German regulators almost killed the original 911 Turbo’s whale-tail spoiler

Carmakers and regulators are involved in a continual, ever-evolving game of tug-of-war. Perhaps the biggest indication of this reality is the significant gap separating a car’s vision—put forth by OEM design and engineering departments—and the reality that government restrictions will permit. When regulation happens unexpectedly, automakers sometimes are forced to compromise in less-than-ideal fashion: the MG B’s rubber bumpers and the impact-absorbing blocks Lamborghini fitted to the Countach, for example.

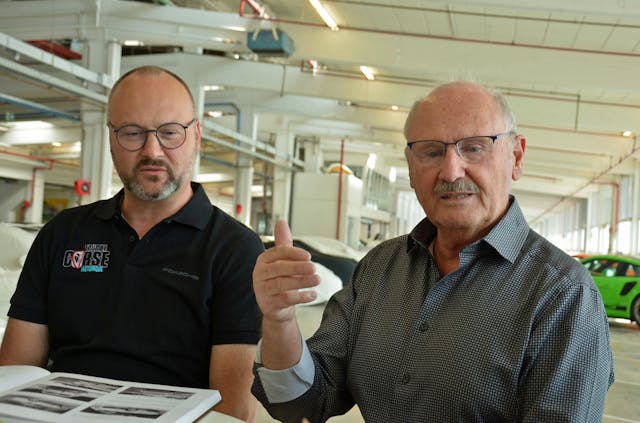

When German authorities tried to kill the original 911 Turbo’s spoiler, however, Porsche fought back—and won. We sat down with two former Porsche employees who remember the court battle to get the story.

Porsche first fitted a rear spoiler to the 911 when it unveiled the limited-edition Carrera RS 2.7 in 1972, and it’s this famous ducktail that has made a comeback several times since, most recently on the 2023 911 Sport Classic. We tend to take spoilers for granted in 2022; they’ve appeared on the humble Corolla and the brick-like Land Cruiser, not to mention everything in between, but they weren’t always ubiquitous. Spoilers and wings were nearly unheard of on street-legal cars five decades ago, and German authorities were caught completely off-guard by Porsche’s use of this racing-inspired innovation.

“[With the 911 Carrera 2.7 RS], the situation was so entirely new that the authorities didn’t know what to think of it, and Porsche only filed for a single approval of the ducktail. The authorities didn’t know how to respond [so they approved it],” Harm Lagaaij, Porsche’s former head of design, tells Hagerty.

Precisely 1580 examples of the 911 Carrera 2.7 RS were built, which isn’t exactly high volume model by any stretch of the imagination. The stakes increased when Porsche got moving on its much bigger plans for the 911 Turbo it aimed to release in 1975, when the ducktail morphed into the famous whale-tail. Let’s just say German authorities were not pleased to see yet another animalistic rear end in its homologation queue.

“We came with a new version and the authorities asked, ‘once more?’ We said, ‘why not? It’s good for aerodynamics,’ and they said ‘no,’” remembers Lagaaij.

Safety concerns were at the core of the problem.

“Authorities claimed that if the Porsche is stopped or moving slowly and a bicyclist hits it from behind, the rider might get hurt by hitting the spoiler,” explains Hermann Burst, who joined Porsche in 1969 to develop race cars (including the 917) and later worked on street-legal cars, like the 911 Carrera RS 2.7.

Porsche took these concerns seriously. It performed crash tests using dummies to verify the claims, and it even redesigned the spoiler with a rubber-like edge in a bid to get the green light for production.

None of these efforts changed the government’s position.

“The president of the highway authority said that he felt the upper edge of the spoiler was still very edgy, and he felt it was hard enough to break the arm or the ribs of a person hitting it,” Burst tells me.

Porsche pointed out that roof racks and ski racks also had sharp edges yet they were approved for road use, but its argument fell on deaf ears. Releasing the 911 Turbo without a spoiler was out of the question for Porsche; this was a functional piece essential to performance, not a superfluous, attention-seeking outgrowth of a designer’s imagination. The downforce it produced helped keep the rear end in contact with the pavement at high speeds.

Faced with no other option, Porsche sued the Federal Republic of Germany. Its defense team argued that the spoiler didn’t make the 911 Turbo more dangerous than a standard 911, and the arguments it presented were backed up by the opinion of a medical professor. The court agreed in Porsche’s favor. The memory of this triumph is enough to make Lagaaij smile today. He says that the automaker never ran into spoiler-related issues again.

“[The victory] meant that, once this particular spoiler was approved, the motorsport people could start asking for even bigger spoilers,” he says. “Which, of course, is precisely what happened,” he adds.

Porsche wasn’t the only company whose spoiler plans were nearly, uh, spoiled by regulations. BMW faced a similar problem with the aerodynamic package it made available for the E9-based 3.0 CSL. Rather than go to court, it cleverly delivered cars with the spoiler in the trunk rather than on the trunk lid. Buyers had to install it after taking delivery, so it wasn’t standard equipment and thus didn’t need to be approved.

Regulators aren’t going to stop regulating, of course. But once in a while, the right pair of scissors is all it takes to cut through the red tape.