10 Hybrids That Helped Pave the Road to Popularity

When the Toyota Prius went on sale in Japan in 1997 and in America in 2000, what seemed like a revolutionary idea was, in fact, a century old. Using an electric motor to reduce the amount of fuel used seemed to make sense. Making it work was another story. Many attempted and all failed for a century due to a lack of consumer interest. These days, automakers and consumers are turning to the long-spurned technology as a bridge between internal-combustion-engine powertrains and full battery-electric vehicles.

1900 Lohner-Porsche

By now, everyone knows that the first attempt at building a gas-electric hybrid car was made by 25-year-old Ferdinand Porsche. The world’s first gas-electric hybrid was designed for Hofwagenfabrik Ludwig Lohner & Co., following the launch of the the Lohner-Porsche Electromobile at the 1900 Paris Exposition. The Lohner-Porsche Electromobile used a 2.5-horsepower motor placed in each front wheel, which provided a top speed of 23 mph.

As a follow-up, Porsche designed the Semper Vivus, Latin for “always alive.” The series hybrid used the Electromobile’s electric motors to drive the wheels. But their energy came from a generator powered by two water-cooled 3.5-hp DeDion Bouton internal-combustion engines. It debuted in 1901 as the Lohner-Porsche Mixte. Despite marketing attempts to garner interest, such as shuttling Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand during a military maneuver, a mere 11 Mixte hybrids were sold between 1900 and 1905.

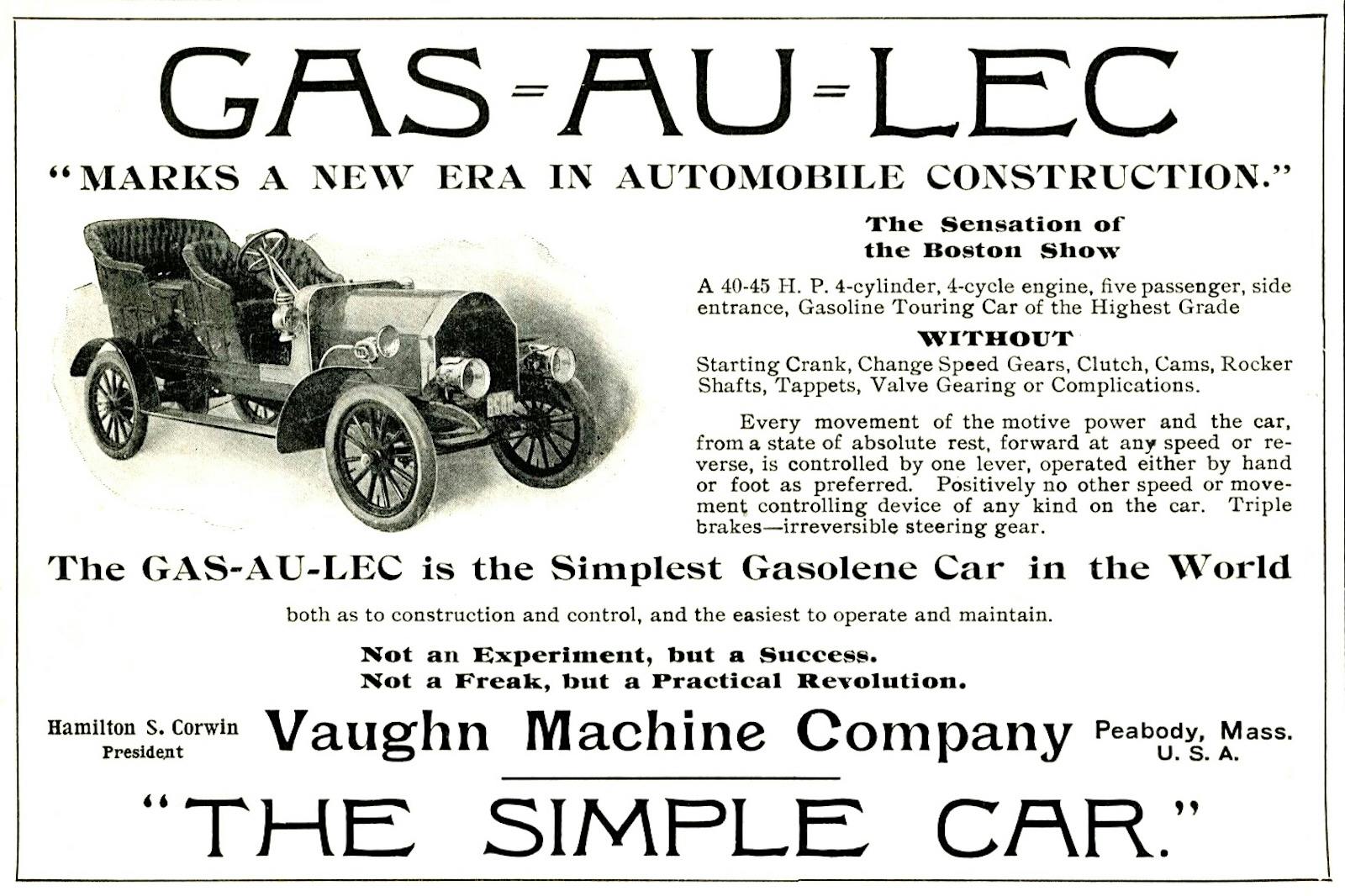

1905–06 Gas-Au-Lec

Deriving its name from a combination of the words “gasoline,” “auxiliary,” and “electric,” this vehicle was built by the Vaughn Machine Company of Peabody, Massachusetts. It combined a 40-horsepower T-head four-cylinder engine with an electric motor, the latter providing power for starting and reverse as well as low speeds. Otherwise, it worked as an ordinary gasoline car. In 1906, Hamilton Corwin, Vaughn’s president, stated that the Gas-Au-Lec was “not a freak, but a practical revolution.” The company proudly proclaimed the car’s lack of a “starting crank, change speed gears, clutch, cams, rocker shafts, tappets, valve gearing or complications,” adding that the car was “not an experiment, but a success.” Not quite. The marketing did little to attract interest, and production of the Gas-Au-Lec amounted to just four cars.

1916 Owen Magnetic

Produced in New York City, Cleveland, and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, the Owens Magnetic was built by the Baker/Rauch & Lang companies and used an electric transmission. Its driveshaft and engine were not mechanically connected. Instead of using a flywheel, the motor’s field coils rotated around a propshaft, creating an electric field that produced current that was sent to a generator, which turned the driveshaft. Its 24-volt electric system could propel the car at low speeds, as well as start the car and provide lighting. Not surprisingly, these complicated cars were pricey, and they attracted such celebrities as Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso. Some 974 units were built through 1921.

1916 Woods Dual Power

The Woods Motor Vehicle Company of Chicago had survived building electric cars since 1899. But by 1915, electric car demand was had declined. In response, the company developed the Woods Dual Power. The gas engine idled up to 15 mph, letting the Woods electric motor drive the vehicle. After that, the gas engine took over. Top speed was 35 mph. But the car proved troublesome, and it was revised the following year using a larger 1.1-liter Continental four-cylinder gas engine. By 1918, however, Woods was history.

1928 Gas-Electric

Although transit companies had experimented with gas-electric hybrid buses, cars were another story altogether. Enter Mitten Management, a family business that controlled the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company for decades. In 1928, as Thomas Mitten’s son Arthur assumed control of the P.R.T., the transit company built an experimental gas-electric taxicab using a Willys-Knight 70A chassis and its sleeve-valve engine mated to a General Electric motor. A prototype was built, but not much else is known about the car, as it was never produced, for P.R.T.’s fortunes had turned and Thomas Mitten would be dead within a year, after the City of Philadelphia launched an investigation into his personal finances.

1969 General Motors XP 512

GM tasked its engineers and stylists with creating small vehicles with minimum weight, low operating expense, and low emission levels. One of the five vehicles they developed was the XP 512, a Lilliputian car with a 50-inch wheelbase, 66-inch length, 56-inch height, and 52-inch width. Weighing a mere 1250 pounds, it was a front-entry vehicle that seated two and their stuff. Built using aluminum panels over a tubular frame, it was powered by a 12-cubic-inch gasoline engine and a DC electric motor that worked through an electro-magnetic clutch.

Rated at 13.8 horsepower, top speed was 35 mph. It had a 5.2-mile range at 30 mph and a 150-mile hybrid range using three gallons of gasoline.

Electric energy came from a 72-volt power battery pack and a 12-volt accessory battery. The XP 512 ran on electricity up to 10 mph, after which the driveline worked like a traditional hybrid. Its battery pack was recharged by a 90-volt Delcotron generator using the gas engine, but it could also be plugged into a 115-volt outlet for recharging, although GM didn’t reveal how long that would take.

1979 Fiat 131 Ibrido

Debuting in Detroit, the Fiat 131 Ibrido—Italian for “hybrid”—was an experimental version of the car sold stateside as the Fiat Brava. Powered by the Fiat 127’s 903-cc four-cylinder gas engine detuned to 33 horsepower, it was mated to a 26-horsepower, 24-kWh electric motor. With lead-acid batteries filling its trunk, the Fiat 131 Ibrido had a top speed of 75 mph. But don’t think for a minute that it was quick; the run from 0 to 60 mph took 27 seconds. And it wasn’t fuel-efficient, either, returning 22.8 mpg. Fiat’s hybrid gas engine ran constantly; its electric motor came on under heavy torque demand. But remember that name: Online reports suggest a Fiat 500 Ibrido is due to go on sale by early 2026.

1980 Briggs & Stratton Hybrid

In 1978, Briggs & Stratton hoped to show that traveling at the 55-mph national speed limit could be accomplished far more efficiently with an air-cooled and carbureted flat-two engine producing a mere 18 horsepower from just 694 cc. The resulting six-wheel hybrid used 12 six-volt lead-acid batteries to power one of the rear axles, endowing the 3200-pound hybrid a pure electric range of about 45 miles. Wrapped in a design created by Brooks and Dave Stevens, the hybrid used many Ford Pinto and Volkswagen Scirocco parts. As you know doubt know, it never made it past the concept stage.

1981 General Electric HTV-1

In April 1980, the U.S. Department of Energy awarded an $8 million, 30-month contract to General Electric to develop a gas-electric hybrid car in an effort to cut fuel consumption. Dubbed the HTV-1, or Hybrid Test Vehicle, its 44-horsepower electric motor powered the car up to 30 mph, whereupon the 60-horsepower four-cylinder gas engine took over. The drive funneled its power through a four-speed automatic transmission to the front wheels. Electric power came from 10 lead-acid batteries, with the hybrid adding 800 pounds of weight. Perhaps this is why running 0–56 mph required 12.6 seconds, although that wasn’t so bad by the standards of the day.

1989 Audi Duo

The 1989 Audi Duo concept vehicle, which was based on an Audi 100 Avant, was Audi’s first foray into hybrid technology. It debuted at the 1990 Geneva motor show, and the front wheels were powered by a 134-horsepower, 2.3-liter five-cylinder gasoline engine, while the back wheels were powered by a 12-horsepower Siemens electric motor that ran on a part-time basis. Electric energy came from a trunk-mounted, 9-kWh nickel-cadmium battery, and the two powertrains worked together. However, if you wanted to drive in EV mode, you had to stop the car and shift into neutral. But you could only drive 24 miles—and no faster than 31 mph.

As much as this is a good example of lost and forgotten in the hybrid category I always think of diesel- electric trains as the example of a proven technology that works and can/has been translated . If I’m not mistaken they predate hybrid autos by a significant amount as well as having been reliably in service for more than quite a few years before the first Prius hit Americas shores.

The difference is that locomotives don’t have batteries to recover energy and store it for later use.

The primary reason that modern locomotives are diesel-electric is because it is easier to transmit and multiply torque electrically instead of mechanically.

As a teenager, I was fascinated with steam power and did some checking into this. The primary reason modern locos are diesel-electric is that they require roughly 1/3 the amount of maintenance that a steamer needs. When you also consider the infrastructure needed for steam (fueling stations, water stations, “helper” engines, and “pufferbillies”), conversion was a no-brainer for most countries.

Was kinda wash between the diesels and steam. The old saying that it took one day to find the problem and seven days to fix the steamer, and seven days to find the problem with the diesel and one day to fix it. At least as so I was told.

I was specifically noting that the reason they were series diesel-electric and not pure diesel.

As for diesel electric trains, you have to remember that they only run on 1% max grade tracks. That is the spec. for grade and have the right of way. Now only if roads were built the same way the fuel economy of our cars would be outrageous.

I may be in the minority here but I find most automotive hybrid useless.

Unless you really are just bend on saving the planet there is no up side.

They cost more to buy, They cost more to repair, The fuel savings is seldom enough to cover the added cost of repair and purchase. By the time they need a battery often many are not worth the cost of the replacement and the labor. You still have all the ICE repairs and service. Resale on older models in need of battery or work is a killer.

The Prius with the small battery is one that is not bad to repair. Many others do not fair as well.

I’m ok with the front drive on the Corvette as it is there for a reason of performance and eliminating the drive shafts and differential.

If I wanted electric I would just go and do the full EV and be done with it or stick to ICE.

I agree with you. Hybrid always seemed to be an interim solution until battery technology improved to such a point that EV would be viable for 80% of situations. Now that we are there, or thereabouts, there seems to be a real lack of confidence to make the switch. You don’t get the full benefits of EV when you are dragging a generator around with you (an oversimplification but you get the point).

Think about all those EV “advantages” while you wait at some charging station for however long while the hybrid guy fills up & drives off in less than 10 minutes including going in & getting a snack for the road!

I agree, Until you can recharge an ev in 10 minutes, They will always be at a disadvantage. Now that Toyota has several cars that are pushing 50 mpg or more, I am looking into buying one. Less wear on brakes and decent performance they are not race cars but are practical cars

Dangit, that XP 512 is so bad I actually want one! Can you imagine how fun that would be at car shows?

Scout and Geo. – Yes it’s different but I’m sure you’d both easily agree that many of the lessons apply. Much like going from steam to diesel had definite advantages, going from piston driven aircraft engines to jet even in commercial applications had significant advantages especially in terms fuel (burns more cost less) and especially maintenance costs. GM Electro Motive became a major player in the game as did GE. Like technologies do have a way of finding and benefiting from each other don’t they?

The 1969 General Motors XP 512 seems like a terrible penalty box to have been in. Not surprised it never happened.

“…but it could also be plugged into a 115-volt outlet for recharging, although GM didn’t reveal how long that would take.” GM’s website says “Complete recharge from a 115-volt household outlet requires 7 hours. The car’s range at 25 miles an hour is 58 miles.” https://www.gm.com/heritage/collection/gm-concept/1969-512-electric-experimental

IMHO electric cars are dead in the water until a battery can be developed that will give comparable ranges to gas cars and batteries that will actually work in cold climates or at least to have a convenient charging infrastructure . Other wise there just not practical and they actually leave a bigger ecological footprint than any gas car does in the end .

Solve those issues and they MIGHT have a chance,,,

but for me ,,give me a bad a** lumpy small block V8 in a car that is pleasing to look at and that handles well and I’ll be all over it .

All you have to do is look at any car lot and you can see there isn’t really a demand for them , case in point , I dropped my Daughter off to pick up her car after being serviced and noticed row after row of 2023, 24, and now 25 model year electrics still sitting on the lot. Not just a few either , more like a hundred or more !

Myself I wouldn’t take one as a gift to be honest unless it was an antique one, then I’d still have to think about it.