Media | Articles

Italian bikes are where deep passion meets engineering brilliance

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines the word “exotic” thusly: Introduced from another country: not native to the place where found. Strikingly, excitingly, or mysteriously different or unusual.

On these shores, in the land of Harley-Davidson, hamburgers, and Hee Haw, many of us grew up believing that anything that wasn’t of American origin was “foreign.” Repair shops that serviced these foreign makes were in nearly every town. Americans equated German motorcycles with function and dependability, Japanese motorcycles with being inexpensive and disposable, French motorcycles with being weird and wonderful, English motorcycles with being sensible and familiar, and Spanish motorcycles with being built of lesser quality materials and best suited for off-road usage. Italian motorcycles? The best of them fit the very definition of exotic. Each of the Italian manufacturers has demonstrated the creativity and ability to reach for the impossible at some time in their past.

Benelli

Benelli has given us a number of exciting and interesting models since its 1911 inception in Pesaro, Italy. The six Benelli brothers opened their first shop to repair and service motorcycles—just a few years later, they created their own engines and complete motorcycles. Their first exotic and groundbreaking design was the 175-cc overhead-cam single-cylinder racer by Giuseppe Benelli, which was raced by brother Tonino to four national championships before his death in 1937.

They also created a number of 250- and 500-cc machines in the 1930s, with the most innovative being the 250-cc short-stroke, double-overhead-cam four-cylinder that was supercharged and liquid cooled. It was faster in testing than its nearest competitor by 16 mph, giving the firm confidence that it was a world-beater. Unfortunately, with the war approaching, the engineers were forced to abandon the race department and move their efforts to wartime production of airplane parts. The motorcycles were disassembled and stashed during WWII.

After the war, priorities changed. Benelli found success throughout the 1950s and 1960s in selling lightweight motorcycles not only in Italy but around the globe. The motorcycles were sold in America through Montgomery Ward department stores as the Riverside 125-cc two-strokes and 250-cc four-strokes. In the mid-1960s, Benelli had the funds to again reach for the stars with 250-cc and 350-cc four-cylinder grand prix racers ridden by Renzo Pasolini, Kel Carruthers, and Jarno Saarinen. After winning two world championships, Benelli was developing a 250-cc V-8 before a Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) rule change rendered that idea a nonstarter.

After Benelli’s acquisition by Alejandro DeTomaso, the company soon offered the world’s first six-cylinder production motorcycles, the 750 Sei, and the smallest production four-cylinder, the 250 Quattro.

Bimota

High-quality components and advanced engineering have long been the hallmark of motorcycles produced by Bimota of Rimini, Italy. The name is derived from the first two letters of each of the three founders’ names: Valerio Bianchi, Giuseppe Morri, and Massimo Tamburini. Bimota began by offering frames that provided superior handling for the new generation of big Japanese four-cylinder engines. The company created a market for consumers who wanted bespoke exclusivity and craftsmanship that previously did not exist. Bimota’s high-water mark was the Tesi 1D of the 1990s, which featured hub-centered steering and mono-shock rear suspension, as well as a fuel-injected Ducati V-twin engine combined with an advanced alloy-plate frame. All this futurism came at a cost, as slow sales nearly bankrupted the company. Despite changes of ownership, a modern variant of the Tesi formula is still available in 2023, a testament to the dynamic design of the original.

Ducati

Ducati’s roots lie in electronics, as it began manufacturing radios and cameras in 1926, until its factory was flattened during the bombing raids by Allied forces in 1944. Soon after, the company started to manufacture a small pushrod single-cylinder engine that was developed by SIATA and launched its own version of the Cucciolo model in 1950. Not long afterward, Ducati hired Fabio Taglioni, who would go on to utilize the desmodromic valve system on Ducati’s newest model, the 100 Gran Sport. The desmo valve actuation was more precise than traditional springs, allowing for more radical cam timing and higher revs. Success in Italian road races led to higher sales in showrooms as hoped, and performance became an integral part of the Ducati story thereafter.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Fast, single-cylinder machines of 125-, 200-, 250-, and 350-cc followed, but the next big breakthrough came in 1972 with the launch of the 750SS, which won the Imola 200 race. Street models such as the round-case 750 Sport and then the square-case 750SS and 900SS models were strong sellers that offered the “race bike for the road” feeling for which Ducati was best known. In the next 10 years, Ducati embraced change and brought liquid cooling, floating disc brakes, trellis tubular frames, dry clutches, fuel injection, and multi-valve engines, such as the Desmoquattro, Ducati’s four-valve V-twin.

These innovations put Ducati back in the winner’s circle in World Superbike competition. The 851 and 888 models were winners, but the 916 was a tour de force in the styling department, too. Once Ducati had momentum, it was rarely off the podium and eventually returned to grand prix racing, scoring its first world championship in 2007 with Australian Casey Stoner piloting the Desmosedici racer. Ducati eventually offered the Desmosedici RR, a road bike with real grand prix–level performance that no other manufacturer dared to match. In 2022, Ducati achieved a long-held dream and won another Moto GP World Championship, this time with Italian rider Pecco Bagnaia.

Gilera

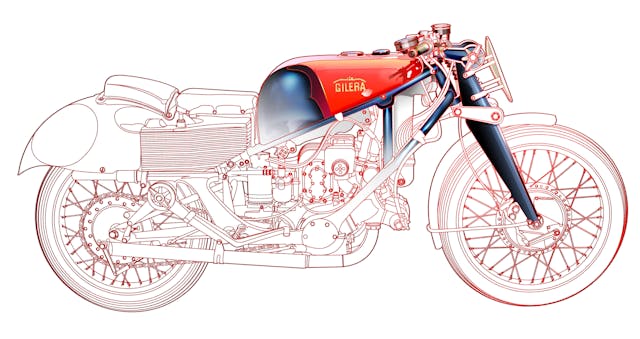

Arcore, near Milan, is the home of Gilera, founded in 1909. The firm acquired the Rondine transverse four-cylinder concept from designers Carlo Gianini and Piero Remor. This design reached its apex in 1939 with the use of water-cooling and supercharging to power the four-cylinder racer to a top speed of 140 mph and the European Championship.

After the war, with the supercharger ban in effect, Gilera redesigned the double-overhead-cam engine and frame design to score numerous grand prix victories and 500-cc world championships in 1950, 1952, 1953, 1954, 1955, and 1957, before withdrawing from the sport. With the sudden death of Ferruccio Gilera in 1957, founder Giuseppe lost some of his passion for the sport of motorcycle racing.

Gilera created some very worthy overhead-valve single-cylinder winners, such as the popular Saturno and Saturno San Remo, a works special. These motorcycles featured novel rear suspension, with horizontal springs and friction dampers. While not winners on the international stage, they fared well at the national level. Trying to cut costs, Gilera turned its back on four-cylinder racers and sold inexpensive 106-cc pushrod singles distributed through Sears Roebuck department stores in the U.S. In 1969, Piaggio Group bought Gilera. Today, Gilera is known more for urban scooters than motorcycles.

Laverda

Laverda, from the Breganze region in northern Italy, was founded in 1873 and produced agricultural equipment exclusively until 1949, when it built its first motorcycles. Following the lead of other ravaged postwar manufacturers, small-capacity machines built by Laverda competed in Italian road races such as the Giro d’Italia and the Milan-Taranto. Laverda built its first twin-cylinder engines in the late 1950s and continued on that path while increasing capacity, eventually leading to machines like the brutish 750 SFC in Laverda’s signature eyeball-searing orange. The most audacious design would be a result of competing in the Bol d’Or 24-hour endurance road race. Laverda stunned the world with the V-6 racer. Although it did not finish the race, it spoke well of the creative minds at work back at the race shop.

Moto Guzzi

Moto Guzzi was the only manufacturer to have its own wind tunnel for testing the aerodynamics of its motorcycles. That should come as no surprise, given the founder’s background in wartime aviation. Located in Mandello del Lario, Italy, the firm found success early with rugged designs that were fast and handled well. In the years after World War II, Moto Guzzi’s 250- and 350-cc racers won eight world titles. It was the glamour bike of its era, the compact 500-cc V-8 designed by Giulio Carcano, however, that was the final statement in high tech. The teething problems would have been sorted, and the mighty V-8 would’ve enjoyed more success, but it arrived a little too late, as Guzzi withdrew from grand prix racing at the end of 1957. Moto Guzzi launched a transverse-mounted V-twin engine to power a series of sporting machines in the 1970s, such as the V7 and Le Mans models. These became the essence of nearly every successful Moto Guzzi in the years that followed.

MV Agusta

MV Agusta, created at the infancy of aviation, continues to this day in that capacity, building some of the world’s finest helicopters. However, it was the fire-engine red racing motorcycles that are perhaps the most successful of all the Italian exotics. The early adoption of the Gilera-Rondine transverse DOHC four-cylinder engine layout served the firm well in the 1950s. MV snatched up its first 500-cc world championship in 1956 and eventually scored 38 world championships before closing shop. Count Domenico Agusta ruled the two-wheeled world of racing much like his four-wheeled counterpart, Enzo Ferrari. Agusta did not suffer fools gladly. On the road, the count reluctantly agreed to sell the public motorcycles worthy of the MV name: the four-cylinder 600, 750 Sport, and 750 America. These hand-built machines were very costly, roughly three times the price of a Honda 750, and did not meet sales expectations to justify the effort.

Twenty years after the company ceased motorcycle production, it would make an astounding return under Cagiva ownership. The stellar 750F4 Oro, created by Massimo Tamburini, was the star of the Art of the Motorcycle exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in New York upon its debut in 1999. The motorcycle, crafted of CNC-milled alloys that were combined with carbon-fiber bodywork and four under-seat exhaust pipes, also boasted a Ferrari-tuned engine that did not disappoint.

Exotic? Si signore.

The Italians long delivered on that promise and they continue today, whether it’s in architecture, automobiles, fashion, furniture, or food. Their rich and diverse heritage compels them to design with the head and, most important, the heart. That strong emotional attachment, la passione, is in the culture’s DNA.

Motorcycles: Exotic Italians is one of 20 classes to be featured at the 2023 Greenwich Concours d’Elegance, on June 2–4, 2023. Download the 2023 Greenwich Concours d’Elegance event program to learn more about Sunday’s other featured classes, Saturday’s Concours de Sport, our judges, sponsors, nonprofit partners, 2022 winners and more!

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Ducati is easily the best known worldwide of these brands. I only knew a few of these.

These are actually the well known ones, along with the scooter kings Vespa and Lambretta. Oddball Italians include Maserati, a small company completely unrelated to the car company, Garelli, best known for Mopeds, Beta and SWM trials bike sand my favorite oddity, Morbidelli. The Morbidelli company makes woodworking machines as a day job and and in the 70s and 80s branched out to make 125cc and 250cc grand prix racers and won some championships. Then in the early 90s Morbidelli went off the deep end by building some V8 sport touring bikes that were supposed to sell for over $100,000 and included a crate to ship them back to Italy for servicing. Nobody bought them so the project was shelved and the two extant ones are in museums