How a ’60s slot-car championship propelled three Midwest kids to the big leagues

High-level video-game competitions, including racing sims, have become career opportunities, with the prize pools for major events running into the tens of millions of dollars. Sixty years ago, there weren’t racing simulators, and only major league athletes made a living playing games; but with sponsorship from a major automaker, one toy company gave young people the chance to race to win. The cars may have been tiny and the prizes well below seven figures, but the competition was life changing.

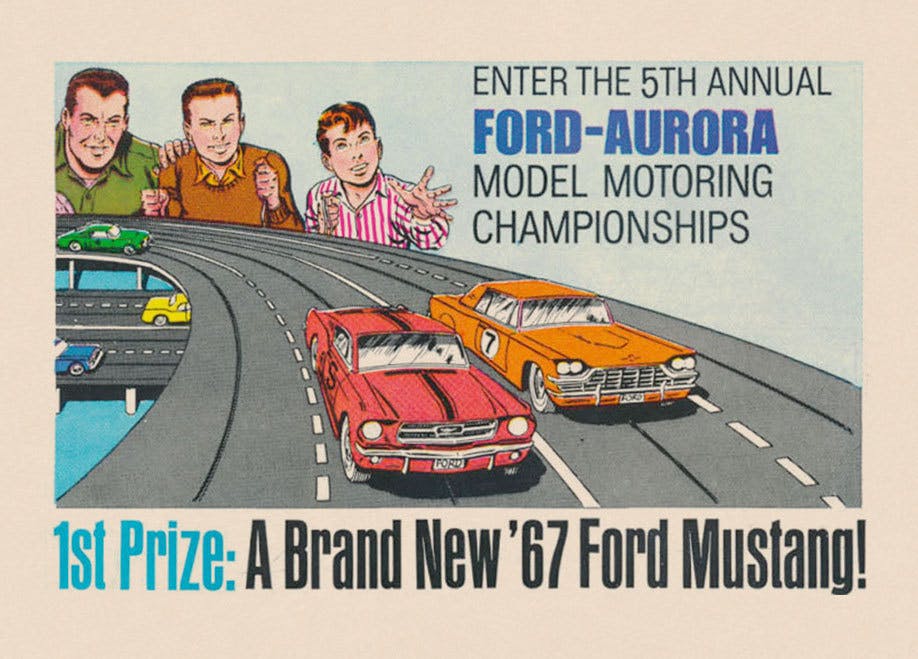

In the early 1960s, it was popular for big companies to sponsor youth competitions, often with college scholarships as prizes. General Motors had the Fisher Body Craftsmen’s Guild, the National Football League started its Punt, Pass, and Kick competition, and in 1961 Ford Motor Company teamed up with model maker Aurora Plastics Corporation to run the Ford-Aurora Model Motoring Championships, which ran for five years, starting in 1962.

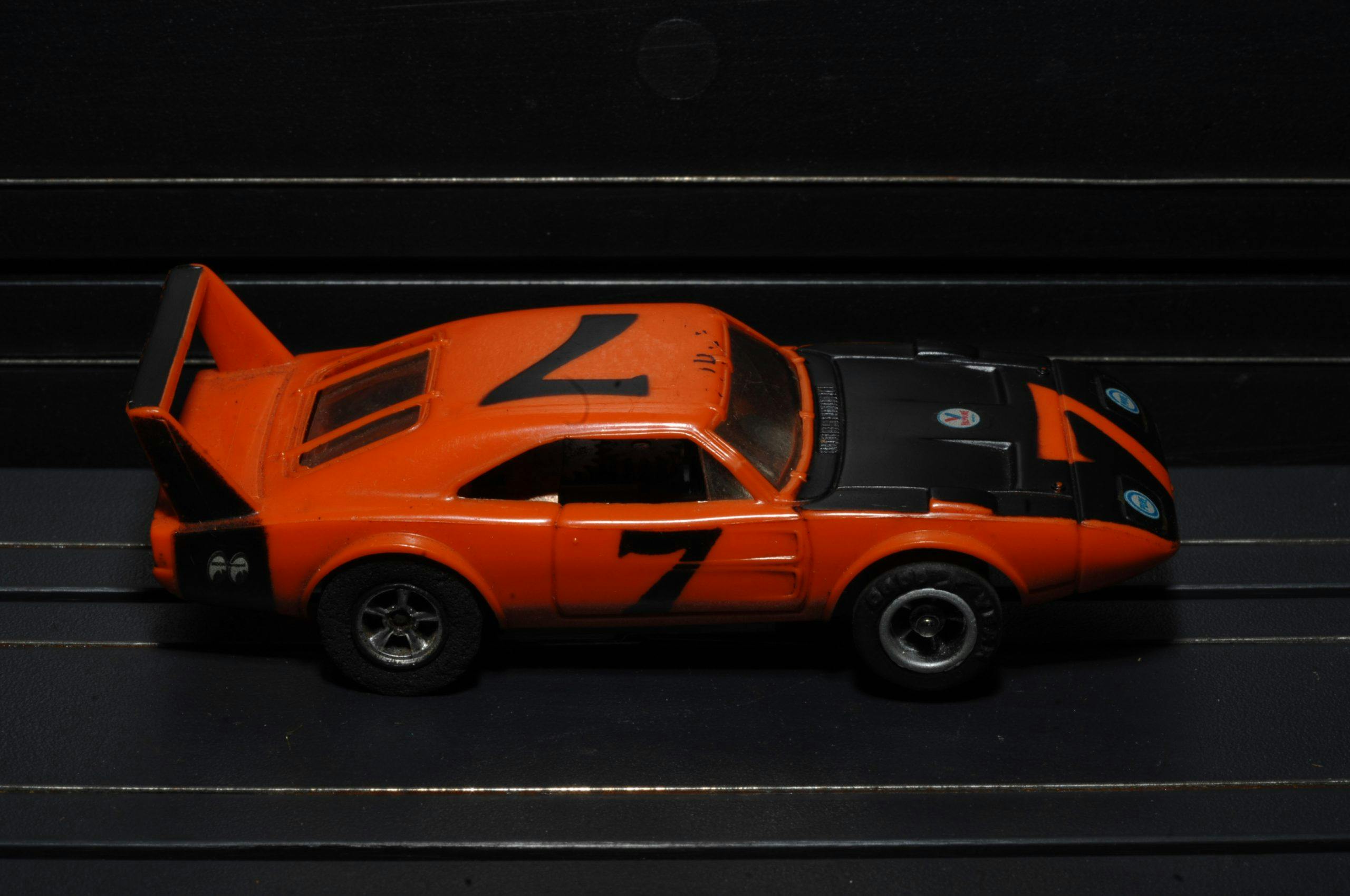

Aurora—based in Hempstead, Long Island—was originally a maker of plastic model kits. By the late 1950s, however, kids wanted more than static models and the slot-car craze was born. In 1957, Scalextric in the U.K. introduced the first modern slot-car sets with 1:30 (later changed to 1:32) scale vehicles. By late 1959, the fad had crossed the Atlantic. U.S.-based Strombecker company was first to the stateside slot-car party with a system that used the bodies from existing 1:24-scale model-car kits.

Thinking that table-top layouts might appeal to parents more than the large-scale tracks, which could take up an entire room, Aurora jumped into the craze, buying the rights to the U.K.-based Playcraft’s Model Motoring HO-gauge racing set and introducing the first Aurora Model Motoring versions in time for Christmas, 1960. HO is technically 1:87 scale, so the cars and tracks are a fraction of the size of the larger scales (modern HO cars may diverge from the measurement). Aurora’s intuition proved accurate, and the company would sell over 25 million HO-scale race cars over the next five years, surpassing the sale figures of Ford and Chevrolet combined.

Someone at Ford apparently noticed, too. Since Aurora already cooperated with the Blue Oval in the production of accurate, licensed models, it was probably not too difficult to set up the racing championships. As with the NFL’s Punt, Pass, and Kick competition, there were local competitions held at popular hobby shops and slot-car raceways. Winners progressed to state, regional, and finally national championships, which were significant enough to merit a live television broadcast.

Though it was a national competition with thousands of participants, a group of three boys in Rapid City, South Dakota—a small city of about 43,000 people in the 1960s—came to dominate the Ford-Aurora Model Motoring competition. One of the trio made the finals in the event’s first year; of the four remaining championships, two belonged to one of these Rapid City contenders. The late, great Mark Donohue was famous for wanting an “unfair advantage” when he strapped himself into one of Roger Penske’s race cars. One might say that the Rapid City boys—Jeff Davis, Ron Colerick, and John Seele—had a similar leg-up on the competition.

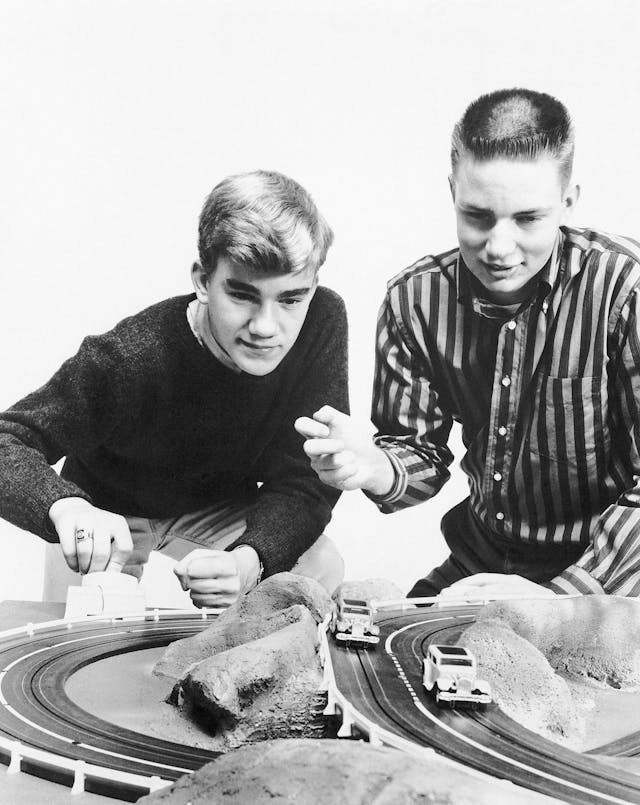

Slot-car raceways proliferated in the 1960s. At its peak, the hobby generated a half billion dollars a year in sales, with as many as 3000 raceways in the United States. Compared to the simple figure-eight tracks most kids used at home, the raceway circuits were more complex, much longer, and much, much faster. The industry and hobbyists consistently developed stronger motors, lighter chassis, and stickier tires. Speeds, naturally, increased.

As the hobby grew, however, slot-car establishments developed a bit of an unsavory reputation among parents. Those shops charged per lap, and often had other coin-operated amusement devices like pinball machines. Both of those things could drain a kid’s piggy bank. Fortunately for the boys of Rapid City, their parents didn’t object to them hanging around a slot-car joint. That’s because Ron Colerick’s father Lloyd owned Toy Hobby Center, the nexus of slot-car in Rapid City.

“We had races every Friday night and all day Saturday,” Colerick told the Rapid City Journal in 2003.

Colerick was coached by Davis, a finalist in the event’s first year, who may have enjoyed even better odds than Colerick. “I spent hours racing at the [Toy Hobby Center] store. I was there so much that Lloyd gave me a job.”

With Davis coaching, Colerick would race for up to five hours a day at his father’s hobby store. When Seeley and Colerick made it to the semifinals in New York City in 1963, they asked Davis to come along as a coach. Colerick narrowly earned a spot in the finals, winning the last semifinal heat by just an 1:87-scale car length, about two inches. With the slowest qualifying time, Colerick also ended up in the worst lane for the finals, and an early spin-out made things even worse; but once he got going, nothing could break his focus.

“I was in kind of a trance. It was good that I had practiced so much that I was able to just race on reflex, Colerick told the Rapid City paper. “My age may have been an advantage,” he continued. “At 12 years old, I might have been numb to the pressure.”

That year’s finals were broadcast live on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, with play-by-play announcing by Stirling Moss. Aurora sold racing sets branded with the racing legend’s name, and Moss awarded a trophy that was almost as big as the young contestant.

Years before he could get his driver’s license or graduate from high school, 12-year-old Colerick won a $2000 college scholarship and a 1963 Thunderbird Sports Roadster (that’s the one with the fairings on the tonneau cover). That car is now owned by Aurora Model Motoring collector and guru Bob Beers. Lest you think $2000 a stingy amount for a college scholarship, consider that it would have covered all but $200 or so in tuition for the average four-year college in 1963—for all four years.

According to Thomas Graham’s book on Aurora slot cars, when Moss handed the young man the keys to his new T-bird, Colerick cheekily said: “Neat, man. I’ll let my Dad drive it sometimes.” The Aurora folks were less pleased with Carson’s ad lib—”You mean he gets a Thunderbird for that?”—since it sounded like a slight on the event’s significance. Perhaps in a dig at Carson, Aurora moved the broadcast for the following year’s championships to the popular I’ve Got A Secret game show, hosted by comedian Steve Allen, The Tonight Show‘s original host. Once again, Stirling Moss was on hand.

Seeley won a 1966 Ford Mustang in the ’65 championships, which was broadcast on the Mike Douglas talk show. He was likely the only 9th-grader in America with his own full-scale Mustang, and it made him a popular guy: “When you’re 14 or 15, and you have a brand-new Ford Mustang, that doesn’t hurt your appeal,” he said. Seeley sold the Mustang while in college, and it’s currently owned by Bob Beers.

Three finalists in five years, all from the same small city in the Midwest. It looks like a statistical anomaly—even a suspicious one—but the secret to the Rapid City boys’ success wasn’t breaking the rules. It was hard work, lots of practice, and some technical mods.

“We didn’t cheat, but we were making adjustments to the cars that the others guys at the national level weren’t even thinking of, ” Davis said. His finals were broadcast live on NBC’s Today Show since, as a major advertiser, Ford had some influence on network programming.

All three of the boys, now senior citizens, have said that the Ford-Aurora Model Motoring Championships were influential events in their lives. Seeley used his scholarship to go to Grinnell College, later earning a MBA from Dartmouth. After eight years with Proctor and Gamble’s marketing department, he started his own marketing, management and consulting firm in Boston. He’s currently the president of The American Consulting Group, an agency with clients at the top tiers of corporate America. “The people I interviewed with at Proctor and Gamble specifically mentioned this one event that signaled that I was someone who could focus and excel and was very competitive early on,” he said.

After serving for 43 years as a judge in Iowa’s 7th judicial circuit, Davis retired in 2019. Davis said that the discipline and commitment he learned from “an intense four or five years” competing in the Ford-Aurora championship was good preparation for law school.

Colerick started North Central Supply and NCS Manufacturing to make and sell doors and other related hardware for commercial buildings, employing dozens of people and passing on the lessons he learned as a young slot car racer.

“I always tell my employees that the competition gets pretty thin after 5:30 p.m. Staying a little longer and working a little harder will eventually pay off,” he said.

If only we could all spend those extra hours at a slot-car track, like this Midwest trio did. Who would have guessed that the same kids who haunted Rapid City’s Toy Hobby Center would make national television—and, decades later, point back to Aurora’s championship as a defining moment in their careers? Their stories prove that, whether full-scale or 1:87, simulated or real, cars have the power to influence and shape lives.

Good story. Just a small correction: commercial raceways charged by time, usually in quarter-hour segments, not by the lap. It was generally $1 to $1.50 an hour, depending on the center and track, and you could get 15 minutes for a quarter. I don’t think that many had unsavory reputations either, but then again, I worked at my local raceway!

Thank you – great article