The Founding Fathers of Car Collecting: Waterman & Gibson

Welcome to “The Founding Fathers of Car Collecting,” a new Hagerty Insider series about the titans at the forefront of establishing and defining the culture and trends of the collector car world. Following our first spotlight on the great race car driver and (team owner) Briggs Swift Cunningham Jr. is this deep dive on a pair of collectors who saved the early history of the automobile: Waterman and Gibson.

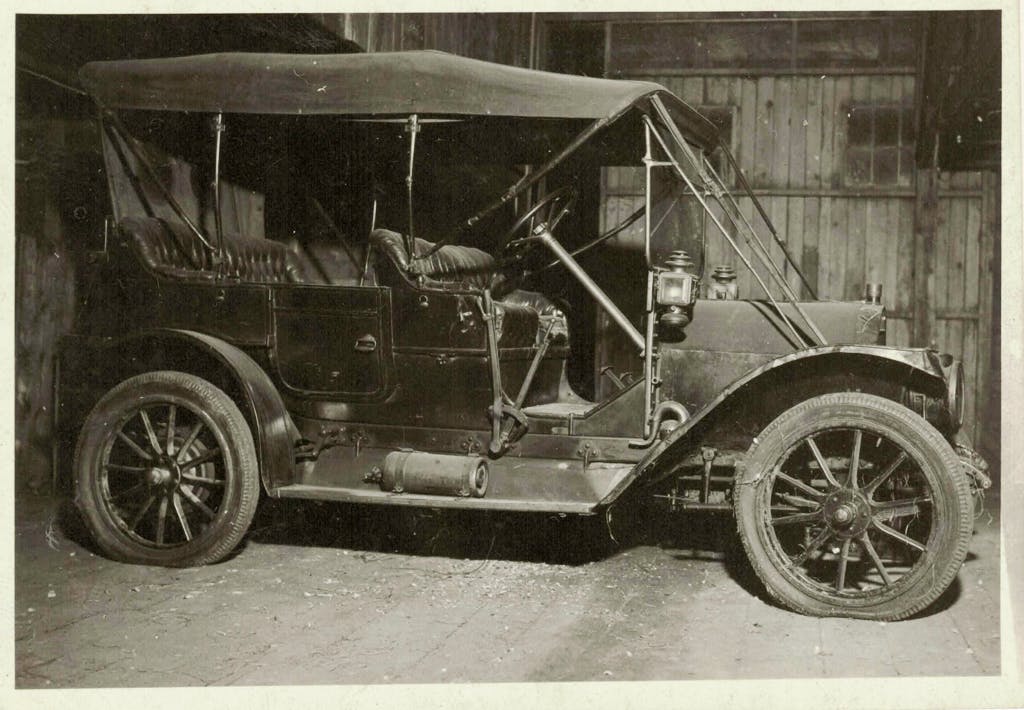

At no point in the history of the automobile did technology advance as quickly as in the early 1900s. State-of-the-art vehicles at the turn of the century were dated in less than a decade and rendered outright relics twenty-five years later. These once bleeding-edge automobiles found themselves superseded by Henry Ford’s ingenious, inexpensive Model T and its scores of competitors, not to mention subsequent luxury brands like Duesenberg. The industrial wave of multi-cylinder, reliable, comfortable vehicles relegated the more fortunate early cars to back corners of barns while others, less lucky, rusted back to the earth in fields.

No one cared about the pioneering products that ushered in the age of the automobile. Except, that is, for a pair of teenagers living in New England: Kirkland H. Gibson and George H. Waterman, Jr.

They were the proto-collectors.

With 21st century hindsight, we can now fully appreciate the simplicity, originality, imagination, and creativity of these early automobiles. Kirk Gibson and George Waterman saved irreplaceable examples of automotive history that today reside in the Smithsonian Institution, the Henry Ford, and the Simeone Foundation, as well as several top-flight private collections.

The boys grew up in Boston’s affluent suburbs and had family ties to New England’s commercial and intellectual aristocracy. Leveraging this network within Boston and Rhode Island, the two would poke through barns and carriage houses, and make casual inquiries among acquaintances. “Hey, I know where you can find a similar car” became a common refrain, and the two diligently pursued every lead. People happily transferred old cars from the back corners of old buildings to them for free or modest—even at the time—sums like five bucks (a little more than $80 today).

They diligently cultivated a network of like-minded acquaintances and wrote letters to individuals, particularly surviving racing drivers, seeking desirable cars and their whereabouts. In the process, they added many historic racing cars to their collection—preserving relics that otherwise almost certainly would have been lost to scrap drives.

Ever effective at cold-calling, the two had an important endorsement in their back pocket: Frank A. Taylor, curator of the Smithsonian’s Division of Engineering and later Director of the United States National Museum. Writing to several prominent individuals about their vehicles, Taylor vouched for Waterman and Gibson, and more than once this successfully helped the young men preserve a piece of history.

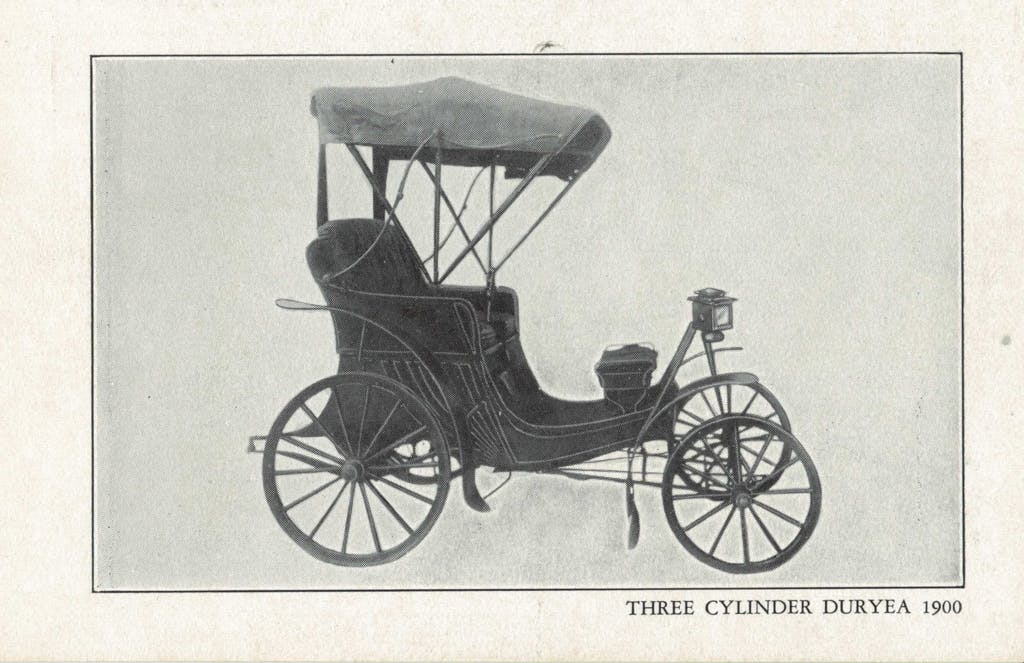

The resourceful duo’s mail campaign stands as their most creative effort at finding cars. The two printed pre-addressed penny postcards with pictures of old cars, distributed them to mail carriers around the Northeast, and asked them to put the cards in mailboxes around the region. If a farmer or estate caretaker knew of an old car, they could send details to Gibson and Waterman. The two would come calling, and if it met their standards, they would work out a deal to add it to their collection.

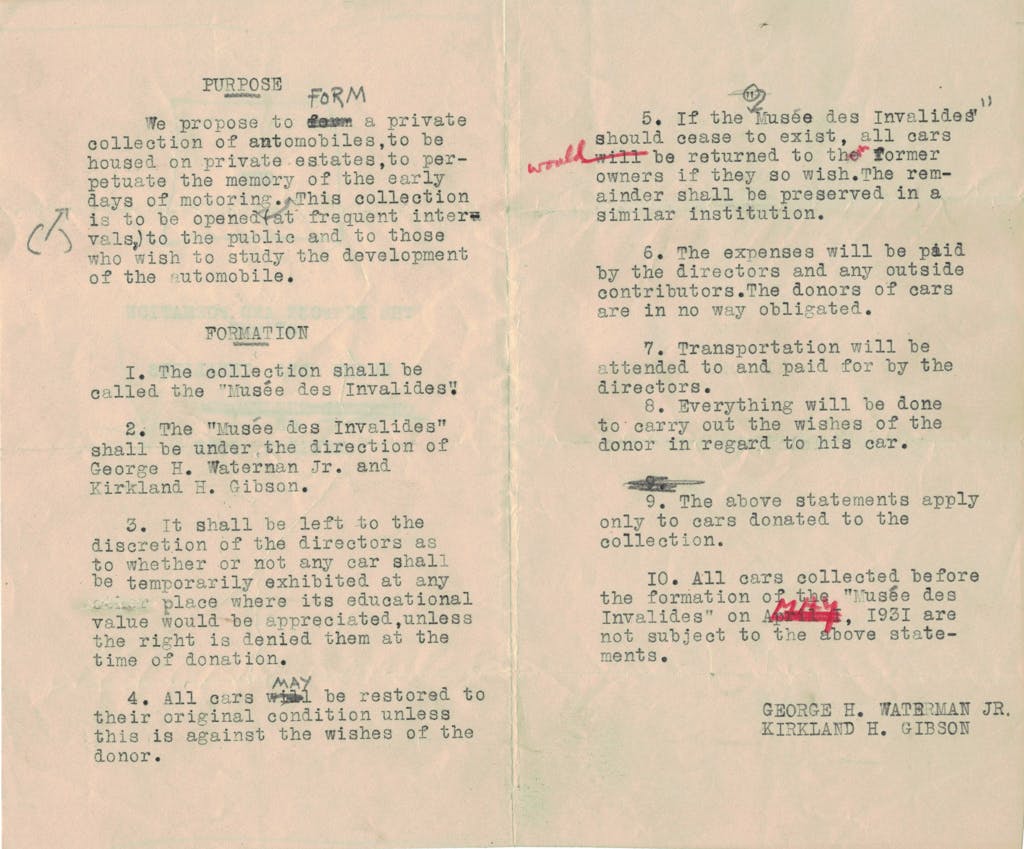

By the time they entered Harvard in 1931, Waterman and Gibson had a large enough collection to set about establishing their own museum. Musée des Invalides seemed an accurate working title, but upon reflecting that they might actually want people to visit the museum, they soon changed the name to the Musée des Vénérables.

By account of a 1931 inventory that included each vehicle’s cost (including transport), the collection numbered 42 vehicles. None were newer than 1913 (a FIAT), and the oldest was an 1896 Waverly. The most expensive were a $120 1900 Mors (approximately $2,100 today), a $135 1901 De Dion ($2,300) and a $165 1903 Ford ($2,850). Eight had been gifted to them. The boys, now young men, would soon pursue more valuable, contemporary, but still historically important vehicles as well.

They enjoyed the support of their New England peers and more than a few in the automotive industry. When Harry K. Noyes, the Buick distributor for New England, moved his operation to a multi-story building closer to Boston in Arlington, he let the two use his original facility in Waltham as their first museum location.

By 1938, having dropped the French title and now known as the Boston Museum of Automotive Conveyance, the Waterman-Gibson collection burgeoned to over 100 cars. Monumental brands shared space with more pedestrian manufacturers and companies that didn’t survive—if they made a relevant automobile, Waterman and Gibson sought them out. Isotta-Fraschini, Simplex Crane (the two managed to secure a pair from the Rockefellers) and Benz shared space with Fiat, Stanley, Locomobile, and even the White steam car used by President Taft. In a time when almost no one else looked back on the progression of the automobile, Waterman and Gibson created a physical encyclopedia of the first generation of automotive history. The collection included most of the marques that defined the automobile’s evolution in its first three decades.

In so doing, they had outgrown Harry Noyes’ old Buick garage in Waltham and were forced to store cars in several locations around the Boston area. Wanting to bring their collection under one roof, in 1941 Waterman and Gibson conceived their most audacious plan.

In concert with Thomas McKean, Jr., who at the time had a collection of some 25 cars and a notable accumulation of automobile literature, they purchased “Belcourt”(now a National Historic Landmark), an 1890s mansion built for Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont on Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island. Like his father, August Belmont (for whom the Belmont Stakes Triple Crown race is named), horses and carriages defined O.H.P Belmont’s interests. Architect Richard Morris Hunt created Belcourt’s purposeful essence as a stable and riding ring that happened to be attached to a luxurious residence.

Belcourt auspiciously held Rhode Island’s first automobile parade in 1899. It was the perfect backdrop for Waterman, Gibson, and McKean’s vision of a great automobile museum: covered spaces, elegant surroundings, and secluded storage in a setting complementary to the collection’s cars and memorabilia.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. The remaining aristocratic owners of property along Bellevue Avenue rebelled at the thought of a car museum attracting hordes of tourists to their midst. The three sold Belcourt in 1943.

Fortunately, their epic didn’t end with Belcourt’s sale. Gibson and Waterman expanded the breadth of their search for important relics of early automobile history and continued their efforts well into the postwar era. Their sleuthing never ceased to yield new relationships and opportunities to share unique automobiles—well-exhibited by Gibson’s chance intersection in with J. Frank Duryea, a pioneer of the American automobile in the 1890s and winner of the 1895 Chicago Times-Herald race, America’s first car race.

Gibson secured a Duryea Motor Wagon from a farm in Pennsylvania, and one of Duryea’s friends happened to notice it on the flatbed carrying it back to Waterman and Gibson’s facility. Cards were exchanged, and before the Motor Wagon was even unloaded the following morning, Frank Duryea and his wife Kathy arrived, armed with an offer. According to Gibson’s and Duryea’s accounts in the May/June 1996 issue of the Vintage Motor Car Club of America’s Bulb Horn, Duryea had been on the hunt for a Motor Wagon to drive in the 50th anniversary of the landmark race he had won years ago. Duryea said, “tell you what, leave it on the truck and deliver it to my place in Madison [Connecticut], and I’ll restore it for you if I can use it in the Times-Herald event.” Just like that, Gibson had a Duryea Motor Wagon restored by its creator.

The car, one of only thirteen built, now resides at the Henry Ford in Detroit. So it goes with many Waterman-Gibson cars: once in varying states of neglect, they’re now frequently the centerpieces of collections in the United States and around the world. To this day, if a car passed through their stewardship, the market recognizes its value and significance.

Sales across the decades bear out the Waterman-Gibson provenance. At Sotheby’s auction of the Rick Carroll collection in May 1990, a former Kirk Gibson 1907 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost Tourer, serial number 60-553, sold for $2,255,000. The oldest Silver Ghost in private hands, it fetched 25 percent more than its high estimate in a collector car market that was in free-fall. More recently, last August at Bonhams Quail Lodge auction, a 1928 Mercedes-Benz S-Type Sports Tourer restored in the Sixties by Gus Reuter for Waterman-Gibson sold for $5,395,000. That hammer bid landed 22.5 percent above the pre-sale high estimate.

What started as two boys creatively seeking out forgotten cars became a saving grace of automotive history and helped define what marques and models collectors would value in subsequent decades. Waterman and Gibson may not hold the household-name status that fellow collectors like Briggs Cunningham once did, but their contribution is no less significant.