3 Automotive Urban Legends, Hoaxes, and Conspiracy Theories

Automobiles have been around for more than 120 years. It shouldn’t be surprising that, over that time, myths and lore have accumulated. Some of those stories are indeed true, like that of Henry Ford physically attacking the prototype of the restyled Model T that his son Edsel had commissioned on the sly. Others are fanciful and have that certain ring of urban legend, and there are even those stories alleged to involve dark secrets and conspiracies. Even paranoids can have actual enemies, of course, but most conspiracy theories deserve their association with headgear made of thin sheets of refined bauxite. However, as the rabbis of the Talmud taught, no lie can stand without a grain of truth to make it believable.

So without further delay, let’s look at three popular stories that are often repeated in various iterations as the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, that people swear happened to a friend of a friend of a friend. Enjoy the read, and then in the comments below, please tell us your favorite automotive urban legend, myth, or conspiracy theory.

Myth #1: Henry Ford’s Specifications for Parts Crates Allowed Him to Recycle the Wood as Floorboards

Our first tall tale has to do with Henry Ford, the subject of many such yarns. Allegedly, Ford Motor Company specified the size of crates used by component suppliers so the boxes could be carefully broken down and the wood panels repurposed as floorboards for Model Ts.

My favorite, rather elaborate, version of this story (elucidated here at the Jalopy Journal) hinges on what kind of plywood Ford used for floorboards. Of course, one commenter says, “the facts are true.”

Apparently, one of his outsource CEO’s got a call from Henry, not in regard to the product being sent to Ford, but the containers they were being shipped in. Ford started growling at the guy that the boxes were unacceptable and needed to be changed IMMEDIATELY! Ford then gave the fellow instruction on what type of wood to use, new dimensions, AND where to drill the holes and what type screws to use.

Now, as soon as the gentleman was off the phone with Henry, he was back on with of Ford’s execs, along the lines of, “the guy has finally cracked, etc”.

Well, the day came for the first shipment to arrive. Ford came down to the loading dock, with a train of exec’s waiting to see whether or not Ol’ Henry was ready for the happy farm… Ford asked one of his employees to move one of the boxes over to the assembly line, took off his jacket, unscrewed one of the boxes and put the board onto a chassis that was on the line.

I know that I embellished a bit (been a while since I’ve heard the story), and I don’t know what year it was, but the facts are true—Ford got free floorboards out of his supplier.

In reality, not much of that story is true, although Ford did use a lot of wood in making the Model T. It’s estimated that each Model T used about 100 board feet of lumber—for the floorboard, toeboard, dashboard, spokes for the “artillery” style wheels, and a wooden frame for the body’s steel panels.

Also, after the Dodge brothers (who were his primary supplier) parted with Ford, Ford Motor Company developed into one of the most vertically integrated manufacturing firms in history. Eventually, FoMoCo made its own steel from ore mined from its own mines, its own glass, and Henry even tried growing his own rubber trees in the Amazon. There was a period when Ford didn’t have that many outside suppliers. Because of his need for wood Ford owned about a half-million acres of forest in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, along with three lumber mills as well as a large industrial facility in Iron Mountain for milling that wood into usable parts. If anyone was making wood crates for Ford parts, it was Ford. Those wood crates, however, were not recycled into floorboards. There was a special department at the Rouge facility for recycling that wood into other crates.

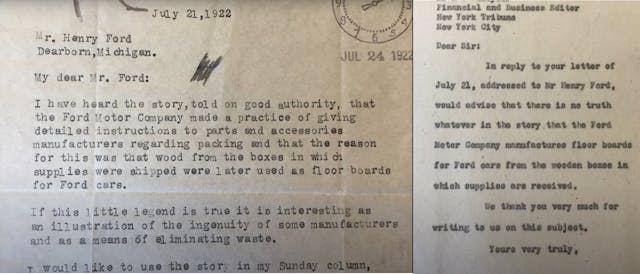

The urban legend dates back over a century. In fact, in 1922, the financial and business editor of the New York Tribune wrote Henry Ford to verify the story and Edsel Ford’s office replied, saying there was “no truth whatever” in the story.

One part of the story that is true: Henry Ford was very much into recycling. The Iron Mountain facility didn’t just make wood parts (and bodies for “woodie” station wagons and eventually military gliders during WWII as well). It processed sawdust, wood scraps, and other waste materials into usable materials like methanol, creosote, and charcoal briquettes.

Myth #2: GM Bought Up Streetcar Companies to Kill Public Transportation and Sell More Cars

The idea of big corporations conspiring to increase profits at the public’s expense is an easy one to sell to credulous people, even some who are initially skeptical.

This particular conspiracy theory has been amplified by Hollywood, via the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and on public television through the documentary Taken for a Ride. Here’s how it goes: In the mid-20th century, American cities had inexpensive, efficient, and convenient public transportation provided by streetcars running on rails and powered by overhead cables. General Motors changed all that when it bought up streetcar companies and purposefully stymied them by increasing fares and decreasing service. All of this was supposedly a step in ultimately replacing them with buses that were more profitable to GM, but less convenient to riders. In turn, the add-on effect would be to persuade now-unhappy public transportation riders to switch to privately owned automobiles.

We actually know the origin of this conspiracy theory. Fifty years ago, a newly hired attorney named Bradford Snell, working for the U.S. Senate on antitrust matters, testified that the government had criminally charged “…General Motors and allied highway interests for their involvement in the destruction of 100 electric rail…systems… throughout the country.”

Snell further said that a “federal jury convicted GM of having criminally conspired with…others to replace electric transportation with gas or diesel-powered buses,” and that the streetcar systems had been “vastly superior” in terms of speed and comfort to the internal-combustion-engine-powered buses that took their place.

Snell concluded,

“The noisy, foul-smelling buses turned earlier patrons of the high-speed rail systems away from public transit, and, in effect, sold millions of private automobiles…General Motors’ destruction of electric transit systems across the country left millions of urban residents without an attractive alternative to automotive travel.”

Let’s break this down. It’s indeed a historical fact that the General Motors-affiliated companies (with investments from Firestone, Standard Oil and other companies in the oil and transportation sectors) National City Lines and Pacific City Lines started to purchase municipal trolley systems starting in the late 1930s. It’s also a fact that, in a few short years, those streetcar lines went out of business, to be replaced by municipal bus lines. As well, it’s a historical fact that GM, Pacific City, and other firms were indicted in 1947 for conspiring to monopolize the interstate sale of buses, fuel, tires, and other supplies to their captured transportation companies, as well as conspiring to form a transportation monopoly. While most of those companies were convicted on charges of monopolizing the sale of buses and related materials, they were acquitted of the charge of trying to monopolize transportation in general.

Transportation Quarterly is an academic journal published by the non-partisan Eno Transportation Foundation. In 1997 it published a paper by Cliff Slater titled General Motors and the Demise of Streetcars arguing that there was no conspiracy. Slater argued that the trolley systems were replaced by buses for strictly economic reasons. Buses were cheaper to run than streetcars and were much less expensive to implement because they didn’t need railways. Cities and suburbs were expanding rapidly, and it was much easier, cheaper, and faster to simply add another bus stop on existing roads, rather than extend the rails.

The paper further asserts that it wasn’t the death of streetcars that increased private car ownership; it was the other way around. Before the popularization of the private automobile, if you wanted to get to work on time, you took pains to live within a 30-minute walk of a streetcar line. The convenience of driving directly to one’s destination in privacy and comfort won out over taking a crowded trolley and then having to walk blocks from the trolley stop to one’s final destination. Additionally, having a private automobile makes shopping and carrying home your purchases more convenient.

In 2010, CBS’s Mark Henricks reported:

There is no question that a GM-controlled entity called National City Lines did buy a number of municipal trolley car systems. And it’s beyond doubt that, before too many years went by, those street car operations were closed down. It’s also true that GM was convicted in a post-war trial of conspiring to monopolize the market for transportation equipment and supplies sold to local bus companies. What’s not true is that the explanation for these events is a nefarious plot to trade private corporate profits for viable public transportation.

Myth #3: The 200-Mile-Per-Gallon Carburetor

This myth also has to do with alleged suppression. In this case, oil and car companies supposedly kept a highly efficient carburetor off of the market.

In truth there are, ahem, manifold reasons why the auto industry moved away from carburetors and embraced electronic fuel injection. Controlling emissions was probably the, ahem, driving factor but the simple fact is that fuel injection works better. (Editor’s Note: Ronnie’s throat-clearing quota has been reached. One more and we pay him in lozenges.) What’s surprising is that despite the indisputable superiority of fuel injection, stories about miracle carburetors continue circulating to this day. What’s not surprising is that, despite the change in technology, there are still dubious fuel-saving devices on the marke. Many claim to work via your car’s OBD II port or even the 12V power socket.

As with other urban legends and conspiracy theories, this one has a compelling story. Variations abound.

Here’s the gist: Someone takes delivery of a car from a major automaker. In some versions it’s a retirement gift from the company, in others a couple arranges for a factory delivery. They are shocked to discover that the car achieves unheard-of fuel economy. In some tellings, it’s 100 mpg; in others, it’s as much as 200. Of course, nobody can ever prove it because these stories usually end in one of four conspiracy-laden ways:

- Mysterious men show up, pop the hood, make a few adjustments and the magical mileage returns to normal.

- The automaker recalls the car. It is either replaced by another car or the original car is returned, minus the unusually efficient gas mileage.

- Guys in suits with briefcases of cash show up and make an offer that can’t be refused.

- The car is stolen or otherwise disappears overnight.

The popularity of this particular urban legend has arguably tilled fertile ground for scam artists promoting dubious inventions. You may have heard of scams such as the “Fish Carburetor.” To make matters more confusing, while there have been multiple cases of such fraudulent products, there was a genuine, non-scam Fish carburetor.

We’ll get to the real-deal Fish carb in a moment, but first, let’s look at the Pogue carburetor. The Pogue’s story contains many elements essential to nonsense narratives of this type, though I think the story might be best characterized as a hoax, rather than a scam, since no money or products ever changed hands.

Charles Nelson Pogue (1897-1985) was a mechanic and inventor from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. From 1927 to 1934, Pogue successfully filed for four carburetor patents, U.S. patent 1,750,354, U.S. patent 1,938,497, U.S. patent 1,997,497, and U.S. patent 2,026,798. While some reports describe Pogue’s carburetors as catalytic, none of the patents mention the use of catalysts. What the patents do mention is vaporization. Some context: One problem that affected early carburetors was an inability to fully aerosolize fuel, resulting in small drops of liquid fuel remaining unburned. If you could better vaporize the fuel, people deduced, you’d get more power and better fuel economy because of more complete combustion.

In 1936, the Canadian Automotive Trade magazine reported that a car equipped with the new carb was able to travel 1879 miles on just 14.5 gallons of gasoline. (That works out to 129.5 mpg.) A Winnipeg car dealership manager claimed to have achieved 217 mpg after fitting a Pogue carburetor to his car. Another dealer claimed to have gone 26 miles on just one pint, which is 208 mpg. As the stories spread through Canada, the reports and rumors proliferated.

To his credit, Pogue denied these reports. Some said that thieves had broken into Pogue’s shop and had stolen some of his carburetors to either discover its secrets and/or suppress its production. Wealthy Canadian backers were rumored to be negotiating with Pogue for the rights but the deals somehow never came to fruition. Some believed Ford of Canada had bought the rights to the technology.

P.M. Heldt, the engineering editor of Automotive Industries magazine during that period, in regard to a diagram of the Pogue carburetor, said, “The sketch fails to show any features hitherto unknown in carburetor practice, and absolutely gives no warrant for crediting the remarkable results claimed.”

Critics wanted to see the miracle carburetor, but Pogue apparently never demonstrated a working version, nor did his carburetor ever see series production. Of course, as these things go, the fact that the Pogue carb never saw the light of day is pointed to as further evidence of the conspiracy to suppress it. Thus, the story continues to be perpetuated. The fact that there is no record of Pogue ever assigning rights to his patents to anyone, including car and oil companies, doesn’t get as much air among conspiracy theorists.

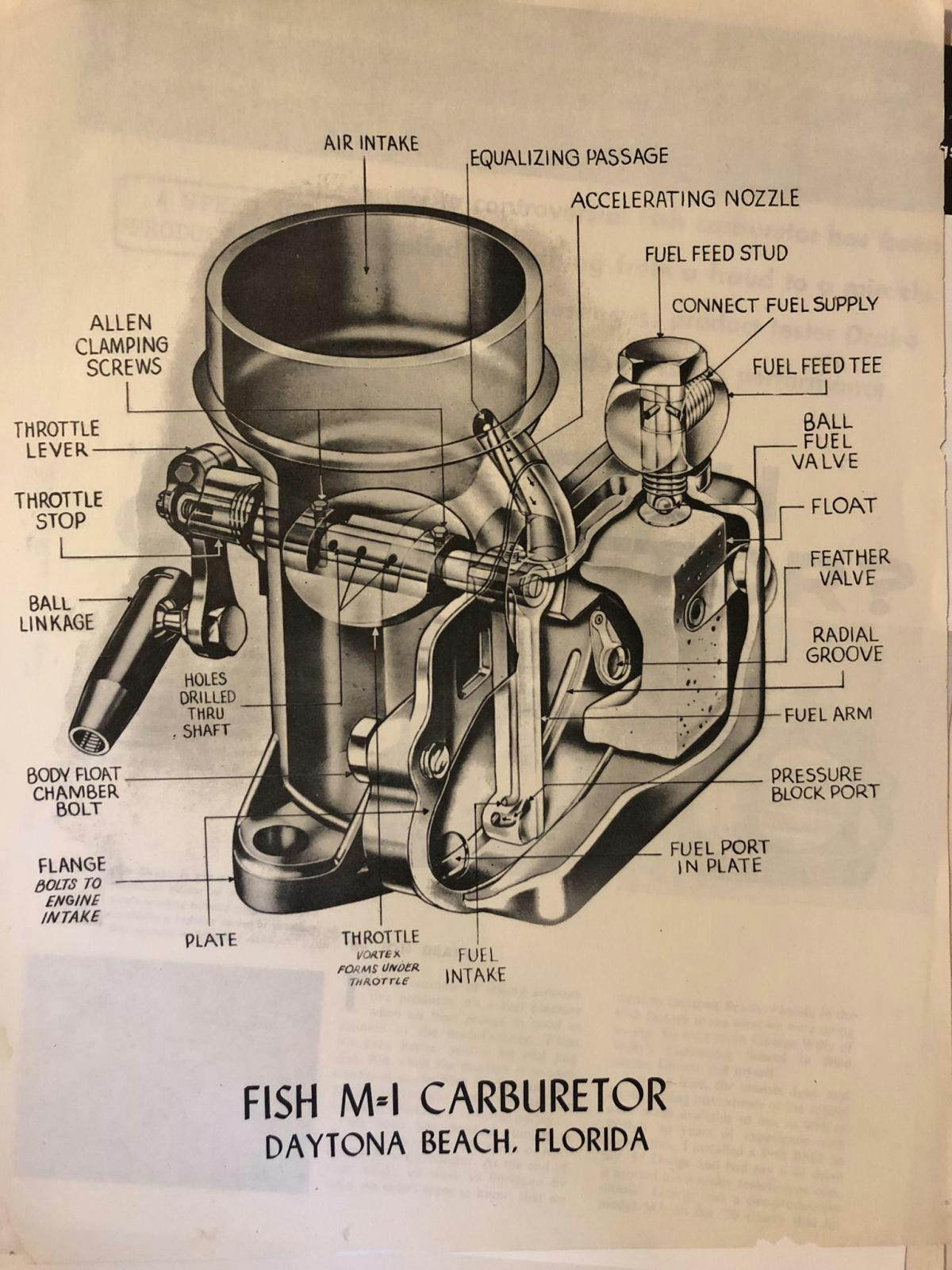

Unlike the Pogue carburetor, the Fish Carburetor Company actually produced working carburetors—over 125,000 of them from 1947 to 1959. Invented by hot rodder John Robert Fish in the early 1930s, and protected by three U.S. patents, the Fish design was meant to solve the problem of carburetors’ float chambers. Carburetors use a float chamber to meter fuel to the jets; the chamber fills with fuel and a float attached to a valve shuts off the fuel when the chamber is filled. Acceleration, cornering, and braking forces can affect the position of both the float and the fuel, interfering with fuel delivery and causing drivability issues.

The original intention of the Fish carburetor was to avoid the weaknesses of the float chamber and its sensitivity to the forces of acceleration and cornering. The sources I found give two different descriptions of how Fish’s invention worked: One source says that the carb operates on pressure differential—not air speed. The other says that it sensed the mass of the airflow rather than the volume. Either way, the Fish device was said to be self-adjusting and self-compensating to changes in weather or altitude. The Fish design also did away with accelerator pumps with a clever ram air design.

Instead of the single jet of conventional units, the Fish carb delivered fuel using six to ten jets built into the throttle spindle, which was said to produce better fuel atomization and vaporization, thus improving fuel economy, power, and cold-weather starting. Fish claimed 20 percent better fuel economy and 30 percent more horsepower when compared to conventional carburetors.

The Fish carb got a publicity boost when stock car legend Fireball Roberts swapped out the OEM four-barrel carb in his Hudson Hornet racer for a couple of Fish units, to some success. The Fish induction system became popular in the early days of stock car racing.

Now here’s where the Fish story gets a little bit, ahem, fishy. (Editor’s Note: So will it be Halls or Ricola?) Supposedly, original equipment carburetor makers conspired to put Fish out of business. Fireball Roberts was said to have done well in qualifying, but somehow his tires never lasted the way they did for factory-supported stock car teams. The United States Post Office allegedly started marking all of Fish’s shipments “FRAUDULENT,” returning them to sender with claims that the carburetors were not actually being produced. (That’s a little bit odd considering that there’s an archival photo of the production line in Daytona.)

It’s worth remembering that the era in which Bob Fish was operating was one during which time federal bureaucrats and prosecutors effectively put Preston Tucker out of business, though a jury acquitted him and his associates of any wrongdoing. It thus seems possible that overzealous postal inspectors, concerned about gas-saving gadget scams, targeted an innocent company.

The way the story goes, the Post Office’s actions resulted in the carburetor’s rights being reassigned to a Canadian company, which sold them outside of the United States.

The Fish carburetor truly did develop a following in the hot rod community, and the Brown Carburetor Company of Draper, Utah put it back into production, making about 10,000 new Fish-design carburetors from 1981 to 1996.

On the Jalopy Journal forum site, a poster said a friend tested a Fish carburetor versus a conventional unit on his 1961 Ford six-cylinder standard transmission station wagon. Over 1000 miles of testing with each carb, the Fish improved mileage by about 10 percent but at the cost of losing about 30 percent of the power as well as having less torque, affecting drivability.

How, then, can we explain the success that Fireball Roberts had with the Fish carb? Well, they do apparently work well at wide-open throttle, which also explains their popularity with period hot rods. The two Fish carbs that Roberts used had approximately 40 percent more venturi area than the stock four-barrels.

By the mid-1950s, carburetor design from major manufacturers like Holley, Carter, Stromberg, and Rochester had improved significantly. And, seeing as the Fish carburetor appears to have had some drawbacks in street-use vehicles, it’s understandable how it faded from the market via natural causes, so to speak. Combine Roberts’ success with a disappearing act and you have, ahem, fuel for conspiracy fancies about magical carburetors.

Please let us know about your favorite automotive urban legends, conspiracy theories, frauds, or hoaxes in the comments below!

Even to this day in the Los Angeles area people still talk about the conspiracy to eliminate the electric Red Cars trolleys by the big oil and tire companies and GM busses. A few years ago a local PBS station put on a documentary about the demise of the “Red Cars”. Fact is the numerous lines LOST MONEY almost every year! The cars were hot in the summer and cold in the Winter and SLOOOW! Many ran on tracks on main streets and would be delayed by automobiles clogging the streets. Fact is people then AS TODAY thought the “public transportation” was unpleasant and inconvenient. As automobile ownership increased the street cars lines lost even more money and local government looked for ways to eliminate the budget drain. Fact is FEW missed the street cars, yet today the myth of fast cheap public transportation persists. Today public transportation is still a miserable failure in Los Angeles, yet the “get rid of automobiles” crowd persists. It still losses money, takes longer than sitting in rush hour traffic and NOW there is a lot of crime on the subways and busses!! After the local news started airing weekly incidents of crime and attacks on passengers AND THE BUS DRIVERS, now a lot of money will be spent on hiring transit police! More money down the drain – yet FEW in Los Angeles want to ride public transportation.

In the late 60’s, I saw Bill Lear come on a TV show talk show one night with an aluminum steam engine. He said there was a car version with 100 HP and a bus version with 200 HP, but extremely high torque. I could run on anything flammable. People didn’t believe me for a long time, saying it was an urban myth. With the Internet, I found that I was right, it was a failed project of his that was actually tested in a bus. Did not do well. Too bad.

My 1966 Chevrolet had a 2 barrel, was rated at 160 HP, and got 17 MPG. A little build and a small Edelbrock 4-barrel changed it to 250 HP, and the 5-speed means it will cruise on the highway at 29 MPG. I’ll never make the investment back, but I feel pretty good about it just the same. No magic, no secrets.

What I always liked about the carburetor story is that those who tell it always know who it was that invented it. Something like “my 4th cousins next door neighbors brothers plumbers dad.”

I ask if they have ever read anything about the necessary stoichiometric ratio that an engine must have in order to not burn holes in the pistons. “Stokeo what?” If it was all that easy, you could just put in smaller jets and reap the benefits right? At least until it burned a hole in a piston a mile down the road.

And then, if some automaker came out tomorrow (assuming anyone still used carburetors) and said “yes there is such a thing as a 200 mpg carburetor and we feel bad about paying all of these ‘gas guzzler’ fines so we are going to have a genuine guaranteed 200 mpg truck at the dealers tomorrow.” The resulting sales would eclipse the introduction of the Mustang.

Sometimes the laws of physics take all the fun out of life.

Rant off

How about Somkey Yunick (I hope I’m spelling that correctly) he built a car (I think a Chevy Chevette) that got 70 to 80 mpg and it was written up in Car Craft or Hot Rod magazine in the 80’s or 90’s

Good, you got Yunick right! Smokey was his nickname, apparently (I read) because of his old black pipe.

It was a Pontiac Fiero and it averaged 40 mpg and produced over 200hp being driven aggressively. You can see the article in hot rod archives I believe it is around 1981. It involved usin a small turbo for pressure and high heat to vaporize the fuel. The Garlits Museum has a replica car with the original engine in it. You can also view the patents online.

I seem to recall ads in Popular Mechanics for the “water carburetor”. This device was, somehow, to extract hydrogen from the water supply (fuel) and, viola’, you had free fuel. These ads were in the late 50’s early to mid-60’s magazines. Even as a kid, the premise didn’t seem very possible. Of course, every other edition of the “mechanical science magazines” of the period were full of promises of “flying cars” for everyone, or, business men in suits “jet packing” their way to the office. I have wondered if anyone ever bought this product.

Two myths that seem to still be heard:

1) It crystallized and broke. Uhh, all metals are crystal structure. What is likely to support this myth is a broken part might have a crystalline appearance. But the metal did not crystallize, it was that way from the beginning.

2) Storing a battery on the concrete floor. New plastic batteries are insulated from any effects, Even more comical about the concrete floor myth is that a metal battery tray is countless more conductive than any slightly damp concrete floor.

Two for the mileage myths:

1) The vortex generator inside the air cleaner. It was a set of vanes that supposedly directed the air to better mix the fuel in the carburetor.

2) A related item to this was the fan blades in a carb spacer under the carburetor. Same basic theory, to help vaporize the fuel better. The fan blades were not powered, just free spinning.

#2 was the ‘Mini-Supercharger’ advertised for forty years, and often it came with optional (spendy) water-injection, which could actually have benefits. See my other comments. Mike Lamm, in SIA, ‘Schock’ said that the vanes probably just impeded the flow of he vaporized mixture, and hurt economy/performance. I’d also suspect that they provided a ready source of vacuum leaks, too!

Terry,

Being in the battery business for over 20 years I’ve heard the “don’t store a (lead acid) battery on concrete, it’ll discharge it” claim, and have often wondered if it were true. I’ve come to accept that there may be an element of truth in the claim. It has to do with the batteries internal temperature; the lower the temperature, the lower the output. Concrete is usually colder than air temperature and a battery set flat on the floor will provide a path for the concrete to pull heat from the battery; resulting in a lower capacity.

Thanks. I always wondered why that would be the case.

I sure wish that Smokey Yunick was still around. He would have a lot to say about the Fish Carburetor as his shop was right there in Daytona Beach back then.

Bob, one item I interviewed Smokey on was the old Chevy W-motor (348-409 & a few 427’s) back in the ‘seventies. Asked ‘what kind of engine was the W?’ he just said ‘Junk!’ He was a 283 man.

Also, one urban legend that refuses to die is that the W-motor (watch the semantics, here!) was a ‘truck motor.’ The contention was that it was designed for heavy-duty commercials, but pressed into service in automobiles in 1958 because the new Impalas were weightier and more heavily optioned than previous Chevys. Yes, the 348-409 equipped that brands new truck as an option, but no; it was designed for and introduced in both vehicle lines simultaneously. The Chevy engine that came out in trucks first was the old 235 six, which replaced the Stovebolt 216 in PowerGlide cars first, then in all Chevys by 1953; it debuted about 1941, I believe. The W lingered longer in commercials, dying out after 1965, tho. So, while it was a ‘truck engine’, so was the original SBC 265; I drove a ’56 Chevy Forest Service Class III Tanker that had the original 265 back in ’64-5. The 235 (or long-stroke 292!) was a better truck engine. I not only researched the W in the GM paper written for the SAE Journal, but interviewed two of the engineers who wrote it, including Harry Barr when he was boss of Buick! But try telling an Impala guy the facts… !!

A few facts :

The Chevy 216CID engine with non pressure rod bearing lubrication lasted through the 1953 model year .

The 1954 235CID engine had fully pressurized oiling through out and was a one year wonder, good luck finding the correct cylinder head today .

The 235 CID truck engine was also in the Chevy light & medium duty trucks as an option, it too had no pressurized rod bearings (“Target Lubrication !”) .

In… 1955 (IIRC) the truck version of the 235 for the medium duty trucks was the 261 CID, it had many different if interchangeable parts with the 235 .

The 292 engine is a ‘thinwall’ design and has nothing at all to do with the world famous “Stovebolt” 216’s & 235’s .

-Nate

I love the miracle mpg carburetor. Now I can get a thing that plus into my 12V socket and aligns the electricity to produce better spark/combustion and miracle mpg’s! :^)

“Red Cars Are Cop Magnets.”

I love this one because, although I can’t find any data to support it (and I can find some date to disprove it), even people in the industry tend to quote the red-car myth.

I recently bought a used bright yellow sports car at a dealership (because it was on sale, not because I adored the color). I half-jokingly said I was a bit concerned that it was too conspicuous and cops would pull me over a lot. The sales person answered, immediately and without blinking: no, that only happens with red cars. You should be safe.

“Arrest-me Red”? “Hello Officer Red”?

My bile-yellow 1972 240Z got pulled over often enough. Once by a young sheriff whose beef was the CA license plate was too faded to easily be read. Making me almost late for my class of Kindergartners, I told him to cite me or let it go, and he gave in. It was a terrible color, tho! I painted it ‘Japanese Racing Green, code 907″ eventually.

Well, we’ll see how I do with yellow cars and tickets. Funny, the yellow car I was talking about above is a 2023 Z, and I also have a 1972 yellow Fiat 850 Spider, which I got on auction here. We have yellow in common in two ways. Yellow seems to choose me lately.

They still teach as fact GM buying the trolly system and pulling up the rails in college. I had a public policy class in grad school where it was presented as fact.

I’ve always been told the three great lies were:

1. I’ll respect you in the morning.

2. The check’s in the mail.

3. I won’t ______in your _______!

The Diesel Volkswagen Rabbit: 1982 not ‘72?

I am a firm believer that there were high efficiency carbs built and tested but that fuel companies who were king at the time were not fond of the idea that the car companies who cut down on their sales numbers. I also believe it as I witnessed a tale first hand in the 70s. Good friends of my parents lived in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia Canada. The gentleman at the heart of this was a business owner and leading citizen in his community. Lions club and all. As this man’s moving and storage company did well (Allied Van Lines franchise) our friend often had new cars, later only Cadillacs. I don’t recall what make of car (might have been a Ford or Mercury product) he had purchased at this point in the early 70s but our friend was a big man in stature so he drove big V8 sedans. Over dinner one night he told us how much he was loving his new car. He said it was quiet and comfortable and had lots of power for the highway. He also said he had started figuring out his gas mileage as he had never owned a car that got the kind of mileage this car was getting. I don’t recall the exact numbers and they were no where near claims of 100-200 mpg etc. but I do recall my dad being shocked that this big block big American sedan got considerably better fuel mileage than dad’s 307 powered ’71 Chevelle. Like in the 30 + mpg territory.

Long story short (too late) our friend enjoyed his exceptional fuel mileage until his second warranty service. He said nothing on the first visit to the dealer as he had no complaints and it was just the usual oil and lube 1st warranty visit of the time. Alas on the second visit he commented on drop-off how very pleased he was with the fuel consumption and that head office should be proud. He got a call later informing him that the warranty guy had to keep the car a bit longer to do some adjusting and tuning and then it would be returned. Of course after that service what our friend got back was a big sedan that ran very well as always but now averaged a normal 12-15 mpg like any other big US car. and yes the car had enough dust under hood to make it obvious that the only spotlessly clean place under the hood was the air filter assembly and the carburetor looked even newer than the car which now had a few K miles on it. What can I say. I heard it first hand and saw the car in the driveway.

Never leave your new car at an indoor parking lot in New York City. They’ll switch out your engine (transmission….) with an older car and you’ll never know.