In the mid-’50s, the Powell Brothers upcycled old Plymouths into some of the first SUVs

It’s tempting to think that upcycling and repurposing are new ideas, but the folks who lived through the privation of the Great Depression and then rationing during World War II might have a chuckle at that. It’s also tempting to think of the 1950s as a time of great growth of the middle class, and that’s probably true, but plenty of people were still pinching pennies in the ’50s with habits learned over the previous two decades of struggling. It was a time when Ford, Chevrolet, and Plymouth brands—which today we regard as solidly middle-class—were, in fact, regarded as “the low-priced three.”

Detroit automakers were making annual styling changes and piling on the fins and chrome, but some folks were still looking for a bargain.

In our article about Malcolm Bricklin and the origins of Subaru of America, the story mentioned that Bricklin’s relationship with Fuji Heavy Industries, Subaru’s parent, was established around importing the relatively sophisticated Rabbit Superflow S601 scooter, which had an automatic transmission and was a major improvement over Fuji’s first motor scooter, the S-1 Rabbit. That’s when I fell down the, ahem, rabbit hole that ended up at Powell Motors. Fuji Heavy Industries was a postwar offspring of Nakajima Aircraft. The peace treaties that Japan signed after surrendering prohibited the manufacture of military equipment, and Nakajima was repurposed, if you will, into providing badly needed transportation for civilians.

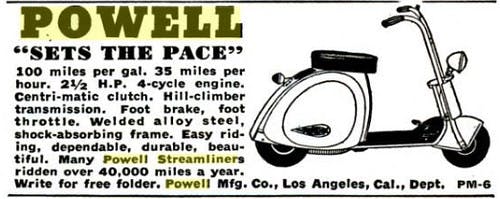

The S-1 Rabbit was relatively primitive, and the sources said that it was inspired by the military-issue scooters that American servicemen in the occupation forces used. While the better-known Cushman scooters supplied to the U.S. military were in part inspired Italy’s Vespa scooters, the original Rabbit was apparently inspired by GIs riding Powell Streamliner scooters in occupied Japan. Keeping with the repurposing theme, Fuji’s aircraft-building origins can be seen in the Rabbit’s front wheel, originally used as the tail landing gear for a Nakajima bomber. Unlike the Powell, which had a centrifugal clutch and a gas pedal, the Rabbit had hand controls for the throttle and clutch.

That brings us to entrepreneurs Hayward and Channing Powell. Right after graduating from Los Angeles’s Manual Arts High School in 1924, the brothers started their first company, Winner Radio, first producing relatively expensive radios before realizing that more economically-priced receivers would sell better. Apparently those didn’t sell that well either, as by 1926 the brothers established another startup called Powell Manufacturing Co., making battery eliminators (what we would call AC adapters) and table-top radios. The Powells’ electronics business lasted until 1932, and by the mid-1930s they were making motor scooters.

After supplying the military during World War II with the relatively primitive Streamliner out of their factory in Compton, in the postwar period the Powells manufactured scooters and then a light motorcycle that competed with the popular Mustang, made in nearby Glendale. When the Korean war broke out, they switched back to military production.

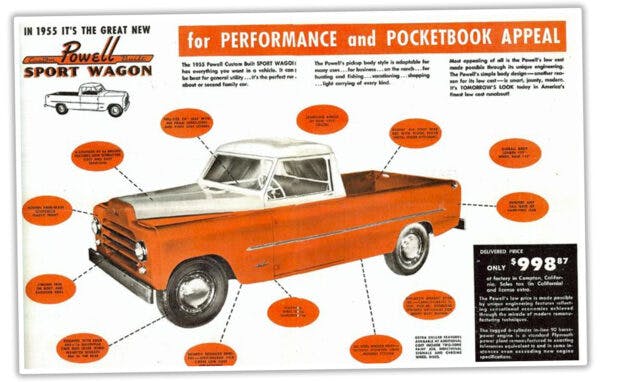

After the conflict in Korea ended, in 1954 the brothers decided to get into the four-wheeler business with the Powell Sports Wagon, a “sportsman’s car” available in station wagon and pickup truck formats. They ended up selling about 1200 “new” vehicles advertised as “America’s first car produced to sell below $1000,” and “Built like a battleship, drives like a sports car, rides like a sedan,” with a retail price of less than $1000 ($998.87 to be exact), compared to about $1700 for a new 1954 Plymouth Plaza. That thousand dollars works out to about $11,000 in 2023 dollars, or about half of what today’s cheapest vehicles cost.

How did the Powells do that?

By practicing repurposing on an industrial scale, that’s how. Under its new unified body, every Powell Sports Wagon was a 1941 Plymouth at heart. Well, not just the ’41, but rather a collection of Plymouth components. Perhaps the Powell brothers got the idea from southern California’s hot rodders, who were used to swapping engines and other major mechanical components, though in some ways it hearkened back to the early automotive era, when automakers assembled chassis for which coachbuilders added bodies.

The process started in an area of the Powells’ Compton, California, facility that looked more like a wrecking yard than an automotive assembly plant. Each 1941 Plymouth was stripped down to a bare chassis, and all unusable parts were scrapped. Today, a company would say “recycled.” The stripped chassis were inspected, aligned, and repainted, and all worn-out parts were replaced. Inline, flathead six-cylinder engines were sourced from Plymouths ranging in vintages from 1940–50. Channing Powell told Motor Trend, whose editor, Walt Woron, visited the brothers’ factory for a February 1956 article, that when choosing engines their concern wasn’t in the age of the engines but in their condition; they had strict limits on allowable bore wear, etc. Engines that passed inspection were then rebuilt and installed into the reconditioned chassis. You can see photos of the disassembly process and the rest of the Powell factory in this post on the Petersen Museum’s website.

The body’s styling, if you call it that, was in great part a result of the Powells wanting to avoid the cost of expensive tooling like stamping dies. There’s not a compound curve to be found back of the front fascia, which was fabricated out of fiberglass. Workers formed the rest of the body from heavy sheet steel, using brakes and simple bending fixtures. The result is a bit boxy, but the simple lines actually look a bit more modern to 21st-century eyes than the typical chrome-laden and overstyled American sedan of the mid ’50s, though the Powells did try to dress up the Sport Wagon with chrome window surrounds and some chrome trim on the vehicle’s flanks. One styling throwback, though, was the center-hinged hood. Like many of the panels, all the glass—including the windshield—was flat.

One novel feature was a sliding cylindrical drawer that retracted into the passenger side rear fender. As the Sport Wagon was pitched as a sportsman’s car, that drawer was suggested for storing fishing rods, though I assume a plumber or electrician could use them for small lengths of pipe or conduit. From the crimping on the end, it appears that the drawer’s housing may have been a piece of galvanized HVAC duct. On the pickups, the spare was stowed in a drawer under the bed, and some wagons had an additional bin that slid out of the rear bumper. Early models had bumpers and tailgates made of oak, later of steel. Customers could order diamond plate as an option.

Once formed, the body panels were placed in a jig and welded into a unified structure. In the case of the pickup, the bed was part of the body, like on the El Camino and Ranchero, not like a conventional pickup truck with a separate bed. After the body was mounted to the frame, it was painted in white, yellow, red, or green enamel and then baked. After final assembly, each car would get road tested for faults.

The interior was utilitarian, with vinyl-covered seats. A stock Plymouth instrument cluster sat behind a Plymouth steering wheel. The transmission was a column-shifted three-speed manual, also sourced from used Plymouths. The door latch mechanism was exposed on the simple interior door panel. As with any limited production vehicle, there are slight changes even within model years.

Woron put the Sport Wagon through a typical Motor Trend road test and came away mostly satisfied. He liked the small size and “easy steering.” Acceleration was described as “adequate,” and the brakes operated “smoothly.” Woron said that the Powell vehicle even held up on a backwoods trip he took.

Despite Motor Trend‘s praise, production of the Powell Sport Wagon only lasted another year. On the cover of that same Motor Trend issue was a Chevrolet Corvette. By the mid-1950s, despite the theoretical appeal of a “$1000 car,” American consumers wanted more than just cheap, basic transportation. It’s interesting that when Indian automaker Tata tried to hit a similar numerical target, a “one lakh car,” a car that could sell for just 100,000 rupees, Indian consumers rejected what was marketed as the cheapest car in the world. According to the Powell Sports Wagon Registry, 1020 pickups were made, along with 150 station wagons, of which only 11 are reported to still exist.

After the Powell brothers stopped making the Sport Wagon, they went back to making two-wheelers—in this case trail bikes—changed the company name to Powell Brothers, Inc., and moved from Compton to South Gate, California. Hayward Powell died in 1978, and with Channing Powell having already retired, the company officially went out of business in April 1979. Channing Powell died in 1988.

Of late there has been renewed interest in the Powell brothers and their $1000 car/truck. In 2020, Matchbox released a die cast model, and the Petersen Museum is crowd-funding the restoration of the very last Powell Sport Wagon pickup made. There is a community of Powell collectors and enthusiasts, and you can connect with them at the Powell Sports Wagon Registry.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Nice story. I like these orphan cars. The Powel, Davis, Kurtis and others that were only here for a short time.

I know the Jeepsters were flat sided as they used old presses for Refrigerators to press bodies post WW2 with the shortages of machinery. I wonder if the Powel flat sides has similar issues.

There are a lot of truckers and truck mechanics out there who will tell you that curved glass adds no measurable benefit to aerodynamics, it just makes windshields harder and more expensive to replace

Tell that to Chevrolet (Corvette) and Boeing and Paccar…

Not to take a thing away from the Powells, who done a great t’ing, but for “first SUV” you might want to peek in on the 1950 Studebaker Desert Explorer.

SUV is a marketing term for station wagon. While it’s true the earliest vehicles named Sport Utility Vehicle were based on a pickup chassis, the name is now applied to anything square with a lift gate. The term station wagon was keeping yuppies away in droves. But there is no difference. Front seats. Rear seats. Cargo area. Third row of seats at times. Some kind of a lift gate. People who would never buy a Station Wagon are on their 3rd or 4th SUV. This is what the world has come to. And you can have them in any color as long as it’s black, silver or white.

Sort of ironic that yuppies don’t like station wagons. The original station wagons were owned by affluent folks who needed to get themselves and their luggage to train stations.

I never heard of this one before. Pretty neat little truck.

Not sure about who had thr truely first SUV, but I know plymouth may have been the 1st to actually use the ferm “sport utility vehicle” in a magazine add in 1965 for the new Barracuda. A cross between a sporty car & the utility of the folding rear cargo/storage area.

I find it interesting that the Powell wagon has a plywood roof and the Powell truck has a plywood bed.