximately 575 pounds, only a few more than an iron small-block. To prove this ZL1 V-8 was a production configuration, two Corvettes and 69 Camaros rolled down 1969 model year assembly lines with them. At $4718.35, the ZL1 option nearly doubled the price of a Corvette. Advertised output was a grossly understated 430 horsepower. Independent testers found that adding headers upped that figure by nearly 100.

In response to ever-tightening emissions regulations, Ford and Chrysler both pulled the plugs on their NASCAR programs and their big high-performance V-8s in 1970, leaving GM as the sole maker of a NASCAR-worthy engine. Stretching the stroke to an even 4 inches for 1970 yielded (an honest) 454 cubic inches. This big-block delivered a meaty 500 lb-ft of torque in full-size Chevys, Chevelles, Monte Carlos, El Caminos, Corvettes, and GMC Sprints. The top power rating was 450 horsepower at 5600 rpm with a single four-barrel Holley carburetor. When net output ratings and lead-free gasoline arrived in 1972, the same 454 Corvette V-8 topped out at a meager-sounding 270 horsepower. Three years later, yielding to regulations and oil crises, big-blocks were broomed from the Corvette’s options list.

Updates included with the 1991 Gen V big-block were four-bolt main bearing caps, a single-piece rear crankshaft seal, and attractive cast-aluminum valve covers. Provisions for a cam-driven fuel pump and valve-lash adjustment were deleted. The 454 version continued on for five more years, christened Vortec 7400 in 1996 in celebration of GM’s discovery of the metric system.

A 502 big-block also popped up in GM’s 1991 Performance Parts catalog. These crate engines, offering up to 600 horsepower for street and marine use, included throttle-body fuel injection and the electronic equipment needed to control it. A 572 version provided 620–720 horsepower depending on the compression ratio selected.

In 1996, a new sixth-generation Vortec 7400 displacing 454 cubic inches arrived exclusively for truck use. Its claims to fame included roller hydraulic lifters and multi-port electronic fuel injection yielding up to 290 horsepower.

Acknowledging there was more where that engine came from, GM replaced the 7400 with its Gen VII Vortec 8100 in 2001. In addition to a longer 4.37-inch stroke, this big-block boasted a revised firing order to improve smoothness, longer connecting rods, and metric fasteners throughout. In 2009, the last Gen VII big-block left GM’s Tonawanda, New York, engine plant, which currently manufactures the Corvette’s LT2 small-block V-8.

Suggesting that Chevy’s big-block may survive to consume the very last drop of petroleum, the performance aftermarket still holds this V-8 dear. Complete engines can be assembled devoid of GM components, and aluminum blocks and heads are readily available. GM recently set its best and brightest experts to work designing a fresh edition to be sold as a crate engine. The result revealed at last year’s SEMA Show is the ZZ632 10.4-liter V-8 that delivers a stunning 1004 horsepower at 6600 rpm and 876 lb-ft of torque at 5600 rpm on 93-octane gasoline. The price: $37,758.

Electrification will eventually send the Chevy big-block and fellow CO2-spewing engines to the boneyard. But until then, the Rat in all its many forms will be revered as a superb means of converting gasoline and air into pure speed.

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Pretty pretty please do an article like this on the Ford FE engines (428 CJ is my favorite for some reason). This article made my Thanksgiving.

Great article, Don! As basically a life-long Chevy rodder, I am almost ashamed to say that I’ve only ever owned 2 Rats. And both were relatively stock 396s. I’ve always wanted to build a 409, but strangely have never done it. How can I claim to be a Chevy Guy when I’ve spent 98% of my time running SBCs? I’m like a self-professed “Ford Man” who’s never had a Flattie! Santa, if you’re reading this, please bring me a BBC (W or MKIV, either is fine – I’m not picky)! 😋

Well, I have the Flattie, if you want to try your hand at that!

Excellent and informative!

No mention of the crate LS7 Code XCH Big Block Chevy engine with a 12.25 : 1 Compression !

The running changes in Porsche’s M28 – the V8 that powered the 928 – would be fascinating to read about as part of this series.

I have read a lot about Packard but never heard about a recycle of the only two year run of the Packard V-8s. Please tell more about this. Is a very hidden bit of history.

Uhmmmm….SBC has been built for 70+ years?

The only thing that the LS has in common with the old school SBC is the bore spacing.

Otherwise it is a completely new and different design.

I agree, bore spacing is the only carry-over from the original SBC to the LS series.

I keep seeing reference to the bore spacing like the SBC and the LS are the same.

That’s like saying all 4″ bore motors are the same

No, the rod journals (and bearings) are the same. And the roller lifters.

WOW! What a great article!

A coupla things. It is my understanding that the W engines got their designation from the shape of the valve covers. Secondly, the porcupine designation came from the various angles of the valve stems, not unlike the quills of a porcupine. Because the porcupine and rat are both rodents, the big block engine came to be known as rat motors. The mouse designation for the small block followed the rat designation for the big block, not the other way around.

I didn’t know that was the origin of the “rat” nickname, but had also heard the “mouse” nickname followed the “rat” moniker.

I like these engine “histories”. Please keep them coming.

This is a great article for a lover of Big Block Chevrolets for 57 years like me.

Long live the ZZ632!!

The LS engine is better than everything EXCEPT a BBC with a good set of aluminum heads. Nothing beats a N/A BBC for torque on the street. I’ve owned and built many, including a 454+.060 for my current rat rod project. Enough torque to rotate the earth🙂

The first photo caption is incorrect. The pictured engine is an LS5, not an LS6.

It says 450 HP, why do you say it’s a LS5?

Two big giveaways, the cast iron intake manifold and the factory air conditioner

Solid lifter big blocks never came with factory a/c

It has an aluminum dual plane intake and no A/C! What photo did you get??

Orange Paint on the exhaust manifolds ? How cheezy is that ?

I know we’re talking Rats….. But, C’mon Guys, Source better pix !!!

I am an amateur hobbyist/builder/restorer , and that would never happen on my builds.

PS. there were only 201 396 Malibu’s for ’65 (Z16) Why not mention the Thousands of Impalas ?

No mention of the ’69 Stingray with 3 deuce, 427, 435hp???

Don, in your recent article in Hagerty magazine, Nov-Dec 2022, A Rat’s Life: Chevy big-block V-8s, you reference “When an attempt to recycle a Packard V-8 for Chevy’s use failed, GM skipped the Mark III designation to launch it’s Mark IV big-block in 1965.

I am writing this comment for my friend Charles Leindecker who is insured through Hagerty. In all the years owning/ racing several 409s, we have never read anything concerning Packard OHV V-8 design and possible use by Chevrolet.

Where could we follow up and read further as it has peaked our interests?

As an aside interest,I stumbled onto an article in Hemmings magazine,” Packard Powerhouse”, by Thomas A. Demauro. I found it extremely interesting for it’s 374 and 352 OHVs. I never knew! But I can understand Chevy’s interest at that time. Thank you for your time and help! John Schlager

Don, in your recent article in Hagerty magazine, Nov-Dec 2022, A Rat’s Life: Chevy big-block V-8s, you reference “When an attempt to recycle a Packard V-8 for Chevy’s use failed, GM skipped the Mark III designation to launch it’s Mark IV big-block in 1965.

I am writing this comment for my friend Charles Leindecker who is insured through Hagerty. In all the years owning/ racing several 409s, we have never read anything concerning Packard OHV V-8 design and possible use by Chevrolet.

Where could we follow up and read further as it has peaked our interests?

As an aside interest,I stumbled onto an article in Hemmings magazine,” Packard Powerhouse”, by Thomas A. Demauro. I found it extremely interesting for it’s 374 and 352 OHVs. I never knew! But I can understand Chevy’s interest at that time. Thank you for your time and help! John Schlager

No, the rod journals (and bearings) are the same. And the roller lifters.