3 Automotive Urban Legends, Hoaxes, and Conspiracy Theories

Automobiles have been around for more than 120 years. It shouldn’t be surprising that, over that time, myths and lore have accumulated. Some of those stories are indeed true, like that of Henry Ford physically attacking the prototype of the restyled Model T that his son Edsel had commissioned on the sly. Others are fanciful and have that certain ring of urban legend, and there are even those stories alleged to involve dark secrets and conspiracies. Even paranoids can have actual enemies, of course, but most conspiracy theories deserve their association with headgear made of thin sheets of refined bauxite. However, as the rabbis of the Talmud taught, no lie can stand without a grain of truth to make it believable.

So without further delay, let’s look at three popular stories that are often repeated in various iterations as the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, that people swear happened to a friend of a friend of a friend. Enjoy the read, and then in the comments below, please tell us your favorite automotive urban legend, myth, or conspiracy theory.

Myth #1: Henry Ford’s Specifications for Parts Crates Allowed Him to Recycle the Wood as Floorboards

Our first tall tale has to do with Henry Ford, the subject of many such yarns. Allegedly, Ford Motor Company specified the size of crates used by component suppliers so the boxes could be carefully broken down and the wood panels repurposed as floorboards for Model Ts.

My favorite, rather elaborate, version of this story (elucidated here at the Jalopy Journal) hinges on what kind of plywood Ford used for floorboards. Of course, one commenter says, “the facts are true.”

Apparently, one of his outsource CEO’s got a call from Henry, not in regard to the product being sent to Ford, but the containers they were being shipped in. Ford started growling at the guy that the boxes were unacceptable and needed to be changed IMMEDIATELY! Ford then gave the fellow instruction on what type of wood to use, new dimensions, AND where to drill the holes and what type screws to use.

Now, as soon as the gentleman was off the phone with Henry, he was back on with of Ford’s execs, along the lines of, “the guy has finally cracked, etc”.

Well, the day came for the first shipment to arrive. Ford came down to the loading dock, with a train of exec’s waiting to see whether or not Ol’ Henry was ready for the happy farm… Ford asked one of his employees to move one of the boxes over to the assembly line, took off his jacket, unscrewed one of the boxes and put the board onto a chassis that was on the line.

I know that I embellished a bit (been a while since I’ve heard the story), and I don’t know what year it was, but the facts are true—Ford got free floorboards out of his supplier.

In reality, not much of that story is true, although Ford did use a lot of wood in making the Model T. It’s estimated that each Model T used about 100 board feet of lumber—for the floorboard, toeboard, dashboard, spokes for the “artillery” style wheels, and a wooden frame for the body’s steel panels.

Also, after the Dodge brothers (who were his primary supplier) parted with Ford, Ford Motor Company developed into one of the most vertically integrated manufacturing firms in history. Eventually, FoMoCo made its own steel from ore mined from its own mines, its own glass, and Henry even tried growing his own rubber trees in the Amazon. There was a period when Ford didn’t have that many outside suppliers. Because of his need for wood Ford owned about a half-million acres of forest in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, along with three lumber mills as well as a large industrial facility in Iron Mountain for milling that wood into usable parts. If anyone was making wood crates for Ford parts, it was Ford. Those wood crates, however, were not recycled into floorboards. There was a special department at the Rouge facility for recycling that wood into other crates.

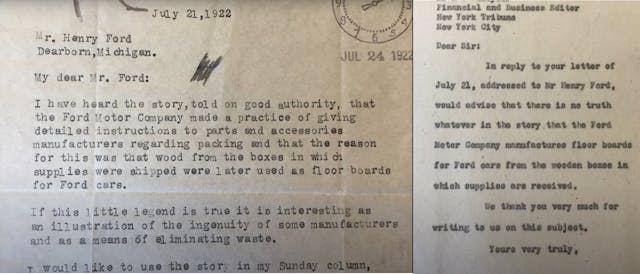

The urban legend dates back over a century. In fact, in 1922, the financial and business editor of the New York Tribune wrote Henry Ford to verify the story and Edsel Ford’s office replied, saying there was “no truth whatever” in the story.

One part of the story that is true: Henry Ford was very much into recycling. The Iron Mountain facility didn’t just make wood parts (and bodies for “woodie” station wagons and eventually military gliders during WWII as well). It processed sawdust, wood scraps, and other waste materials into usable materials like methanol, creosote, and charcoal briquettes.

Myth #2: GM Bought Up Streetcar Companies to Kill Public Transportation and Sell More Cars

The idea of big corporations conspiring to increase profits at the public’s expense is an easy one to sell to credulous people, even some who are initially skeptical.

This particular conspiracy theory has been amplified by Hollywood, via the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and on public television through the documentary Taken for a Ride. Here’s how it goes: In the mid-20th century, American cities had inexpensive, efficient, and convenient public transportation provided by streetcars running on rails and powered by overhead cables. General Motors changed all that when it bought up streetcar companies and purposefully stymied them by increasing fares and decreasing service. All of this was supposedly a step in ultimately replacing them with buses that were more profitable to GM, but less convenient to riders. In turn, the add-on effect would be to persuade now-unhappy public transportation riders to switch to privately owned automobiles.

We actually know the origin of this conspiracy theory. Fifty years ago, a newly hired attorney named Bradford Snell, working for the U.S. Senate on antitrust matters, testified that the government had criminally charged “…General Motors and allied highway interests for their involvement in the destruction of 100 electric rail…systems… throughout the country.”

Snell further said that a “federal jury convicted GM of having criminally conspired with…others to replace electric transportation with gas or diesel-powered buses,” and that the streetcar systems had been “vastly superior” in terms of speed and comfort to the internal-combustion-engine-powered buses that took their place.

Snell concluded,

“The noisy, foul-smelling buses turned earlier patrons of the high-speed rail systems away from public transit, and, in effect, sold millions of private automobiles…General Motors’ destruction of electric transit systems across the country left millions of urban residents without an attractive alternative to automotive travel.”

Let’s break this down. It’s indeed a historical fact that the General Motors-affiliated companies (with investments from Firestone, Standard Oil and other companies in the oil and transportation sectors) National City Lines and Pacific City Lines started to purchase municipal trolley systems starting in the late 1930s. It’s also a fact that, in a few short years, those streetcar lines went out of business, to be replaced by municipal bus lines. As well, it’s a historical fact that GM, Pacific City, and other firms were indicted in 1947 for conspiring to monopolize the interstate sale of buses, fuel, tires, and other supplies to their captured transportation companies, as well as conspiring to form a transportation monopoly. While most of those companies were convicted on charges of monopolizing the sale of buses and related materials, they were acquitted of the charge of trying to monopolize transportation in general.

Transportation Quarterly is an academic journal published by the non-partisan Eno Transportation Foundation. In 1997 it published a paper by Cliff Slater titled General Motors and the Demise of Streetcars arguing that there was no conspiracy. Slater argued that the trolley systems were replaced by buses for strictly economic reasons. Buses were cheaper to run than streetcars and were much less expensive to implement because they didn’t need railways. Cities and suburbs were expanding rapidly, and it was much easier, cheaper, and faster to simply add another bus stop on existing roads, rather than extend the rails.

The paper further asserts that it wasn’t the death of streetcars that increased private car ownership; it was the other way around. Before the popularization of the private automobile, if you wanted to get to work on time, you took pains to live within a 30-minute walk of a streetcar line. The convenience of driving directly to one’s destination in privacy and comfort won out over taking a crowded trolley and then having to walk blocks from the trolley stop to one’s final destination. Additionally, having a private automobile makes shopping and carrying home your purchases more convenient.

In 2010, CBS’s Mark Henricks reported:

There is no question that a GM-controlled entity called National City Lines did buy a number of municipal trolley car systems. And it’s beyond doubt that, before too many years went by, those street car operations were closed down. It’s also true that GM was convicted in a post-war trial of conspiring to monopolize the market for transportation equipment and supplies sold to local bus companies. What’s not true is that the explanation for these events is a nefarious plot to trade private corporate profits for viable public transportation.

Myth #3: The 200-Mile-Per-Gallon Carburetor

This myth also has to do with alleged suppression. In this case, oil and car companies supposedly kept a highly efficient carburetor off of the market.

In truth there are, ahem, manifold reasons why the auto industry moved away from carburetors and embraced electronic fuel injection. Controlling emissions was probably the, ahem, driving factor but the simple fact is that fuel injection works better. (Editor’s Note: Ronnie’s throat-clearing quota has been reached. One more and we pay him in lozenges.) What’s surprising is that despite the indisputable superiority of fuel injection, stories about miracle carburetors continue circulating to this day. What’s not surprising is that, despite the change in technology, there are still dubious fuel-saving devices on the marke. Many claim to work via your car’s OBD II port or even the 12V power socket.

As with other urban legends and conspiracy theories, this one has a compelling story. Variations abound.

Here’s the gist: Someone takes delivery of a car from a major automaker. In some versions it’s a retirement gift from the company, in others a couple arranges for a factory delivery. They are shocked to discover that the car achieves unheard-of fuel economy. In some tellings, it’s 100 mpg; in others, it’s as much as 200. Of course, nobody can ever prove it because these stories usually end in one of four conspiracy-laden ways:

- Mysterious men show up, pop the hood, make a few adjustments and the magical mileage returns to normal.

- The automaker recalls the car. It is either replaced by another car or the original car is returned, minus the unusually efficient gas mileage.

- Guys in suits with briefcases of cash show up and make an offer that can’t be refused.

- The car is stolen or otherwise disappears overnight.

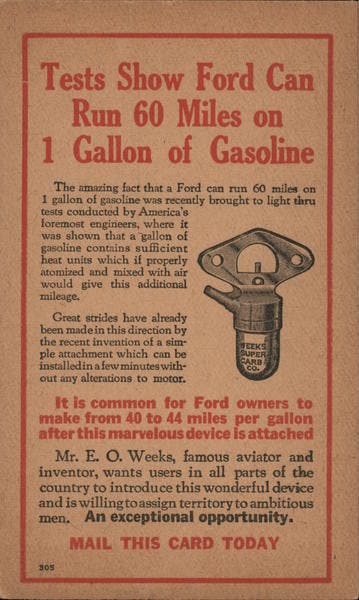

The popularity of this particular urban legend has arguably tilled fertile ground for scam artists promoting dubious inventions. You may have heard of scams such as the “Fish Carburetor.” To make matters more confusing, while there have been multiple cases of such fraudulent products, there was a genuine, non-scam Fish carburetor.

We’ll get to the real-deal Fish carb in a moment, but first, let’s look at the Pogue carburetor. The Pogue’s story contains many elements essential to nonsense narratives of this type, though I think the story might be best characterized as a hoax, rather than a scam, since no money or products ever changed hands.

Charles Nelson Pogue (1897-1985) was a mechanic and inventor from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. From 1927 to 1934, Pogue successfully filed for four carburetor patents, U.S. patent 1,750,354, U.S. patent 1,938,497, U.S. patent 1,997,497, and U.S. patent 2,026,798. While some reports describe Pogue’s carburetors as catalytic, none of the patents mention the use of catalysts. What the patents do mention is vaporization. Some context: One problem that affected early carburetors was an inability to fully aerosolize fuel, resulting in small drops of liquid fuel remaining unburned. If you could better vaporize the fuel, people deduced, you’d get more power and better fuel economy because of more complete combustion.

In 1936, the Canadian Automotive Trade magazine reported that a car equipped with the new carb was able to travel 1879 miles on just 14.5 gallons of gasoline. (That works out to 129.5 mpg.) A Winnipeg car dealership manager claimed to have achieved 217 mpg after fitting a Pogue carburetor to his car. Another dealer claimed to have gone 26 miles on just one pint, which is 208 mpg. As the stories spread through Canada, the reports and rumors proliferated.

To his credit, Pogue denied these reports. Some said that thieves had broken into Pogue’s shop and had stolen some of his carburetors to either discover its secrets and/or suppress its production. Wealthy Canadian backers were rumored to be negotiating with Pogue for the rights but the deals somehow never came to fruition. Some believed Ford of Canada had bought the rights to the technology.

P.M. Heldt, the engineering editor of Automotive Industries magazine during that period, in regard to a diagram of the Pogue carburetor, said, “The sketch fails to show any features hitherto unknown in carburetor practice, and absolutely gives no warrant for crediting the remarkable results claimed.”

Critics wanted to see the miracle carburetor, but Pogue apparently never demonstrated a working version, nor did his carburetor ever see series production. Of course, as these things go, the fact that the Pogue carb never saw the light of day is pointed to as further evidence of the conspiracy to suppress it. Thus, the story continues to be perpetuated. The fact that there is no record of Pogue ever assigning rights to his patents to anyone, including car and oil companies, doesn’t get as much air among conspiracy theorists.

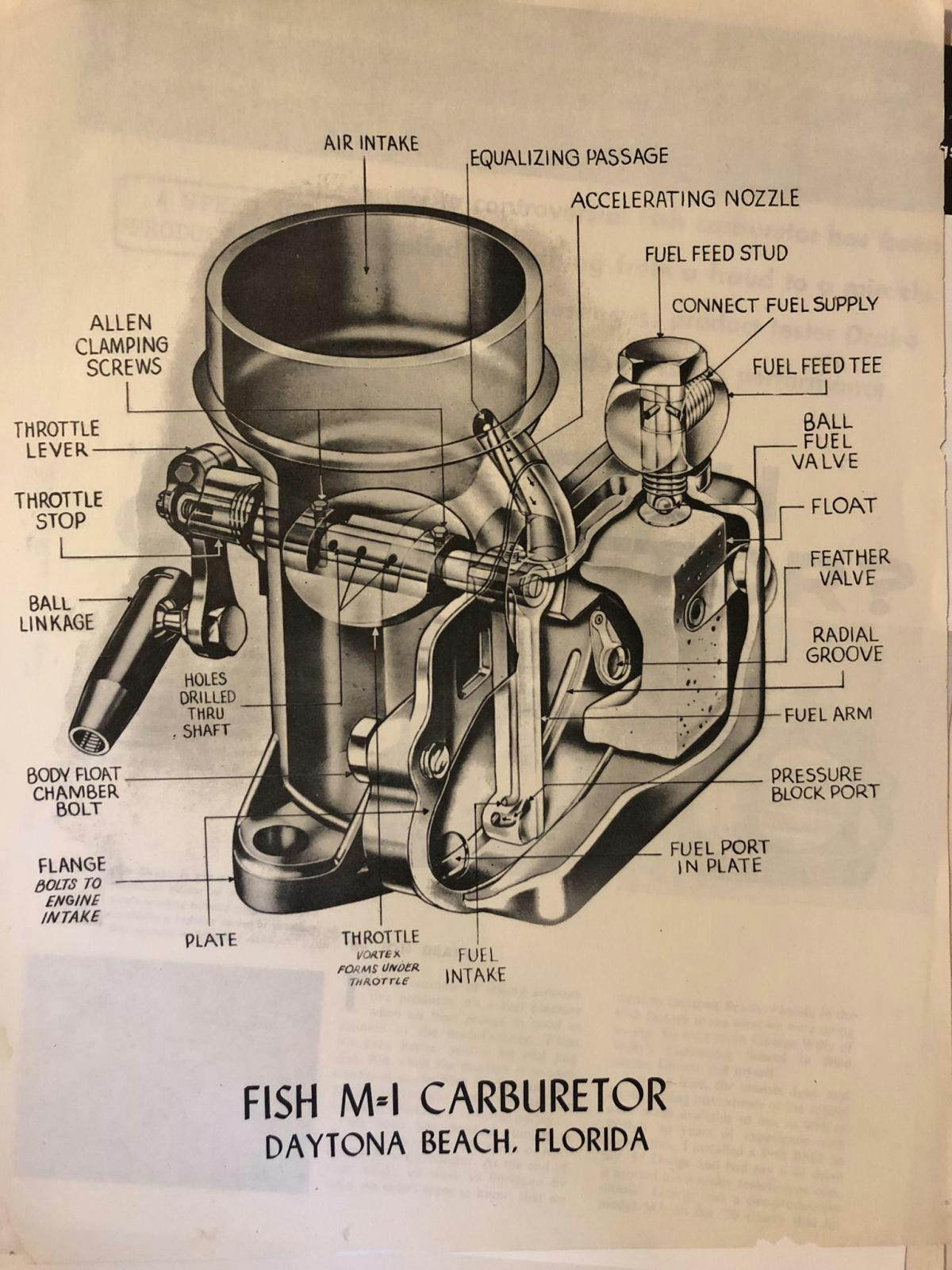

Unlike the Pogue carburetor, the Fish Carburetor Company actually produced working carburetors—over 125,000 of them from 1947 to 1959. Invented by hot rodder John Robert Fish in the early 1930s, and protected by three U.S. patents, the Fish design was meant to solve the problem of carburetors’ float chambers. Carburetors use a float chamber to meter fuel to the jets; the chamber fills with fuel and a float attached to a valve shuts off the fuel when the chamber is filled. Acceleration, cornering, and braking forces can affect the position of both the float and the fuel, interfering with fuel delivery and causing drivability issues.

The original intention of the Fish carburetor was to avoid the weaknesses of the float chamber and its sensitivity to the forces of acceleration and cornering. The sources I found give two different descriptions of how Fish’s invention worked: One source says that the carb operates on pressure differential—not air speed. The other says that it sensed the mass of the airflow rather than the volume. Either way, the Fish device was said to be self-adjusting and self-compensating to changes in weather or altitude. The Fish design also did away with accelerator pumps with a clever ram air design.

Instead of the single jet of conventional units, the Fish carb delivered fuel using six to ten jets built into the throttle spindle, which was said to produce better fuel atomization and vaporization, thus improving fuel economy, power, and cold-weather starting. Fish claimed 20 percent better fuel economy and 30 percent more horsepower when compared to conventional carburetors.

The Fish carb got a publicity boost when stock car legend Fireball Roberts swapped out the OEM four-barrel carb in his Hudson Hornet racer for a couple of Fish units, to some success. The Fish induction system became popular in the early days of stock car racing.

Now here’s where the Fish story gets a little bit, ahem, fishy. (Editor’s Note: So will it be Halls or Ricola?) Supposedly, original equipment carburetor makers conspired to put Fish out of business. Fireball Roberts was said to have done well in qualifying, but somehow his tires never lasted the way they did for factory-supported stock car teams. The United States Post Office allegedly started marking all of Fish’s shipments “FRAUDULENT,” returning them to sender with claims that the carburetors were not actually being produced. (That’s a little bit odd considering that there’s an archival photo of the production line in Daytona.)

It’s worth remembering that the era in which Bob Fish was operating was one during which time federal bureaucrats and prosecutors effectively put Preston Tucker out of business, though a jury acquitted him and his associates of any wrongdoing. It thus seems possible that overzealous postal inspectors, concerned about gas-saving gadget scams, targeted an innocent company.

The way the story goes, the Post Office’s actions resulted in the carburetor’s rights being reassigned to a Canadian company, which sold them outside of the United States.

The Fish carburetor truly did develop a following in the hot rod community, and the Brown Carburetor Company of Draper, Utah put it back into production, making about 10,000 new Fish-design carburetors from 1981 to 1996.

On the Jalopy Journal forum site, a poster said a friend tested a Fish carburetor versus a conventional unit on his 1961 Ford six-cylinder standard transmission station wagon. Over 1000 miles of testing with each carb, the Fish improved mileage by about 10 percent but at the cost of losing about 30 percent of the power as well as having less torque, affecting drivability.

How, then, can we explain the success that Fireball Roberts had with the Fish carb? Well, they do apparently work well at wide-open throttle, which also explains their popularity with period hot rods. The two Fish carbs that Roberts used had approximately 40 percent more venturi area than the stock four-barrels.

By the mid-1950s, carburetor design from major manufacturers like Holley, Carter, Stromberg, and Rochester had improved significantly. And, seeing as the Fish carburetor appears to have had some drawbacks in street-use vehicles, it’s understandable how it faded from the market via natural causes, so to speak. Combine Roberts’ success with a disappearing act and you have, ahem, fuel for conspiracy fancies about magical carburetors.

Please let us know about your favorite automotive urban legends, conspiracy theories, frauds, or hoaxes in the comments below!

Great Story! I’ve always thought the Ford floorboards from Drum Brake cases was clever. My son is 38 and an ASE Certified Master Technician. He is a big fan of the Fish Carbs due to their simplicity and the variable fuel delivery slot design. He currently runs a Fish Carb on his 1984 Land Rover Defender 90!

Wonderful story! I wouldn’t doubt the story being true. As frugal as Ford was, it could very well have happened.

During the summer of 1975, a co-worker told me of a magazine article about the young man in Texas, who had run his Briggs & Stratton lawn mower Engine on gasoline vapors, for an extended period of time. This began my personal journey of building and testing of a variety of home-made devices on several cars over the next ten years.

Several iterations were built but early results were disappointing, as I couldn’t vaporize the gasoline fast enough to power the six-cylinder Engine. I realized that producing a greater volume of vapor could be done by having a larger surface area (at ambient temperature) OR by heating the liquid gasoline in a smaller ‘container’.

My first truly scientific experiment allowed me to drive that ’65 Mustang to a friend’s house a few miles away. I made a copper Manifold which bolted in place of the 1100 Autolite Carburetor. It had two ‘butterfly valves’; one for throttle control and the other that I controlled from inside the car, which would allow a sort of mixture control, as it varied the supply of gas vapors vs ambient under-hood air, through the two openings. With an old fashioned 5-gallon gas can resting on the passenger floor, I ran some corrugated plastic tubing (think vacuum cleaner hose) out the window, under the car and up into the Engine Compartment, to feed the Manifold. I DID get funny looks as I drove past a restaurant. I suppose people thought I was asphyxiating myself…!

The Engine produced only enough power to attain 45 MPH, flat-out. But the worst part of that drive was the super-shrill scream coming from the air/vapor traveling through that plastic hose!!! With only 2 gallons of gas in the bottom of that 5-gallon can and the vapor hose being about 10 inches above the liquid level, it proved that vapor is what burns in an Engine’s Cylinders.

Another funny thing about that test was the smell of the exhaust gases, as it sat there running at idle. It smelled a LOT like propane exhaust smells.

Years of experimenting and numerous attempts at building a successful vapor fuel system demonstrated how terribly ‘fragile’ vapor is. Even after heating the liquid to a gaseous state, any restrictions or variations in flow velocity had a huge detrimental effect on KEEPING IT as a vapor before it was ingested into the Engine. My best effort before ceasing those experiments (being laid off meant no money to continue) was a 25% increase in MPG, with that six-cylinder Mustang (25 to 32 MPG). I did photograph some of these early builds, but in the seventies and eighties they were prints, not digital.

Cow magnets (1980)

I am indirectly partially responsible for the great cow magnet fiasco! 😉 My apologies.

A lot of years ago, got a call from a gentleman in Texas that had rust issues in his fuel and was going to take the car to the Pate show in a couple of days for sale, and could I overnight a rebuilt carburetor to him today?

Well, the answer was no, but; I told him about the Carter Magna-trap. This was a magnet with a special shape to fit into a Carter glass bowl fuel filter. I have told many enthusiasts about this, and suggested one of the refrigerator magnets like your better half uses to stick honey-do jobs to the refrigerator.

He told me he had a dairy farm, and had several of the cow magnets (cows are stupid, they will eat just about anything, including baling wire….oops, showing my age again ). If you feed one of the magnets to a cow, the wire doesn’t pass into the entire digestive tract (you city folks, use Google, not about to get into the digestive system of a bovine ) He would make a loop in the fuel line and tape three of the magnets to the loop, hopefully to stop the rust from passing into the carburetor.

About 3 days later he called, and he was laughing so hard, it took about 15 minutes for him to repeat the story. Seems everyone that looked at the engine asked about the cow magnets. After the first few, he started with a story that he continued to embellish as the day wore on. The final story was the magnets created a flux field, supercharging the fuel molecules, and giving almost non-Newtonian power and fuel economy!

Well, you guessed it. P.T. Barnum scores again! This even made the Johnny Carson show (remember the “headlines” segment)? Over 300,000 cow magnets were sold in the southwestern United States within a month. Every supplier was sold out, and had back orders.

Here is a link to a picture of the Carter Magnatrap that I placed on my website:

http://www.thecarburetorshop.com/Carter_Magnatrap.jpg

Newspaper story: https://www.washingtonpost.com/arch…noredirect=on&utm_term=.19601413ca5d

And now you know “the rest of the story” 😉

Jon.

What about the one where the government was unloading crates and crates of pickled new War II Willys Jeeps for $500? First come, first served. Get your name in quick! About the mid 70s?!