75 years ago, U.S. troops liberated Volkswagen plant

While we battle through this cursed health situation, it’s important to remember that the human race has been through worse. Much worse. Seventy-five years ago, on April 11, 1945, U.S. troops liberated 7700 forced laborers at a war-torn Volkswagen plant in the city then known as Stadt des KdF-Wagens, or “City of the KdF car.”

Located on Germany’s Mittellandkanal (Midland Canal), Stadt des KdF-Wagens was later changed to Wolfsburg.

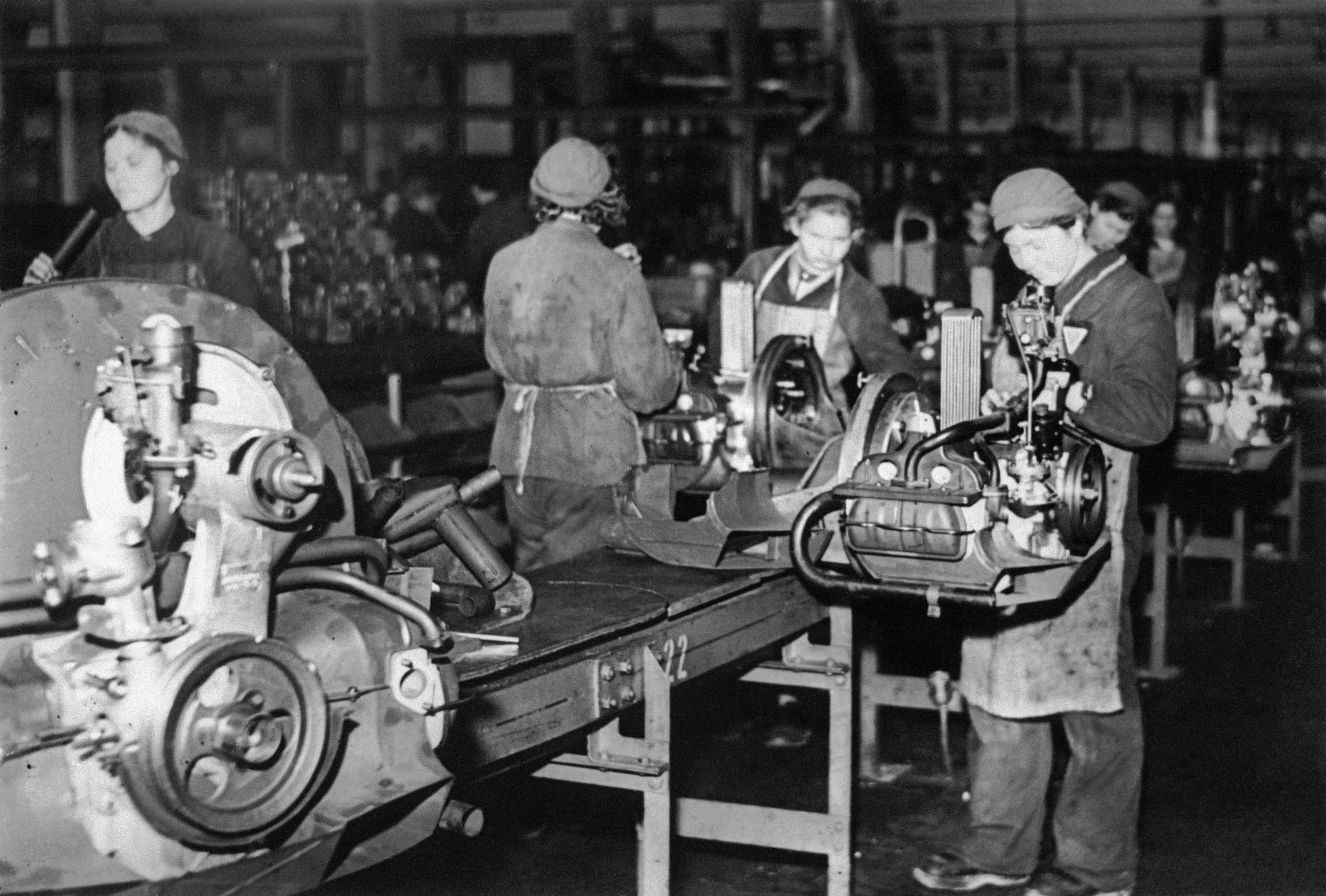

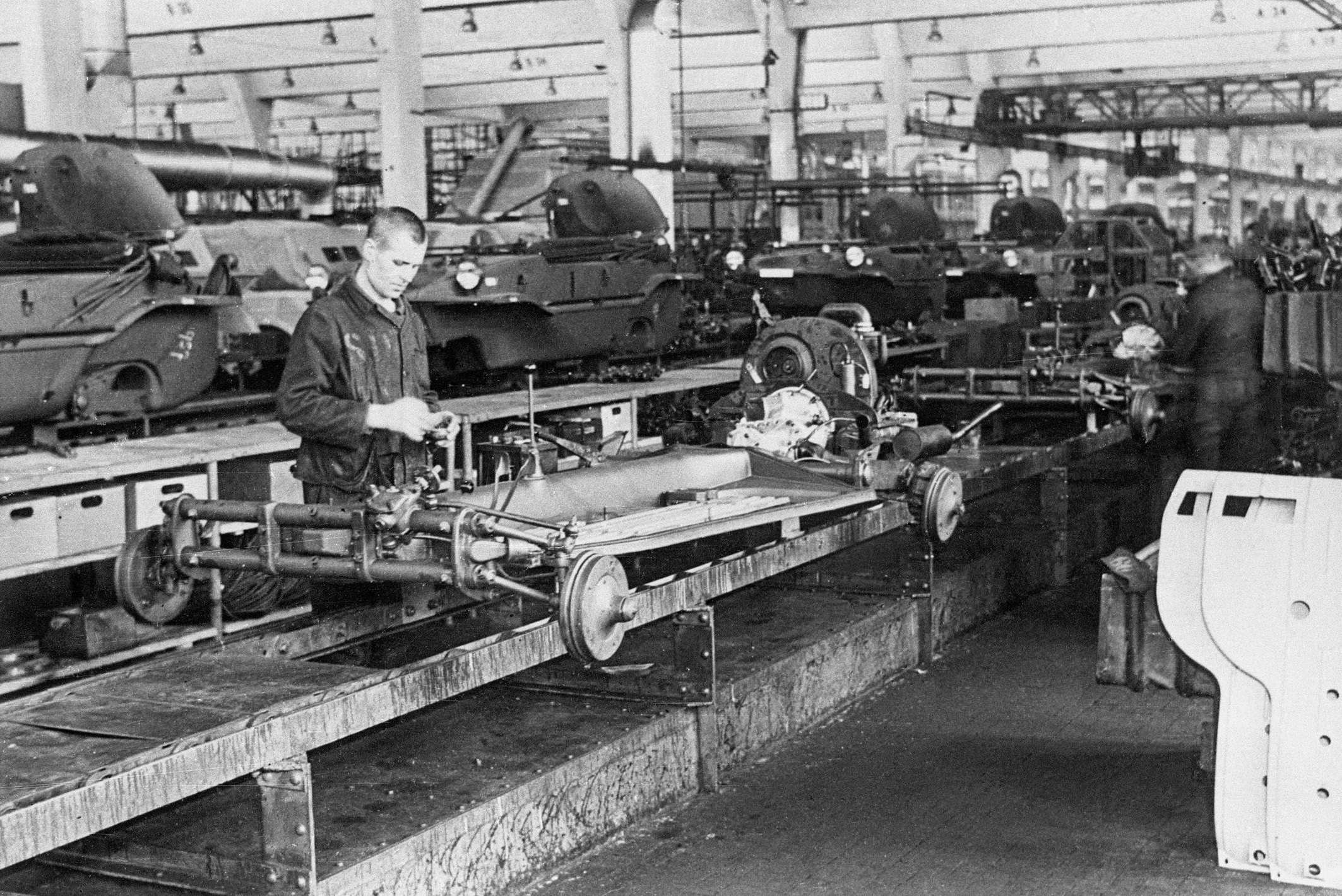

On April 10, the last 50 Kübelwagens (Type 82s) intended for the German army were completed at the Volkswagen plant as alarms announced the advance of the U.S. tanks into the area. The plant produced a total of 66,285 wartime vehicles.

The following day, U.S. troops liberated the plant and the city. Interestingly, the maps used by the U.S. Army did not even show the city or the plant.

Some of the freed laborers and prisoners of war unleashed their pent-up anger towards the Germans through plundering, destruction, and violence. To maintain order, the forced laborers formed a provisional security team consisting of French POWs and Dutch students who had been forced to work at the plant.

Fritz Kuntze, manager of the city’s power plant, took it one step further. Kuntze had refused to obey the orders given by the local Nazi leaders to blow up the power plant and surrounding bridges, and he—along with two other English-speaking engineers and Catholic priest Father Antonius Holling—drove to Fallersleben and convinced the American military that they should send troops to protect the plant. The U.S. Army agreed and sent additional troops on April 15.

Over the eight weeks that followed the plant’s liberation, American leaders made groundbreaking decisions for the democratic future of the freed laborers, the city, and the plant itself. The first democratic structures were established with the formation of a magistrat (municipal administration) and a stadtverordnetenversammlung (city council). At their first meeting on May 25, the council decided to rename the city Wolfsburg.

Also in May, the plant began producing Kübelwagens—known as “Volkswagen Jeeps”—for the U.S. Army. The Americans also used the plant as a repair shop for their military vehicles.

The region became part of the British occupation zone at the end of June 1945. A total of 133 post-war Kübelwagen utility cars were assembled.

Although conditions were still challenging, production of the civilian Volkswagen Type 1—forever known as the Beetle—began just after Christmas 1945.

In all, about 20,000 people had been forced for Germany to work for the former Volkswagenwerk GmbH. On the day of liberation, there were about 9100 people working at the plant, of whom more than 7700 were forced laborers.

Volkswagen provided the first-hand accounts below.

Henk ‘t Hoen (1922–2006), a Dutch student forced to work at the plant from May 1943–April 1945:

“When the first American troops arrived via the neighboring town of Fallersleben, we students immediately established contact with them. Together with some former French prisoners of war, the students had set up a provisional security group to calm down the escalating situation. This group had obtained weapons and vehicles at the plant and used the fire station as its headquarters. As the American troops advanced … directly from Fallersleben to the river Elbe, and at first [they] simply ignored the Stadt des KdF-Wagens; our group had to bridge the time until the occupation forces arrived.

“With some persuasion, we finally succeeded in having a few American tanks drive through the city. Our group preceded the tanks in a Kübelwagen in an attempt to enforce the curfew that had been imposed. Shortly afterwards, the military government established a city commander’s office and we were ordered to hand in all our weapons. The security group was then dissolved. Some of the students who had established the first contacts with the American troops disappeared shortly afterwards, heading back to the Netherlands at their own initiative. The official transports came later.”

Jean Baudet (born in 1922 and now living in Nice), a French forced laborer from July 1943–April 1945, experienced the liberation in Neindorf:

“Sunday, April 8 — The front is coming nearer. One rumor follows another. Smoke rising at Gifhorn. Presumably sabotage on the oil pumps. Battles in the air. Masses of trucks, cars and soldiers on bikes on the road. My Tyrolean backpack is ready. Only the clothes I need but tinned meat, milk, fat, sugar, a few biscuits. Whatever happens, I want to be ready to head home before, during or after the fighting.

“10 April — Sunny weather. Artillery fire the whole day. All the Germans are drunk. Columns of soldiers without weapons and wounded pass by. Complete chaos. When will it all be over?

“10 April — Evening: artillery fire nearby. Impressive. Bombs fall on Brunswick throughout the night. Troops are always moving past.

“11 April — 9 a.m.: American bombers over the treetops. People say that KdF has been occupied. They’ve already advanced up to Barnstorf. That’s behind the forest. We pack our things, singing as we do so. Machine-gun fire can be heard. They must be here any time now. The grenades are coming closer and closer.

“11 April — Afternoon: Complete silence. Sunny weather. Peace has returned. Only a few severe explosions from time to time. The highway bridges are being blown up. At 2 p.m., farmers give us bacon soup and a piece of bread. We don’t understand what has come over them. At 3 p.m., there is a major alarm. We have to evacuate. So ‘off to battle.’ I decide to hide in the bushes with Georges Chauvineau but we are worried about gunfire in the forest. 3:30 p.m. contradictory order. Everybody is happy: we stay where we are. We immediately get out our cigarettes and football. The evening and night are peaceful.

“12 April — The sky is overcast. All quiet. Is the war over? Where are they? What are they doing? 12 noon. 5-minute alarm, fighting on all sides again. We are surrounded. Artillery, bombs, anti-tank grenades, machine guns, all at once. They are coming!

“12 April — 2 p.m. The farmers come back, bringing us sacks of potatoes. I’ve seen everything now! 3 p.m. They’re here. They’re here!”