Legends of the GT350H: Fact, fiction, and Hertz’s “Rent-A-Racer”

Legends often contain, at their root, some kernel of truth. Take the GT350H—the Hertz rental special based on Shelby’s high-performance Mustang. To this day, people pass around wild stories of cars that were rented and had roll bars tack welded in for a day’s racing or had their potent HiPo 289s pulled and replaced with low-compression V-8s. These stories range from the sublime to the downright ridiculous, but each of these tall tales invariably ends with the car returning on Monday morning to the rental counter with the Hertz lady none the wiser.

If our “kernel of truth” hypothesis is correct, however, might there be something real at the heart of these myths? Perhaps even something that can be proved?

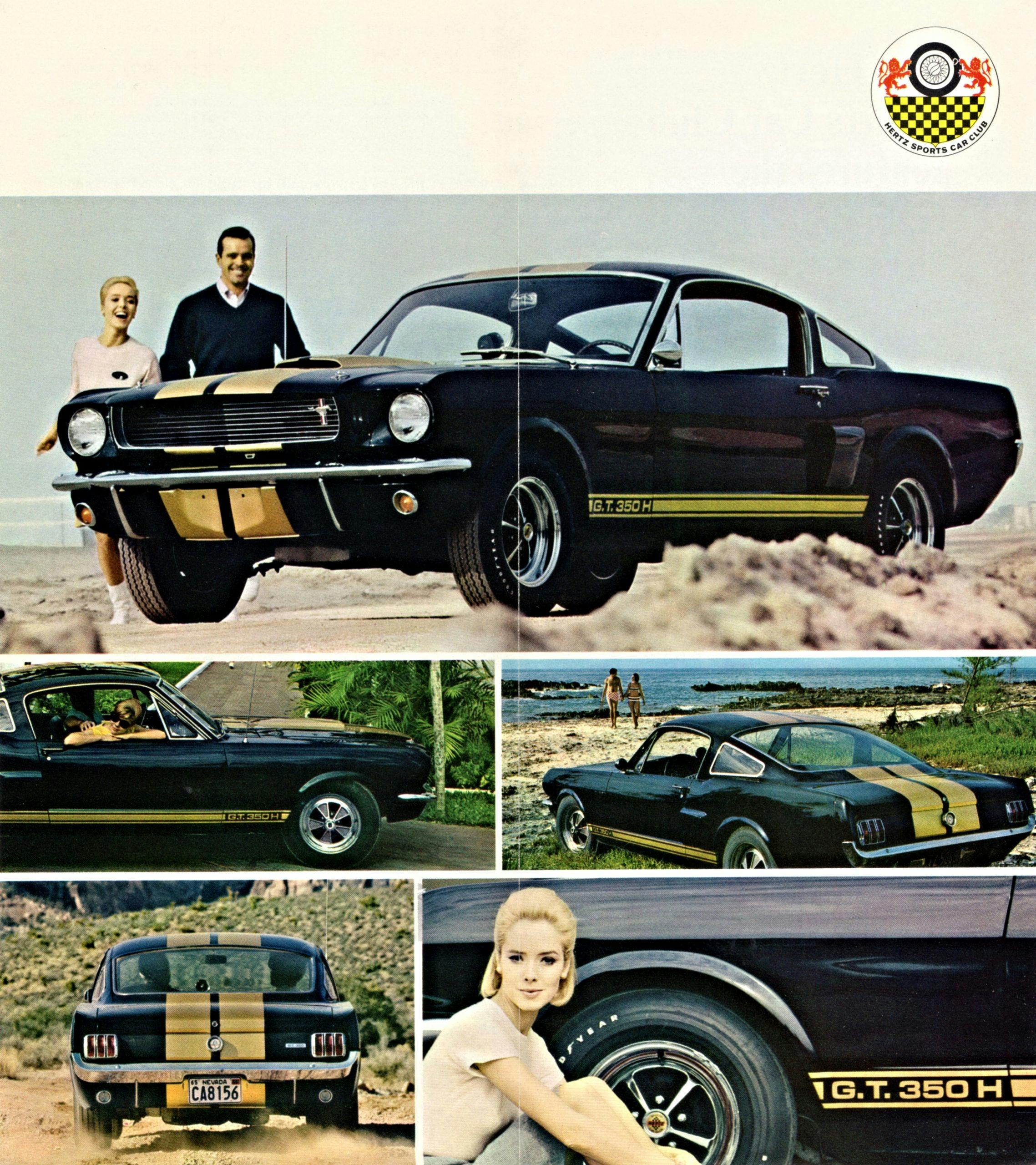

Before firing up the heavy excavation equipment in search of said murky roots, it would be best to recap of the foundation of the GT350H narrative. Once we’ve established the basic, documented facts of the famous rental machine, it will be much easier to home in on the many myths, misconceptions, and downright untruths. (Spoiler alert: They were not all black with gold stripes, nor did they all have automatic transmissions.)

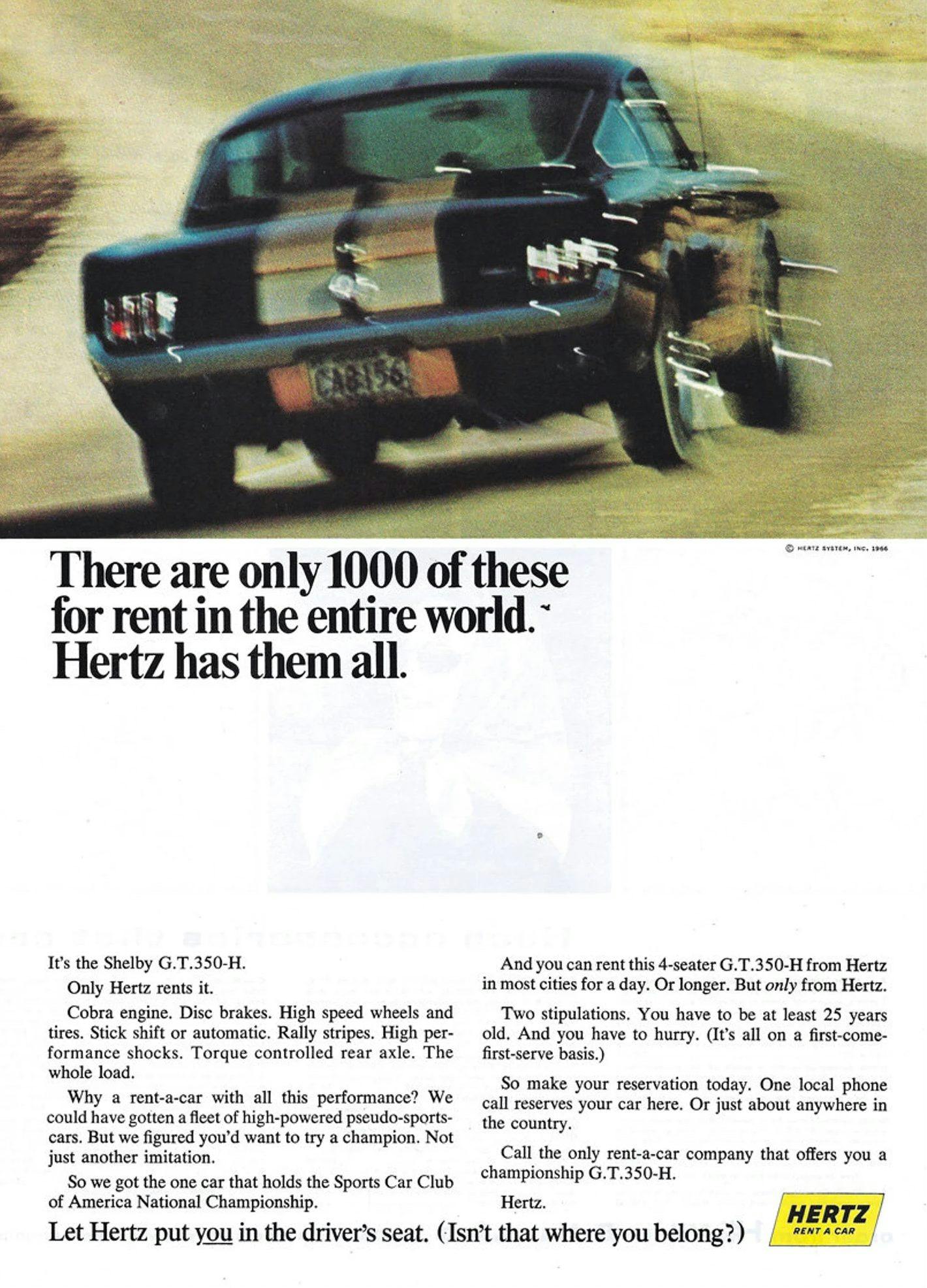

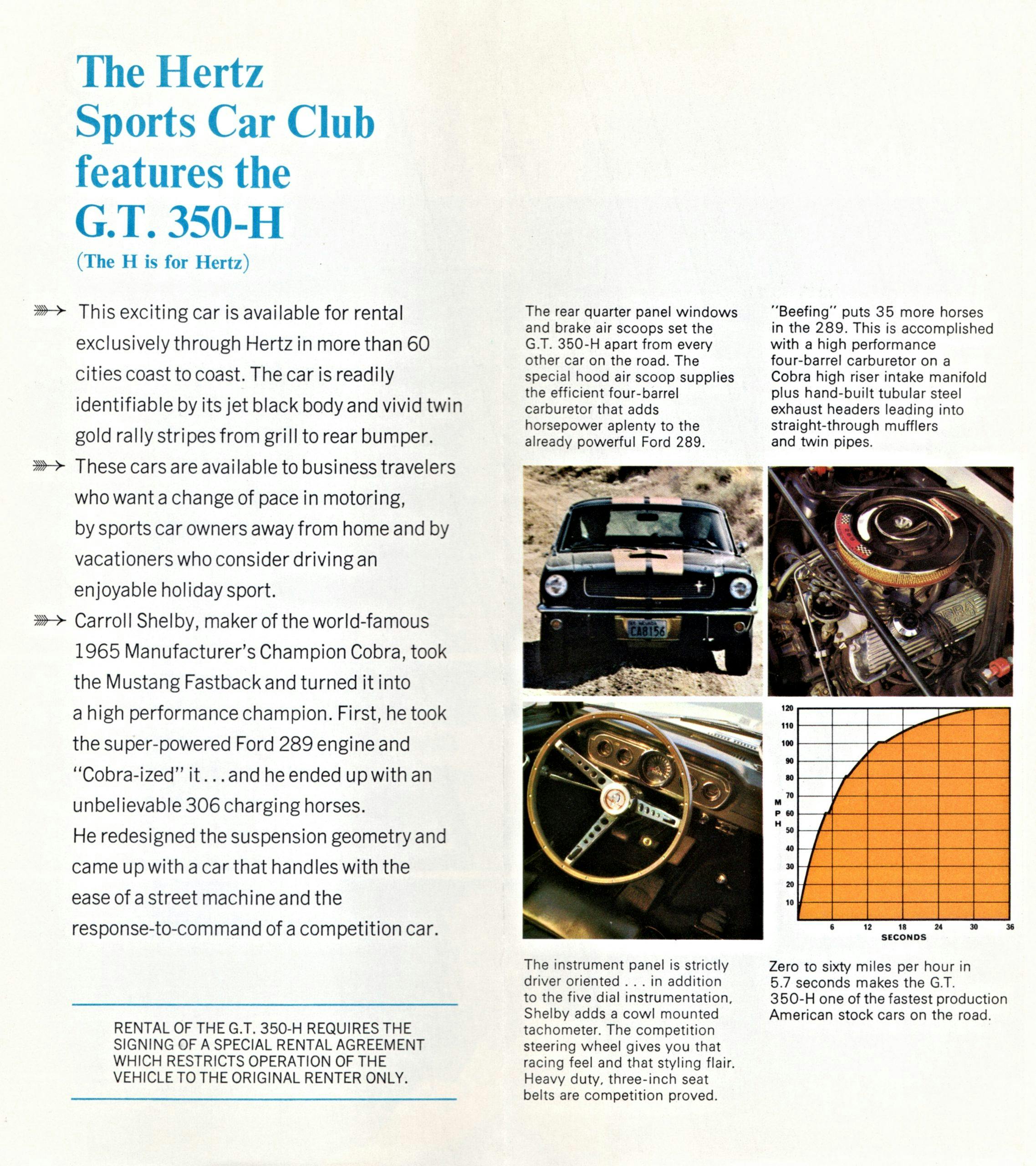

The idea of the 1966 Shelby GT350H “rent-a-racer” (a moniker never used back in the day) was born in the fall of 1965. Shelby American pitched the idea of, say, a hundred black-and-gold GT350s (Hertz’s corporate colors) that would provide a four-seat sports car component to Hertz’s less-than-financially-successful Sports Car Club. Shelby American talked up this benefit to Hertz as a selling point of the proposed program, but the sales pitch was not a case of corporate magnanimity; Shelby, too, would reap some substantial benefits.

Firstly, the deal would provide the instant gratification that comes with a guaranteed sale of a large block of cars. In the longer run, it would give the GT350 a huge increase in customer exposure, courtesy of Hertz. No longer would GT350 test drives be limited to the relatively scant Shelby dealer network but could be had at literally any major airport across the United States. Hertz bought the idea (both figuratively and literally) and over the next few months, the purchase quantity rose steadily from 100 to 175, then to 200, then, finally, to 1000 cars.

Not just black and gold

The matter of the color that these cars would wear, however, when they emerged from 6501 West Imperial Highway, was somewhat more complicated.

It should come as little surprise that the paint scheme was a subject of interminable corporate vacillation. The idea that the GT350Hs (a designation materializing a couple of months after Shelby’s initial chat with Hertz) provided to the rental company would all wear black with gold stripes was settled upon while the expected volume was 100, 175, and then 200 cars. But when the contract was finalized for 1000 cars (on the first day of winter, 1966), Hertz had decided that the build would be equally split between the five colors Shelby offered on its retail 1966 GT350s: Wimbledon White, Candy Apple Red, Ivy Green, Sapphire Blue and, of course, Raven Black. There was talk of some small quantity of white cars with blue stripes (and eventually, some actually delivered to Hertz) but it has never been clear whether this was a Hertz request or Shelby pushing the idea to expedite Hertz deliveries by using some of its already in-stock white/blue cars.

After some initial deliveries of black cars, instances of Hertz’s indecision began to surface with startling regularity. By the time the final GT350H was delivered to Hertz in May of 1966, the final tally reflected approximately 60 blue, 61 red, and 59 green cars being delivered with none of the reds and only a few of the greens having top stripes (all the blue ones had top stripes). And of the roughly 71 white cars, only the very early ones with blue side stripes (perhaps no more than two dozen, records aren’t clear) lacked top stripes. The cars without top stripes—the two, wide parallel stripes we call “Le Mans Stripes” today but in period were referred to as “rally(e) stripes”—were the result of a convergence of what color cars were being produced at the moment (itself a consequence of the shipment of colored batches of cars from Ford’s San Jose Assembly Plant to Shelby American) and whether Hertz had decided to stripe, or not to stripe, at that time.

Transmission and brakes

As for the often-misunderstood subject of transmissions, that one ended up pretty simple: Original plans for a 50/50 split between four-speed manuals and automatics morphed into all automatics after the first 85 four-speed cars hit the Hertz lots. If you count the initial prototype, a four-speed car that eventually made its way into the rental fleet, the total comes to 86 cars with that extra pedal on the left.

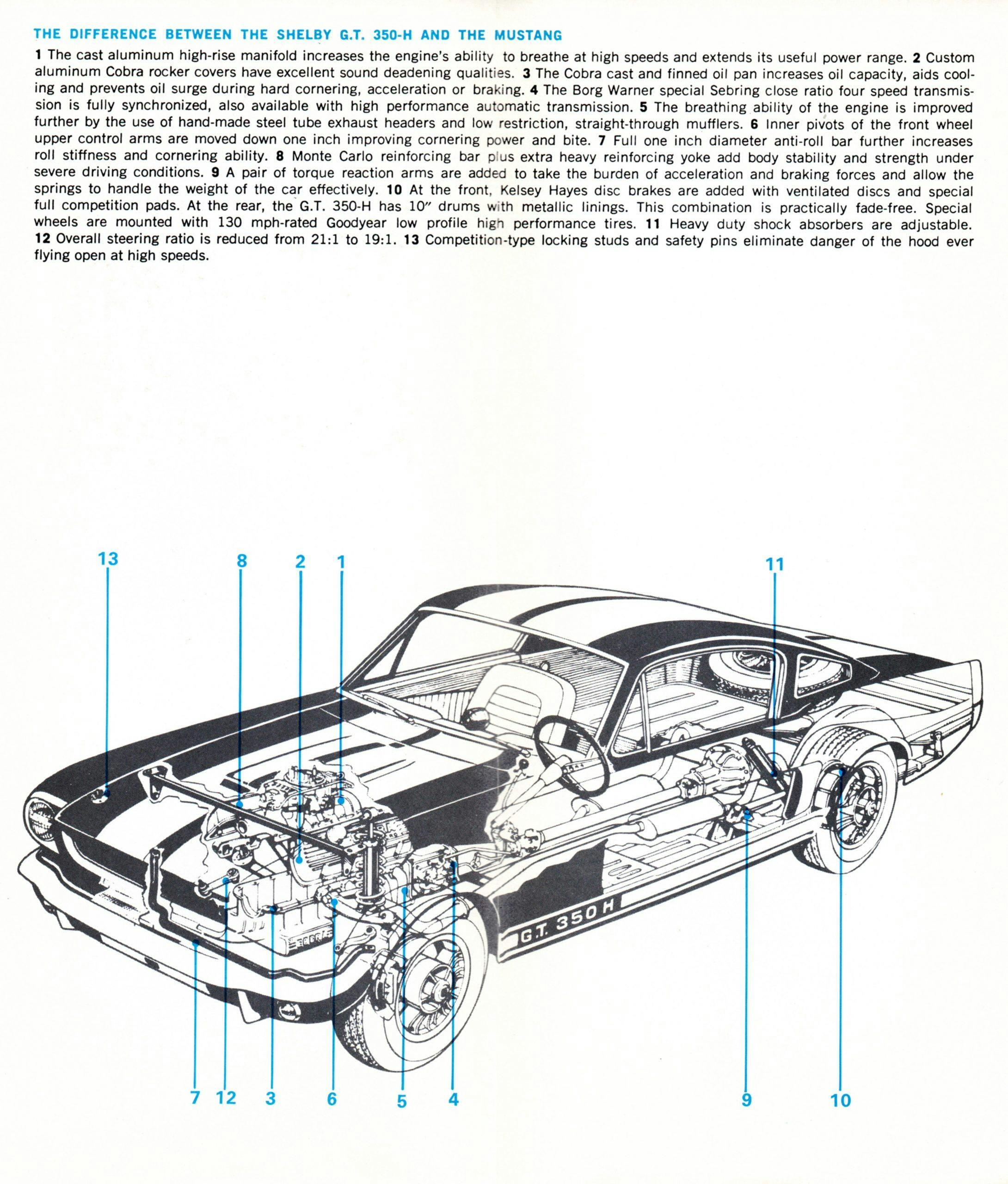

The subject of the brakes turned out to be anything but simple. Before any cars were produced, and just as the two corporations were ready to sign on the dotted line, Hertz hit Shelby American with a Lieutenant Columbo–esque “Oh, just one more thing … ” request: The cars would need to have power brakes, kicking off perhaps the largest fiasco of the whole collaboration. Had this come up a year later, it would have been a simple matter for Shelby American to phone San Jose and add power brakes to the cars destined for conversion to GT350H spec; at this time, however, Ford hadn’t yet certified power front disc brakes for production, which left Shelby American on its own.

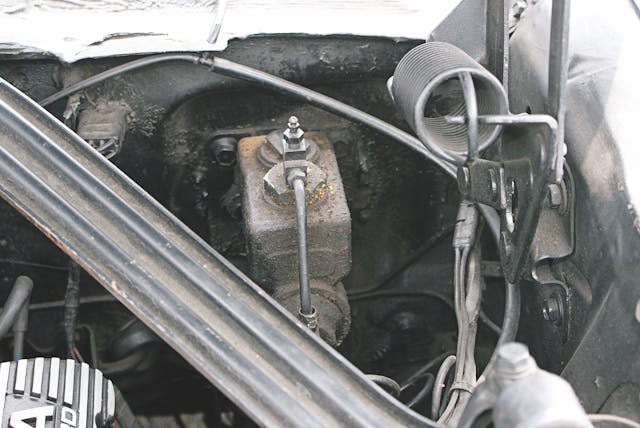

The solution was for Shelby to install the Minnesota Automotive (or, “MICO”) power brake master cylinder, a contraption invented to add brakes to farm implements that came equipped without them. It used a complicated “piston within a piston” arrangement to harness the pedal pressure applied to the piston to further assist that piston in providing more pressure and, therefore, more braking. One issue: Although the device did reduce the pedal pressure required, no two of the devices gave the same pedal feel. Even worse, as pedal pressure was applied and the boost kicked in, the brake pedal feel went from hard, to soft (as if the brakes just suddenly failed), then back to hard again. It was disconcerting, to say the least.

More of an issue, even, was that the Hertz fleet soon proved subject to an unexpected artifact of the GT350’s race-inspired lineage. In order for the legitimate racing GT350 to be legal in SCCA Production racing, there had to be some quantity of identically equipped machines produced for street use in the process known as “homologation.” The race GT350 (and therefore the street version, and by extension, the rental version) used metallic brake pads intended to provide repeated fade-resistant braking from high speeds. The downside was that they were notoriously non-functional at slow speeds until they got really warm. Hertz renters soon found that upon piloting their beautiful, black and gold fastback out of the rental lot, stepping on the brake pedal for the first time made it feel like the car was going faster!

When the issue was brought to Shelby American’s attention, it conducted repeated demonstrations for Hertz that showed, exactly as expected, that the GT350H needed the hard pads; after just two 100-0-mph stops, the Mustang’s standard asbestos pads faded away into oblivion. Of course, it completely escaped both parties that these cars would primarily be driven on city streets (not on Riverside’s or Willow Spring’s straightaways, where the demonstrations were conducted) and that the low-speed stopping provided by standard pads and shoes was simply more suitable.

In the end, the cars only received the standard brake fitment as they came out of service and headed for the resale market. All of their in-service rental time was spent with gold-foil stickers affixed to their dashboards warning that “This vehicle is equipped with competition brakes … heavier than normal brake pedal pressure may be required.” (After a few hundred cars were delivered with the troublesome MICO master cylinder, GT350Hs began rolling out the door—and stopping quite satisfactorily—with standard Ford master cylinders.)

The whole episode illustrated how the race-inspired GT350 was ultimately a poor match for Hertz’s “John Q. Public” rental clientele. In hindsight, it makes sense why the ’67 GT350H (and perhaps a hundred or even two additional ’66 cars) never materialized.

Rental-lot lore and autocross antics

Now that we’ve established a basis of fact, let’s move on to the matter at hand: the mythology of the abuse suffered by the Hertz “rent-a-racer” at the whims of Mario Andretti–wannabees.

Ford Motor Company itself was wary of the potential for renter abuse of the GT350H. In December of 1965, as negotiations between Shelby American and Hertz were ongoing, Ford evaluated a standard GT350 and determined that the Shelby rode a bit hard, was a little tough to steer, and took some effort to get stopped at low speeds (the first two not surprising at all, given the car’s character, and the third somewhat prophetic). One of Ford’s predictions, however, offered an early preview of a legend in the making: “Hertz may have a run on these cars on drag race night.”

In its endless retellings, the basic story of the GT350H goes that basically every one of the thousand-car fleet was rented and hit the track or strip, with Hertz totally oblivious to the shenanigans. It makes for a good tale, of course. In fact, one particular documented incident (among several definitive “kernels of truth”) paints Hertz not as a clueless dupe, but rather as a willing co-conspirator. A local sports car club was holding an autocross, which would be run in the parking lot of the Charleston, West Virginia Civic Center, followed the next day by a Concours d’ Elegance car show. The club president, a Cobra owner himself, approached the manager of the local Hertz office and asked if the company could be convinced to display one of its five GT350Hs at the club’s Concours. The answer was undoubtedly unexpected: Yes, but only if the Cobra owner would drive the GT350H in the autocross the day before! Arm sufficiently twisted, the club president skillfully piloted the Mustang through the cones on the day of the autocross. The club’s newsletter the next month reported that the car was a blast to drive, but, being much heavier than the sports cars against which it competed, was far from garnering any Fast Time of Day (FTD) honors.

Parts for the picking

Leo Levine’s The Dust and the Glory is undoubtedly one of the finest histories ever written about the Ford Motor Company in competition. In it we find a reference to another pervasive myth: that a Hertz rental GT350 had its engine removed and installed in a race car, in this case a Falcon being run in the 1967 Daytona 24 Hours. There weren’t many Falcons in that race, and decades after the incident occurred, the little Ford’s owner, the late Ray Heppenstall, was tracked down and queried about the incident. He stated that only the barest essence of the story was correct; yes, he did remove the engine from a GT350H and install it in his Falcon, but the Hertz car was, in fact, one that he purchased the year before after it was wrecked on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. A former rental GT350, yes, but not one in active service.

How about spinning another part-scrounging yarn? In 1966, Racer Tom Yeager had sold his Competition model GT350 (what we today call “R-Models”) and began running a notchback Mustang in the SCCA’s new Sedan/Trans-Am race series. Marlboro, Maryland, was one of those races at which, try as he (or rather, his mechanic, Tom Greatorex) may, Yeager could not get the Mustang’s carburetor dialed in. The solution lie under the hood of a shiny, black-and-gold GT350H sitting, unwatched, in the parking lot. It just so happened that the Hertz car used the same Holley carburetor as his Mustang. The device was surreptitiously swapped into the blue Mustang and, although Yeager didn’t win that competition, neither did he accumulate a distasteful “DNF.” After the race, Greatorex reinstalled the Hertz car’s carburetor and the incident was sure to be forgotten until it came out who had signed that GT350H’s rental contract: SCCA Director John Bishop! The Toms, Yeager and Greatorex, fessed up to Bishop and the threesome enjoyed a good laugh.

Then there was Long Island Cobra Racer Mel Wentzel who, lacking adequate vacation time, asked a friend to trailer his 289 Cobra to California for a race at Riverside Raceway. Upon arriving in the Golden State (via airliner), Wentzel and his mechanic checked in at Shelby American, only to find that their promised GT350 PR car had been claimed by high-ranking Ford executives attending the race. Shelby couldn’t make more press GT350s materialize out of thin air, but it could pull some strings with the local Hertz office, where Wentzel—despite being under Hertz’s 25-year-old age minimum—was able to rent a GT350H for the going rate of $17 a day plus $.17 a mile.

Why was it so important that Mel get a GT350 as his driver? Because aside from towing his Cobra and trailer, the rental car would serve as a convenient, emergency source of spare parts for the Cobra race car. Wentzel’s mechanic, upon finding the speedometer cable locked to the speedometer, removed the other end of the cable from the transmission and fabricated a plug to keep the fluid from being pumped out while they enjoyed the “free” mileage. How is it known that these events actually occurred? Because both Wentzel and his mechanic, Rick Kopec, (who, a decade after, would go on to found the Shelby American Automobile Club) say so … and have the pictures to prove it!

Whisper down the lane

What we’ve covered here are the best-documented examples of real-world escapades that resemble oft-repeated GT350H myths. In all likelihood, these “kernels of truth” are the foundation of some even taller GT350H tales. It is easy to see how just a dash of additional seasoning on relatively mundane events, in the form of extraordinary embellishments, could really spice up a story. We may never know the whole truth, so depending on whether you’re more of a romantic or a historian, the Hertz lore is both tantalizing and disappointing.

Made by myth?

You may be pondering whether documented “race history” of a given GT350H pushes its value above that of one of its “non-race” brethren. Frankly, it’s a moot point. In the incidents cited above—which are the best-documented cases in existence—none of the individual cars can be identified. More tangible is the significant effect we’ve seen that Hertz history has on GT350H values in general, the result of a dramatic about-face.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, when there was scant factory documentation yet discovered and all that existed was hearsay, rumor and innuendo, ex-Hertz GT350s represented, easily, 10 to 20 percent less value than a standard, same-year GT350. A big part of that was the mistaken belief that the Hertz cars were detuned. Consequently, owners of former rental cars went to great pains to deny or flat-out hide any vestige of the car’s rental history. Over the years, it became evident that these rental cars were mechanically identical to any other ’66 GT350 and, little by little, the values began to rise to equilibrium with, then eventually surpass, that of the un-Hertz fleet.

Today, the pendulum has swung in the exact opposite direction. Several classic and sports-car value guides rate the value of a former Hertz-rental GT350 as now 10 to 20 percent above that of a GT350 built for dealer sale. After all, a GT350H is a unique piece of the Shelby program’s history. Once that perspective became widely accepted, Hertz’s rent-a-racer got a well-deserved fresh lease on life.

***

Greg Kolasa is the Hertz Registrar (historian) for the Shelby American Automobile Club and is the co-author of several editions of SAAC’s World Registry. He is the author of the award-winning Definitive Shelby Mustang Guide, published by CarTech Books and the co-author, along with Shelby American GT350 Project Engineer Chuck Cantwell, of Shelby Mustang GT350: My Years Designing, Testing and Racing Carroll’s Legendary Mustangs, published by David Bull and also an award-winner. He has owned his black-and-gold GT350H since 1982. His better half, Carol, has owned one of the scarce red ones since a few years before that. The two Hertz veterans share their garage with an ex-Hertz 2006 Shelby GT-H.

In 1966 I rented a Blue n Gold for $17 a day. The three days I had it I beat the crap out of it in Phoenix Arizona. Had I only known then what they are worth today I`d had tried my best to own one. SO much fun ! Great memories ………………

I sure would Love to own a red or white one with a 4speed!

I turned 13 in 1966 and remember seeing the black/gold Shelby In the front row of the Hertz rental office. They had a white Mustang next to it but I have no idea if it was a Shelby. I was focused on the black & gold car

My friends older brother worked at the rental place prepping cars. The black/ gold Shelby disappeared by the end of summer. Rumor was going around about an engine swap. My friends older brother laughed and told us the car was in an accident and went to insurance salvage.