Where the NSX succeeded, these 3 mid-engine Japanese moonshots failed

The original Honda (and for Americans, Acura) NSX was a triumph of design, engineering, and performance. The aluminum-intensive monocoque, expert tuning, and precise build quality came together in a package that not only challenged the Italian exotic competition, but proved light-years more reliable and livable than those established players. When it debuted in 1990, the mid-engine marvel dazzled the automotive world and helped cement Honda as a force to be reckoned with on the global stage. Moreover, the NSX gave Acura a critical weapon to help separate itself from Infiniti and Lexus, both newly minted premium marques arriving from the Pacific at that time.

Looking back thirty years later, it’s no surprise that a mid-engine sports car as sophisticated and groundbreaking as the NSX exploded out of Japan amid the peak of the country’s economic bubble. The real question is, why was it the only Japanese supercar of that moment? Remember: Lexus and Infiniti fully put their eggs in the luxury sedan basket with the LS and Q45, while the Toyota MR2’s target was firmly mid-market. Of all the marquee sports cars Japan’s leading lights produced in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Mitsubishi 3000GT, R32 Skyline, and Mazda RX-7 included) it might seem as if Honda was only automaker from the island that dared challenge Ferrari and Lamborghini head-on.

In fact, Honda did indeed inspire a few rivals chasing the same apex. Ambitious as these mid-engine performance machines were, would-be NSX-fighters from Nissan, Yamaha, and Isuzu simply couldn’t clear the obstacles—economic, engineer, and otherwise—that Honda victoriously hurdled so gracefully on its way to becoming an icon.

Nissan MID4

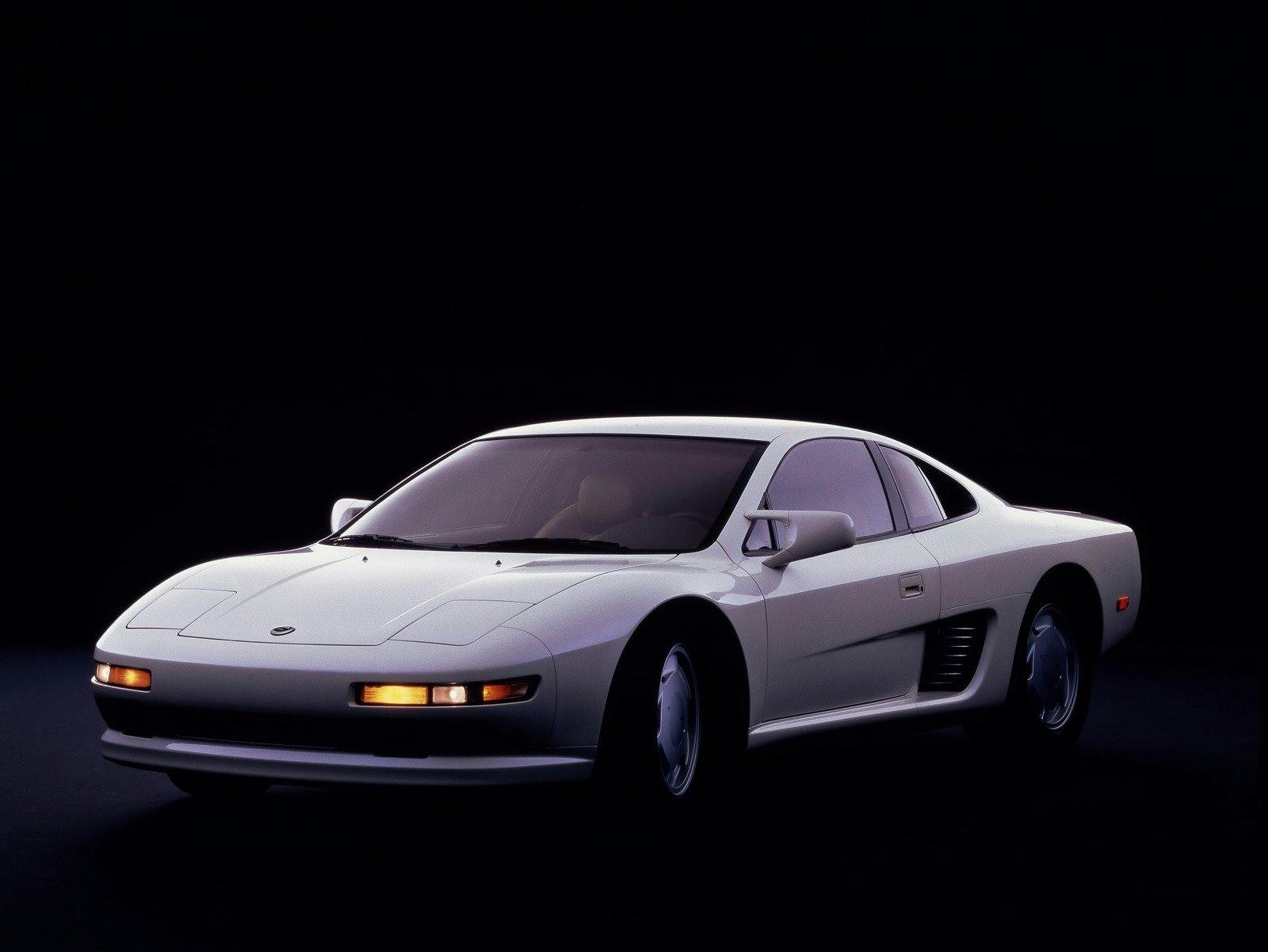

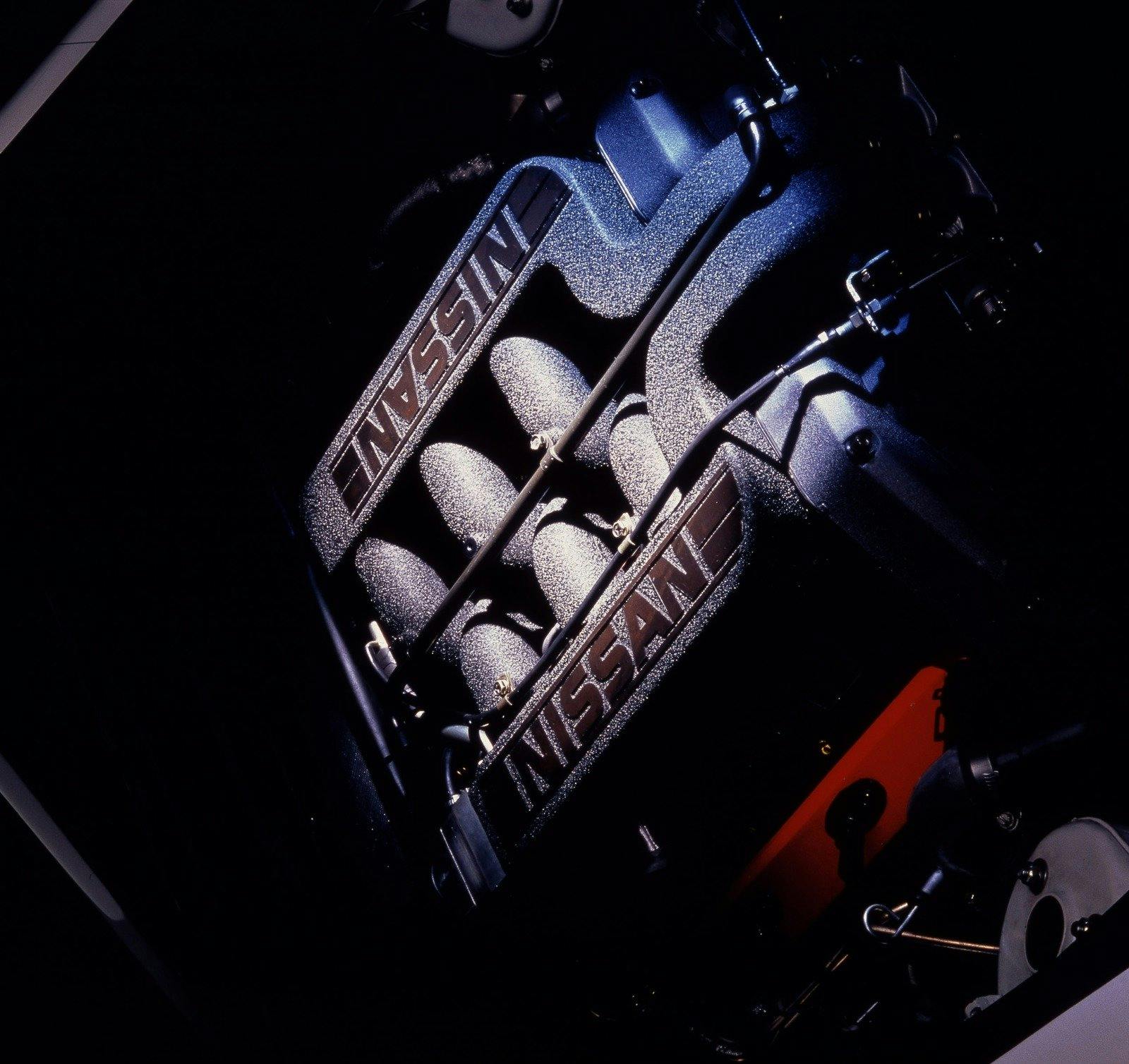

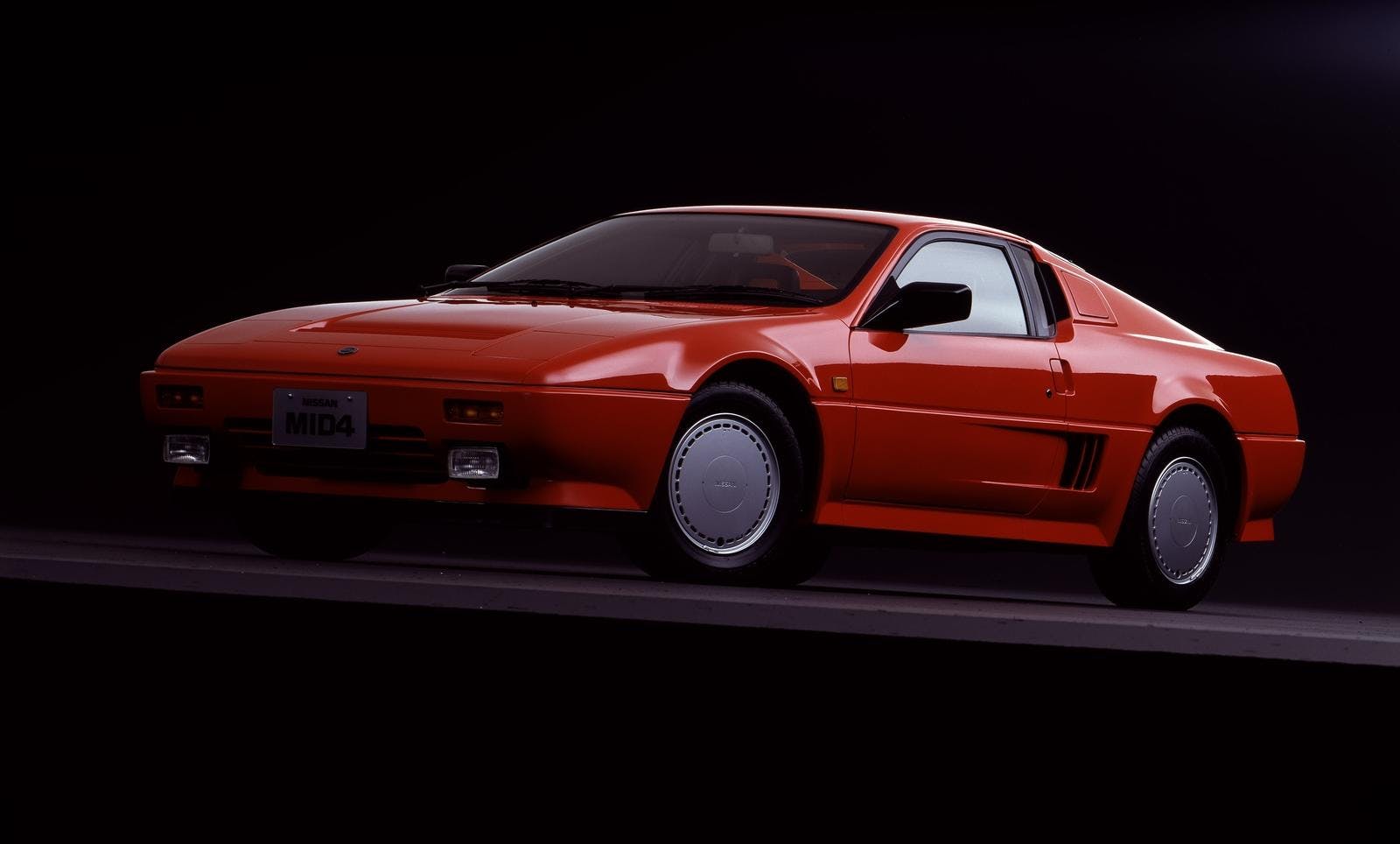

Nissan got into the mid-engine supercar game right around the same time as Honda, with both the NSX and the MID4 kicking off development in 1984. Nissan was much quicker out of the gate, introducing its prototype at the Frankfurt show in 1985, and the concept packed many of the technologies that would trickle down to other Nissans over the course of the next few years. Among them were the Advanced Total Traction Engineering System for All-Terrain (ATTESA) transverse-layout all-wheel drive system (later adapted to include “Electronic Torque Split” for longitudinal use with the Skyline sedans and coupes), and the four-wheel High Capacity Actively Controlled Steering (HICAS) system popularized by both the Skyline and the S13 and S15 coupes.

The original version of the MID4 was clearly intended to showcase the brand’s engineering know-how rather than challenge Europe’s supercar elite; despite its Esprit-baiting looks the coupe was wasn’t worrying anyone in Maranello with a 190-horsepower V-6.

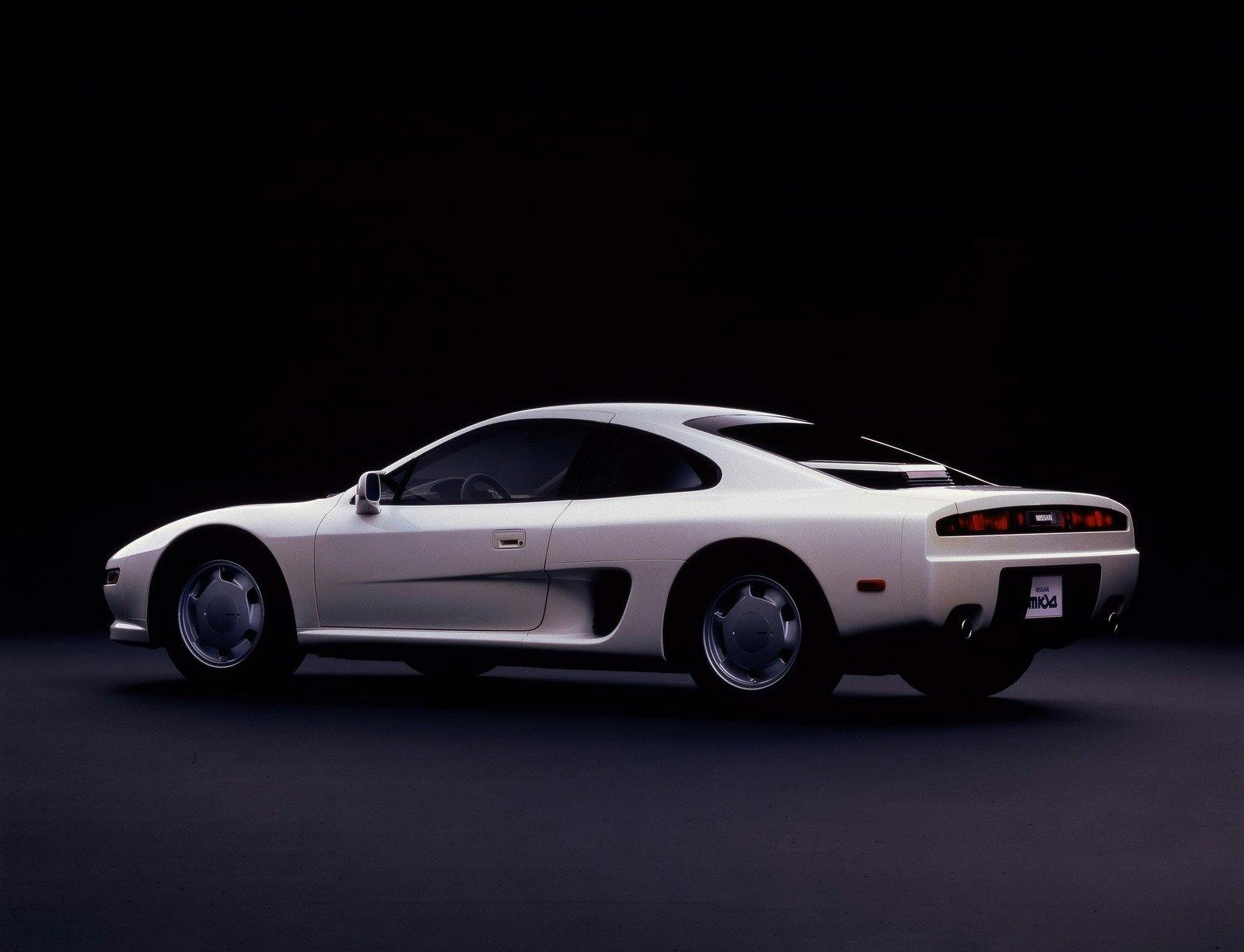

Nissan wasn’t done with the MID4’s evolution, though. A couple of years later the creatively-named MID4-II concept car would arrive, featuring a twin-turbo version of that same motor that offered up 325 horses.

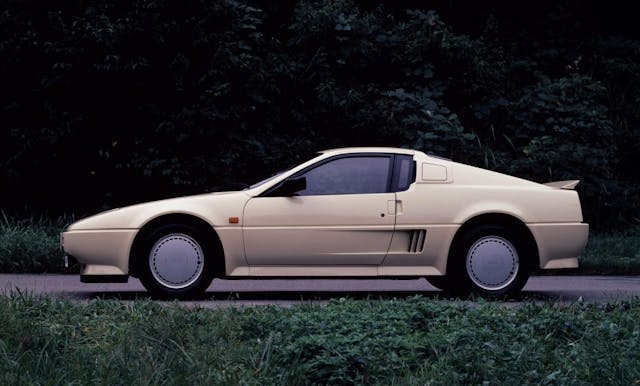

Nissan smoothed out much of the original effort’s styling for the MID4-II, giving it a swept appearance that resembles the brand’s next-generation flagship sports car, the Z32, which had yet to be introduced. The car featured numerous design cues that would more fully form in the 1990s, drawing comparisons to contemporary mid-engine Ferraris like the 308 and the 348.

Nissan would later prove it could deliver nearly every single one of its features into production—save its mid-engine platform—so what ultimately kept the MID4-II from dealer showrooms? Two primary concerns: The first was the cost of production versus the potential to recoup investment, given that so much advanced equipment was packed into what would no doubt prove to be a low-volume vehicle riding on a bespoke platform. Then there was the question of performance. With the Skyline GT-R selling well and the redesigned Z32 nearly ready for prime time (itself offering perhaps better dynamics than the MID4-II) Nissan balked at the notion of three high-end sports cars splitting potential profits.

Yamaha OX99-11

The success of the NSX inspired more than a few automakers to reach above their station, and the early ’90s quickly delivered a strong crop of one-off or ultra-low production supercars that mimicked its formula. Surprisingly, one of the companies to throw its hat into the mid-engine ring was Yamaha, which had almost zero experience producing road cars.

What Yamaha could count on was its incredible engine acumen. The brand had a proven track record of regularly partnering with bigger brands to tune or design performance powerplants. After producing a flurry of Formula 1 drivetrains that experienced varying degrees of success on the starting grid, Yamaha opted to recoup some of its costs by farming out the design of a sports car that could be built around one of its high-strung race motors.

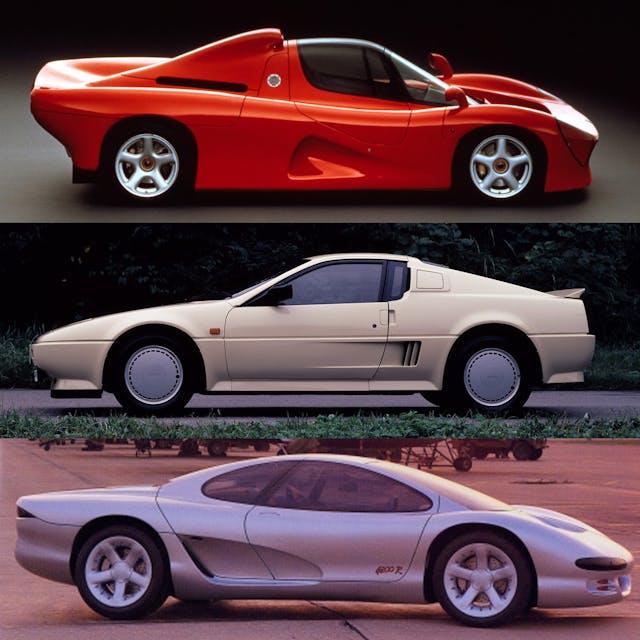

The design brief was simple: find a way to package the company’s 3.5-liter F1 V-12 (the OX99) and cut weight by using as much carbon fiber as possible in the process. A pair of concepts were proffered by both German and British companies, and the latter (International Automotive Design) emerged as the more striking of the two. The shape of the vehicle was outrageous, featuring a wild aero-bar across the front end that connected the vehicle’s fenders together and a single-seat center cockpit (later adapted to a tandem seat setup) that was like nothing else on the road.

It was a fittingly dramatic move for Yamaha, which wanted to shock the world in every way possible with its very first supercar. Unfortunately, IAD began to bicker with the Japanese brain trust concerning just how much it would cost to produce such a wild design using the available motor and materials. Frustrated, Yamaha pulled the project away and threw it in the laps of Ypsilon Technology, a wholly-owned company also based in the U.K.

Swapping firms didn’t change anything about the financial realities associated with the OX99-11 project. Nor did it remotely change the realities of Japan’s flagging bubble economy that was about to burst. Yamaha built three prototypes in 1992, each featuring a 400-horsepower, 10,000-rpm-redline V-12, but nothing ever reached production. Facing down a rumored $800,000 per-unit minimum to simply break even and a $1M price tag, the final 1992 burst of the Japanese asset price bubble ensured Yamaha never met its 1994 on-sale date.

Isuzu 4200R

Right around the time Nissan was preparing the MID4-II, Isuzu began exploring an upmarket push. Although it was known primarily for exporting commercial vehicles and building everyone’s favorite SUV rebadge candidates, the company had hit on some success with the sporty Piazza/Impulse hatchback and its tuning partnership with Lotus.

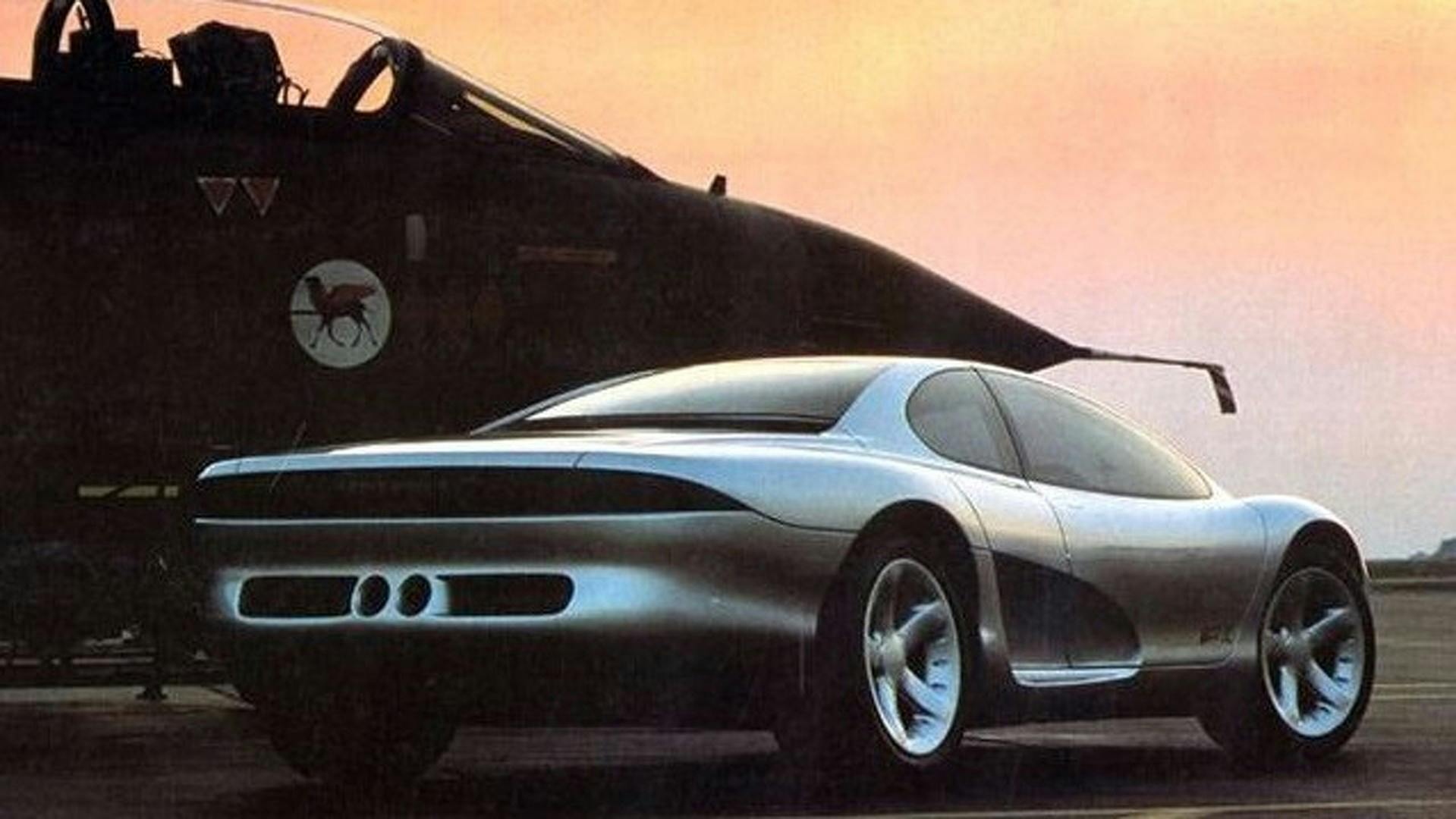

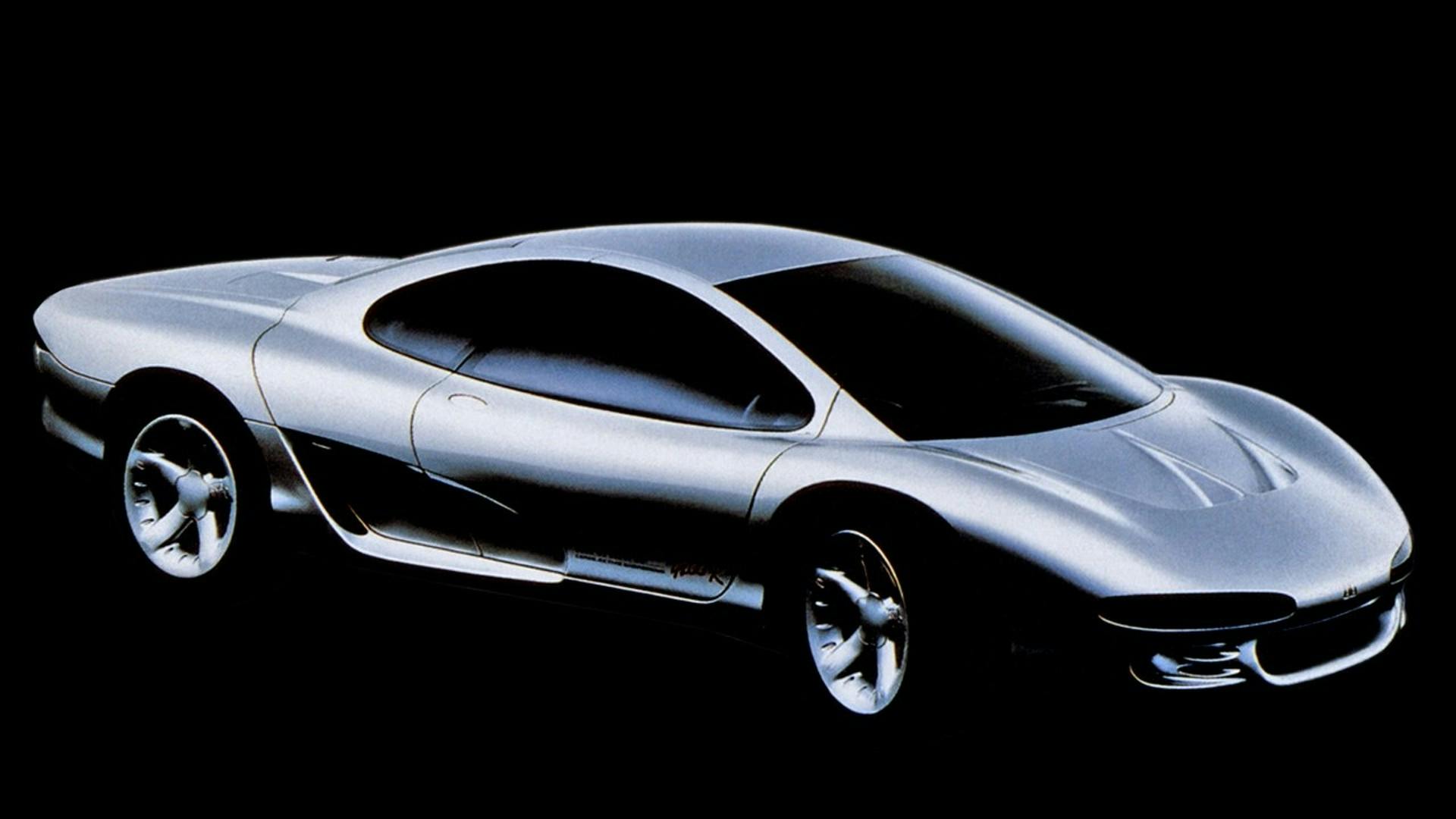

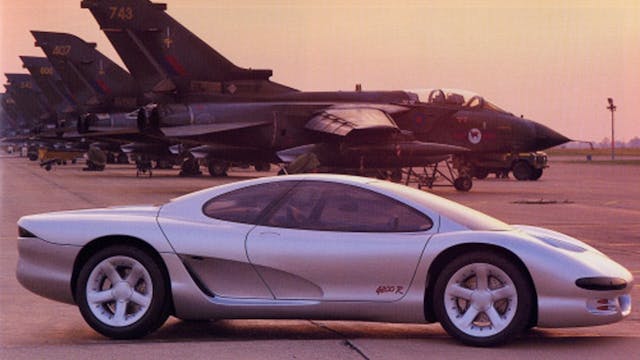

Given that corporate relations between the two companies were facilitated via their mutual corporate parent, General Motors, it only made sense for Isuzu to deepen the bond when it came to building its first GT supercar. To this end, Isuzu tapped a Lotus-based 4.2-liter V-8 engine (which featured dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder) as well as a suspension setup from the British brand, combining it in an unusual four-passenger coupe called the 4200R. Ultra-aero, ultra-cool.

Displayed at the 1989 Tokyo Motor Show, the vehicle looked as though it had been ripped straight from an arcade game. The 4200R’s elongated body (necessary for the larger cabin space Isuzu wanted) gave it unique proportions compared to most mid-engine coupes of its era. On top of that, it was stocked full of advanced gear like satellite navigation and a then-state-of-the-art fax machine, indicating that Isuzu was courting the luxury set rather than the pure sports car crowd. (Gordon Murray might have included three seats in the McLaren F1, but a fax was very much not in the brief.)

Of all the vehicles on this list, the 4200R was the only one to fall victim to the vagaries of corporate strategy. In 1992, Isuzu elected to stop building passenger cars entirely, shifting its attention to fully trucks and SUVs, and in doing so obliterating any hope of the super-GT finding its way to market even as a limited-production halo model. Decades later, 4200R designer Shiro Nakamura (who would go on to pen the Nissan 350Z as well as the Juke) would work together with Kazunori Yamauchi to create a digital version of the Isuzu that never was for the Gran Turismo video game series.