The Jeffery/Nash Quad was the Army’s big 4WD upgrade over, well, mules

For hundreds of years, the humble mule has served an important role in the armed forces all over the world. Compact and docile, these surprisingly strong members of the Equus genus have a talent for schlepping packs of equipment, food, and supplies across harsh territory. In fact, long after the U.S. Army had mechanized, as late as the 1950s it was using mules to deal with the challenging southeast Asian terrain during the Korean War.

That being said, the military always longed for a mule replacement. one that didn’t have to be fed, wouldn’t get sick, and was maybe a little easier to transport from region to region. Today, the U.S. is funneling defense dollars to programs like Boston Dynamics‘ Big Dog, a mechanical quadruped that alternately thrilled and terrified fans of robotics with its impressively stable all-terrain antics. Of course, there were many steps between mule and robotic dog, and the automobile is essential to that story.

It’s within this context that, just before the First World War, the United States began to seek a legitimate go-anywhere troop support transport that wouldn’t be flummoxed by the absence of roads. The end result was the Quad, a hybrid pickup/ATV built by Nash that stands as a highly successful 4×4 foray despite its lack of widespread fame.

Farming it out

The initial plan was to develop a solution in house, but after fiddling around with one of the first 4×4 vehicles ever built—the enormous Battleship produced by the long-lived Four Wheel Drive Auto Company—the Army realized it needed something smaller, lighter, and more versatile.

The year was 1913, and officers were hearing significant pushback about the prospect of replacing the difficult, but popular mule teams that were serving as the backbone of military logistics. There was also inertia on the corporate side, with the whole industry’s general reluctance to engage with a government client that didn’t always know what it wanted and was typically not all that excited about paying for it when the bill came due. With the Battleship and its derivatives diverted to more standard support roles, the U.S. turned to the Thomas B. Jeffery Company, the builder of the Rambler line of cars.

Nevertheless, on the strength of personal relationships built by Mr. Jeffery himself, the project moved forward. In fact, it practically galloped: a design for what would come the Quad took shape in a matter of days, and it was less than a year before prototypes were ready for production.

Remarkably advanced

The Quad was aimed specifically at the Army’s desire for a utility vehicle that was small, agile, and relatively lightweight as compared to traditional military hardware. It was also designed to be as cheap as possible to build and equally simple to service when deployed far, far away from a forward base.

To this end, the Quad was motivated by a 52-horsepower four-cylinder engine (built by Illinois-based Buda) that drove all four wheels, sitting atop a 1.5-ton to 2-ton chassis that weighed 5350 pounds. Steering was via four wheels, too, (allowing the vehicle’s rear wheels to follow in the same ruts dug out by the front wheels, with the setup allowing for nearly 90-degree turns) and there were four forward speeds, all of which amplified the “Quad” branding.

The drivetrain itself was an ingenious bit of engineering. The vehicle’s locking Meuhl Torsen-type differentials were located on top of each I-beam axle, which were “dead” in that they only supported the weight of the Quad through to its wheels via leaf springs. Engine power was instead transmitted by way of half-shafts that connected from the differentials to each individual wheel via a spur gear that drove an internal toothed ring gear found in each brake drum. This approach to what we now call “portal axles” not only improved ground clearance, but it also kept mechanical components out of harm’s way in rough terrain.

In terms of appearance, the Jeffery Quad looks as though the designer had stopped halfway through the process and simply submitted a rough sketch of what a truck might look like. Standing at attention at the very front of the frame rails was a radiator for the water-cooled engine, which sat just rearward, under a metal shroud. A pair of headlights sat on either side of the radiator, with a search beam often mounted on top. There was no integral cab, with the driver and passenger sitting on a bench seat mounted across from an upright steering wheel that looked like the spinner on a maritime pressurization valve.

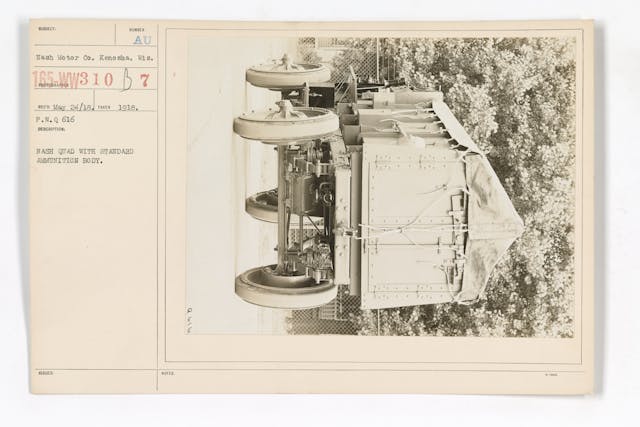

Of course, the Quad’s bare-bones look was a functional reflection of its customizable character. The Army was free to build upon the vehicle’s 124-inch wheelbase as it saw fit for a given mission, which resulted in all manner of configurations being loosed upon the world. Some Quads had a fully-enclosed steel cabin and an open, winch-wearing rear, while others added a canvas troop transport compartment. It wasn’t unusual to see a Quad with a dumpster-like cargo container grafted on to the back, either, with a full-open front making it look like the driver was piloting an overladen skateboard.

Go anywhere, do anything

Army testing revealed the Quad to be nearly unstoppable and certainly within the spec it had asked Jeffery to achieve. The brewing, then exploding European war also attracted overseas buyers (led by Canada), and sales came swiftly. By 1915 more than 16,000 had been sold, include slightly more than two dozen ordered by the U.S. Army to hunt down Pancho Villa in Mexico.

Jeffery, a shrewd businessman, had spent no small amount advertising the Quad’s capabilities wherever he could, and images of it grinding through impossible-looking trails, mud, and rivers were sent out to anyone and everyone who had even a passing interest in the vehicle. He even went so far as to produce an eight-minute long film, called Through The Enemy’s Lines, showcased the Quad’s go-anywhere prowess.

The following year would see the first of two important turning points to the Quad story. The first was Jeffery’s good fortune to survive the sinking of the Lusitania, which prompted him to get out of the car business and start focusing on what was really important in life. Jeffery sold his namesake company to Charles W. Nash, the automotive impresario who would rename it after himself and, after failing to lure away Walter P. Chrysler from the clutches of Buick to take over its reins, run it himself, too.

Next up? War! America’s involvement in the First World War caused a spike in now Nash-branded Quad sales, with the U.S. Army and its allies deploying them in several theaters. The Quads quickly developed a reputation among troops and commanders for their slow, but determined behavior; these 14-mph wonders even acquired the nickname “Wizard” in the Russian army.

A slow slide into obscurity

Depending on how you count, between 20,000 and 40,000 Nash Quads were sold to the military and to civilians between 1913 and 1928 (with the higher number reflecting the startling array of Quad variants available). Armies, farmers, outdoors enthusiasts, and commercial owners would keep the Quad spirit alive well into the 1950s, as their reliability and stout reputation made them hot commodities in a world where four-wheel drive was still a relative rarity.

Today, the Nash Quad is rarely seen among classic truck collections. There’s no doubt that its low top speed and exposed-to-the-elements design make it difficult to enjoy on a regular basis, to say nothing of it being comically unsuited for highway use. Still, although it may be close to forgotten among today’s off-road enthusiasts, the Quad pioneered many of the technologies currently being used by modern trucks to tackle the most treacherous terrain. And unlike a mule, all you have to feed it is gas.