Ferrari captures the exhilaration of victory—and its dreadful cost

“Jaguar races only to sell cars. I sell cars only to be racing.” — Enzo Ferrari, in Ferrari (2023)

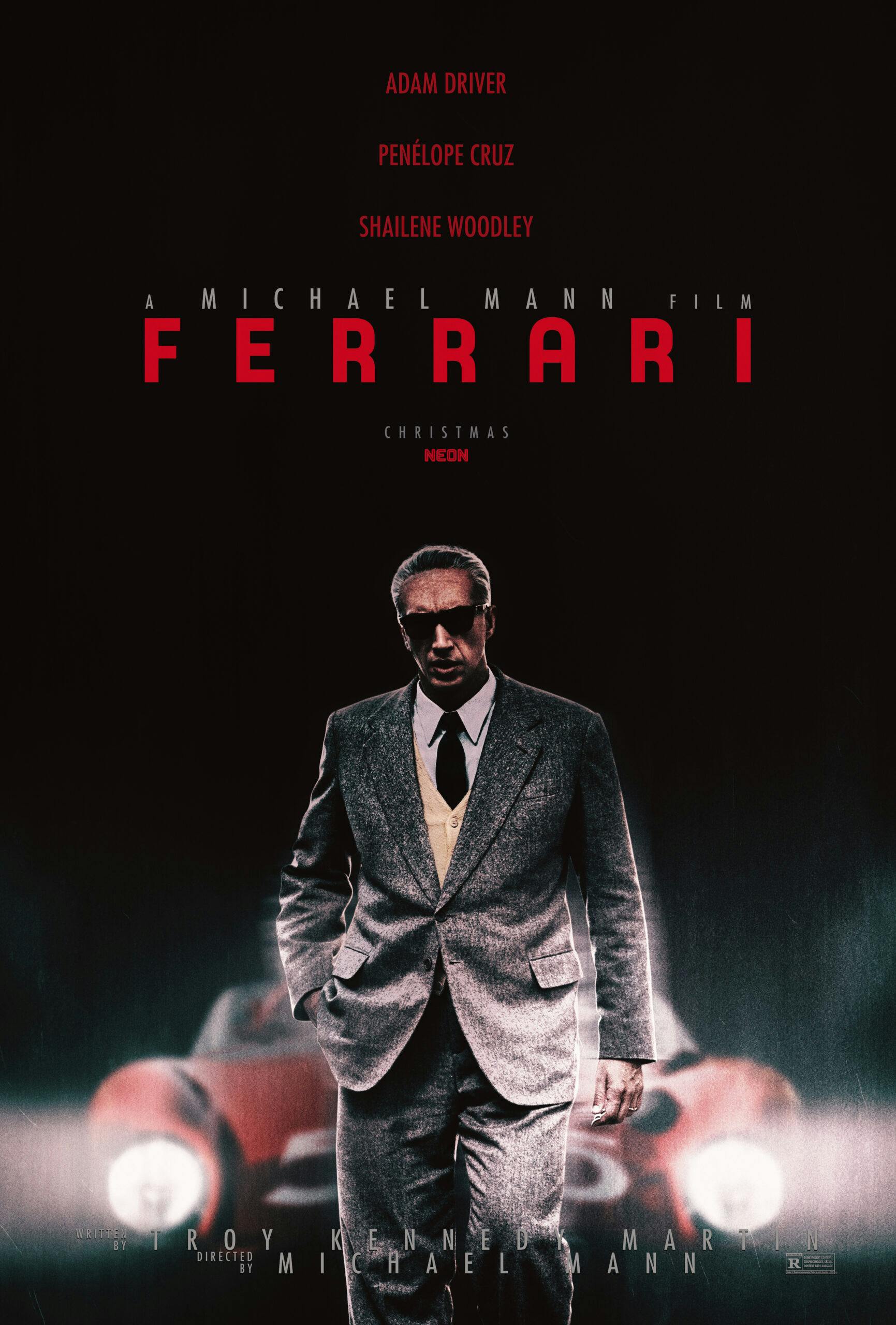

In the life of Enzo Ferrari, 1957 was a fraught year—not to mention a tragic one—amid an especially dangerous era of racing. It’s the moment in history, covering a few brief but critical months, when director Michael Mann chose to set his biopic Ferrari. At this time, Enzo finds both his company and his personal relationships in peril.

When the film begins, we find Enzo (Adam Driver) struggling with his volatile marriage to Laura (Penélope Cruz, the film’s MVP), a not-so-secret second family with Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley) and their young son, Piero, who seeks recognition from his father. Meanwhile, his namesake business is on the brink of failure. The year prior, Enzo’s son Alfredo “Dino” Ferrari passed away at just 24 years old, and the loss casts a shadow over both him and Laura.

To save Ferrari, Enzo’s business manager, Cuoghi (Giuseppe Bonifati), tells him he must win Italy’s Mille Miglia, a sports car endurance race covering about 1000 miles. If successful, he can attract partners like Henry Ford II or Fiat’s Gianni Agnelli, and he can sell more cars, and the business will survive. (As the famous NASCAR adage goes, automakers had a “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” mentality) The difficult circumstances of these months—like motorsport itself—serve as a crucible for the man and the company.

Making Ferrari was, for Michael Mann, a dream that has survived development hell since the ‘90s. (Screenwriter Troy Kennedy Martin, who adapted the script from Brock Yates’ Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, sadly passed in 2009.) Anyone familiar with his filmography will recognize that the subject matter is tailor-made to the filmmaker’s interests, from its fast cars to Mann’s particular brand of romanticized (and often destructive) masculinity embodied by taciturn, driven, professional men. Enzo Ferrari was a self-made man, perhaps the ultimate example of the type, who forged and shaped himself like the metal of his cars.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Though Enzo was in control when it came to his business, his personal life was in chaos. Ferrari thus delivers on the domestic drama front—or rather the flavor of domestic melodrama that serves as a recurring theme in Mann’s movies. In the past, some critics have written off this aspect of Mann’s work as extraneous, but Ferrari underscores that it’s a feature, not a bug; Mann adores a love story, however imperfect or troubled, as much as he adores the obsessive man archetype. In this context Lina Lardi is never portrayed as a mistress but rather as Enzo’s true love, and scenes with the two characters together feel lighter, warmer, homier. As for Laura, she is essential to Enzo’s greatness—an equal partner from the start who co-founded Ferrari with her husband and continues to contribute to its success. It’s a refreshing departure from the familiar wife trope in many biopics about famous men, which frequently depicts some kind of harpy working in direct opposition to her husband’s potential, his ambition, his brilliance.

But Laura struggles with her own emotional turmoil, also locked into her grief over Dino’s passing. Cruz as Laura is both controlled and (delightfully) unhinged; she is smart and savvy, but not above firing a gun in her husband’s general direction to make a point. She is every bit as complicated, contradictory, and powerful as Enzo, and it comes across as a shame that she never gets her proper recognition or respect. (Nor did the real Laura Ferrari.) Cruz expresses all of this in her performance and, together, she and Adam Driver capture the wildness of Laura’s and Enzo’s relationship, the way they were simultaneously attracted to and repelled by each other. Driver’s Enzo mostly keeps us at a distance throughout the film, but Cruz’s Laura feels vital, fully dimensional, viscerally real.

And the cars! They are shot lovingly, beautifully, more like works of art than mere machines. The film showcases Ferrari 335 S, Ferrari 315 S, Ferrari 250 GT, Lancia-Ferrari D50. (Enzo, well-known for his love of Peugeots, drives a decidedly less sexy Peugeot 403.) Gearheads and racing enthusiasts will be relieved to hear that no real vintage Ferraris or Maseratis were harmed in the making of this film; action shots were performed using production-built replicas rendered from LiDAR (i.e. 3D) scans of the real thing. (Even if production had wanted to use them, it would have been prohibitively expensive to do so.)

Mann explained that his crew “designed the tubular chassis to receive the body of the car… and they had contemporary drivetrains and they could do 140, 150 [mph], were reliable, and safe.” The powerplants they used for the replicas were four-cylinders cribbed from Caterhams. (The exception here is the 1957 Maserati 250F grand prix race car that makes a cameo during the time test—a very real car that belongs to Pink Floyd drummer and car collector Nick Mason.) At one point in the film, Enzo comments on his newest Ferrari, perfectly articulating both the awe and dread it inspires: “The driver in front will piss his pants when he sees it in his mirror. And when it passes, it has an ass on it like a Canova sculpture.”

The film presents racing as religion. This is not a poetic invention by the filmmakers, as Ferrari is indeed a kind of religion in Italy. In one scene, a priest delivers a sermon about “the nature of metal,” and “how it can be honed and shaped with your skills into an engine with power to speed us through the world.” He posits that if Jesus Christ had been born then, the son of God might have been a “craftsman in metal” instead of a carpenter. This is a Workers Mass, and so the men in the pews are all car-factory workers themselves; though this sermon is clearly written for them, their attention is divided between God and Ferrari: they pull out stopwatches when they hear the sound of the starter pistol in the distance, as Maserati is just beyond the door, seeking to break Ferrari’s speed record.

And the racing scenes do not disappoint. (My only gripe: there could have been more of them.) They place the viewer in the driver’s seat, capturing both the thrill and the horror of racing in this era. A scene late in the story plays like something out of a war film, somehow both graphically realistic and hallucinatory, as if it’s a nightmare dredged from Enzo Ferrari’s own subconscious. Adam Driver himself described a single-seater as a “moving coffin,” echoing a line delivered by Antonio Sabàto’s Nino Barlini in 1966’s Grand Prix: “Then I go into one of these cars: you sit in a box, a coffin, gasoline all around you. It is like being inside a bomb!”

Mann is known for his painstaking attention to detail, and it brings remarkable, noticeable authenticity to the film that the most knowledgeable, finicky racing fan should appreciate. The actors, for example, were all given race car driving lessons. (There were some notable exceptions, like Patrick Dempsey, who plays “silver fox” Piero Taruffi, who is a real race-car driver and did not require lessons, and Ben Collins, who plays Stirling Moss.)

Shooting locations were frequently the actual locations, like Enzo’s barbershop (the man who shaves him in the film is the son of Enzo’s barber), the exterior of the Ferrari house, and the family mausoleum. Even the wallpaper from Laura Ferrari’s bedroom was replicated for the film. And because the cars they fabricated didn’t sound quite right (four-cylinder engines sound nothing like V-12s), production relied on ADR (automated or additional dialogue replacement): When the cars are racing down narrow streets of Ravenna, for example, they duplicated that in a railroad tunnel in the U.K. with a real Ferrari 250.

Yet some of the movie’s best moments are its quietest, like when Enzo and Laura separately visit Dino’s mausoleum. Enzo speaks openly with him, while Laura only weeps and smiles, as if she can hear her son’s voice. (This is among the very few moments where Driver’s Enzo allows himself to be vulnerable, to show a crack in his well-constructed façade.)

And then there is a scene that crystallizes the film, meaningfully set during an opera, not a race. It is specifically a performance of “Parigi, o cara” from La Traviata, which is intercut with the film’s characters reflecting on memories made bittersweet by the passage of time, by reality and tragedy intervening, while cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt renders the actors’ faces in shadowy darkness like Caravaggio portraits. The film really does feel more like an opera than a traditional biopic; Mann even reuses a bit of the gorgeous operatic score by Lisa Gerrard and Pieter Bourke from his 1999 film The Insider.

Ferrari gives us an intimate look at a man who was consciously unknowable, who maintained an airtight mystique. In the press, Enzo Ferrari is dubbed a widow-maker, “an industrial Saturn devouring his own children.” He often feels more like a man sending his soldiers into battle than a businessman, writing off the deaths of his racers as if it’s simply the cost of war. But Mann attempts to show us that while we saw coldness and dispassion, it was grief that ossified the man’s heart. In addition to the death of Dino he also lost two of his friends at Monza back in 1933—Campari and Borzacchini—who both died on the same day “in the metal I made,” Enzo confesses. In response, he told himself, “Enzo, build a wall. Or else go do something else.” He built the wall, but their ghosts haunt him nonetheless.

Mann’s and Driver’s take on Enzo Ferrari feels like a reflection of the ethos that people associate with the brand: often at the top of its game yet constantly improving, forever chasing something better, more efficient, more perfect. His race cars are like him, powerful yet fragile, undone by a sticky gearbox, a faulty steering column, an unexpected cloudburst, or just a bit of debris in the road. Il Commendatore was many things: “the Sage of Maranello,” a celebrity, a mythic figure, a martyr, a national treasure, his company regarded as a jewel in the crown of Italy. But the “great engineer,” capable of bringing his foundering business back from the brink, was still a man, powerless to save the life of his own son. With surgical precision, Ferrari identifies and explores the godlike legend figure who is unable to play god when it matters most.

There is no easy, tidy resolution in this film, no hard-won underdog victory as in Ford v Ferrari, no triumphant success story that one might expect from something lighter like Gran Turismo. Instead, Mann gives us a melancholy, incisive look into a man of contradictions, and into the race-car driver’s paradoxical love of racing: you never feel more alive than when you are speeding along the precipice of death. Ferrari captures the addiction, the exhilaration of being one with a race car, the heady thrill of winning—and the unimaginable cost that it levies. As Enzo Ferrari tells his drivers: “We all know it’s our deadly passion, our terrible joy.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Am I the only one reminded of David Byrne in his big suit at the beginning of Stop Making Sense when you see the promotional image of Adam Driver as Enzo?

Thanks, now I can never not see it that way.

“…And you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile”

“…You may ask yourself, “Where does that highway go to?”

Great review. Looking forward to seeing this movie.

“… there’s water at the bottom of the ocean”

now that Ferrari’s don’t have clutches, they are no longer a sports car!…

Enzo was a very complex man and had a very complex life. I really don’t feel his life could be easily captured in one move. It really would take a mini series.

As for joe accurate this movie will be in I will cut them sone slack as Enzo really kept much close snd even those near him really new only some about him.

Here in Ohio I gave hear from a couple people who dealt with him from the tire companies. They only knew do much.

The book Brock did was good but not 100% accurate either.

Enzo was driven to race and to win. Drivers often were just parts of the car and when they failed to win or live he would just replace them.

Many think this was cold but back then many died and you had to num yourself to the fact you may lose a driver per year. They were in cars made of magnesium and gas and like Dan Gurney would not strap in duevyo fear of bring pinned in a burning car. They wanted to take the chance being tossed out.

Enzo only paid homage to one driver.

He mourned a son who died and mostly ignored a son that lived.

Ferrari is hero and warrior while a flawed human all at once.

I expect this movie to be better than most but just due to the topic it will not be one you leave with an all feel good that the hero wins movie.

If you just sit in a F40 the last car he did you get a feel for what the man was like. If it did not make the car faster he had no use for it. His life was built around this. When you pull a wire to open the F40 door it says a lot.

Well-written, Priscilla!

I have no long-winded assessments of the movie as I have not seen it yet. But I am looking forward to the opportunity.

Perfect response! I appreciate brief comments.

If you want a Ferrari movie more about Enzo at a point in time in the history of the company, this movie is for you. If you want a Ferrari movie about racing, the Shell commercial from 15 years ago is a better bet. Just watch that 10 times and you are better off than the movie.

There is some racing but it has none of the magic that Ford vs. Ferrari or Rush did and doesn’t even give you goosebumps like the commercial below does.

What struck me about the movie most was that, and I don’t know anything about Enzo Ferrari other than the racing and automotive empire that he built, is there is no way in hell he would have been like Adam Driver portrayed him. Why they chose him, or wrote and directed him the way he was is beyond me. So many times I kept saying to myself, I don’t care about this, where are the cars?”

Should you see it? I guess. But streaming F vs. F again is probably a better use of racing movie consumption time.

Spot-on in your assessment Shaun. NOBODY wanted this movie to succeed more than me! Unfortunately it was a massive disappointment on every level. I don’t blame the Actors as much as the screen play, directing, cast, and fx. The only bright spot was Penelope Cruz’ performance. I got so bored of all the old pedal-to-the-medal-pass-on-the-inside cliche racing tropes that turned it off DURING the Mille Miglia race. Save your hard-earned money!

You got that right — the WSJ auto writter who claimed this as the “best car movie ever” and didnt even compair it to F vs F or Rush or Grand Prix should find his life’s work somewhere else

I grew up with a love for Ferrari cars. If they had faults, I never knew, as they were simply works of art that made glorious sounds while going fast. I lusted after a Dino when they seemed expensive but possibly attainable. Alas, as I came to have enough money to buy one, they kept getting more expensive. I still think it’s one of the best-designed cars ever. I couldn’t pick a singular best, but the competition would be other Ferraris. Enzo and Pinin Farina made a good team.

I’ve enjoyed a couple of “lesser” Ferraris and had my long-standing personal-best land speed record in one until I broke that record this year in another Italian work of art. I’m looking forward to enjoying this movie on the big screen.

Looking forward to seeing the movie. Especially seeing the racing driving scenes as shown from the driver’s perspective. It sounds like it is a movie that non-racing fan people can watch without being a movie just about racing. Sort of in the same type story as”Worlds Fastest Indian”, where it was a movie centered around the racing and struggle to win, but had the human elements of the story that enabled a wider audience and appeal to non-racing fans.

When did Caterham make motorcycle engines?

Hi Csaba, thanks for pointing out the error, I’ve updated the story.

No problem. I look forward to seeing the movie.

Wow, is this *the* Csaba Csere? I’ve been reading you in print since I was a teenager. 🙂

It’s nice to see an expert here. I thought the same thing when I read the part about Caterham motorcycle engines. Only I figured that must have been information about the company I’d never heard before.

Finally a movie about Enzo Ferrari. Now how about one about Colin Chapman. Oh wait! How about “Chapman Vs. Ferrari?

I guess that if you are into John Wick or Mad Max, this may not be your film. As mentioned previously,

“The World’s Fastest Indian” may be closer to “Ferrari” than “Ford Vs. Ferrari”. Otherwise, you can watch “The Green Helmet”, “Grand Prix”, “LeMans”, “The Racers”… Whatever. I have not seen the film. Tomorrow… I do have a close friend who saw the film at an advance preview last month, and he knows about the art. He said the most important thing about any racing film; “It’s not dumb”. Also noted that it had a good story, about an era that most don’t know much about, especially if they are Gen X~Z. No Enzos here. More depth into where the company came from.

It would not end well with a Heart attack and Delorean investigation.

Perhaps we’re reading Shakespearean tragedy into the tale of an automaker, with resultant pile-on corporate journalism me-too reviews. Didn’t we do this 35 years ago with a rosy, inaccurate, if entertaining Tucker: The Man and His Dream?

Paramount releases a car flick and the attention-starved trip over themselves with accolades and critiques.

Can you see Miramax, Sony Pictures, etc. promoting a movie able to encapsulate the breadth and scope of Walter P. Chrysler, Errett Lobban Cord (without once mentioning the bogus “265 hp”), Sir William Lyons, Harry Stutz, and a hundred others?

It’s not lost on us that as Christmas becomes increasingly replaced by affluenza, it would be a movie about a brand even non-car folk instantly recognize as upscale.

Don’t get us wrong. Am sure young Adam Driver did his best rattling around in the oversized suit, and that it’s a fun movie for starved buffs seeing anything wheeled on the big screen as their day in court.

Bad pictures to show with the story.

Will see it tomorrow.

I think the Enthusiast would have liked a movie similar to the Bruce McLaren movie. Semi documentary like.

As a driver, I saw it yesterday and I have found the above critique more interesting than the actual movie. If you don’t get your hopes up, you will enjoy it for what it is. Not at all a typical Mann movie that stirs you to your bones except maybe the horrific incident associated with the Mille Miglia.

If you’re a Ferrari fan, I think the most useful thing I can say about the film is to go in with absolutely no expectations and you won’t be disappointed. Know that the film covers just two months in Enzo’s life and focuses primarily on his relationships with wife Laura and his mistress Lina Lardi and their son Piero.

Beyond that, you are plunked-down, smack dab in the middle of his life with precious little context to help figure out who this complex man is and what forces shaped him.

The few “racing” scenes are more ‘Ford vs. Ferrari’ and ‘Rush’ than ‘LeMans’ or ‘Grand Prix’, but the cars are gorgeous and the SFX used for a couple of the crash scenes verges on the spectacular.

To sum it up, ‘Ferrari’ is a Reuben sandwich without the sauerkraut, Swiss cheese, and Russian dressing. 😹

I just hope that some day, somebody, somewhere produces a proper Enzo biopic because THAT would be a film/series worth seeing.

Thank you for the well written review.

Wonderfully accurate review of the film, Priscilla. Your article captured the essence of the film the way the movie captured the essence of Il Commendatore at a time of great corporate and personal stress.

Enzo’s life and Mann’s story and direction were both absolutely operatic in execution. Erik Messerschmidt’s breathtaking cinematography was an incredibly detailed and moody time travel back to 1957 Italy.

And thank you Robert Nagle. I was actually never more alive or terrified during those racing sequences. And I agree that you can never have enough footage of cars in an auto biopic about racing.

So bravo, Priscilla. A great, in-depth review of complicated, genius souls. Especially the one executed by Penelope Cruz. I thought she stole every scene she was in. Oscar worthy!

But the scene that stole the movie for me and summed up the complex personality of Enzo, was when he and Peter Collins and his girl friend/actress Linda Christian were standing for the press in front of Pete’s 355S, and Enzo pulls Linda in tight towards him to reveal the Scuderia Ferrari crest on the fender for the press.

Power, Ego, Confidence, Leadership, Flirting and Control, all rolled up in one scene. Nice touch Michael Mann.