50 Years Ago, Evel Knievel Tried to Jump the Snake River Canyon

The week marks the 50th anniversary of “King of the Stuntmen” Evel Knievel’s not quite successful attempt to jump Idaho’s Snake River Canyon in his steam-powered rocket X2 Skycycle. From humble beginnings in a rough Montana mining town, Knievel took a talent for bluster and bravado and an unhealthy attraction to risk and made himself into an American icon, breaking more than a few bones in the process. (You can read more about Knievel’s life and his many stunts in Cameron Neveu’s profile of him here—Ed.) While he successfully completed several jumps and established records, in many ways it was his spectacular failures and his crash landings, that brought him the most attention, including his most famous attempt at Snake River.

Robert Craig Knievel was born in 1938. As a copper miner in Butte, he gained a reputation as a man willing to make a bet, take a dare, and back up his opinion with his fists. While thrill shows using cars and motorcycles had been around since the early automotive era Knievel got the idea of turning jumping cars on motorcycles into a quasi sport. Initially gaining regional attention in the western United States, he came to national and international fame when Wide World of Sports, a popular omnibus sports show that aired every Saturday afternoon on the ABC television network, broadcast film of his attempt to jump the fountains at the Ceasars Palace casino in Las Vegas on New Year’s Eve 1967. The brutal, graphic images of Knievel’s failure to stick the landing at Ceasars caught the attention of the TV show’s producers and the general public. This pseudo-bloodlust ensured that Knievel’s jump attempts would become a staple for WWOS and his appearances on the show earned standing as seven of the series’ ten most popular episodes, including its highest rated show.

With each successive attempt, Knievel tried to outdo himself, attempting ever more outrageous jumps, like jumping over thirteen London buses in Wembley Stadium, or over a tank of live sharks (itself inspiring the “jumping the shark” episode of the Happy Days sitcom). Knievel wasn’t just a daredevil. He had an instinctive gift for self-promotion, modeling his public persona after entertainers like Elvis Presley and Liberace, and wearing custom leather jumpsuits for his jump attempts. His color scheme was typically a patriotic red, white, and blue.

Today, motorcycle and car stunts are planned by teams of engineers using computers, with every detail modeled and simulated down to the millisecond. Evel Knievel was certainly no engineer. He did it mostly by the seat of his leather pants. For example, because of an endorsement deal many of his most famous jumps were attempted using Harley Davidson motorcycles, though they were hardly the most suitable machines for the job. There’s a big difference between getting big air on a lightweight motocross bike with plenty of suspension travel and attempting the same stunt on something much heavier, with a suspension designed for cruising down the highway.

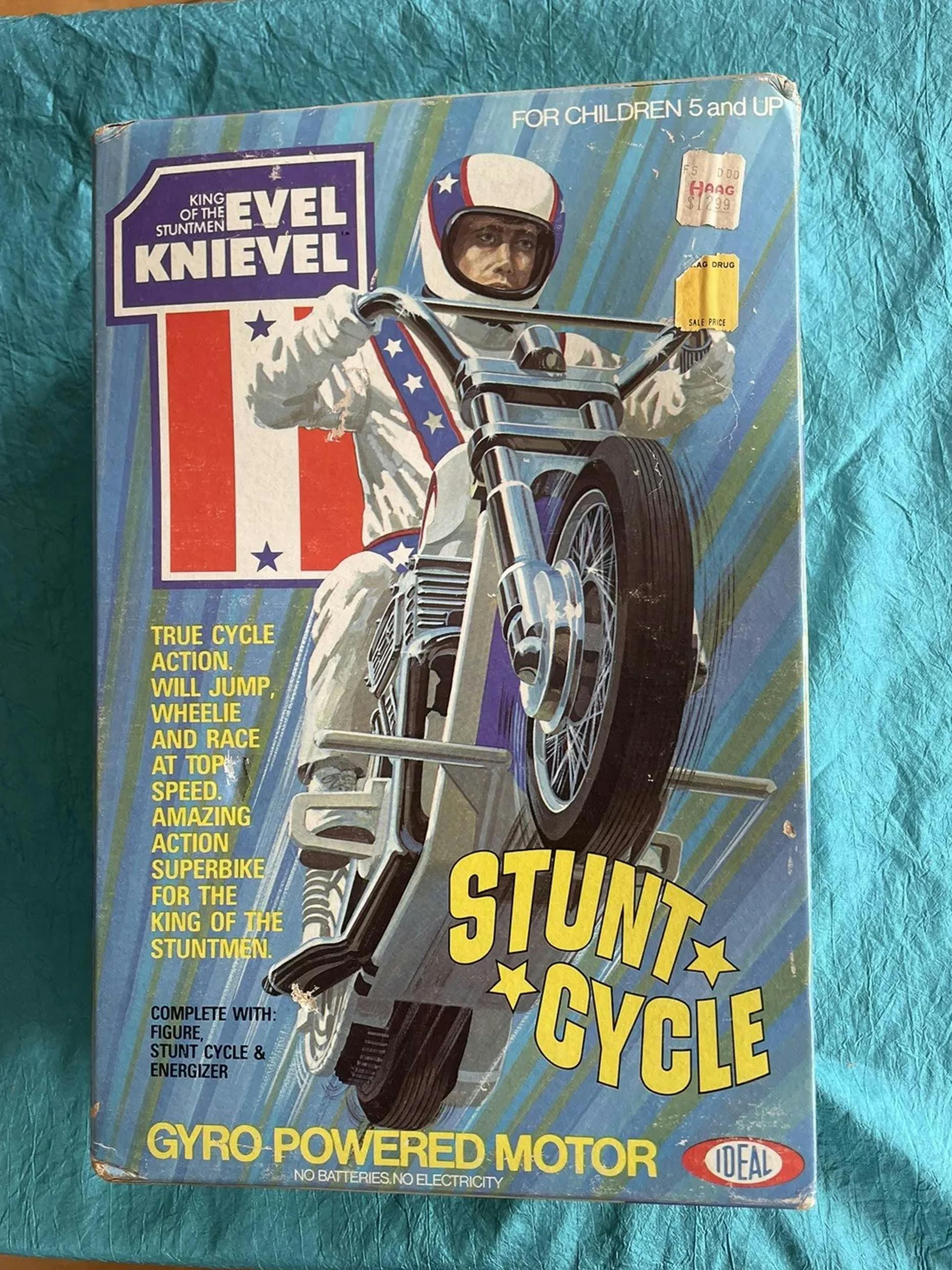

Notwithstanding his spectacular failures, or possibly even because of them, Knievel became a phenomenon. A Hollywood biopic starring heartthrob actor George Hamilton followed, as did endorsement deals and sponsorships by companies like Mack Trucks and Chuckles candy. Bally marketed an Evel Knievel pinball game, said to be the last completely analog pinball machine made before the industry went digital. A licensing and endorsement deal with the Ideal Toy Company started in 1972 with the release of Evel Knievel action figures. The following year the Evel Knievel Stunt Cycle toy set was released. “Gyro-powered” with a flywheel, the Stunt Cycle came with a cranked “Energizer” launcher that allowed boys to try to replicate Knievel’s jumps, wheelies, and stunts in small scale, without the danger of trying those on their own bicycles.

Supported with lots of tv commercials (including scenes of Evel crashing), the Stunt Cycle was a huge success.

Girls were not ignored either, as Ideal also created an action figure based on a fictional female counterpart to Knievel, Derry Darling. The lineup of Evel Knievel toys from Ideal eventually included replicas of the Canyon Sky Cycle, an Evel Knievel van, Evel Knievel’s “Formula 1 Dragster” that he used for personal appearances and demonstration runs at dragstrips, and a variety of stunt kits. There was even, appropriately for Knievel’s overall brand, a toy ambulance. Ideal’s line of Evel Knievel toys was the company’s most successful to that date, selling an estimated $125 million worth of toys and accessories.

The toys were so successful that Knievel had a jet-powered trike, the Evel Knievel Jet Cycle, made in part to demonstrate at dragstrip exhibition runs, but mostly to augment the toy line.

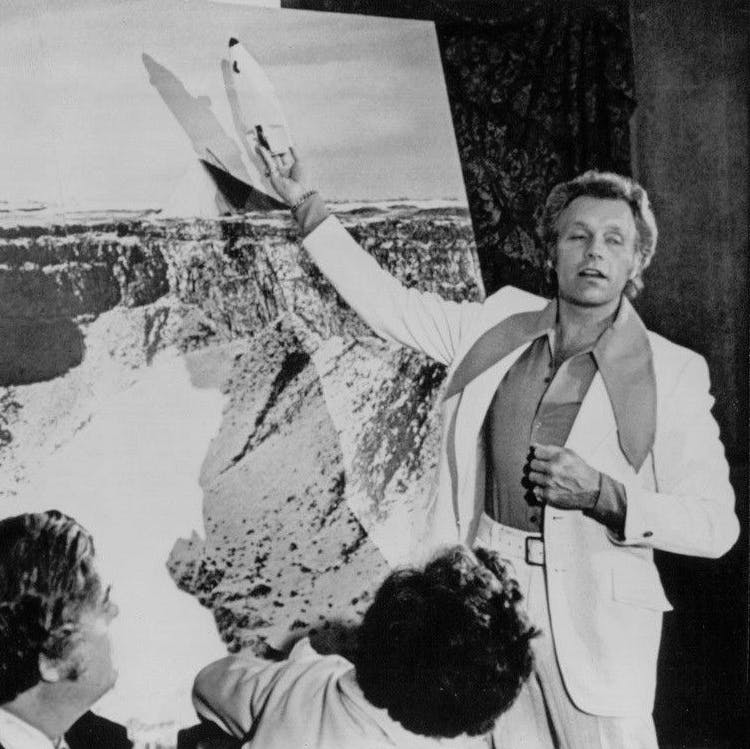

Following the Ceasars Palace attempt, Knievel started rumors that he was going to attempt a jump over the Grand Canyon in Arizona. He went public with his plan in 1968, stating, “I don’t care if they say, ‘Look, kid, you’re going to drive that thing off the edge of the Canyon and die,’ I’m going to do it. I want to be the first. If they’d let me go to the moon, I’d crawl all the way to Cape Kennedy just to do it. I’d like to go to the moon, but I don’t want to be the second man to go there.”

Over the next few years, Knievel would announce a series of concept bikes that he said would be used to jump the Grand Canyon and negotiated with the United States government to secure a site for the attempt. After the U.S. Department of the Interior officially denied him the use of airspace over the landmark in Arizona he started leasing land adjacent to the Snake River Canyon in southern Idaho, which was not under federal jurisdiction, in 1971.

Once the site was selected, Knievel brought in Robert Truax, who had worked for the U.S. Navy engineering rockets and missiles, to design the X2, which was really more of a rocket than a motorcycle. It had wheels but those were meant to roll on the Skycycle’s launch ramp, not on the ground. A relatively simple Newtonian machine, the X2 used high pressure steam for propulsion.

Originally, Knievel intended to use an ejection seat to parachute safely to the ground after the Skycycle traversed the gap, but that proved to be too expensive to implement. Instead, the entire vehicle was given a parachute, which would theoretically lower it safely, nose down, with Knievel still on board. A shock absorber in the nose cone was supposed to cushion the landing forces. Remember, this was a half century before Space X was able to reliably land rocket stages on earth.

Three X2 Skycycles were made, using surplus military jet fuel tanks as fuselages and go-kart seats for the cockpits. That the first two Skycycles failed in their test flights over the Snake River is evidence of just how brave, or foolish, Knievel was.

On September 8, 1974, about 15,000 spectators paid $25 each to watch the jump in person. With prominent boxing promoter Bob Arum managing the event, many thousands more watched the event for $10 on pay-per-view closed circuit television at hundreds of movie theaters across America. To give you an idea of how big the event, which was later broadcast on Wide World of Sports, was, famed journalist and TV host David Frost anchored the closed-circuit telecast, accompanied by ABC News science editor Jules Bergman and Apollo 13 astronaut James Lovell.

Knievel almost succeeded and he did actually manage to jump over the canyon. The X2 Skycycle appeared to launch perfectly and ABC’s aerial cameras did show that the trajectory reached over the other side of the canyon. The vehicle’s parachute, however, opened up prematurely while the X2 was still ascending on the launch ramp, slowing the rocket and eventually causing it to drift back over the canyon instead of landing on the other side. The Skycycle hit the far canyon wall, crumpling the nose, and it fell to the riverbed. Fortunately, it didn’t end up in the river, which could have resulted in Knievel drowning since he needed help to unstrap his safety belts.

There were rumors that Knievel got cold feet during the launch and triggered the parachute early. He and Truax blamed each other but analysis determined that it was a design flaw. The way the chute retention cover was designed did not take into account aerodynamic drag, which pulled the cover open and the chute out. In time, Bob Truax said the failure was his own fault.

Robert “Evel” Knievel died in 2007. While Knievel was alive his son Robbie carried on the family tradition, successfully completing many jumps. Robbie is now retired from those exhibitions and the Knievel family operates a touring exhibit of Evel and Robbie’s cars and bikes and related Evel Knievel memorabilia, including the X2 Skycycle, the Evel Knievel Dragster, an extensive collection of those Ideal toys, and a well-stocked merchandise trailer. You can even buy reproductions of the Evel Knievel Stunt Cycle if you want to relive your childhood.

Evil was quite the showman. He showed more guts making these jumps than anymore I have seen. His bikes were never anything you would use to jump.

The rocket deal he expected to die and was scared. He went into the river hoping he could get out but though he may drown. He never expected to make the other side.

I had the toys and still wish I had them today,.

But there was an ugly element to Evil. He really destroyed his family. His Ego got the best of him and hurt all those around him. His wife yet can not own property as she is part of the law suits that he failed to pay.

He did find faith as he aged and he did try to patch things up but it was tough.

What really hurt was to see Robbie drink himself to death.

The Evil story is an amazing one but the dark side makes for a sad ending.

Evil lived here in Ohio for a while. He was painting and trying to raise money with his art. His final years were far from his height of fame.

A lot can be learned from him on what to do and what not to do in being a showman.

“that allowed boys to try to replicate Knievel’s jumps, wheelies, and stunts in small scale, without the danger of trying those on their own bicycles.”

Trust me, it didn’t work. Most of us still tried to replicate the jumps on bicycles or dirt bikes if we had one. And we met with even less success than Knievel, with maybe a few less broken bones.

No we still did the bike jumps. Much of this led to BMX bikes we have today.

Just thought about this the other day as we drove by the Snake River this last week.

Evel and the Skycycle made Twin Falls, Idaho almost as popular as that little music festival called Woodstock out in New York in ’69 – at least with the biker crowds!