Driving the Mercedes 300 SLR “Uhlenhaut coupé”—the world’s most expensive car

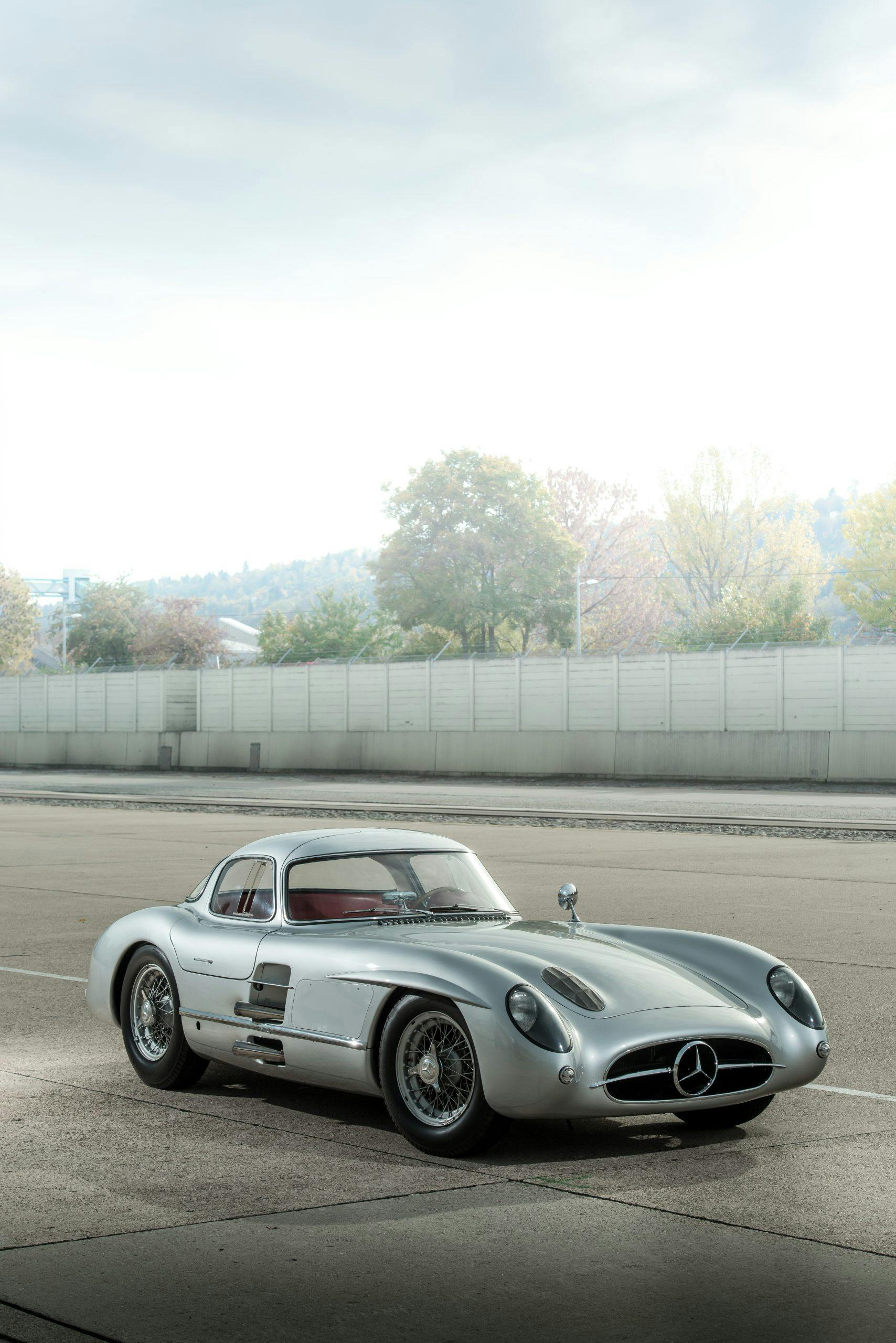

It is said that everyone at Mercedes-Benz knew when Rudi Uhlenhaut was on his way to work. The distant howl would stop typists typing, and turn ears to the direction from whence it came. It got louder and louder until it became a bellow, shortly before turning into a beautiful silver coupé nosing its way through the gates. Then silence. Herr Uhlenhaut was in the building.

The car is today known simply as the Uhlenhaut coupé. Yet as of last week it had earned another more sensational label—the title of most valuable car in the world.

Hagerty was first to report the news that one of the two Uhlenhaut coupés built had been sold by Mercedes for a sobering €135 million or $142 million, Until that sale happened, the other car most regularly touted as the world’s most valuable car was its sister, the 300 SLR in which Stirling Moss won the Mille Miglia. Yet the Uhlenhaut coupé is an SLR too, made at the same time as part of the same run of ten cars.

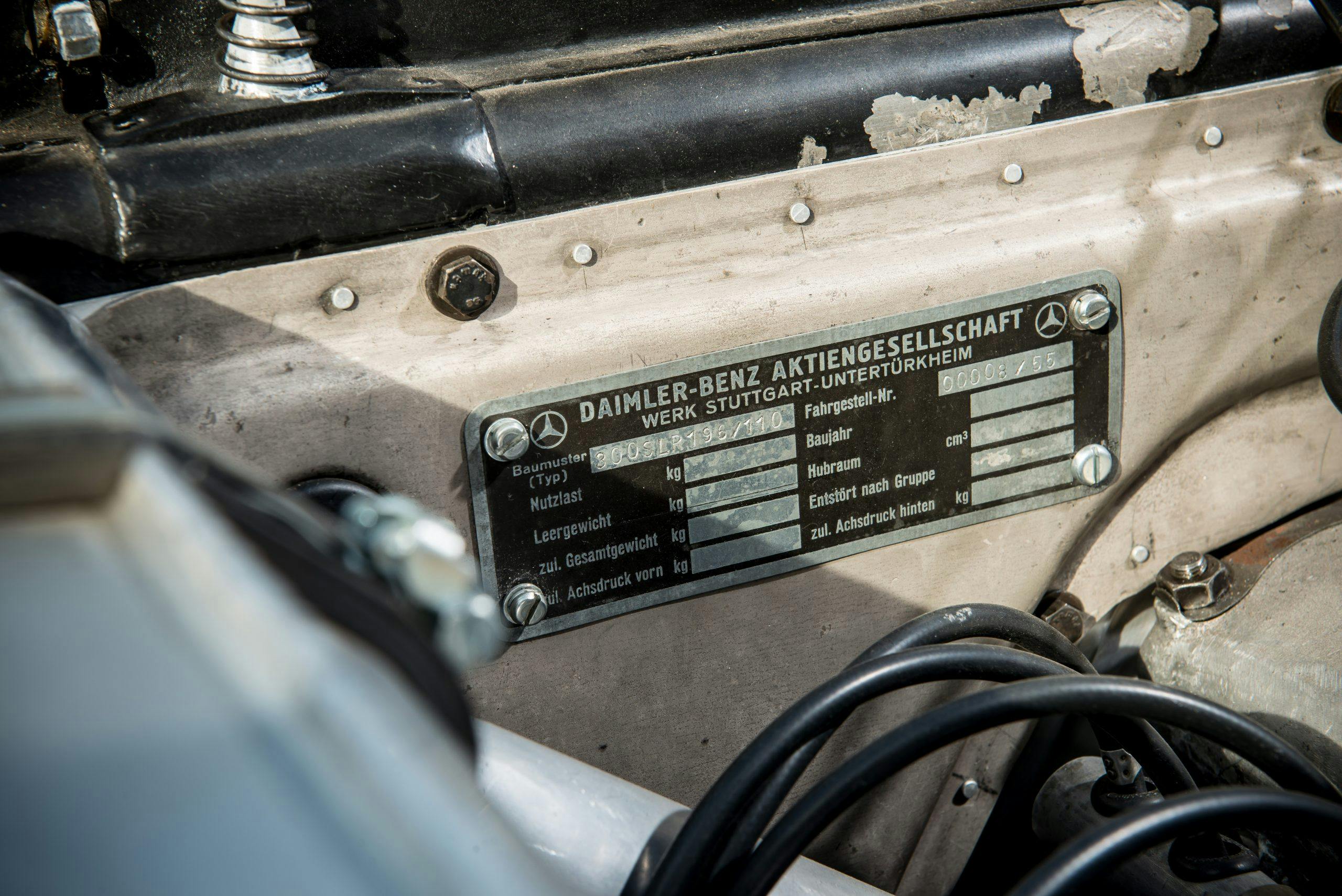

Few industry veterans saw that coming. Most assumed the two coupés were sacrosanct to Mercedes, and would never find their way onto the market. Of the pair, chassis 0007/55 sports blue upholstery and is a permanent exhibit at the Mercedes museum in Stuttgart. Whereas chassis 0008/55 has been maintained in running condition by the factory.

It was intended that they would be raced in the 1956 season, and had the team stayed in racing beyond 1955, no doubt that would have happened. But in the aftermath of the Le Mans disaster, when the 300 SLR of Pierre Levegh was launched into the crowds of spectators, Mercedes retired its works team and the coupés became fabulous “what might have been” machines, in much the same vein as the Jaguar XJ13.

What this means, of course, is that both cars are in perfect, original condition. So when you sit in 0008, the pedals you press, the dials you see and the wheel you hold are those that would have been pressed, seen and held by perhaps Germany’s greatest race car engineer.

I say Germany, though Rudi Uhlenhaut had an English mother and was born in Highgate in 1906. He came to prominence in 1936 when he worked out that the reason the W25 Grand Prix car was difficult to drive and increasingly uncompetitive against the Auto Unions was that there was more flex in the chassis than the suspension, making the frame its unintentional primary springing medium. His W125 of 1937 addressed the problem and from then until the outbreak of hostilities, Mercedes ruled the racing world. It was Uhlenhaut too who brought an impoverished Mercedes back to racing in 1952 with the superbly pragmatic and effective W194 coupé which won Le Mans, the Carrera Panamerica and which would spawn the legendary 300 SL “Gullwing”. And it was Uhlenhaut who engineered the W196R Grand Prix cars of 1954-55 and their 300SLR sports car equivalents, coupés included.

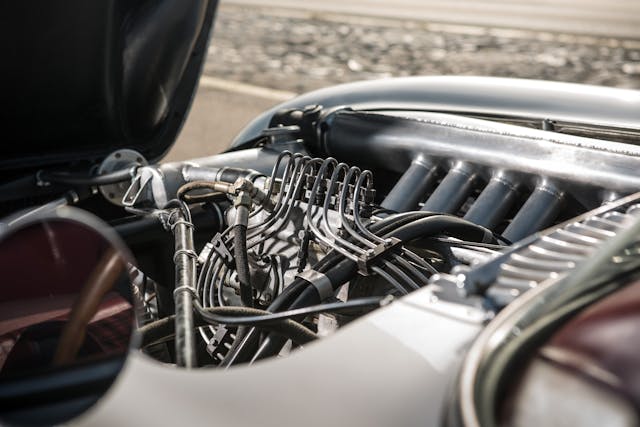

The coupés are mechanically indistinguishable from the SLR roadsters. They share the same 3-liter, straight-eight engine, itself a slightly bored and significantly stroked version of the 2.5-liter Formula 1 motor, albeit it with a different firing order. The cars even sat on the same wheelbase as the F1 cars, though to be strictly accurate it was the longest of three wheelbases available to the Grand Prix machines. Suspension is by double wishbones up front and dubious swing axles at the back. Braking comes via drums all round, mounted inboard to minimize unsprung weight.

Because it has gullwing doors and 300 SL as part of its title, it’s tempting to look at the Uhlenhaut coupé as a kind of 300 SL turned up to 11. It is nothing of the sort, as a pure SLR it is unrelated to the SLs and you only have to slide over its wide sill and drop down into the tartan-covered seat to know it. You sit legs akimbo, the clutch displaced some feet to the left of the brake pedal, just as in the W196 F1 car. Road-legal though it is, this is a racing car through and through.

And if you doubt that, turn on the fuel pumps and magneto, prod the starter, and prepare for your ear drums to be assaulted. Straight-eight engines sound pretty different and this one, unsilenced and with its Desmodronic valve gear (where an active finger rather than a passive spring actively returns the valve to its seat), plays curiously tuneful thrash metal between your ears. I’ve been told one reason the car didn’t race in 1955 was its drivers feared they’d go deaf in a cabin that doubled for an acoustic chamber. At least in the open SLR the sound was dispersed.

My earplugs seem entirely inadequate, but right now there is something worrying me far more. I’ve raced very elderly machinery for decades so I am both familiar and comfortable with all sorts of eccentricities: center throttles, manual fuel pumps, rear wheel brakes, and so on. The SLR has a center throttle too, but it’s the gear layout that’s really troubling. If it were simply backwards like that of a pre-war MG or Aston Martin, I’d not give it another thought. But it’s not: It has three planes as you’d expect and the lever moves to the right as you go through each pair of gears. And first, third and fifth are exactly where you’d expect—top left and top middle and top right. So what’s so troubling about that? Only that second is directly below third and fourth directly below fifth.

Just consider that for a moment. You’re accelerating hard in third and want fourth so you do what comes naturally and pull straight back. Which gives you second and Mercedes a bill I’d rather not think about. Worse, imagine you’re in fifth and braking for a corner, so your hand guides the lever one place across the gate and back into what your brain insists is fourth. But it’s our old friend second again. Desmodronic engines are legendarily strong; Fangio is reputed to have buzzed his past 10,000 rpm and got away with it, but I expect a fifth-to-second downshift would still turn the insides of those elegantly crafted cylinder heads positioned as two groups of four with a central power take off, into shrapnel. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t on my mind a bit as I took off around Mercedes’s Unterturkheim test track in the world’s most valuable car.

Perhaps you’re tempting to suppose this is the part of the story where I reveal it’s a surprisingly easy car to drive after some acclimatization. But it’s not, because you have to think about every single gear shift you can’t relax for a minute. And even if you could it would be a bad idea because the brakes are terrible. They’re not very good at high speed and just get worse from there. No wonder they had to put airbrakes on the SLRs at Le Mans in 1955 to counter the threat from the disc-braked Jaguar D-Type.

But it is so worth it: that hellishly noisy engine is one of the greatest racing powerplants ever conceived: more powerful and more reliable than any contemporary power unit. And despite those swing axles, it handles really well. You just drive it like an old 911, being quite conservative on entry but regaining time lost by getting back on the power as early as possible. Traction is good, enough for it to understeer a bit and, no, I didn’t think it the time, place or car to have a big lift and see what happens when the other end lets go.

Just to see Rudi Uhlenhaut’s masterpiece in the metal is a rare and special moment, for it is truly a stunningly attractive car. But to drive it, hard, and experience the same sensations he did all those decades ago is a privilege afforded to but a handful of people since. How lucky I am to have been one of them.