The true story of how I drove 800 miles in a car the size of a hat

Across the digital world, most published content is designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the depth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears.

Pour your beverage of choice and join us now for a story from our Great Reads project. Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: tips@hagerty.com

Things got weird. Or perhaps they started weird, and in some kind of dollhouse Stockholm madness, I simply could not tell the difference.

I was in the American South, for 800 miles and five days, in a 14-horse German three-wheeler the size of a hat.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A microcar.

There were chickens.

Last spring, I had dinner with Tennessee’s Jeff Lane. Jeff founded a car museum in Nashville. He is both a friend and a generally swell human. As I levered my nose into a bucket of gin and tonic, he mentioned a looming vacation. A week on the beautiful Natchez Trace Parkway, he said. A group of microcar owners was trekking the road’s length, Nashville to Natchez, Mississippi, for fun. Then they were doing that same drive in reverse.

In the postwar austerity of 1950s Europe, money was thin on the ground. Industry churned out bare-bones transport, small cars powered by repurposed motorbike engines. Most were quirky, loud, slow, and hot. Fast examples might crest 60 mph; others would not top 35 without falling off a cliff.

To know anything about microcars is to know that whipping one through modern traffic is like gunning a lawn tractor down the freeway while listening to a wood chipper eat forks.

Do not ask why, Diary, but I begged Jeff: Let me go with.

He took a swig of his drink. I could loan you a car, he said. Then he smiled the smile of a man who knows something you don’t.

***

We began in June, on a Monday, at The Lane Motor Museum.

The cast rolled in from all corners. Nine cars in total. Jeff and his partner, Christine O’Neill, arrived in their 1969 Fiat 500L. Florida’s Patty Schwarze, a retired pancake-house proprietor, brought her 1960 BMW 600. I met Gene Burshtein, a commercial realtor from Brooklyn, New York, as he unloaded his 1958 Vespa 400 from the bed of his Ram pickup. The difference in scale made the Vespa appear to be wearing the Ram like a boot.

“It fit,” Gene said, pleased.

Wayne Saunders, a retired car dealer from Oklahoma: 1970 Subaru Sambar pickup. Bob and Jennifer Lancaster, electrical contractors, North Carolina: 1973 Fiat 500. Herb de la Porte, a retired paramedic, Ohio: a 1973 Bond Bug three-wheeler. Herb’s wife, Sheila, brought a 1958 BMW Isetta. Larry Newberry, from Tennessee, once ran a microcar restoration shop with 12 employees; the 1958 Vespa he towed to Nashville is one of the 47 (!) Vespas he has restored.

Jeff Lane loaned me his 1956 Heinkel Kabine. This 14-horse road nugget, two front wheels and one rear, was the slowest machine in our caravan. Every car had teacup pistons. The Vespas, being two-stroke, drank oil with their fuel. The drivers had little in common save obvious joy at being temporarily outside anything like real life.

Not every machine present, Jeff noted, was a microcar in the traditional sense. The 750-cc Bond and the BMW 600, he said, eclipsed the unofficial 500-cc class displacement cap; the Fiats, he told me, were at that limit but too “normal.” Too fast and comfortable, apparently.

I asked if this dichotomy was important. Jeff shrugged—they were all funky and small, he said, so who cares?

The Bond Bug had a doorless fiberglass body, a solid rear axle, and a roof-windshield assembly that tilted up for easy ingress. That last part would have made more sense if the car had been designed with doors. “It’s super weird,” Herb said.

“The Sixties were a great time for drugs,” I said, squinting like Columbo.

“Let’s face it,” Herb said, brightening, “a fantastic time for drugs! All these cars came out of drugs! They’re all bright colors!” Then he started the Bug and revved it wildly in neutral, as if to emphasize something about drugs or fantastic times or, as the man said, Who Cares?

The ensuing week would bring mechanical failures large and small. Significant quantities of alcohol would be consumed in hotel lobbies. Every person I would meet would be a delight. At a Mississippi gas station, for reasons that felt important at the time, I would buy multiple rubber novelty chickens. Corny jokes would fly fast and loose, mostly regarding the strange thrill of long-distance travel powered by shot-glass pistons.

But that was later. In the meat of a Tennessee summer, in humidity thick enough to taste, our caravan clattered and ring-a-dinged out of Nashville. Five miles later, while baking next to the Heinkel’s barely insulated drivetrain, behind the car’s refrigerator-style door, behind windows that did not roll down, I was already slap-happy, drenched in sweat and deaf.

Probably heat stroke, I thought.

Spoiler: It wasn’t.

***

Who decides a transport machine must look like this?

Airplane engineers, apparently. Still, you get the sense even they weren’t convinced.

The Heinkel Fleugzeugwerke (“aircraft works”) found success building mail planes in the 1920s, then bombers for the Luftwaffe. Reparations after World War II made further airplane construction illegal, so the company turned instead to affordable scooters and microcars, to help postwar Germans get back on the road.

Some 6000 Kabines were sold from 1956 to 1958. Their buyers took home a machine not unlike a BMW Isetta, if an Isetta were 200 pounds lighter and shaped more like a mutant carp. Each ten-inch front wheel wore a hydraulic drum brake and independent suspension. The single rear drive wheel rode in an alloy swing arm that also carried a one-cylinder, 175-cc Heinkel scooter engine and a sequentially shifted four-speed gearbox.

Before we left town, Jeff Lane gave me a shakedown ride around the block.

“The ignition switch,” he offered, “is weird.”

“I never would have guessed,” I said.

Pushing the Heinkel’s key into its dash lock powered the car’s electrics; pushing it down from there engaged the starter. The engine idled with a pleasant little wocka-wocka, like a chainsaw at the bottom of a pool. The white plastic shift knob, no larger than a nickel, sat at driver’s left. Ignore the gearbox and its bag of false neutrals, the Heinkel would lose speed at full throttle on level ground. Sometimes it did that anyway.

The brakes were mostly useful for ensuring the car did not roll around in the wind at stoplights, which is not a joke. Opening the folding roof allowed in a modicum of air but also the blazing sun. Top speed varied with humidity and tire pressure, but opening the roof and the two triangular vent windows might drop VMax by 5 mph.

During that shakedown drive, as the Heinkel fought to hold 30 mph on a hill—Third gear! No, we’re slowing, back to fourth!—Jeff told me about driving this very car in a 1200-mile rally across Italy.

“We climbed a mountain,” he said. “First gear, wide open, for an hour.” Pause for emphasis. “An hour.”

What he didn’t mention: Later, they had to go down that mountain.

Gravity can move a Heinkel Kabine more quickly than the car’s engine. Over a week of travel, the pattern held: A feeling of immense freedom as you crested a hill and shifted to neutral. Rampant acceleration. Then some reminder of the existence of physics—a corner, a bump—followed by a sense of light concern welling up from the base of your spine and a genuine curiosity as to why you were, at that moment, on three ten-inch wheels, in a 100-inch-long German Barcalounger, trusting your life to a pair of brake drums comically ineffective and yet still capable of lifting the rear wheel.

Somewhere in the terrifying bliss of this descent, you would achieve the speed limit. A rate of travel you had lusted after while climbing the hill, except you were wrong.

“We see these cyclists pedaling up the mountain,” Lane said, “and we’re barely catching them. We finally pass, and then they suck in behind the Heinkel for a draft.”

This hopped-up-on-goofballs Rascal scooter went . . . 1200 miles?

“Stuff always breaks. Two hundred miles a day may not seem like a lot, but you might spend three hours by the side of the road. You end the day and—”

“It’s a lot?” I said.

“A lot.”

But he was smiling, see, when he said it.

***

Toward the end of the trip, at a lunch stop, we sat and talked. Around a long wooden table, over gallons of iced tea, the owners answered my questions:

Why microcars?

Herb de la Porte (Bond Bug): [Shrugs] I just like weird stuff?

Jennifer Lancaster (Fiat 500): I fell in love with a little blue Isetta. They multiplied!

Gene Burshtein (Vespa 400): Because I don’t need to compensate. [Group laughs]

Larry Newberry (Vespa 400): I couldn’t afford a whole car. [Group laughs]

No one owns just one micro. Patty has 15 of them. Why?

Patty Schwarze (BMW 600): They don’t stay running? [Group laughs]

Why travel long-distance in a scooter with a hat on it?

Patty: It is an amazing conduit, a wonderful way to meet people. People say that about all unusual cars, but here, you don’t get any of the jealousy or aggression. People are just happy to see you.

Sheila de la Porte (BMW Isetta): We want people to enjoy them—“I’ve only seen that on TV.” Now you can sit in it!

Patty: At car shows, we’re next to a muscle car, nobody looks at the muscle car. “How many people can you fit in there? Where’s the wind-up key?”

Gene: “Did you drive that here?” No, I put it in my pocket.

***

The Natchez Trace Parkway is managed by the National Park Service. Manicured pull-offs and tidy wooden signposts border a limited-access two-lane built along the path of an old Native American trail. The road covers 444 miles end to end, from rolling hills in the north to flat low country in the south. Dwarfed by a canopy of trees and passing motorcycles, our little caravan went end to end to end, Nashville-Natchez-Nashville, like a wagon train of Smurfs.

On the second afternoon, the group played musical chairs, swapping seats for giggles. I was told to try other cars. Who says no?

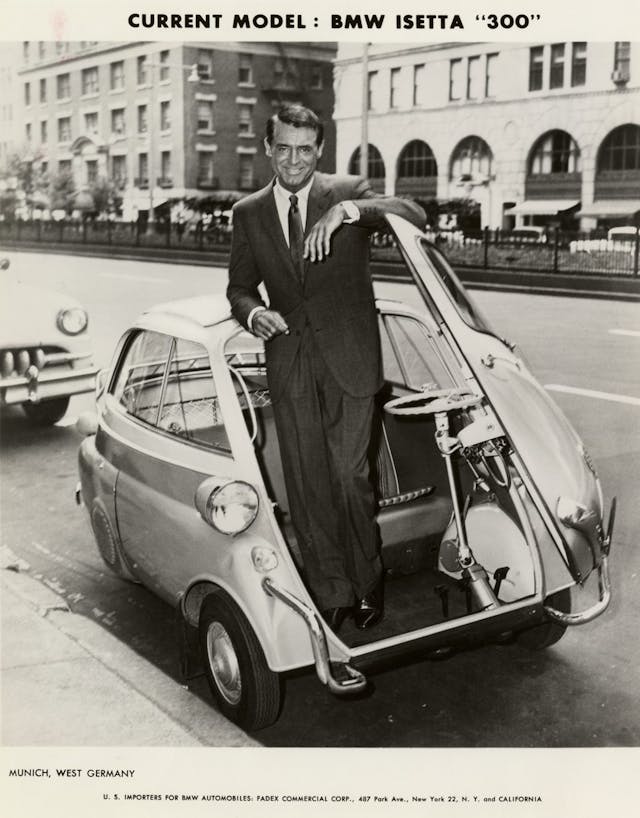

1958 BMW Isetta (300 cc): The Heinkel but more normal, with a smoother engine. Louder but slightly more stable at speed. (Isettas have two rear wheels, albeit in the middle of the car.)

1960 BMW 600 (600 cc): Like a stretched Isetta but more grown-up—four-wheel independent suspension, real torque, a back seat for two adults, a comfy interior. A small shipping container that wants to be your friend.

1973 Bond Bug (750 cc): Lightly menacing but oddly stable at speed. Also wonderfully fast. Seventy miles per hour was, to paraphrase The Hunt for Red October, possible, but not recommended.

1970 Subaru Sambar (360 cc): A chipper little groundskeeper’s truck with tissue-paper trim and a smooth two-stroke twin behind the rear wheels. Imagine a VW Transporter shrunk in the wash. My head touched the headliner and my knees hit the dash, which is nice, because I am five-foot-ten and I never get to say those words and if this life is not about novel experience then why leave home?

*

Commonality was limited. Build quality varied from “BIFL household appliance” to “hardware-store discount bin.” Chiefly, you could have sussed each car’s nationality with closed eyes. Chalk it up to the intersection of tiny footprint and hyper-low build cost: The more compromises an engineer must make, the more those compromises say about the engineer. And a microcar is compromise on the hoof.

Patty Schwarze, the BMW 600 owner: “You can tell from the owner’s manuals.” The French ones, she said, didn’t give much information, laissez-faire. (“I had a Panhard where every wire in the harness was brown.”) Predictably, Patty continued, the Italian books delivered only vague shrugs of detail, and the German ones were precise about everything.

“It’s in the Messerschmitt manual,” she said. “If the engine overheats and seizes, you’re supposed to stop and have a cigarette while it cools. That’s actually in the book.”

We left Nashville on a Monday and made Natchez on Tuesday night. Wednesday was reserved for rest, so I worked from my hotel room. At lunch, I borrowed Jeff’s Fiat 500 to run an errand. After nearly 500 miles in the Heinkel, the Fiat felt like a rocket, complex and fast. It had a hot-rodded drivetrain transplanted from a Fiat 126 and made perhaps 25 hp.

At a stoplight in downtown Natchez, a middle-aged man in an older Nissan Altima rolled down his window and scowled.

“What is that?”

I smiled. “It’s a Fiat!”

“Is that a car?”

“Definitely,” I said.

Silence.

“I . . . promise?”

“It actually runs?” he said.

“I can prove it.”

“Yes?”

The light turned green. The scowling continued. “Have a good day!” he yelled, driving off.

A weird moment. Not as weird as our stop in Tupelo, Mississippi, the birthplace of Elvis Presley, where Patty jumped in her car on a few minutes’ notice after hearing about an Elvis convention downtown, hauling off with me and our photographer, Dave Burnett, to find an Elvis impersonator. (Patty had made a bet with someone else in the group, and she wanted to win.)

But still: pretty weird.

***

Eight hundred miles is a lot of miles. Whole counties were spent pondering only Heinkel engine thrash. And microcars in general.

Origins vary with manufacturer, but the class was essentially born in the Fifties. By the late Sixties, micros were all but extinct, killed off by more practical small cars like the Austin Mini. Machines like the Subaru and Bond carried on due to quirks of their homelands that kept production sensible.

In retrospect, these cars could not have existed much sooner or remained viable much later. By the middle of the last century, wartime pressure had greatly evolved the art of rapid mass-production, improving both its speed and the quality of its results. Microcars were also designed in our last great period of unfenced automotive innovation, just prior to the onset of significant government regulation. The result was a set of quick-and-dirty engineering solutions at a time when an inordinate amount of drivers were happy to take whatever they could get.

Yes, those solutions were often remarkably unsafe and abnormal. Yes, they often came with goofy doors, or bubble canopies, or the cornering stability of a barstool.

Still, what is normal? Take the Heinkel’s “weird” ignition switch—odd, but only next to tradition. And what makes turning a key more logical than pushing it, anyway?

It makes you wonder how many of our storied old engineering conventions are the best answer to a given problem, and how many only seem that way because they’re familiar.

In postwar Europe, micros were a necessity. In this country, during a period of relative prosperity, the cars were simply a reminder that Japan has nothing like a Nebraska interstate, and that no one in Germany has to trudge across 50 miles of snowy plains to reach the nearest grocery. For Americans, that reality made the cars seem like toys. They were mounted on poles outside junkyards and restaurants when just a few years old, carried into buildings as practical jokes, made butt of punchline and experiment.

In Nashville, Larry Newberry, the Vespa expert, talked about buying a 1962 Berkeley three-wheeler some time back. When he got the car home, he said, he saw that someone had screwed grease fittings into the engine’s pistons.

His face wrinkled up. “There’s nothing to grease there! Why would you do that?”

No sense of humor, maybe?

At a Mississippi gas stop, someone asked Sheila de la Porte how fast her Isetta could go—maybe 40 mph? Forty-five?

Game, she took the bait.

“I can go,” she sniffed, “as fast as I want.”

The group burst into laughter.

After a while, flogging the Heinkel—taking and demanding its punishment—became an odd thrill, a kind of neon reminder that we are all alive by sheer chance and could at any point be not. Everything from stop signs to train crossings required a kind of ascetic, think-about-it, walk-on-coals work.

Sheila’s husband, Herb, had alluded to it: Travel with these cars is a drug. And as with any drug, what you get out of a trip has a lot to do with what you put in.

***

At least once a day, somewhere on the road, some bystander or gas-station customer asked me “if you can still get parts for that.” I had no idea, but I knew who to ask, and so I did, at that lunch stop. Some micros are relatively easy to keep in spares, the group told me; others are not.

Relatively is the key word there—because microcar repair is microcar repair, normal goes out the window.

Patty Schwarze: The Messerschmitt club does this brilliant thing—you have to be a member in order to buy parts. It helps keep them alive. Still, everybody here will tell you, they’ve ordered a reproduction part you couldn’t use if your life depended on it, because it just doesn’t fit. Subarus are horrible because nobody kept parts. They were worthless.

Bob Lancaster (Fiat 500): It’s a treasure hunt. When the club tried to get Subaru in Japan to make parts for us, they said, “Call Malcolm Bricklin. He [imported] them. We’re not doing it.”

Raise a hand if you had to restore the car you drove here.

[Most of the table raises a hand]

Patty: Everybody has projects.

Sheila de la Porte: I had the engine in a Tupperware container.

Gene: I’ve had cars that go 0 to 60 in like three seconds, big guys. When I saw this little Vespa, I was like, this is so cool. I restored it, and then the bug gets you more. Now you need the one with this headlight. Then the one with double horns. You just end up collecting them.

Patty: You know it’s going to be this monumental challenge . . . it’s an obsession.

***

We did not make it home. Under Heinkel power, at least.

On the way back north, around 100 miles south of Nashville, at 40 mph, wheel pointed straight, the Kabine began swerving wildly in the lane. I released the throttle and countersteered gently. The swerve grew worse. I added throttle and went back to holding the wheel straight. That made the Heinkel feel as if it were about to trip onto its roof, but on the upside, it produced a comforting quantity of personal clenching.

I nudged the wheel toward the shoulder. The Heinkel darted into the oncoming lane, then back toward the shoulder. Several sweaty moments later, we were parked in a turn-off. The engine idled merrily, wocka-wocka, unperturbed.

“You would have been fine,” I said, aloud. “Tiny car. Only a tiny bit dead.” Then I smiled at my own stupid joke, because black humor is still humor and microcars are always funny, even when lightly murderous.

A few of us lay down beside the Kabine and poked at suspension bits. Jeff Lane suggested we err toward caution and trailer the car the rest of the trip. His museum mechanics would later discover that the car’s leading swing-arm mount bolt had simply removed itself from service, letting engine and rear wheel flop around with load.

I spent the remainder of the day riding passenger with Wayne Saunders, talking history in his Subaru. He told stories of running the Alcan 5000 rally in the Eighties and of growing up in Fifties Oklahoma, where he rode a motorcycle through the halls of his high school.

Lovely man. Quiet and witty. Not the sort you’d peg as an old-world hooligan, but you know what they say about books and covers.

It was a strange week, a whirlwind of surprises, of boredom and delight. I do not want to do it again, and yet I also want to repeat the trick tomorrow and forever. This is the microcar paradox: You are at times a little miserable, but it is a good-natured and refreshing misery, born of perspective. The high points are made even higher because you have had to sacrifice to reach them, and because you have subjected yourself to the whole thing on purpose.

No one takes a long drive in a short car because they think they know how the world works. Maybe, however—just maybe—they have a bit more handle on that than the rest of us.

***

Want more stories from our Great Reads project? Click here.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

You had me at, “Wocka-wocka.”

I would literally read a menu if Sam Smith wrote it.

Oh, man. Imagine the menu…

Great read, thanks! Originally from France, it should be emphasized that back in the ’50s to early ’60s, these cars were not referred to as “micro” in Europe; they were “regular” cars for everyday transportation and one could even see people driving them cross country for a summer camping vacation, accessorized with luggage racks and/or tiny one wheel trailers. For my part, I own 2 Citroen 2CV, which, although they are only 602cc, look like SUVs when parked next to any of those micro cars, even next to an early Austin mini. I drove my 2CV from Chicago to Amherst, MA for the ICCCR meet, drove it then from Chicago to Phoenix when I retired. Also took it on a rally into Baja, CA and Mexico, another trip to Pismo Beach, CA……I totally relate to what Sam says about the self imposed pleasurable misery when at the wheel of such a vehicle. I say it is “therapeutic”….makes you feel good, it’s that simple!

Reading this article made me wonder which of the following statements is the more true: Automotove journalism really needs Sam Smith to maintain its perspective or does Sam Smith need automotive journalism to help maintain his own particular grip of reality? Upon reflection, and without any intoxicants involved, I’ve decided that with so many great Sam Smith observations, plus the miniature rubber chickens, that both are true. Thank you for this wonderfully-entertaining article.