We fell out of love but I’ll stick with my Mini Marcos to the bitter end

There are days when the decision to blind-buy a barn find still haunts me. When, in what might be interpreted loosely as moments of clarity, I wonder why someone whose mechanical skills stretch barely as far as changing a tire decided that rebuilding an obscure and neglected 50-year old British sports car was a good idea. For months that quietly became years, that car has been a monkey on my back, languishing out of sight yet never quite out of mind. But I’ve recently come to accept this stagnant status quo, to positively embrace it. I’m never going to finish restoring my classic car, and that’s absolutely fine.

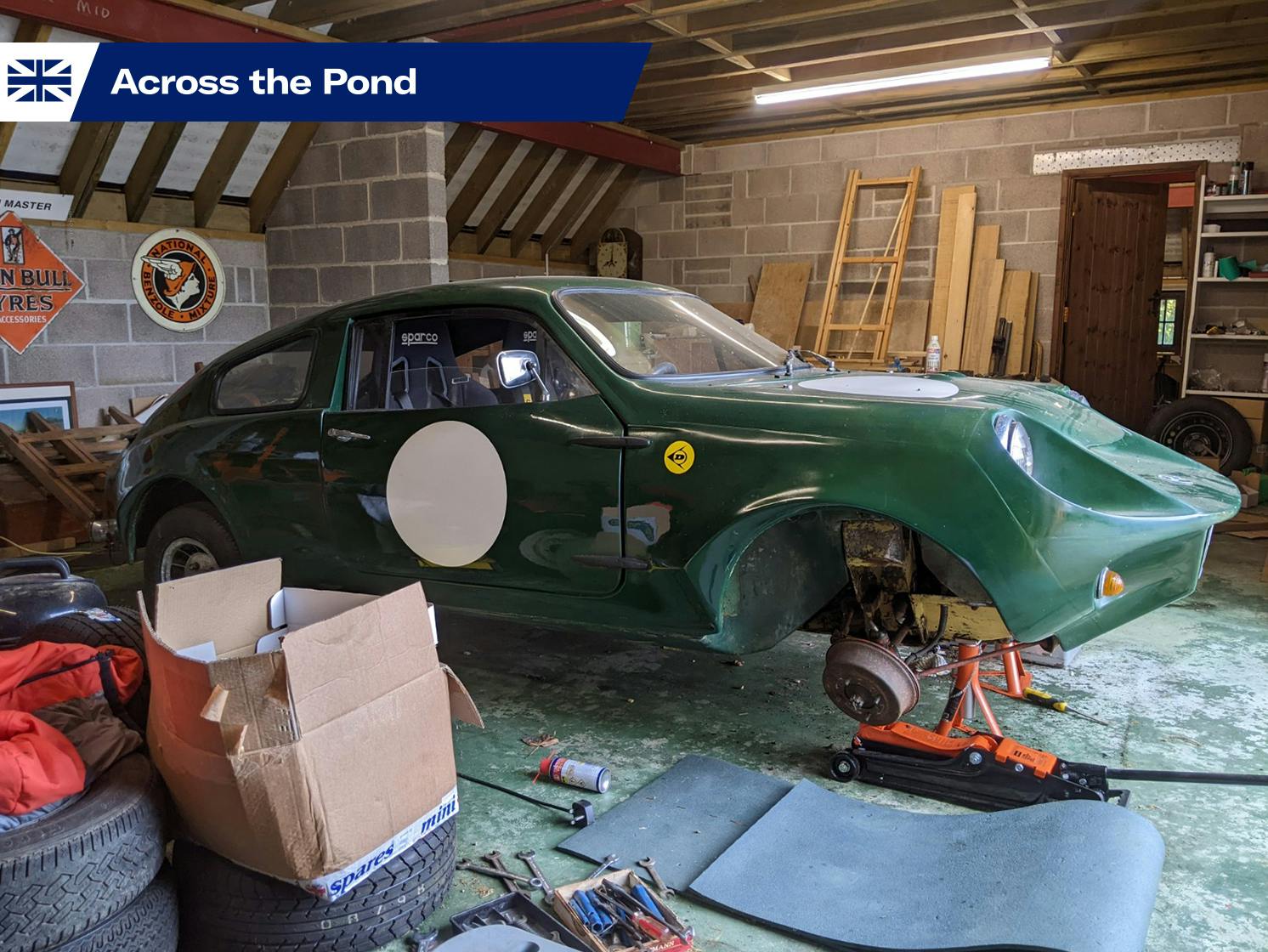

The car in question is a Mini Marcos, a tiny and sinfully ugly fastback coupé using Austin Mini running gear and subframes bolted to a fiberglass monocoque. These cars made a name for themselves in the mid-1960s as affordable club racers, giant killers in the right hands, whose lightness and handling made up for the extremely modest output of their A-Series engines. Mine, however, was a later model, built by the decidedly unglamorous-sounding subcontractor D and H Fibreglass Techniques and mated to the underpinnings of a 998-cc 1973 Mini Clubman. What little other history there is suggests it had been used in regulation rallies for a few years before being abandoned to a shed for the best part of two decades. A harbinger of life to come, as it happens.

Part of the joy, perhaps most of the joy if we’re honest with ourselves, of classic car ownership lies in the initial search. Settling on the “right car” for you, spending countless hours trawling classified ads, watching online auctions, index finger poised to bid, before changing your mind entirely and latching onto something completely different. Rinse and repeat. The problems only arise when you start to take your whims too seriously. When an initial enquiry leads to a series of increasingly earnest emails, worse still an actual phone call, and before you know it a car you have only ever seen in grainy low-res images is on a flatbed, en route to your house, life savings consequentially dented. This happens to everyone, right?

It would be convenient to offload at least some of the blame onto the pandemic, the get-out clause for all manner of purchases, projects and fool’s errands over the last two years. But the truth is I’d been window shopping for months, if not years, before the pandemic arrived to absolve all car enthusiasts of responsibility for their impulses. Besides, my Mini Marcos (even the name isn’t a good one) actually arrived in February 2020, a good month before the first lockdown. That timing, as it turned out, would be exemplary, preceding a rare window of enforced downtime along with the equally precious energy and enthusiasm that reliably accompanies the arrival of any new toy.

Deposited without ceremony on the driveway, my first task was to get the car stowed away in the garage so I could begin the complex journey through denial, remorse, and acceptance to more denial. The previous owner assured me the car would start and it did, on the button. But driving it into the garage was still going to be difficult. At 6 foot 2, I exceeded the maximum allowable driver height by a good six inches and was forced to sit with my head sandwiched painfully between roof and right shoulder, the world now turned through 90 degrees. But it was running, so a pre-storage test drive seemed essential.

Amid the disorientation and discomfort, a quick loop of the village revealed that this was by some margin the slowest car I had ever driven, despite a curb weight in the region of 600 kg (1322 pounds). With no air filter on its ancient single SU carburetor and an apparent absence of any sound deadening, it was also the noisiest. A neighbor’s child turned excitedly as I approached before bursting into tears right there on the pavement. Whether this was due to the noise or styling I will never know, but either way we were on the same page.

Back home, it was easier to get out and physically manhandle the car into the garage than attempt to reverse it in. Once installed, the lights could go off, the doors be bolted shut and the partnership between owner and “project” start in earnest.

What followed, much like a sexual relationship I suppose, was an initial flurry of excited activity followed by a tempering that preceded a lengthy period of inertia. I took out the Mini donor’s seats in order to replace them with something that might afford me headroom. Gone soon after was the carpet, motheaten and manky. A frenzy of online purchasing saw new wheels and tires acquired (prematurely I grant you) followed by an adjustable suspension kit to replace the Mini’s original aluminum cone design. Visions were had, plans were made, road trips plotted, imaginary hillclimbs conquered. The high point came when I applied large, off-white roundels to both doors and hood, hinting at the illustrious racing provenance of a car I could not get to exceed 20 mph with the throttle pedal buried into the bulkhead.

At some point during the first or second lockdown of 2020, things got rather more real with the stripping of the front suspension. This involved the purchase of grown-up things like axle stands and trolley jacks, and the realization that metric socket sets and imperial nuts do not make happy bedfellows. Grease was everywhere, so too rust, and the process of removing one before the other became a daily, dispiriting chore. Soon, what had at best only resembled a car now looked like nothing of the sort. The floor was covered with cans of WD40 and blackened tissue paper, useless wrenches and rounded bolts. Blood had been spilt and sweat sweated; the love affair was over, the real relationship only just begun.

Over two years since it started, we’re still together. But we don’t see each other much. We lead separate lives by and large, and it works for both of us. I no longer spend time I don’t have nor money I have even less of on a fantasy that doesn’t need realizing to be fulfilling. For the car’s part, it remains a winner in my mind’s eye, as viable and desirable a project as it was pre-purchase, a glorious and ambitious “what if?” for the sunnier days of my imagination.

Yes, there are still fleeting moments when I wonder what on earth possessed me to spend thousands of pounds on a pile of plastic, old oil, and iron oxide, especially now that it is worth substantially less than when it arrived. But on balance, I don’t regret it. The Mini Marcos is the sole possession I would save from a theoretical fire, if only it could move and hadn’t—in all likelihood—started the fire in the first place. There is something occasionally but deeply comforting about just knowing it is there. That one day I will go back to it. That a challenge awaits me, a distraction from the day-to-day if only time allowed.

Perhaps somewhere therein lies the nub of classic car ownership; the subconscious reassurance that whatever you’ve started will never really be finished. Because then what? When my father died a few years ago I dragged two unfinished cars out of the space the Mini Marcos now occupies. Far better, I swear, to be outlived by your passions.