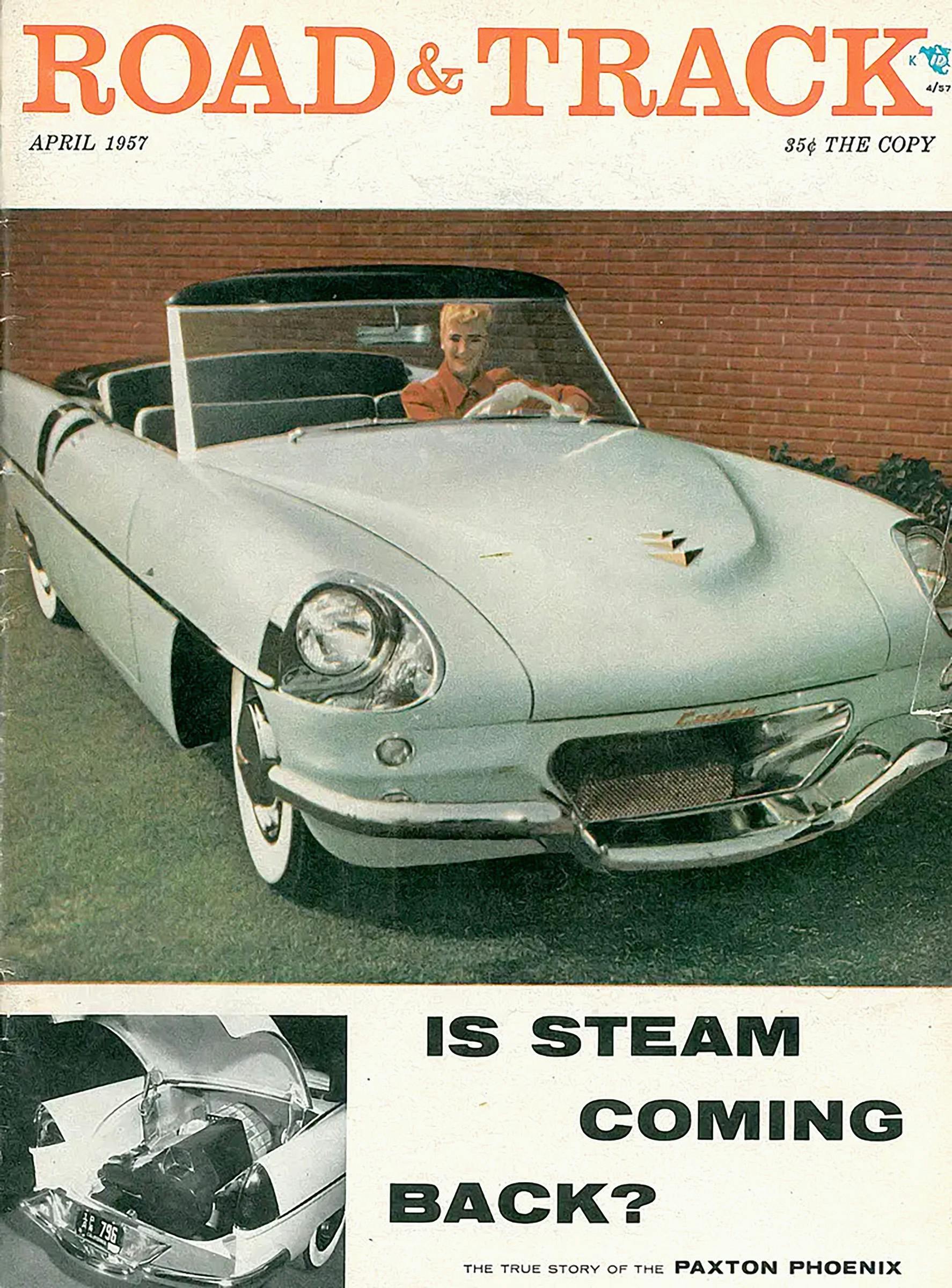

When the Paxton Phoenix Tried to Take Steam Mainstream

The 1954 Paxton Phoenix was the unfulfilled, steam-powered dream of Robert Paxton McCulloch—the same guy who accomplished the unlikely spiriting of London Bridge out of England into the Arizona desert. Moving a bridge from one continent to another is a tough task, but it proved easier than producing a modern steam-powered automobile.

Steam-powered cars were once a workable transportation solution, based on solid technology. They predated the first internal-combustion-engine (ICE) cars of Daimler and Benz by nearly a century. In operation, a burner, which can be designed to run very clean, heats water in a boiler, converting it to steam, which in turn drives the pistons of an engine. Droplets of oil added to the steam flow provide lubrication. In most automotive applications, the steam powerplant was a reciprocating engine, not unlike a typical internal-combustion engine, but with steam pressure rather than fossil-fuel combustion driving the pistons down in the bores and turning the crankshaft.

And until electric starters made ICE-powered cars convenient, steam-powered machines were in important ways more consumer-friendly than their gas-fueled brethren, since they could be started without hand cranking. Steam engines, like electric motors, have a power curve more in sync with the task of propelling a vehicle, so no transmission was needed. The principal drawback was the time needed after the burner was ignited to preheat the boiler and generate steam.

One of the more advanced steam cars was produced by Abner Doble, an inventor who had devised a means of preheating a small quantity of water for quick startup. His 1925 Doble Model E steam car was powered by a four-cylinder compound engine with both low-compression and high-compression pistons. It was ready to drive in minutes after ignition and developed 1000 lb-ft of torque at the rear axle. A perfectionist, Doble built about 40 cars, each somewhat different. He ran out of money before he could mass-produce a final design.

Enter McCulloch, nearly 25 years later. In the late ’40s, following considerable manufacturing and engineering success in automotive-related fields, McCulloch was determined to build a steam car. But it couldn’t be any old steam car. It had to be a luxurious automobile with a stylish shape and an advanced steam powertrain. He called it the Paxton Phoenix.

McCulloch was doing well as America entered the fabulous ‘50s. By 1952, he had accumulated considerable resources, largely as the result of his Paxton Supercharger and McCulloch Chainsaw businesses. Paxton was a standard provider to the auto industry, and his chainsaw enterprise had revolutionized the market just a few years earlier. His wealth allowed him to assemble a steam-car dream team: Abner Doble, the steam-engine expert; Roscoe C. Hoffman, a respected automotive engineer who had developed off-the-grid vehicles; and America’s most renowned designer, Brooks Stevens.

Stevens was the star of the show, having already achieved international recognition for his design work. He also had the advantage of having grown up in an automotive household; his father was an inventor of vehicle components. So the younger Stevens was well schooled in the way things worked and had a natural talent for improving the way they looked. Over his career he focused on automobile design but had dabbled as well in the creation of appliances, furniture, toys, boats, trains, tractors, and motorcycles.

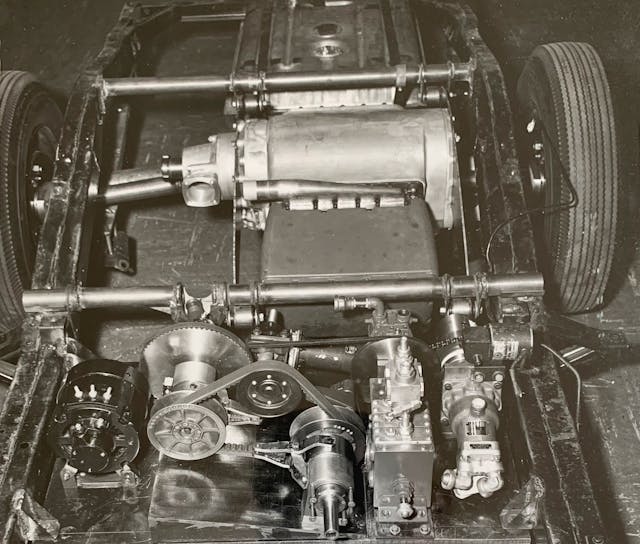

The steam car project was based at Paxton Engineering, a research facility near Los Angeles International Airport that served McCulloch’s growing manufacturing enterprises. Like most good automotive creators, the McCulloch team wanted to start with a rough model, so they bought a Porsche 356 in New York and drove it to Los Angeles, where they fully disassembled it and studied its chassis and suspension design. There, Hoffman created a chassis that combined the Porsche design with aircraft “torque box” construction techniques. The suspension used torsion bars for wheel control, much like the Porsche.

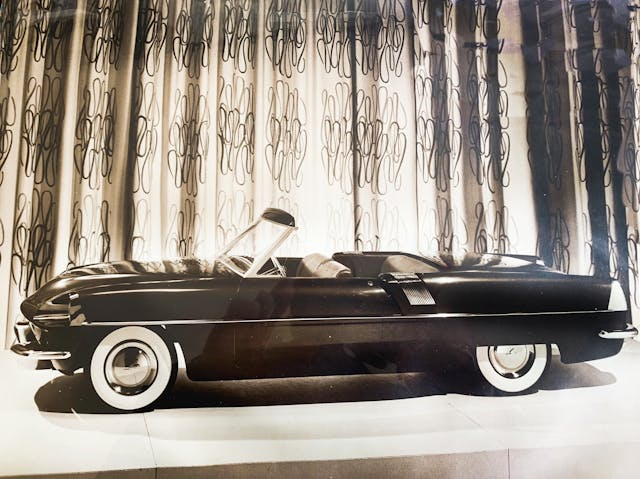

The body was made of fiberglass, an emerging automotive technology at the time. Pioneered by Glasspar in 1949, fiberglass was destined to be the material of choice for the Corvette in 1953, and McCulloch seized on it. In many ways, the material lent itself to limited production. Once a female mold had been developed, bodies could easily be pulled from the mold. No stamping, hammering, or welding needed.

The Paxton Phoenix that emerged from years of design and modeling work was a beautiful car, a uniquely styled machine with headlights set deep in chromed scalloped openings. A belt-line chrome strip ran uninterrupted front to rear. Its hood, with a bulging center that suggested power, sloped down to below headlight level, and a wide shiny bumper underlined its low-slung grille. The rear of the car suggested the form of some of Stevens’ speedboat designs. To complement its stylish body, the Paxton Phoenix was equipped with a fully retractable fiberglass top, which mimicked the shape of the deck lid and covered it when retracted.

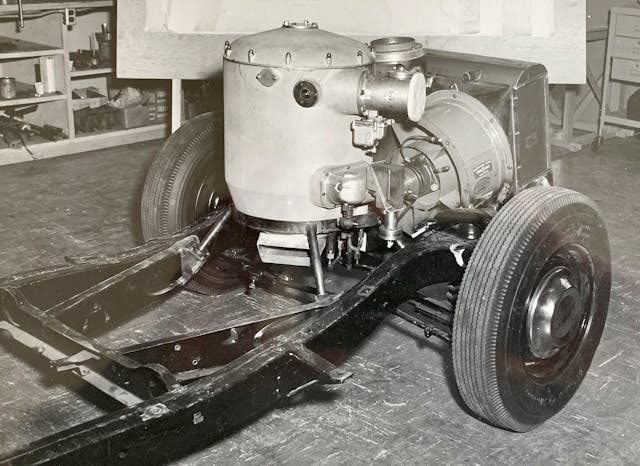

The steam engine that was meant to power the car was an advanced version of Doble’s earlier efforts. A six-cylinder compound design combining low-pressure and high-pressure cylinders enabled the steam to be used efficiently. The high-pressure cylinders were at the top of the block casting, with the low-pressure cylinders below. Steam was expanded first in the high-pressure cylinder and compressed, then transferred to the low-pressure cylinders, which turned a three-throw crankshaft by means of connecting rods. The result was very smooth power, and the engine was said to equal the thermal efficiency of an advanced overhead-valve gasoline powerplant, with the smoothness of a 12-cylinder engine.

Of course, to use steam power you have to make steam. In the Paxton that would be done in a boiler mounted at the front of the car. Automatic controls would ensure the steam could always be delivered to the engine at optimum pressure and temperature. By heating water inside tubing, operating temperature could be reached quickly, and very high steam pressure could be generated without fear of a violent pressure burst since the pipes were protected by a stout aluminum boiler jacket. It’s said that the car could be ready to drive within 20 seconds after startup. Adding water regularly, as had been necessary with earlier Doble steam cars, was unacceptable in a modern car, so the team devised a system that allowed the exhausted steam to condense back into water that could be reused.

A working prototype of the steam engine was developed and installed in a ’53 Ford. At approximately the same time, according to Jerry Williamson, who was foreman of the Paxton shop in the early ‘50s and was interviewed by this reporter in 2011, the Porsche drivetrain was installed in the Paxton so the vehicle could be tested while the engine development continued. By all accounts the steam engine performed well, but at some point, a catastrophic failure occurred. With funds running dry and little interest from private investors, the project was shelved.

McCulloch kept the car in its final form with the Porsche drivetrain serving as its motive power. He is said to have driven it occasionally. When he died in 1977, Brooks Stevens bought the car and displayed it in his personal museum in Wisconsin. Like McCulloch, Stevens never sold the Paxton. He died in 1998 with the car still in his possession.

Enter Myron Vernis, an automobile lover and collector from Akron, Ohio, who fell in love with all things automotive as a toddler in Greece, where he spent many hours watching cars drive by from the balcony of the Vernis family’s apartment. A fan of both 356 Porsches and Brooks Stevens, Vernis flew to Milwaukee the day after he heard that Stevens had passed. He has now owned the Paxton Phoenix for 26 years, equalling McCulloch’s own time of ownership, and he has no plans to relinquish it. Like the Paxton owners who preceded him, he intends to die with the car in his possession.

Vernis has displayed the car often, including at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, the former Meadowbrook Concours, and a number of other venues. It has spent time in the Petersen Museum in California and is currently part of a Brooks Stevens display in the Studebaker Museum. You can see it there until April 1, 2024.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Myron is a local here in Ohio and this car is only the tip of the iceberg. He has some of the rarest and more exclusive cars you could imagine.

Many of his cars would stump many here as to what they are and where they are from.

I met him for the first time when he showed up at an event I was at with a 3 wheeled Davis. I had only ever seen photos of this car and he drove it into the show.

I would recommend that anyone here google and see just what he has. Also check out his book, He has a very good book out too. Amazing collector.

Interesting read. My first thought as I looked at the intro photo of the clay mock-up was “Studebaker”, and it pleased me to read later on that it indeed was some early Brooks Stevens Hawk experimentation. In profile, I thought there was some Lincoln influence on the roofline and from the B-pillar back.

But the biggest question I had when finished with the article? Where’s the 356 body that they stole the powertrain and running gear from? I’ll take it!

What happened to the prototype steam engine and related components? Surely Doble would have wanted them.

The Paxton body has a hint of some Kaiser Manhattan, Packard Caribbean, Datsun 240Z (hoodline/ headlights). The longer you look at it the more you see.

Thanks for this – truly interesting and unbeknownst before today.

Shades of Tuckerdom! What a shame the project was shelved. I assume that McCullough got tired of the ongoing expenditures and pulled the plug… He does not strike me as having been a quitter or a bean-counter, so there must be more of a story to it. Does anyone know?

The Paxton Phoenix is a cool looking car. Would have been cool to see it make production. Steam cars, turbine cars, the roads could have been a bit cooler.

Take a little time and research Brooks Stevens. Everything he touched was a work of art. His designs are still seen and copied in all kinds of things we buy today.

Was there any connection with this and the later 1960s Williams steam car?

Late to the party, but I remember a Williams brothers car made in in Hatboro, outside of Philadelphia, I believe in the late 1950’s. My father owned several steam cars and was very interested in seeing a modern steam car. T. Clarence Marshall was a well known Stanley collector and had converted a Packard to steam by simply installing a boiler and a 20HP engine. The results were mediocre. The Williams brothers, however, had a far more advanced car they were building which I remember seeing in their shop. I believe that they drove it to the steam meet held at Kent State in Ohio which I attended.

The above Paxton article is excellent and makes me want to pull out my copy of R&T with the Paxton on the cover.

Just one minor quibble: steam engines are external combustion, so ECE, not ICE.