Media | Articles

If you enjoy fresh food, thank Frederick McKinley Jones (and a $6 bet)

Trucks are in the news these days. There are the oft-discussed supply chain issues, compounded by a national shortfall of about 80,000 truck drivers the industry would like to hire. Then there’s the “Freedom Convoy” of Canadian truckers who have been protesting pandemic restrictions for the past month or so. One manifestation of that protest on the Ambassador Bridge highlighted the movement of auto parts between Windsor, Ontario and Detroit,, forcing automakers to charter planes to ship parts and even cancel worker shifts. Overall, the stoppage of shipping on the bridge cost roughly $360 million in trade per day.

That immense figure emphasizes how dependent Canadians, Americans, and just about everyone else living in developed countries are on trucks delivering goods, namely food. While the “locavore” movement of eating locally raised food has grown, the vast majority of people in North America depend on food made many miles from their homes. Keeping that food fresh as it moves from farm and processors to market depends on refrigerated trucks and semi-trailers keeping it cold or frozen. About 75 percent of food consumed in America is transported by refrigerated trucks. Refrigerated trucks also carry temperature-sensitive consumer and industrial goods, flowers, and can be true lifesavers when transporting blood plasma and other medical supplies.

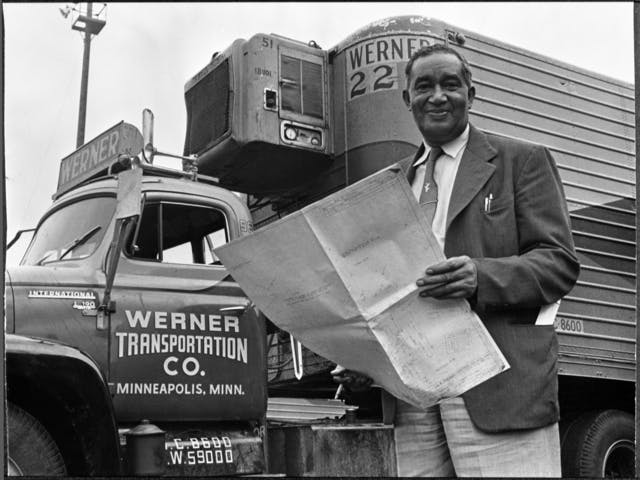

All of this was made possible by Frederick McKinley Jones, a prolific and eclectic inventor who was the first African American to be awarded the National Medal of Technology for his invention of refrigerated transport. He would go on to earn over 60 patents in a wide range of fields.

Jones’ life story could have been written by Horatio Alger. He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on May 17, 1893 to an Irish father and Black mother. While sources disagree on the exact details, he had a difficult childhood. One story has his mother deserting the family when he was young and that his father struggled as a single parent. A Catholic priest in Covington, Kentucky, adopted Jones at the age of seven and he lived in the church rectory until sixth grade, when he returned to Ohio as an eleven-year-old. Another story has his mother dying when he was nine, forcing Jones to drop out of school and live with the priest, who raised him until he was 16.

Whichever story is true, Jones did return to his hometown of Cincinnati, where he got a job at the R.C. Crothers Garage, starting either as a janitor or a mechanic’s helper. Jones was a hard worker who paid close attention to how the mechanics diagnosed and fixed cars. Virtually self-taught in a wide variety of disciplines, Jones was a genuine autodidact and polymath. He had an insatiable appetite for learning and a love of reading, and he absorbed everything he could about automobiles. Within three years of being hired as an unskilled laborer, Jones was the shop foreman. On the side he started building race cars and he is said to have made a name for himself around the Midwest as a skilled racer.

In 1912, Jones relocated to rural Hallock, Minnesota, where he got a job as a mechanic on a 50,000-acre farm. He would stay in Hallock for over 20 years, later describing the area as a place “where a man … [was] judged more on his character and ability than on the color of his skin.”

Hallock may have been relatively idyllic in terms of race relations, but a year after Jones moved to Minnesota Democrat Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as President of the United States. Wilson had been president of Princeton University in New Jersey but he was a southerner by birth and politics. Wilson made sure that the federal civil service and the military were racially segregated. When the U.S. entered World War I, Jones served overseas in an all-Black unit in France. His mechanical skills earned him a promotion to sergeant, first working as an electrician and later training soldiers in that relatively new technology. While in France, Jones rewired his army camp for electricity, telegraph, and telephone service, while also maintaining and servicing the base’s motor vehicles.

After discharge from the army, Jones returned to Hallock and his job as a mechanic. He continued learning about electronics on his own. Radio was young then and Jones taught himself enough to build the transmitter for Hallock’s first radio station. To earn spare funds in the winter when work on the farm slowed, Jones would also drive local doctors to house calls. When Minnesota snows proved too deep for his car, Jones acquired an old airplane fuselage, mounted skis on the undercarriage, and made a propellor-driven “snow machine” that was not unlike the first snow vehicle developed by J. Armand Bombardier, the creator of the snowmobile.

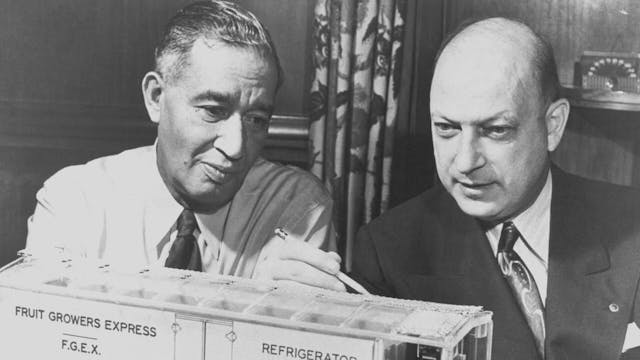

Prompted by one of the doctors complaints about sick patients needing to come in to his office for X-rays, Jones developed a portable X-ray machine that could be taken on house calls, though he failed to patent it—a problem he would rectify with later inventions. Based on his knowledge of audio circuits, Jones invented a system to synchronize sound with motion pictures. That invention supposedly caught the eye of Joseph Numero, a Minneapolis businessman who recognized Jones’ technical and creative abilities, though another account has Numero being impressed by the sound quality of the Hallock radio station. Whichever account is accurate, in 1927 Numero hired Jones to work on sound equipment for his company, Ultraphone Sound Systems Inc. (later Cinema Supplies Inc.), which manufactured public address systems for movie theaters in the midwest. Jones worked on improvements to picture quality and stability and patented a ticket dispensing machine for theaters, selling the rights to RCA.

Jones most important invention came as the result of a $6 bet during a game of golf, which Joe Numero liked to play. During a round with a foursome that included a friend in the trucking industry, one player complained that he had a contract to ship raw chickens from St. Paul to Chicago and that too many of the chickens were spoiling because the ice and salt they were using to cool the trucks didn’t last the trip. Numero bragged that he had an engineer on his staff that could solve that problem in 30 days. The trucking guy was skeptical, so they made a bet for $6.

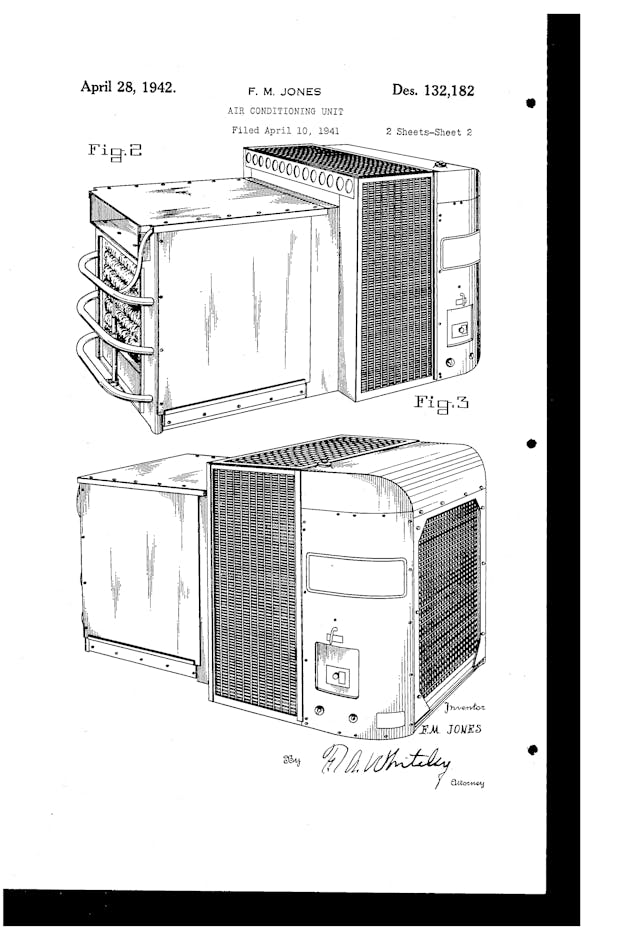

Numero went back to the office, told Jones about the bet, and the inventor proceeded to develop what became known as the Thermo Control Model A automatic truck refrigeration unit. Numero recognized the potential, so he sold off Cinema Supply to RCA and in 1938 he founded the U.S. Thermo Control Company. He made Jones the vice president of engineering—a lofty position far from common for a Black man at the time. A year later, Jones filed for his first patent on a transportation refrigeration unit.

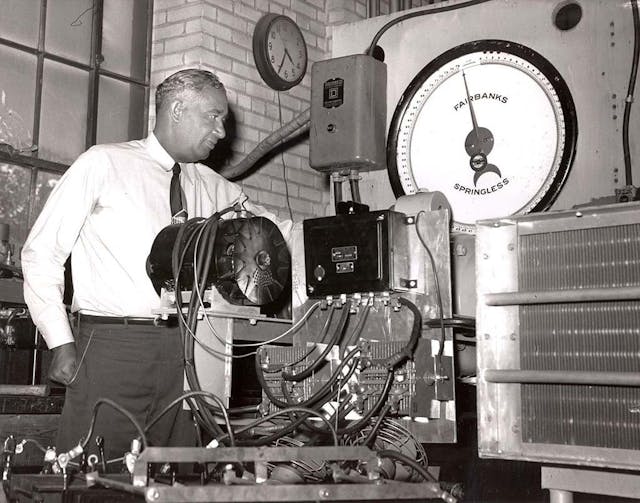

The Model A, which had an exterior compressor but placed the cooling tubes inside the trailer, worked fine as a proof-of-concept but it was bulky and very heavy—a consideration for truck operators concerned about fuel mileage. It also sat underneath the trailers or truck cargo holds, where it could collect dirt and road debris. The Model B was more compact but Jones had still not yet perfected the design. In late 1941, Thermo Control introduced Jone’s magnum opus, the Model C. It was self-contained, with a compressor, heat exchanger, and a one-cylinder Briggs and Stratton engine that could run when the truck’s engine was shut off. It was all mounted in a rigid, unitary metal body that mounted on the front of the trailer or cargo box, up where there was clean air for the heat exchanger.

The company was renamed to Thermo King in 1941. Jones, who had served with distinction in World War I, was 48 years old when the United States entered World War II. He may have been too old to enlist, but he served the war effort in his own way. For the duration of the war, Thermo King made Model C refrigeration units exclusively for the military, configured for use on trucks, boats, and airplanes to transport food and medical materials to soldiers on the fronts. Because the Model C was self-contained, portable units could be air-dropped into the field. Because of Frederick Jones, soldiers, sailors and airmen had cold water to drink, perishable food to eat, and therapeutic drugs and blood plasma in the event of injury or sickness. Jones’ units were also used to air-condition field hospitals, airplane cockpits, and to cool those planes’ engines.

After the war, the Model C was made commercially available and it had an impact well beyond the trucking industry. The change it effected on the agricultural and grocery industries was immediate and long-lasting, paving the way for the modern supermarket. It also changed the way people ate. Items that previously were only available as canned goods could now be purchased fresh or frozen. Clarence Birdseye had invented quick frozen foods in 1924, but getting them to market still frozen was an issue. Because of the Thermo King Model C, consumers could now buy produce “out of season” as it was shipped across the country from California or the South via truck and refrigerated rail cars, and a much wider selection of frozen foods was available. The impact of Jones’ invention was felt far beyond the continental United States. Thermo King units on ships and then airplanes made it possible for countries to ship their perishable crops to markets around the world.

By 1949, Thermo King was doing over $3 million a year of business and today it is more than a $150 million/year operation, part of the Trane family of HVAC companies.

Called “the man with a million ideas” and “the king of cool,” Frederick Jones was granted 61 patents in his lifetime. He died in 1961 of lung cancer and was posthumously awarded the National Medal of Technology in 1991, the first Black inventor to be so honored. In 2007 he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. The Thermo King Model C survived Jones, staying in service into the mid-1960s. The original Model C cooling unit actually still exists, on display at Thermo King’s Minneapolis headquarters.

The next time you sit down to a five-course meal with fresh meat and produce, or even just enjoy a slice of frozen pizza, thank Frederick McKinley Jones.