In the Moment: The color of history, the history in color

Welcome to a regular feature we call In the Moment!

A while back, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our staff chat room. His descriptions of those photos were fun, so we started running them as columns on irregular Thursdays.

These days, Sam writes ITMs specifically for publication. Usually while drinking too much coffee and going rhetorical walkabout. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

***

This column is called In the Moment. If you have been paying attention, you know this space as a log of obsessions. And to paraphrase a Seinfeld character, I got a lotta obsessions for you people!

We have here discussed many things. Heroes! Legends! Fast cars of complexity and genius! But also the power of memory and the freedom of starting over. A man in a bathing suit on salt and motorcycle. The only airplane engine anyone remembers. And the strange and distant stories of the strange and distant era between the wars.

I can’t claim to know how my head works. What I do know is that I will always be—to paraphrase two other TV shows—enthralled with what we owe each other. How we parse our differences, and how they can be visible in something as ostensibly simple as a photograph of an old car.

Today’s iteration of this column is hung on another obsession. It also represents a slightly different approach to this space. Not least because I am lucky enough to have the freedom; the powers that be basically let me run this column as I please. (Nobody blinked late last year when I spat out 5000 words on an old genius F1 car and peppered the whole thing with mustache-eyebrow jokes. If that’s not proof, I don’t know what is.)

You know what else is luck? Photography. Even now, when cameras and editing software so often give results indistinguishable from magic. If I have learned one thing after years of working with pro shooters, it is that the difference between a good image and an insanely great one is mostly just recognizing when you are fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time.

Technical skill matters, yes. Composition is critical. But those have never been rare. Image creation really just comes down to a person with a vision. Someone who saw what others did not, or who simply had the foresight to be in a place where something worth seeing might happen.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, a founder of the French photo agency Magnum, called that “the decisive moment.” Using that term in a discussion of photography is hard cliché, but screw it, HCB was a boss.

Moving on! Twenty-four hours ago, my friend Carter Hendricks texted me an image. Carter is an Alfa Romeo guy. I worked for him, once. He loves history and stories. He sent me this photo:

The car in focus, number 18, is an Alfa Romeo Type 158—a prewar grand-prix car, a Formula 1 car before the sport wore that name. It is in Geneva, at the Grand Prix des Nations, in July of 1946. The driver, Jean-Pierre Wimille, is French.

Grand-prix racing in the late 1940s lived in a liminal space. Money was thin on the ground, and the cars themselves were mostly left over from the years before World War II. Weird time, many fascinating choices made under pressure. But that’s not what got my attention. The photographer’s style looked familiar.

I did some googling. That Geneva shot was taken by a British man named Louis Klemantaski. I should have known.

Lord, Klem was good. Just a staggering eye for humanity and tone. Wikipedia notes that he essentially “invented the art of motor racing photography.” The statement scans like exaggeration but is sky-blue true.

Racing photography is an odd business. The titans in the space basically make things up as they go along. For Klemantaski, that meant stuff like riding along in a 1000-mile, balls-out 1950s open-road race that regularly killed people, shooting the first images from a top-shelf racing car at speed. But also so much more. Into a space that had previously held little art, the dude simply cannoned great and deeply original work.

Klemantaski died in 2001. The grain of the man’s efforts has been stitched into my brain for as long as I can remember. Elementary school? Earlier? Dad had so many books. I have this vivid little memory of sitting at a desk in my parents’ house in the 1990s, maybe 13 years old, in front of a desktop PC the color of wallpaper paste, waiting for the modem to dial up. Then punching “Louis Klemantaski” into an America Online search.

So, yes, I’m a dork.

We knew that, though.

One photo in particular is quite famous, a cockpit exposure from the 1957 Mille, all greens and sunlight. That Alfa image, however, was shocking mostly because so little color photography exists from 1940s motorsport, from any photographer.

Color! I had almost forgotten he shot it.

At first, I thought the Alfa photo was hand-tinted, a black-and-white image with dyed color later painted in by hand. The glacial speeds of 1940s color film plus tack-sharp exposure and short depth of field in a blurred pan? Sticking the landing would have been almost impossible.

And yet. It’s real color. He was just that good. (Post-publication note: I’m now told it was Agfa color film with an ASA speed of 8. —SS)

At one point, while we were texting, Carter sent over a snippet from the Klemantaski Collection blog:

This is one of those rare Klemantaski color images from the prewar and immediate postwar years. Very few magazine publications were then able to print color, so it was a bit of wasted effort.

As Klemantaski said, every color shot from those years was one that could not be sold.

Then, because Carter is Carter, he began making sideways reference to Thomas Kuhn’s landmark 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. I didn’t even know who Kuhn was, but Carter does not reference things lightly, so I googled the name and ordered a copy. The book is essentially about how we invent the new in a world that doesn’t always demand it.

Carter kept texting:

What Kuhn talks about is how even new good ideas aren’t put into use until the old ideas simply can’t hold any more. Truth doesn’t cause revolutions—utility does. (Later, Foucault said it was politics.)

Carter is an extremely interesting guy. Our text chains always teach me stuff.

Point the second: Early Klemantaski color is cool as hell. So I dove into the Getty wire archive—this column’s traditional image source—and went looking for more.

Lord, it was fun. Some of what I found is below. The small-print captions beneath each photo are a light edit and/or factual correction of the captions from Getty’s system. Not all the photos are color; some are just Klemantaski being Klemantaski, an artist. Either way, I chose these images because they show the man at his best. Windows into deeply human moments.

There is no grand takeaway here, just a pause to note that obsessions can be, in so many cases, all that keep us going. Yours are almost certainly different from mine. Drop them into the comments, if you have a second. Tell me about the rabbit holes you fall down. I’m curious.

And now, on with the show!

***

Above: He built Cobras and the empire that gave Ford its first win at Le Mans. But everyone forgets Carroll Shelby was a driver first. Look at the cigarette in his mouth! The man knows he looks cool, and he knows that you know it.

This is 1955, from the public-road sports-car races in Torrey Pines, near San Diego. I love how the colors softly pop on the woman’s dress and those plaid shirts, how the shadows roll and fade.

Above: From the left seat with Collins again. Look at those mountains in the distance! Imagine the drop just over that rail!

The sedan ahead is a Mercedes 220A. Slow, not a lot of grip, a dowdy thing. And sliding, next to some tiny Italian jewel now almost certainly worth more than my house.

Imagine coming into this corner at full blammo, covered in bugs (look at the windscreen). Miles before you sleep. And only a few feet away, people are cheering.

Above: There is so much raw and dirty America in this picture of France that it hurts.

Briggs Cunningham was a stud. A proper example of what one should do with obscene wealth. He won the America’s Cup, he built his own car company, he took uncompetitive American cars to Le Mans because it seemed like the right thing to do. (Jim Glickenhaus is, in many ways, a modern Cunningham minus the boats.)

Above: A starting grid at the Nürburgring in ’57. Note the line of drivers across the track. When the flag drops, they will run over and leap into the cars.

The four machines closest to camera are Mercedes-Benz 300 SLs. Gullwings. Even a dull one is now worth seven figures.

The detail is incredible. Like all the squarish shots here, this was taken on medium-format film. Medium-format negatives are virtually the size of your palm. Film exposures are like digital-camera sensors, in that physical size is directly related to resolution. (The high-res scan of this image, too large to run here, is simply bonkers.)

Above: Handling education in a nutshell! The car in the front is in oversteer—rear tires sliding, the fronts with grip. The car behind is in driver-induced understeer—sliding fronts, rear wheels with grip.

The old line maintains that, while oversteer scares passengers, understeer scares drivers. An understeering car doesn’t want to turn. Oversteer is essentially turning too much. (Think about that for a second.)

Lotus Cortinas are famously loose little monkeys. Your narrator has wanted one since forever.

Above: Collins. Dapper chap. And then there was Enzo, looking thrilled as always.

Another medium-format negative. Not color, but the clarity and skin tones are remarkable.

Above: Again, not color, but magnificent in every way. One of the most English drivers in history, in a deeply English car, with that oh-so-English mustache. Art.

And that is not a long lens. He was close. A few feet away.

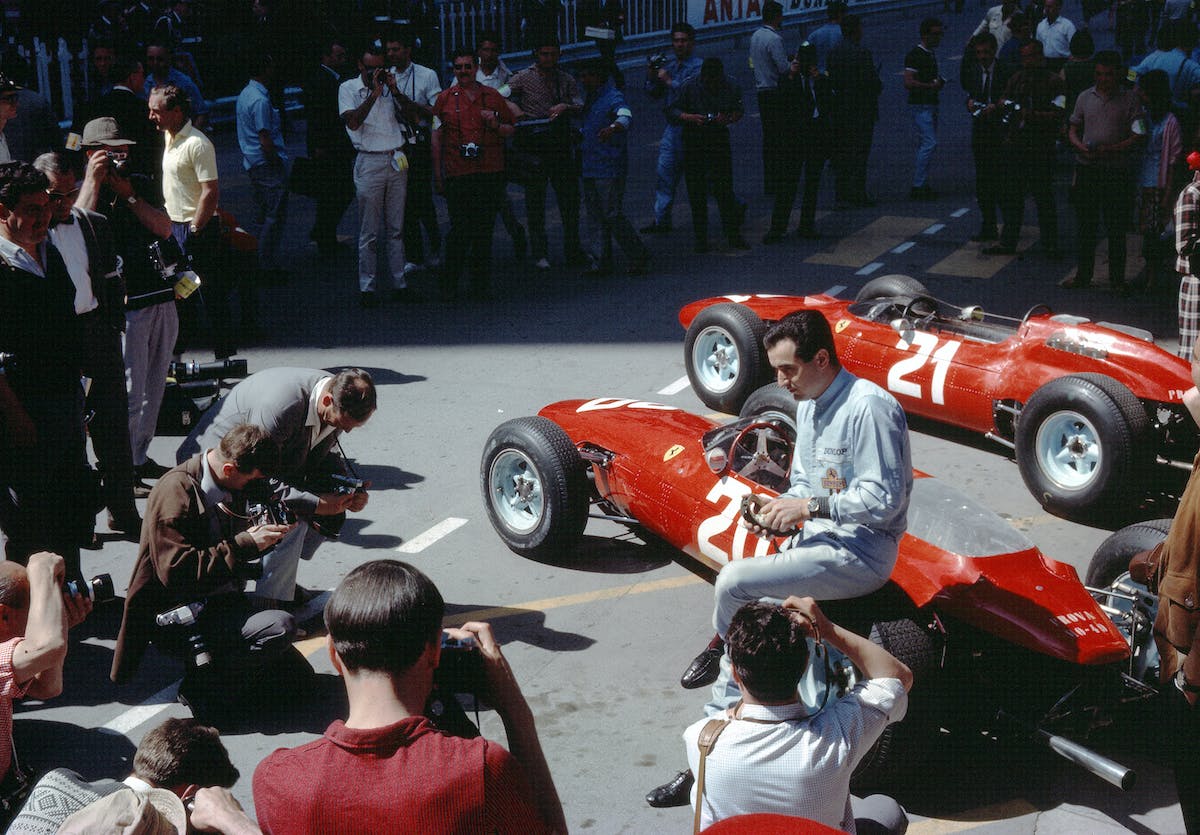

Above: A new Ferrari 156 in the old trackside pits at Monaco. The car they called “sharknose.” An elegant little thing in soft gloss.

No original 156s remain, though accurate replicas exist. Witness the center brace in that nose, the aluminum so thin, it has already been dented by rocks. Imagine the hours it took some Italian to form that shape by hand. The lens hasn’t distorted the shape—those intakes are asymmetrical.

Above: In the late 1950s, a wealthy American decided to take an American engine and some American hot-rod craftsmen to Formula 1. The cars were called Scarabs. The man, Lance Reventlow, was the son of American philanthropist Barbara Hutton and an heir to the Woolworth five-and-dime fortune.

If you do not know much about Scarabs, read this piece—the story is a bank of famous names, from Offenhauser to Phil Remington and Carroll Shelby.

They didn’t do well. It doesn’t matter.

Above: This is not technically a Klemantaski photograph. It was taken by a Swiss photographer named Yves Debraine but ended up in the Klemantaski collection. I am including it here simply because it is pleasant.

That’s the whole field in the 1959 Monaco Grand Prix! All of it!

So many hay bales.

Above: An F1 car being worked on in a Monaco gutter. On chocks, on wooden planks, off the back of a transporter.

That Maserati was driven by of one of the greatest drivers in history. He won the race that year.

The boards have cracks!

Look at the sidewalk. I wonder what is in those jugs.

Above: So much sweat. Innes is still in his race suit. His face says so much. He qualified seventh that year, out of 16 cars, but finished last, down 44 laps. That Lotus had mechanical problems; he ended up pushing it an entire lap. There is film.

He is in tennis shoes, I think.

Above: So much happening here. The narrow depth of field that just barely catches the back of Brabham’s body. Him leaning into that thin, high-backed seat. That enormous steering wheel. How the car was built by John Cooper, of Mini Cooper fame. And the meaning of that day.

Brabham was a legend. He won three Formula 1 driver’s championships, the last in 1966, when he was 40. In this photo, he is on the way to his first. That Cooper was the first mid-engine car to win an F1 title, but it would not be the last. The sport looked at the thing, noted its dominance, and basically threw all the old front-engine cars in the trash.

I met Brabham once, at the Goodwood Revival. He was charming, polite and mannered. I attempted to be polite. It was difficult, because I was speechless.

Above: Last one. The great man himself, Fangio. In that 250F Maser, the one from the boards and the gutter, on the way to a win.

Neat visual geometry. The car’s angle and the amount of tire smoke suggests a certain amount of . . . inertia. The drift must have begun in the middle of the corner.

I like to think that maybe—just maybe—he was having fun.

***

(Bonus gallery below, just because we can! If you have a minute, also try clicking the above images, to zoom in using our site’s “lightbox” viewer. Some are truly remarkable when scaled up. —Ed.)

What’s really amazing is that in those film days you had at best 2 or 3 chances to get the shot, and normally just one, unlike the dozens in our digital age. Not to mention except for some development magic there was no PhotoShop to fix it later. To get both the composition and technical perfection is Herculean. These photographers were unbelievable. Thanks for the reminder, Sam.

Sam Smith is a stud! Hagerty, you are lucky to have him.

Loved many of these. The Cortina’s, under steering and oversteering in the same corner, at the same time-wow.

Absolutely fabulous story and pictures! More please…Dr. John

Godhead. All of it, including the narration. And yessir, large-format negs are spectacular. My 1st race attendance was Torrey Pines, about 1957 at age 5 or 6, and I still recall being instantly smitten for motorsport – life-changing, forever-obsessed smitten – and a red 250TR that had red/white/blue bands around its nose. But maybe the best part is that the colors in these photos are the colors I remember when those times come to mind. Thank you!

Wonderful! I remember these cars as if it were yesterday. The feeling in the air was different. The cars of the late 50’s -60’s so graceful , beautiful. Thankyou for the photos.

Bravo!

Sam, what an incredible article. I spent an entire Saturday reading and clicking the links and reading more.

I’m gonna go back and read “With Moss in the Mille Miglia” again as you suggested and try to digest Jenk’s word more completely this time. btw I started this AM and it’s Dark now…

WOW!!

Its history in that instant. Many of us not having a opportunity to be there or that close would love to at least share in these moments with knowledge of how to acquire prints of the moments which mean the most to us but lack knowledge regarding acquisition of such special moments.

The cars bring back the memories of my old Scalextric race track set up in the basement of my youth. It was an early 60s set with a slick rubber track. The cars were a C54 Lotus, C55 Vanwall, C56 Lister Jaguar, and C57 Aston Martin. What a great memory you say. Nope, still have it all packed away in my adult basement.

Awesome collection of the Golden Age of racing!