Welcome to Breezewood, America’s literal tourist trap

Shelly passed a can of cold beer and a plate of French fries over the antique bar top. A waitress in her middle-age, she spoke matter-of-factly, barely looking up from her tasks as she answered my questions. “The reporter in here before you called this the ‘Rest Stop of America.’ Most people just take a sh**, fill up, and leave.”

I chewed on the fries, and on the thought that someone was here before me, doing the same exact thing that I was doing. Working over the same group of locals for insight into this odd little place. For Shelly, it was an unremarkable rehash. Routine is what makes Breezewood go ’round.

Only 178 people live in Breezewood, a south-central Pennsylvania plot that lies just east of the Allegheny Mountains. There is no city hall nor elected officials, with locals leaning on larger Bedford County for governance. None of that is unique for an unincorporated community in this country. Breezewood is, however, a fascinating anomaly born specifically of America’s highway system—a colorful, fluorescent-lit monument designed to be visited on wheels, more waypoint than destination.

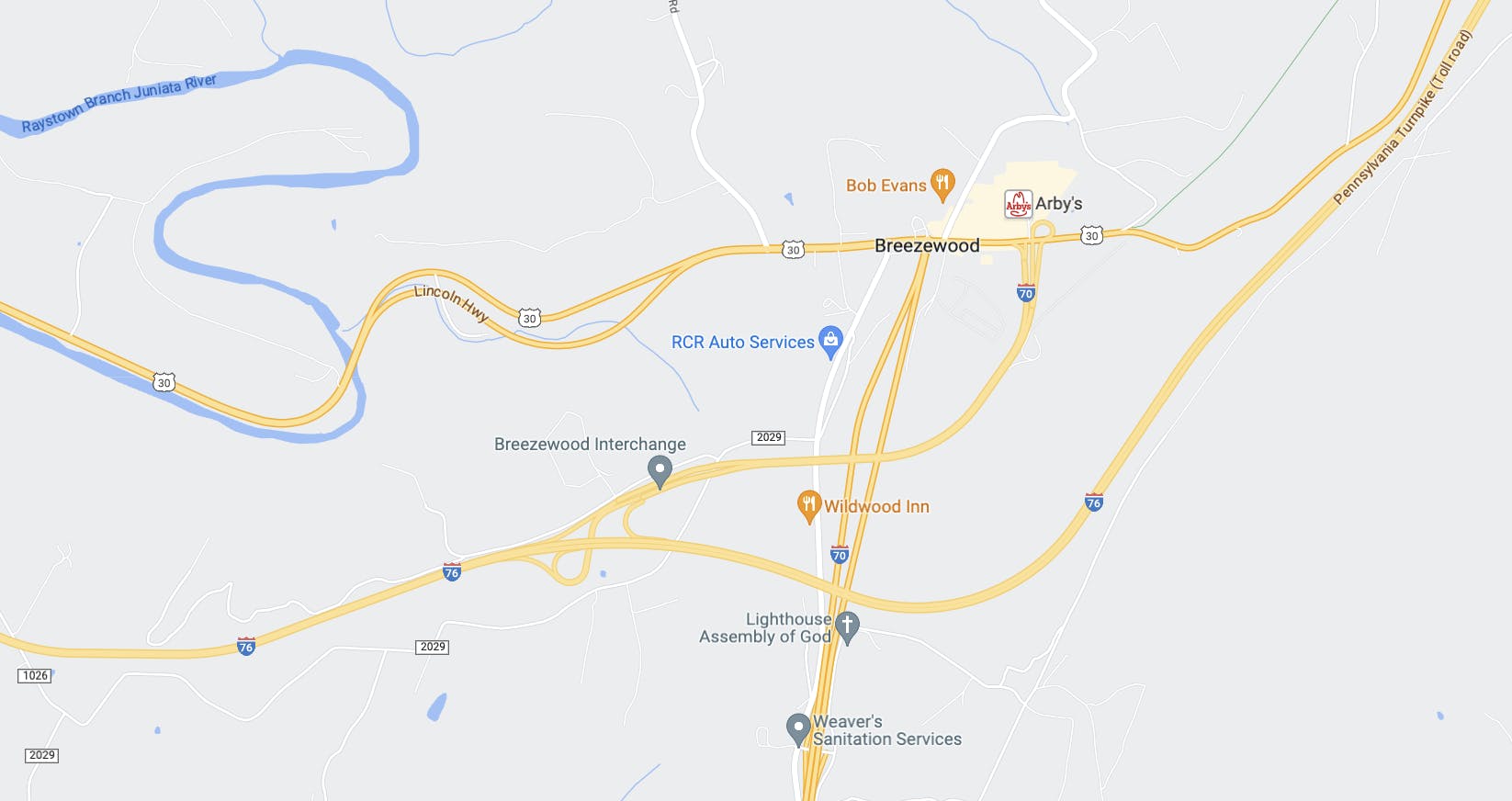

From the main drag, U.S. Route 30, it’s two hours to Pittsburgh or three to Philly. Also known as the Lincoln Highway, this route dates back to 1913, part of the first transcontinental highway designed specifically for automobile travel. The road follows the path of a valley over which the two-lane Pennsylvania Turnpike sweeps east-to-west. Interstate 70, another two-lane freeway, ushers traffic north-south to and from the Maryland border.

Travelers looking to hop from I-70 to the Turnpike, I-76, are offered no convenient merge or seamless cloverleaf. Rather, they must come to a screeching halt and weather the quarter-mile stretch of traffic signals, gas stations, convenience stores, and fast-food restaurants—aka Breezewood—before the transition is complete. The reason for this is an entanglement of arcane red tape, relating to the cost of a proper interchange compared with qualifying for federal funding to forgo one. The upshot, however, is fascinating: In 2019, Bloomberg reported that 3.5 million passenger vehicles and 1.5 million trucks roll through this commercial bottleneck in a given year.

Every travel stop is open 24 hours, 7 days a week. Breezewood does not sleep.

***

Prior to my arrival, I read no fewer than three full-length feature articles on the town, from outlets like The Wall Street Journal to the New York Times. What’s the obsession? For one, the town is a pressure cooker of commercial Americana seemingly airdropped in rural Pennsylvania. Breezewood’s slow decline has also come to exemplify, for some, what’s wrong with fickle corporate culture and ruthless capitalism squashing local businesses. In 1991, Business Week called it “a polyp on the nation’s interstate highway system.” The town has even become the punchline for a smattering of internet memes.

No matter how you slice it, Breezewood is a spectacle. Fine art photographer Edward Burtynsky snapped a shot of its main drag in 2008. A print of the photo sold at a 2017 Sotheby’s fine art auction for $43,750.

In the 15 years since Burtynsky’s shot, Breezewood’s only drastic changes are the varying fast food signage and a new, squeaky-clean Sheetz gas station. The layout remains the same: The motorist logjam occurs in a valley, its low point a four-way stop between I-70 and U.S. 30. It’s the gladiator pit for elbows-out motorists—a dizzying array of green signs, white arrows, and orange barrels. The congestion is difficult to appreciate until you take 30 out of town and look over your shoulder into the stew. From this elevated vantage point, particularly at night, the town is a magnificent canvas of lights and logos. It looks simpler from this perspective, too. Traffic engineers’ fingerprints suddenly seem comprehensible, from stoplight bypass ramps to a four-lane megastrip for westbound traffic.

Breezewood is a “traveler’s oasis” reflecting the state of American car culture, its siren song a fugue of gasoline fumes and roller hot dogs. Heavy-hauling semi-truck drivers clash with business travelers, vacationers, and everyone in between. The chirp of air brakes meets car horn blasts. This strip of I-70 is one of the only segments of American interstate with a stop light, so stop-and-go traffic is a fixture. Even if everyone is paying attention and every truck driver double-clutches to perfection, the section still produces backups. Gridlock is a guarantee during peak hours, so its severity is the only meaningful variable. On a holiday weekend, like over Memorial Day? Well, if you’re gonna sit still, you might as well eat a Beef ‘N Cheddar.

Amid my dirt-track race-chasing adventures all over the Midwest and Northeast, I’ve driven this stretch of turnpike plenty of times. The toll road connects the Midwest to some of the nation’s most historic circle tracks. Eric Weiner, the executive editor of this website and a Pennsylvania native, has too. We were talking road trips one day when Weiner pitched that I stay in the town and report on what I found. Rather than a pit stop, I’d spend 36 hours in Breezewood—longer than most people might spend cumulatively in their entire life.

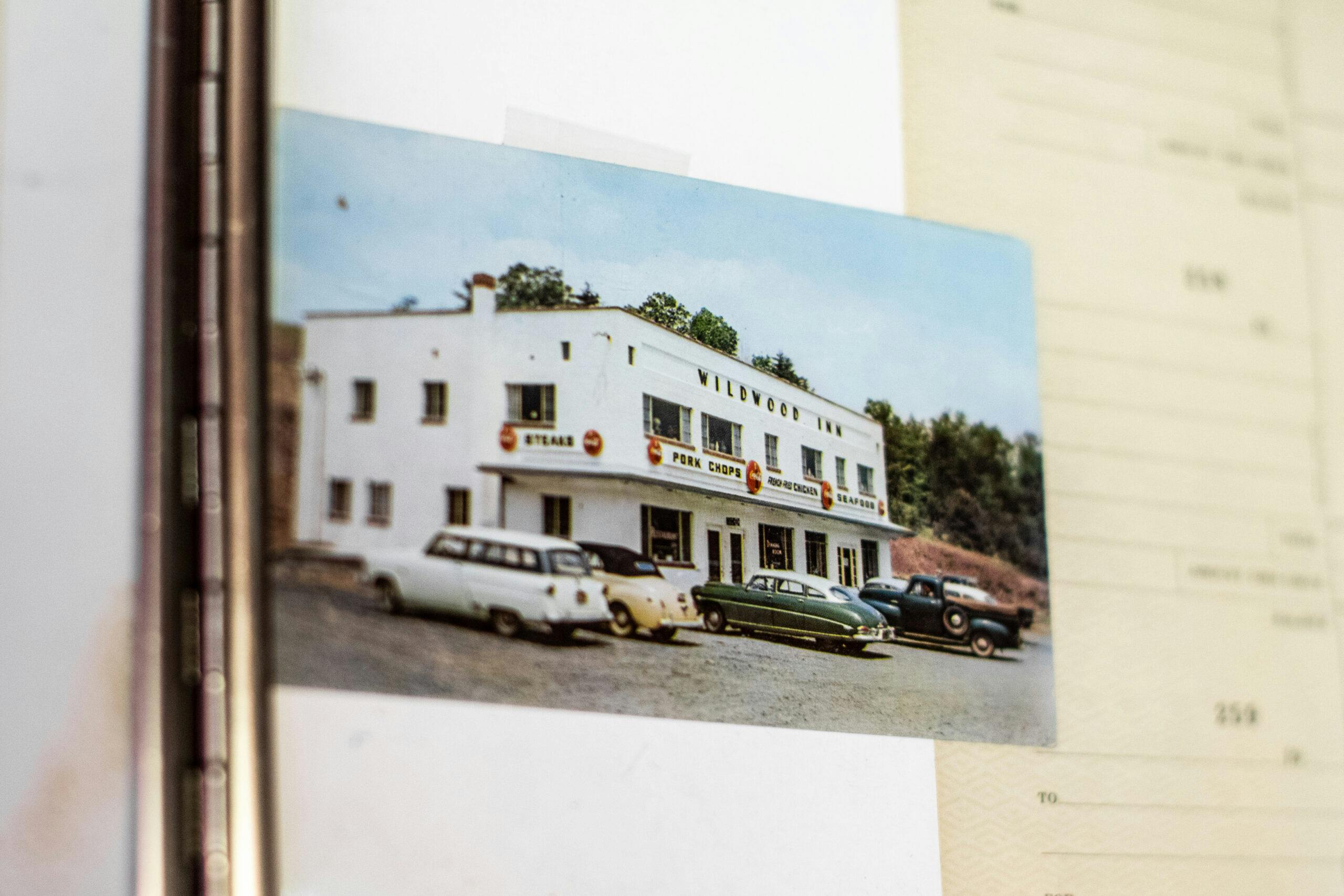

Less than a mile from Breezewood’s main drag, I sat on a stool at the Wildwood Inn, sipping the beer Shelly served up. The two-story hotel has outlived most of the other businesses in Breezewood. In 1955, Walter and Clara Price opened the restaurant. Traveling families turned off the Pennsylvania Turnpike for a warm meal, or to view its “world famous” collection of antique spoons and plates.

Back then, Breezewood was known as the “Town of Motels.” Present day, there are only a few options for a clean overnight stay. The Wildwood Inn no longer offers rooms. “I remember when the Ramada was nice, with chandeliers and a swimming pool,” said Shelly. “I worked there.” My haven was the Holiday Inn Express, a four-story box hotel wedged between the area’s busiest gas pumps: TA and Sheetz.

***

At the town’s peak, according to one local, Breezewood could sleep nearly 10,000 people. Handsome hotels like the Penn Aire, built in 1955, welcomed travelers with its light-up-script sign and ornate front entrance. The Breeze Manor, constructed several years later, was the first inn with a swimming pool. Whether you lived on the East Coast and were headed west or lived in the Midwest and were driving east, most vacationing families couldn’t get further than Breezewood in a day’s drive.

Though these mid-century hotels were new to the region, the promise of transit and hospitality was not. “You go back far enough, there was no Breezewood,” longtime local Forrest Lucas told me.

What is today Bedford County has been a travel hub since the first trading post in 1750, built on existing Native American trails. A couple miles to the east of where I was nibbling on fries sat Ray’s Hill. In 1836, shopkeeper John Nycum established the Ray’s Hill post office—reportedly the smallest in the United States, measuring six by eight feet—and served as its longtime postmaster. Ray’s Hill soon became known as Nycumtown. (You call the shots, it seems, when you control the means and the mail.)

Next to Ray’s Hill sat the town of White Hall and its 22-room inn, which served as a stagecoach stop for for westbound travelers leaving Philadelphia. Locals of White Hall and Ray’s Hill dubbed the valley between their towns “Breezewood.”

In the early 1900s, Breezewood became a stop on the Lincoln Highway. A young Dwight Eisenhower and his comrades rambled past in their Army convoy in 1919 amid a 62-day journey, known then as the Trans-Continental Motor Truck Trip. Frequent reports on the state of America’s roads—as well as the effectiveness of nascent off-road motor vehicles—were sent back to Washington.

A decade later, Breezewood was on the eve of its first big break. To improve travel through the area, namely through the Alleghenies and the Appalachian Mountains, the federal government began to build the Pennsylvania Turnpike using seven tunnels from a failed 19th century railroad project. Approximately 15,000 workers sourced from 55 different construction companies laid pavement at a rate of about 3.5 miles per day. The Turnpike, also known as America’s first expressway, was finished in 1940. Breezewood was enshrined as Exit 6, and business boomed.

In 1941, Merle Snyder established Gateway Motel and Restaurant for turnpike goers. Gateway Travel Plaza, as it is now called, is one of the only businesses remaining from Breezewood’s golden age. Rather than the original bed and breakfast with a second-floor bunkhouse, though, it looks today largely like any other highway stopover—a TA truck stop, Exxon fuel station, showers, a Dunkin’, and an Arby’s.

***

Interstate 70 was built in 1960, and the aforementioned strange set of clauses pertaining to the funding of the highway would ultimately change the fate of every soul who worked in, lived in, or passed through Breezewood.

Section 113b of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 mandates that motorists must have the choice whether to enter onto a toll road. Under Section 113c, the state and the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission (PTC) could use federal funds to build an interchange between the new I-70 and the Turnpike, but both parties would have to agree to stop collecting tolls when the funding ceased.

Naturally, toll authorities were unwilling to use their own revenue for an interchange that would give travelers the option to leave toll roads. The PTC was also expecting a decrease in dollars when construction on I-80—which also runs east-west though Pennsylvania—was finished.

State highway officials took matters into their owns hands. Their solution: Extend I-70 north, past the east-west Turnpike, and connect it with U.S. 30, the Lincoln Highway. There, in Breezewood, motorists would have the option (required to ensure federal funding) to stay on U.S. 30 or pay the Turnpike toll.

Thus, Breezewood transformed from Pennsylvania Turnpike exit to literal tourist trap. The quarter-mile strip of asphalt held a captive audience for food, fuel, and lodging. Businesses got in line for a piece of the pie. By 1969, there were a reported 19 motels and 10 gas stations in town. Travelers pumped more than a million total gallons into their cars per day.

***

Breezewood looks a lot different now than in its heyday. A strip of chain stores overtook the mom-and-pop shops. Corporate tenants also appear to be struggling, however. On U.S. 30, for a couple of miles in each direction, there are just as many abandoned buildings and overgrown parking lots as there are functioning businesses.

The ethos of commercialism-gone-amok that some people project on Breezewood only touches on the community’s present predicament. With the decline of available lodging options in town, the entire economic system relies on less-than-12-hour tourism and is handcuffed to the interchange. Everything actual locals might spend on, from groceries to auto parts stores, are located in neighboring towns.

Breezewood businesses rely heavily on big rig trucking and truckers. Two large truck stops—a TA and a Flying J—are positioned on the east and west sides of the valley. There, long-haul drivers refuel, repair, and rest. This lifestyle forms the basis of Breezewood’s most communal activity, with drivers exchanging “howdy-dos” and general small talk around the lot.

Breezewood’s workers and businesses there aren’t in control of their prosperity or demise as much as they are subject to shifting traffic patterns. The paving of a new road or the widening of another could shuffle people away from Breezewood’s nuanced interchange.

Take Interstate 68, for example. The east-west highway runs about 20 miles south of U.S. 30 and was completed in 1991. Suddenly, those traveling from Washington or Baltimore to the Midwest could avoid the PA Turnpike—and Breezewood—completely by taking 68 through northern Maryland. The town’s Howard Johnson closed the same year I-68 was finished.

Plenty of other external factors have changed the travel landscape since Breezewood’s mid-century boom. Airfare, for instance, has become a whole lot more affordable. And even the most affordable new cars are capable, comfortable highway cruisers with relatively excellent fuel efficiency. The once-essential need to stop, rest, and refuel just isn’t there anymore.

At one point during my visit, I drove up the hill on the west side of Breezewood to attempt my own version of Burtynsky’s five-figure-fetching shot. With my camera on a tripod, balancing precariously on the edge of my truck bed, I could see it all through the viewfinder. Plastic and metal signs that once advertised promising businesses had been painted over, smashed, or covered with the banner of some new venture. Some businesses were dark, others completely abandoned. Breezewood’s fall from its peak has been slow and steady, rather than sudden.

“There’s just not enough traffic to maintain all the businesses,” says Forrest Lucas, whose family opened the Traveler’s Rest Hotel in 1968. “Hotels became low-rent apartments. This brought in drug problems.”

Businesses either die or adapt, and Crawford’s Gift Shop has done the latter. The Crawford Family moved their taxidermy business from Everett, Pennsylvania, to Breezewood in 1957. Travelers—and local schools—shuffled in to view exotic mounts in the building on the east side of the strip. Then, in the 1980s, the family renamed their store Crawford’s Museum (and Gifts) and sold souvenirs alongside their preserved critters.

When the Pittsburgh Steelers football team started winning in the 2000s, Crawford’s began to sell black-and-yellow regalia to fans. Football accoutrement soon replaced the more familiar souvenirs, though the popular animal mounts remained. Now, Crawford’s is known as “Your Black and Gold Headquarters,” and John Crawford V runs the show. The business seems to be doing well enough, and part of that has been diversifying income streams beyond foot traffic. Much of John V’s merch is now sold online. “We sent a Steelers jacket to Israel,” he said before quickly resuming inventory checks.

Most of Breezewood’s employees live outside of town, in Bedford County and the surrounding valleys. They list off cities like Everett or Bedford or just stick a finger in the air and say “up on a hill over there.” By its working class, Breezewood is treated more like a factory or warehouse than a proper town. Clock in, clock out. Most tell me something to the effect of, “Breezewood isn’t a city. It’s a stop.”

Emphasis on the stop. Traffic is indeed a nightmare in Breezewood, but nobody is doing anything about it. Some type of bypass to divert traffic would require township or county levels of government approval, and money, but Breezewood can hardly sustain itself in current conditions. Not to mention that any bypass would, in effect, completely obviate Breezewood’s entire reason for existence. Everyone is soldiering on, but for how long, who knows?

On my way out of town, I took a detour to investigate the town’s abandoned highway tunnels, closed after the Turnpike’s four lanes were rerouted to avoid the one-lane underground bottleneck. The mountain passes are now a cult attraction for trail-hungry hikers and bikers. The stretch of road, pockmarked and overgrown with vegetation, has been used for feature films, most notably for 2009’s The Road, based on Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic novel. Nature abhors a vacuum.

I prefer to think of Breezewood as a town in perpetual flux. Before the government turned it into an artificial choke point, before Breezewood even officially existed, this valley was a throughway for travelers. Once a pit stop for the tired or hungry, its sheer novelty and history have also ensnared the curious, like me. Maybe some savvy investor will swoop in and turn abandoned businesses into a long rows of EV chargers; there’s already a new bank of Tesla chargers in the Sheetz parking lot.

Or maybe, if more businesses shutter, some areas could be turned into a trail system or nature preserve for eco-tourism. However Breezewood evolves, or whatever ultimately takes its place, the right vision could once again turn it into someplace people want not just to stop, but to stay awhile.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

When I was going to college in the 70’s in the MidWest Breezewood was a regular stop coming and going; it became a progress marker of sorts. When I went to orientation I tok a Greyhound and we stopped there to eat, if I recall correctly.

It looks like so many off the highway small towns with a dozen motels/hotels. The trails you found look very interesting to me.

In 1969 my wife and I on our honeymoon stayed in Breezewood while on our way to Colonial Williamsburg from Michigan. I remember sitting on the edge of our bed looking in their phone book, which was no more than 1/2″ thick, and reading “In case of emergencies call xxx-xxxx, if no answer call zzz-zzzz”!

The one point you missed in the article is the political aspect that guaranteed that the bottleneck would continue. All tied up in the late State Representative Bud Schuster. The big wheel on some House transportation committee. Back in the 70’s (or was it the early 80’s, I’m writing this from memory) the backup from I-70 to the PA Turnpike thru town had gotten so bad that it was seriously considered making the connection between the two roads direct with a small feeder exit to allow access to US30 and the town.

Of course this would have been disastrous to the businesses in town, as fully 95%+ of travelers would have happily avoided going into town. Bud Schuster immediately jumped into the fray (at the request of the dozen or so people who actually controlled the unincorporated town – there’s a reason it’s always been unincorporated) coming up with legislation and funding to add additional lanes to the main drag, as well as writing something into the paperwork expressly stopping any kind of construction that could possibly result in a bypass. Which is a shame, because the space is there, and it would have been very easy to implement. The local papers back in the day were bringing this point up readily and often.

Representatives Bud Schuster (Altoona) and Jack Murtha (Johnstown) became the ‘poster children’ of government pork-barreling in the early 2000’s, just for behavior of this type. As a former resident of Johnstown, now living outside of Richmond, I was watching this with great interest and very divided loyalties: One one hand I was enraged at the government wastage, on the other hand as a former resident of the area I fully realized that said ‘government wastage’ was all that was keeping this area from becoming a complete cesspool of poverty.

Breezewood wasn’t Bud Schuster’s only monument. Take a look on the map at I-99, going northbound out of Bedford and ending . . . . . . well, where exactly? It was nothing more than US220 turned into a four lane limited access highway that was supposed to connect the Turnpike to I-80. It never got finished while I still lived there, and is a complete misuse of the Interstate designation. Given the original intent, I-99 is supposed to be running north/south east of I-95. Which would be somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean off the eastern seaboard.

One correction to my reply: Bud Schuster was a member of the US House of Representatives, not the Pennsylvania State House. I didn’t realize I’d be making it look like the latter when I wrote it.

The comment “…the federal government began to build the Pennsylvania Turnpike…” is incorrect. The Turnpike was a homegrown Pennsylvania project. Planning started in the mid 1930’s to develop an “All weather highway” that initially connected the towns of Carlisle and Irwin. (Extensions to the east and west came in the 1950’s).

The intention was to supplant the treacherous US Route 30 and its steep, twisting course over several mountains. Hence the creation of its original seven tunnels – early on, the Turnpike was commonly known as the “Tunnel Highway”.

The Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission (PTC) was created to administer the planning, construction and funding of the highway. It issued bonds for this purpose. The debt was self liquidating through the imposition of tolls.

The Federal Government’s funding of highways began with the Interstate and defense highway act of 1956, championed by the Eisenhower administration. The concept grew out of Ike’s experiences on the military’s 1919 transcontinental motor truck trip. The word “Defense” was included in the act’s original title in order to gain political support for its passage – WWII had ended just over ten years earlier.

In 1964, the Turnpike received the designation of I-76 as part of the Interstate Highway System but remained under the control and funding of the PTC, as one of the requirements for accepting funding from the Federal Interstate Highway Act was a ban on tolls. This inclusion required that the highway be brought up to then current Interstate design standards. As a result, in the late 1960’s into the early 70’s, several of the single lane tunnels were closed and replaced by reconstructing the route to travel over the tops of the mountains.

The Turnpike today remains under the administration of the PTC as a toll highway. A reconstruction of all 17 travel plazas started in 2007. About half of the road itself has been rebuilt under the current Statewide Total Reconstruction Initiative, which will eventually widen it entirely to three lanes in each travel direction.

The PTC was fortunate in that the right-of-way for the highway was a roadbed for a failed railroad line that was never finished. However, most (if not all) of the tunnels had already been built prior to the railroad’s failure, so the hardest part of the highway construction was already completed.

Breezewood eh? Never knew that clusterf*** had a name…

I grew up 100 north of Breezewood. We had family in D.C. and I traveled thru the ‘City of Hotels’ often in the 60’s and 70’s. A stop at the Gateway for ‘refreshment’ was a ritual. In those days, I remember the place being highly regarded by my grandmother for their excellent homestyle meals. Later in life I lived in Frederick MD and would make the same trek back to my hometown in Indiana county PA at least once or more per month. These day’s living in Pittsburgh, I pass the waypoint once, maybe two times each year. I have witnessed first hand its rise and decline in my lifetime.

George “Syke” Paczolt and Bill Collins previous comments have provided accurate accounts of Breezewood’s legacy, imho. If you dig deep enough you will nearly always find money and politics at the root of any ‘clustercuss’. And while the intent for maintaining its existence may have had good reason, that being the economic benefits provided to an isolated area of Appalachia, its execution was far from one that would uplift the wellbeing of an otherwise deserving and hardworking community with meager prospects. About as successful as trickle-down economics from my viewpoint. We could also look to the vast highway system of West Virginia federally financed by the political shrewdness of the late senator Robert Byrd. Hundreds upon hundreds of millions spent on a 424-mile interstate network parts of which are referred to as ‘the Highway to Nowhere’. These are some best ‘driving’ roads I have ever experienced, by the way, having logged many miles in spirited fashion onboard both 4 and 2 wheeled vehicles .

While not directly affected by Breezewood’s history, I still feel somewhat connected. I grew up in a small coalmining town not too far away and it’s legacy is not all that different. Over the years I spent many more hours than I probably should have in a few of its bars listening closely as I shared beers and conversations with it local hosts. Good salt-of-the-earth types who felt and acted like extended family from my own hometown. As I see the story, it’s not about misappropriated funding, the monopolization of mom and pop economics, or even the automobile. What it is about is the people who make up the town. And their shared dream of a better future for their children built upon on their greatest asset. An honest day’s hard work.

With two 1980s assignments to DC, friends in Cleveland and family in Detroit, I got to see a fading version of the original Breezewood. By the time of a fall 2022 gas up there, it had pretty wel faded.

I read this article just a few weeks ago. I just went to Pittsburgh from Baltimore for the first time in my life and I passed through here. Of course, I recognized it.

This brings back memories. Usually a stop at Sheetz on the way from Pittsburgh to DC or Baltimore. I never thought the traffic was a big deal.

Interesting report. Been through Breezwood many times traveling from Delaware to my parent’s homes in Detroit. Always thought it odd the way I-70 just ends into a little town with a big traffic jam. The road in the town is under constant repair from the stress of all the heavy semi traffic crawling along. Bless you for spending 36 hours there. Don’t know if I’ve spent that much time there in my lifetime yet getting gas.

“Two-lane highway” may not mean what you think it does.

My Dad once remarked: ” There are two places you never want to drive through: Breezewood on Labor Day, and downtown Cairo…”