Don’t drag me down: 10 cars that mastered aerodynamics

With a drag coefficient of 0.20, Mercedes-Benz claims its upcoming luxury electric car, the EQS, is the world’s most aerodynamically efficient production car. As you’ll soon find out that’s a claim that can only be made when accompanied by a collection of caveats, but it has a strong chance of outselling the small-volume cars to hold the outright title.

The EQS (pictured below) will be Mercedes’ flagship electric car, effectively an electric equivalent to the S-Class, and will even be built in the same factory. But it sits on a purpose-built platform, and without the need to package a combustion drivetrain the company has found the freedom to maximize the car’s aerodynamics—hence the headline figure.

The history of low-drag production cars is a fascinating one, and below we’ve explored ten models to make waves (or should that be make minimal waves?) in aerodynamic progress and listed their coefficient of drag value (Cd).

1947 Saab 92 – Cd 0.30

If ever you needed evidence that early Saabs were built to the same principle as the company’s aircraft, you need look no further than the company’s very first production car, the Saab 92 of 1949.

With a drag coefficient of 0.30, its ability to efficiently punch a hole through the air remains better than that of some modern production cars. Its shape mixes elegant 1940s streamlining ideals with practical proportions that allowed its successor, the 96, to persist until as late as 1980.

While not privy to the kind of technology modern firms have to improve their cars’ aero efficiency, Saab’s engineers clearly pulled a trick or two from the aeronautical playbook. The 92’s flanks were stamped from a single piece of sheet metal, the headlights were flush with the bodywork, and the roofline features that familiar rake of later aero specials. For the 1940s, it was truly remarkable.

1962 Alfa Romeo Giulia – Cd 0.34

The most aerodynamically-efficient shape for a vehicle is, in theory, a teardrop. A smooth shape minimizes drag and the profile, if correctly configured, keeps airflow attached to the surface rather than breaking free and causing turbulence.

It’s a little impractical though, since you’d need to make every car several feet longer to finish off the teardrop shape. In the 1930s, an engineer named Wunibald Kamm, built upon the work of several other engineers to demonstrate that cutting the tail off sharply could be similarly efficient, quickly breaking airflow and reducing the potential for turbulence.

Having demonstrated its efficacy in racing, Alfa Romeo applied it to cars too, including 1962’s Giulia sedan. It didn’t look much like a teardrop—in fact, it was surprisingly boxy. But with the aid of a wind tunnel, cutting down on drag from superfluous details, careful shaping of the surfaces, a curved edge to the base of the windshield, and of course, a “Kamm tail”, the Giulia was the sleekest sedan of its era with a Cd of just 0.34.

1970 Citroën GS – Cd 0.31

1970’s Citroën GS was another proponent of the Kamm tail, but with nearly a decade of aerodynamic advancement over Alfa’s Giulia—and no small quantity of Citroën individualism—the GS of 1970 was another aerodynamic star, with a coefficient of drag of just 0.31.

1955’s Citroën DS was relatively sleek for its era at 0.36, but the GS, designed to slot in below the DS, was a considerable advancement. Much like the Giulia, the GS’ secret was simplicity, with virtually nothing to disturb airflow along its flanks or over the top of the car, while a gently sloping roof and cut-off tail allowed air to break free as efficiently as possible.

Of course, the GS had plenty of other unique attributes, so its aero efficiency is often forgotten. With an air-cooled flat-four engine, self-leveling hydropneumatic suspension and—briefly—the option of a Wankel rotary engine, its low drag was almost secondary.

1982 Audi 100 – Cd 0.30

Aerodynamic cars had in the past been overtly streamlined, with tapering profiles, and organically smooth curves, but the third-generation Audi 100 of 1982 took a predictably Ingolstadt approach to the art of slipping through the air: science.

On the face of it, the 100 doesn’t look particularly sleek, but compared to the previous 100 there were several obvious differences. Bumpers, body moldings, and window glass were now flush to the body, reducing possible areas of turbulence. Windscreen wipers were partially hidden behind the trailing edge of the hood, and base models got clean, flush-fitting wheel trims to minimize turbulence.

A Cd of 0.30 doesn’t look spectacular today—a modern Audi A4 gets as low as 0.23. But compared to other large family cars it was several steps ahead. Ford’s Sierra, itself a big improvement over the old Cortina, was only 0.34. And Audi’s approach, in which conventional-looking cars can be as aero-efficient as more obviously sleek models, is still used to good effect today.

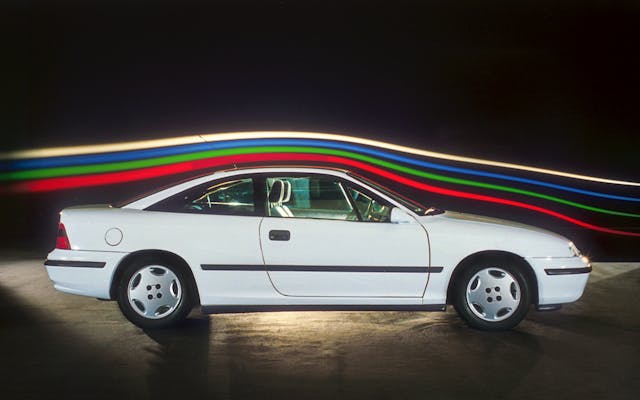

1989 Opel/Vauxhall Calibra – Cd 0.26

The Opel and Vauxhall Calibra ushered in a new, cleaner styling trend for the ’90s when it made its debut in 1989. It was, and still is, a rather fine looking vehicle—minimal in ornamentation, well-proportioned, and as it turns out, very aerodynamic indeed.

The Calibra in fact is one of those cars you could guess was aerodynamic just from looking at it. In profile it’s low and sleek, and at the front its grille openings appear no larger than absolutely necessary, banishing the ’80s trend that favored flat fronts and grilles occupying the full width between a car’s headlights.

Its surfaces were tidy too—check out the flush glass and door handles—and contributed to a drag coefficient of just 0.26. Some modern coupes barely beat that figure today. More performance-orientated versions weren’t quite so slippery, and Cavalier underpinnings rendered it average to drive, but the Calibra always had sleek style on its side.

1996 General Motors EV1 – Cd 0.19

Battery technology in the mid-1990s wasn’t quite up to the level it is today, so early electric cars had to work hard for their range. Or simply work clever, as General Motors did with the EV1 in 1996.

As with the Honda Insight that followed a few years later, the EV1 had just two seats, which meant the roofline could be tailored without reducing passenger space. The electric powertrain meant no need for drag-creating cooling ducts at the front, the rear wheels were covered by spats, and the tail was sharply cut off in the same Kamm style as that 1960s Alfa Giulia.

Powered first by lead-acid batteries and later by nickel-metal hydride cells (which nearly doubled the range to 105 miles), the EV1 would have struggled for a usable range if not for being the most aerodynamic production car ever made. Gallingly, GM killed the project in the early 2000s—very literally, by reclaiming the leased cars and crushing them.

1999 Honda Insight – Cd 0.25

Honda’s first hybrid might look like a sly copy of the EV1 were it not effectively a reimagining of the CR-X that had first launched in 1984. With clean lines, a roofline perfectly angled to keep airflow attached, and a sharply cut-off tail, the CRX already achieved a Cd of 0.32, but the Insight pushed this achievement even further.

A decade and a half of aero knowledge smoothed out the Insight’s most obvious surfaces, but as well as tapering in profile, Honda made its rear track 110mm (4.3 inches) narrower than the front. The rear wheels wore covers too, while much of the underside was clad for minimum resistance.

These characteristics allowed for a drag coefficient well below that of any similarly-sized car, and without the need (or space) for rear seats the Insight had could taper its roofline accordingly. With a tiny frontal area too, the Insight’s aero worked with both its light weight (850 kg, or 1874 pounds) and efficient hybrid powertrain to make it one of the world’s most fuel-efficient cars.

1999 Audi A2 – Cd 0.28

If the Insight showed what was possible by taking aero to the extreme, Audi demonstrated, much as it did with the 100 back in the early 1980s, that with clever design you could significantly reduce drag without compromising packaging for passengers and luggage.

It’s become cliched to call the Audi A2 “ahead of its time”, but there’s really no other way to spin it. Debuting the same year as the Insight, it too used aluminum construction, but unlike the Honda there was comfortable space for four people. The A2 also predated the current trend towards premium materials for entry-level models; Audi has long been a premium brand, but aside from the Mercedes A-Class, few others brought high-end quality to the low end of the market.

Its aerodynamics were the result of clever surfacing and thoughtful details. That tapering roofline was essential (with a small spoiler to reduce lift), while at the front the “grille” was actually a smooth panel, which also flipped down to allow drivers to top off the oil and wiper fluid.

2013 Volkswagen XL1 – Cd 0.19

No other production car has enjoyed such single-minded focus towards fuel efficiency as the Volkswagen XL1, launched in 2013. The Honda Insight got close, but it’s fair to say the XL1 is to economy cars what the Bugatti Veyron was to supercars.

That comparison includes the lofty price, which was just shy of £100,000 in the UK. A bit high for something with an 800-cc two-cylinder diesel you might think, even considering hybrid assistance, but few cars even at that price could boast a full carbon-fiber tub—or a drag coefficient of 0.19.

That Cd figure makes it to this day the most aerodynamic production car ever made—if not built in the same volumes as we expect for the new Mercedes EQS.

2021 Tesla Model S – Cd 0.208

When the Model S debuted in 2012 it did so with a drag coefficient of 0.24. Not bad at all, because while its substantial size meant a large frontal area, the low drag actually made it more slippery than the pill-shaped Toyota Prius.

Tesla has been working hard over the years, and the most recent iteration of the Model S (with Cd 0.208) is, if the company’s website is to be believed, behind only the Volkswagen XL1, GM EV1, and the new Mercedes EQS in terms of production car drag.

The Tesla’s size actually counts in its favor here, because a long body means fewer compromises when squeezing passengers into as aerodynamic a shape as possible. But Tesla has been clever in other areas, refining the car’s shape and maximizing the benefits of features like flush doorhandles and a completely flat floor. We’d put money on Tesla carrying out just a few more aero tweaks to undercut the new Mercedes when it hits market.