MGs, Minis, and Millennials: The next generation of Little British Car enthusiasts

I often try to reminisce about England in the 1950s and ’60s. Crisp autumn days in the Cotswolds. Narrow village lanes. Classic British motoring. The problem here is that I was born in Canada. In the mid-1990s. The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows defines this sort of sentiment: Anemoia (noun): Nostalgia for a time you’ve never known.

I belong to a group of young British motoring enthusiasts, and we know this feeling well.

The postwar period in England ushered in the development of small cars that perfectly paired man and machine. The liberty and optimism of this golden era were complemented by the handsome styling and reassuring handling afforded by Little British Cars (or LBCs)—chief among them, the droptop. The period marked the pinnacle of raw, tactile enjoyment that British auto manufacturing could provide, and starry-eyed enthusiasts have been chasing it ever since.

I purchased my blue 1976 MGB in 2014, when I was 19. It was my first car. Originally a Harvest Gold American-market car that had been imported to Canada, this repainted six-owner MG exemplifies the perseverance of British motoring. Locked at 38,609 miles, the odometer stopped working shortly after I bought the B. It’s a five-digit unit that I’m certain has rolled over once, if not twice. The British Leyland Baltimore Dealer business card I found under the ripped and sun-bleached seat, along with a New York State Parks ticket from 1998, alluded to the car’s history of constant use.

I’ve added another 30,000 miles, taking it from Toronto to Pittsburgh, Watkins Glen to Detroit, and Niagara Falls to northern Ontario. When I moved to Toronto from the sleepy suburbs and brought my MGB along with me, I thought I was surely the only person my age masochistic enough to strap on leather gloves and daily-drive a half-century-old oily death trap on some of the most treacherous highways in North America. As it turned out, I was wrong.

Engaging with the car scene on social media, I connected with an entire group of classic car owners who defy the stereotypes of the British car community. This group of millennials and Gen Zers spans North America, from my home in Toronto all the way to Los Angeles. And they don’t just own these old British cars—they drive the snot out of them. Why are a bunch of teens and twentysomethings suddenly so obsessed with an obscure era of obsolete British relics? I reached out to investigate, and a few of them agreed to meet to chat about it.

I arrived in my MGB and was soon joined by Jason DeFreitas in his MG Midget, Colin Doust in an Austin-Healey Sprite, and Josh Crawford with his Austin Mini. They arrived late, but only because they’d had to procure some oil for a top off. Which was fine, because it gave me time to tinker with my horn, which had stopped working. We are nothing if not immersed in the British car experience.

Unsurprisingly, one of the first topics was the reliability of our cars. Crawford, age 18, has had the most stereotypical experience. “My car has broken down dozens of times,” he said, undeterred. “But every time it breaks down, I end up learning something and am better prepared for when it breaks down next. It doesn’t stop me from going on long-distance trips.”

Jay Leno defined the classic British car zeitgeist in a single sentence when firing up Moss Motor’s experimental MGB on his web series Jay Leno’s Garage: “Oh, wow, it started!” Leno is no stranger to British automobiles, and in an episode last year, he got behind the wheel of one of his favorite cars of all time—an MGA—owned and restored by 24-year-old enthusiast Daniel Harrison. I got in touch with Daniel, who described the reliability of his 1958 MGA as nearly flawless, though he insists that maintaining these aging English contraptions isn’t always sunshine and rainbows. “Sometimes they’re extremely irritating and uncomfortable, and then occasionally you get a little golden nugget of an experience which sucks you right back in again.” Daniel’s YouTube channel “Limit 55” aims to demystify the classic car experience and portray the honest picture of owning and maintaining vintage cars.

Jason DeFreitas shared a similar sentiment on this double-edged-sword regarding his orange MG Midget. “With 65 horsepower and four gears, having your engine scream at 4500 rpm for an hour gets old. It has also taught me every possible way to get oil out of my driveway. But it is a riot to drive, handles like a go-kart, and makes all the right noises.”

It’s no secret that British cars have a famous reputation for their electrical gremlins and oil stains. The consensus among us was that these cars will always need attention— because they’re old, not because they’re British. There will always be surprises and sometimes even dark days, but their agricultural robustness and their simple serviceability have allowed them to stand the test of time. Ultimately, if you take care of these classics, they will take care of you. Having a roadside assistance plan doesn’t hurt, though.

Cars like the MGA and B, the Austin-Healey 100 and 3000, and various Triumphs defined the modern recipe of the nimble, front engine, rear-wheel-drive sports car. Despite their front-drive packaging, you could lump Minis in with them, too. That all of these cars were also affordable endeared them to millions of motorists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Minis, for example, are one of the world’s most popular classic cars. From 1959 to 2000, a mind-boggling 5.3 million were produced, six of which were used in the filming of the Mr. Bean series. MGBs also rank as one of the bestselling classics; from 1962 until 1980, MG produced over half a million of them, and it is estimated that upwards of 15 percent are still on the road today.

In addition to scoring historic victories at Le Mans, Monte Carlo, and the Nürburgring, the MGB was practical, economical, and affordable—the GT version was affectionately dubbed “the poor man’s Aston Martin.” I would put extra emphasis on the “poor” given that having roll-up windows was touted as a groundbreaking feature in sales brochures of the time. Other standard features included an ashtray and steel wheels. But novelty equipment wasn’t what sold these cars. The promise of pure joy sold them.

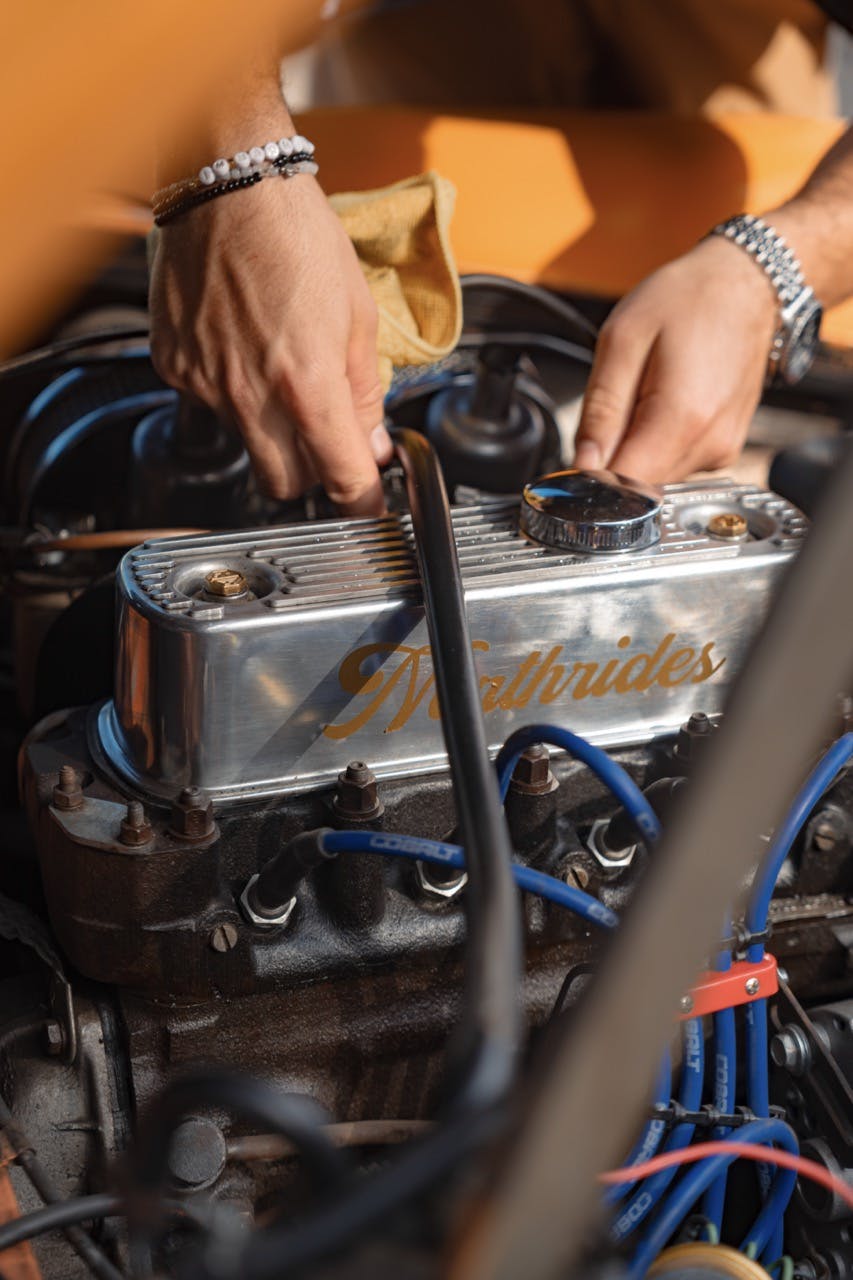

As demand for these Little British Cars wanes, however, so too does membership in many established classic car clubs. Although Colin, Daniel, and I are part of local and national Triumph and MG clubs, new memberships are still failing to offset the loss of old ones. Reassuringly, however, these cars are re-emerging in new circles. When he isn’t studying engineering, Josh can be found attending a number of local car meets and club events, including one at his university. Jason, meanwhile, runs a popular local car club called Northrides Orangeville. His aim is to create an inclusive group “free from idiots and judgmental a-holes” where his MG Midget can be seen alongside JDM classics and Kei trucks, German autobahn cruisers, and various exotics.

Today, the price of car ownership is skyrocketing. Many new vehicles feel out of reach for young people, and many of the previously sensible classics like Mazda Miatas and Datsun 240s are becoming all but unattainable. But not these Little British Cars. The value trend lines for MGAs and Bs, Midgets, Minis, and Spitfires have generally remained flat over the last decade. That’s great news for the money-strapped youth of the world.

Even better, these cars can be serviced and even rebuilt with the most rudimentary of hand tools. A half-inch wrench and a screwdriver can fix most things, and every single part for these cars is readily available—and largely affordable, though most parts seldom need replacing at all. In fact, the overall simplicity of these LBCs—MGB shock absorbers are based on 100-year-old compact hydraulic lever arms that can be serviced rather than replaced—helps keep more of them on the road. Putting miles on these cars comes easy when maintenance costs are low and fuel consumption is that of a lawnmower.

Even with fuel prices currently at obscene levels, I’m still not dissuaded from driving. My B averages 30 mpg on the highway, and I regularly exceed 6000 miles per year in it. Josh drives his Mini more than 2,400 miles a year; Jason takes his Midget on frequent long journeys; Daniel’s MGA has been across California and back; and Colin is planning a thousand-mile trip to Road America with his Sprite.

And even with their wallet-friendly powertrains, these cars are far from slow and boring, which only furthers their timeless appeal. Although the MGB’s 95 horsepower doesn’t sound like a lot, a properly tuned B-series motor is a highly capable musical instrument with a uniquely throaty howl. Mild upgrades to any of these cars—lightened flywheels, headers, shaved and ported cylinder heads—go a long way toward maximizing performance. Ancient, dependable, and famously fickle twin SU carburetors allow for some of the best throttle response available.

Sure, modern cars offer infinitely more comfort, safety, and even speed than their vintage British counterparts, which never got the memo on noise, vibration, and harshness. But the overwhelming majority of new vehicles today are a beige appeal to the lowest common denominator, each crammed with a tacky assortment of gimmicks which are simultaneously everything and nothing. Amid the landscape of increasingly boring modern cars and increasingly expensive classics, Little British Cars are a gleaming beacon of hope for a truly attainable driving experience. For younger enthusiasts, they present a unique opportunity to get the thrill of a sports car, the charm of a classic, and the price tag of a clapped-out Hyundai. And, as always, you won’t lack for attention: My 47-year-old MG gets looks everywhere I drive. Smiles and happy memories shared from silver-haired gentlemen recalling their youth. Waves from little kids on their bikes telling me to floor it (I usually already am).

“Still One Jump Ahead” read British Leyland’s MG advertisements throughout the 1970s. By the end of the decade, most new British cars were absolutely showing their age; they were outdated and outpaced by the competition, which increasingly came from Japan. Nevertheless, what made these British cars so popular in the past is what will allow them to prosper in the future. Affordability, simplicity, and fun have always been a recipe for success. Among the noise (and, increasingly, the EV hush) of today’s automotive landscape, cheerful LBCs will continue to attract the latest generation of enthusiasts eager to experience the analog freedom of the golden age of motoring. The Little British Car, it would seem, is still one jump ahead.

* * *

“What would you tell other people looking to get into a classic British car?”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Worked from 1966 to 1975 for British Car dealers and had lots of experience repairing MG, Austin’s, Austin Healeys, Triumphs, Jensen Healey, and of course any foreign car that came in. Those cars were made to drive for fun when the only American sports car was the Corvette. Funny, back then, was more into horsepower than motocross so was not interested in owning one of the British cars and stuck to big V-8s.

That has changed now and I would love to find a 1960 series British roadster to restore and drive and have fun with, driving and at car shows. Nice that so many have done this already.

Rtoyfor2, Have a 66 Spitfire in great shape for you. Owned it for last 20 years, but its time to find good owner for ” Baby”. Rpl333@gmail.com

I’ve been driving MGBs for over 53 years – mostly as “daily drivers.” My first one was a 68 in British Racing Green.

I lightly modified it to have narrow whitewalls (that was often a dealer upsell option back then), an 8-track tape player, and cruise control to save my right leg on my many 1,000-2,500 mile trips.

I currently own two: a relatively unmodified 73 chrome bumper project car and a highly‐modified, high‐performance 1978 MG MGB roadster.

Like many owners, I love working on them as much as I love driving them… and that’s a lot!

I live in Reno Nevada at an altitude of 4,631 feet and we are completely surrounded by mountains with steep winding roads up to 8,950 feet. These roads are perfect for our “Little British Cars.”

My 78 ZooooB has color‐matched painted bumpers and has been lowered 2-inches.

The engine has been bored, features 11:1 compression, has racing spec internals & fasteners, a crossflow head, dual Weber DCOE 45 carbs with 880 CFM of fuel‐air mixture, cold air intake, high‐lift & long‐dwell street/racing camshaft, special Davis Unified Ignition, LiveWires, Autolite racing plugs gapped at ⁵⁵/1,000ths, roller rockers, supplemental radiator and exhaust manifold cooling fans, flow through exhaust system.

The car has a rich custom interior in black with red piping, custom chrome window cranks, beautiful oversized burl shift knob, and real Rosewood dash appliqué, door cappings, speaker bezels, and door pull bases.

It has relays on all critical circuits and has many electrical additions and modifications with the 12-circuit fuse block relocated to the cockpit.

Its overdrive gearbox means I can take it on long highway trips without screaming gears and wear and tear on it.

For those interested, there’s a special ≈10,000 member worldwide Facebook group for owners who like to upgrade, modify, or customize their MGs – we have members with everything from pre‐war to the later models never sold in North America.

I’m Administrator of it – click the link, answer our questions, agree to the rules, and see all the thousands of modifications people from all over the world have made: the UK, US, Canada, Mexico, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Japan, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, and many other countries.

Barry Barnes, MG Aficionado & ‘Upgrading MGs’ Administrator

https://m.facebook.com/groups/4086226761

By the way, you’ll quickly learn there are several schools of Little British Car (LBC) owners:

1) Trailer Queen Purists – who restore or have their Little British Cars restored to factory originality, don’t drive their cars, haul them to car shows to be judged for perfection in restoration, and take a masochistic pleasure in how few points they fail to miss the magic perfect score; most Purists urge other owners to never, ever modify their car… often pointing out the superiority of their approach, shaming others for damaging an antique, and referring to themselves as “caretakers” rather than owners.

2) Driving Purists – similar to the above except that they are ocassionally willing to drive their near‐perfect cars to club meetings and car shows… taking a detail kit to restore them to perfection while there.

3). The “Normal LBC Owner” – who loves driving their Little British Car, keeps it in reasonable condition, isn’t compulsive about originality, has some rudimentary knowledge about it, can fix minor things, usually has a local shop maintain it for anything the least bit serious, is constantly learning more about its mechanical attributes, and details it two or three times a year. If they even notice Purists, they’ll probably shake their heads and think instead about the next issue they want to address.

4) The Self‐Taught Maintainer – who may or may not have known anything about auto mechanics before owning their LBC and who – through either necessity or curiosity – adds the joy of “wrenching” to the excitement of driving; these people often are likely to start making minor repairs and modifications… proceeding over time to such things as helping rebuild their engine or making other big upgrades. They, too, are unlikely to notice Purists, there’s so many issues they want to address.

5) The Driven Modifier – people who have a constantly evolving vision of what their British car should’ve been and could yet be. They tend to experiment with options to significantly beef up engine power, modify the electrical systems, doll up the interior, try out different tires and wheels, want to swap out the transmission, and such. They are likely to suffer from CES (Creeping Elegance Syndrome) and usually quickly forgive themselves for the additional time and money this involves. They view Purists puzzledly as nosy busy bodies… after all, they know they own their car and, as such, can do anything they wish with it

6) The Compulsive Customizer – these are the “edge pushers” who have developed advanced mechanical skills. They may have progressed through the Driven Modifier stage to the point of swapping out to very high‐performance engines ranging from Miata or Honda “four bangers” up through various imports, the Ford 302, a small block Chevy, a Chrysler Hemi or more; they often change the entire drivetrain, flare their wheel wells, and install oversized tires. For them, there isn’t anything they won’t consider. If they notice Purists at all, they view them with a puzzled curiosity… and quickly get back to their modifications.

Seems accurate. I’d classify myself somewhere between 4 and 5

Had my AH Bugeye for 28 years, absolutely loved “Limey”. No engine work besides SU carb tuning. Drove over 20,000 miles in that time. Extremely basic systems, enjoyable to work on. Parts readily available locally in Atlanta area. Sold it to David Silverkleit, aka “Bugeye Guy” in Ct to make sure it would stay on the road for future owners.

I converted my 77 MGB to a fuel injected 3.4 Chevy V6 and a T5 gearbox. It looks identical to stock from the outside but now has more than twice the power of the original engine and is a hoot to drive. At age 80 I still get under it to change oil, check trans and axle fluids, grease kingpins, etc. I’ll be driving it until the Dr. says I can’t. Then it’s my son’s.

A very good swap option for these cars!

His aim is to create an inclusive group “free from idiots and judgmental a-holes” . Sounds like he ruled himself out of his own club….

I can put you in touch if you’d like an invite to the club 🙂

I bought a 72 MGB GT eight years ago for the princely sum of $3500 Cdn. After a bit of wrangling to get it reliable and improve it a little for my own tastes, I have since driven it 30,000 miles in the summers. It has been very reliable over that period and it puts a smile on my face every time. It is now insured with Hagerty for $26K. The next step is to finish the performance build on a 2.0l B engine and an O/D that’s been sitting on my garage floor for the past two years. My love affair with LBC’s has since expanded to include a Westfield Super Seven for mostly track use, and a pair of Lotus Europa projects that will one day become a driveable car. It good to see younger people get into these quirky but lovable cars. There will be quite a few coming on the market in the next few years as us old timers age out of the hobby. Great article, thank you! Keep them driving!

I had the joy of owning a 74 Jensen-Healy from 1976 to 1983. Sadly we see very few of them these days in the Northeast US. Besides the issues mentioned with other LBCs there is also the rust plague that they suffer from here

Great to read that this is going on! I own 2 MGBs (roadster and GT both ’67) as well as a Land Rover 109, and a Jaguar Mk. IX. Always worked on them myself. My advice from long experience is: learn how to do things properly. Most of the issues with these cars have been caused by people who did not know what they were doing working on them and screwing them up. There are actually very few inherent design or manufacture issues. Some of the things are subtle, like this example: MGB original radiators were a very high spec industrial core type, with a great ability to dump heat, but have often been replaced by inferior cores or units by people who didn’t notice the difference or were too cheap. Leading to cooling problems. Keeping original spec often will avoid problems caused by inferior uninformed repairs. Learning to understand and really KNOW the electrical systems, SU carbs, and the like are important to having a good experience. Being a perfectionist in your actions and repairs helps. Making any mods in a non-destructive way that can be easily un-done is something I’ve come to believe in. In addition, operator error has caused a lot of issues with these cars. For example, early MGB non-synchro on first gear gearboxes are nice to operate and last a long time IF YOU KNOW WHAT YOU ARE DOING. Learning all these things is good for you too, for me it’s led to all sorts of opportunities in the world. And lastly, modern cars suck! Electronics in cars sucks! E cars are not saving the planet, it’s a lie. Simple, old school is just better!

Go to http://www.barcboys.com if you want to feed your disease about earlier times. Our story started with watching the races through the streets of Watkins Glen in 1952 through Dave Nicholas winning SVRA driver of the year in 2022. You are on the right path. Joe

Thanks for sharing!

Old guy here. Absolutely loved your article. My girlfriend and I bought an MGA in high school. Then, before we’d both graduated from the University of Waterloo we’d managed to go through five MGB’s. Always broke. Drove all of them through the winters. Had studded tires and overdrive on the fifth B. Now at 75 years of age I have seven vehicles……… one of which is a steel dash 1967 MGB GT. Trying to interest my grandchildren into driving something that has soul. You’ve also got a very entertaining writing style btw. Best, Rick Dow

Thanks Rick!

My first car was a 1951 MGTD. It was given to me (yeah, lucky me!) by my father who bought it in 1963 and gave me the key years later. As a kid we delivered newspapers on Sunday mornings as Dad drove I threw them out with the top down. What a cool car it was with styling much older than it’s years it turned heads everywhere.

I drove it for many years and went on to buy another ’51 which I restored ground up, with an MGA rear end and converted to wire wheels and discs up front. The new ratio really improved drive ability. Should have kept that one…

My current LBC is a ’64 MGB which saw some rust repair in the battery supports turn into fender repairs and floorboard replacement. A Moss supercharger was installed, new upholstery, canvas top, paint, etc, etc.. With a mild cam upgrade the supercharger really transformed this car.

The beauty of these cars is they were built for the average person to maintain with detailed manuals written in simple language.

It’s unusual to spot an LBC on the road but they used to be everywhere sputtering around, waving at each other.

I am heartened to hear that there is some youthful enthusiasm to keep these cars moving.