Lamborghini’s wild ownership history is almost as colorful as its cars

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Now two decades into relatively stable ownership under the auspices of Audi AG, the future of Italy’s most famous bull stable is in question. Early in October 2020, Reuters described a plan drawn up by corporate parent Volkswagen to list at least a substantial portion of Lamborghini’s sports car operations on the global stock market.

The notion of selling Lamborghini was a move perhaps intended to capitalize on the momentum behind the public offering of the brand’s longtime rival Ferrari, which made megabucks when Fiat Chrysler put 10 percent of the company in the hands of new shareholders. As Volkswagen Group nervously eyes the future costs of electrification, cash becomes increasingly important, and Lamborghini’s hydrocarbon-loving fans may not react favorably to a transition to battery packs.

While VW Group ultimately resolved in December to keep Lamborghini (and Ducati) in the fold, raging bull fans with a long memory shouldn’t be surprised by the brand’s recently tenuous position. The years leading up to Audi’s relatively secure ownership were, after all, anything but. The company has attracted a long list of apprentice impresarios who quickly discovered that owning a low-volume, high-priced exotic car company isn’t exactly the simplest ticket to fame and fortune.

Easy sailing early on

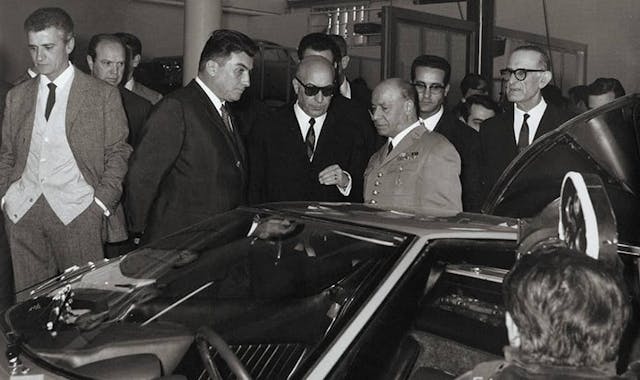

Ferruccio Lamborghini was a man of many interests, and prior to building sports cars he also did a brisk business in tractors. (Lamborghini Trattori was his original piggy bank from which he launched the Automobili branch of his empire.) Alongside his ventures in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning, Lamborghini’s automotive and agricultural enterprises helped make him a titan of industry in post-WWII Italy.

From 1963 until the end of the decade, business went well for Lamborghini Automobili, but a number of deals gone bad on the Trattori side—particularly with dictators in the developing world—began to seriously strain the boss’s finances. Lamborghini dumped many of his holdings in order to stay cash-positive. In the aftermath, Ferruccio sought out a lifeline that both ended his control over the cars that bore his name and kicked off a tumultuous period for his namesake brand.

The Swiss connection

First up on the Lamborghini carousel of deep-pocketed suitors was Georges-Henri Rossetti. Given that Automobili was still making a profit when the deal was struck to sell the Swiss-born businessman a 51 percent interest in 1972, Ferruccio Lamborghini’s continued involvement was more like a partnership than a direct hand-off. Indeed, the former boss continued his unusual habit of pitching in on the factory floor wherever he was needed, ostensibly so that nobody would suspect he was plotting his way out of the entire enterprise.

Rossetti, for his part, had little interest in proximity to Lamborghini’s facility in Sant’Agata, nor did he involve himself much in the day-to-day affairs of the company. He managed his hands-off stewardship of the company from distant Switzerland, as the Countach moved slowly from prototype toward production model.

Rossetti was therefore blindsided by the effect that the 1973 energy crisis had on almost every automotive manufacturer, but particularly on those like Lamborghini that were focused on building tiny numbers of gas-guzzling, high-dollar weekend toys. It was the second such shock in a very short space of time, coming hot on the heels of the original OPEC embargo three years earlier.

At that point, the red ink drowned out the black. Sensing that the end was near, Ferruccio decided it was time to get out while the going was somewhat good. In 1974, the same year that the LP400 Countach went on sale, the once-proud Italian tycoon and his 49 percent interest walked away from his company forever, abandoning the assembly spaces he had once cheerfully haunted. He sold his stake to another Swiss businessman, René Leimer, who had been sweet-talked into the venture by his buddy Rossetti.

Cheetahs and Germans

The era of shenanigans hereby began. Rossetti and Leimer were tasked with keeping Lamborghini Automobili healthy, all during a period when even mighty Ferrari had been auctioned off to Fiat in order to keep the lights on. The LP400 was selling well, but the company’s finances were in such poor shape that it couldn’t afford to purchase the raw materials needed to build customer cars in a timely manner. This led to extremely long waiting lists. In some cases, paid-for rides were sitting pretty on an auto show dais for weeks, if not months, before they ended up in customer hands.

Sensing disaster, the Swiss pair made two fateful rescue attempts that nearly destroyed the company. First came the decision to fund an ultra-niche off-road project, the Chrysler-powered Cheetah, which American company Mobility Technology International (MTI) wanted Lamborghini to build in hopes that it would win a contract from the U.S. military. (AM General got the go-ahead that eventually yielded the Humvee.) In all likelihood, Lamborghini was hoping to turn additional profit by spinning off a civilian version of the Cheetah it could sell to clients in the Middle East.

Second, Rossetti and Leimer accepted a contract that permitted BMW to use Lamborghini assembly facilities—which were idled from lack of parts—to construct the BMW M1 race car. It was a bright enough prospect that Rossetti was able to leverage the deal to uncork a trickle of additional support from the Italian government.

In the short space of just two years, it all came apart. After the Cheetah debuted at the Geneva show in 1977, MTI and Lamborghini got into legal trouble when FMC (Food Machinery Chemical Corporation) alleged the Cheetah was a rip-off of its earlier 1970 prototype for the U.S. military. On top of that, Lamborghini had nowhere near the financial wherewithal required to develop these vehicles, let alone the Cheetah and the M1 at the same. Lamborghini even asked BMW for a loan, which is rarely a good sign.

Out of cash and unable to soak the Italian government one last time, Lamborghini couldn’t resolve the Cheetah prototype’s major problems without the military contracts it had counted on. Simultaneously, BMW pulled the rug out on the M1, unwilling to go out on a limb with Lamborghini any further.

Sugar brothers to the rescue

Dark times in Sant’Agata saw the once-proud Lamborghini brand pass from Swiss hands into the reluctant embrace of the Italian government, following a declaration of bankruptcy in 1978. Rossetti and Leimer did their best to find a new caretaker for what remained of Automobili’s assets, but after a period of arms-length ownership controlled almost entirely by appointees of the Italian judiciary system, and a battle between various investment interests incapable of agreeing how the company should be run, an unlikely pair of heirs to an African sugar empire made a tentative purchase of the company.

The terms of the deal were unusual: Jean-Claude and Patrick Mimran were put on three-year, supervised probation at the head of Automobili, after which they’d be allowed to actually purchase the company. The two brothers were oddballs for car manufacturer owners—they were in their mid-20s, had zero experience in the industry, and were diametrically opposed to the Italian establishment in terms of comportment and personal style.

By the brothers’ working together with more established businessmen and seasoned automotive hands, however, Lambo’s turnaround was swift. Only a few months after brokering the company’s sale in 1980, the Jalpa went on the market to critical acclaim and commercial success. A modernized Countach followed, and even the ghost of the Cheetah was rehabilitated from company-killer to off-road icon with the success of the LM002 program.

At last, some runway

Lamborghini’s growth throughout the Mimrans’ ownership pumped up its value and provided the brothers with a very nice return on their $3 million investment when they sold the company to Chrysler in 1987 for more than eight times that amount.

The six or so years that Automobili spent under the umbrella of its American master were also soaked in cash, with Lee Iacocca splashing money on new vehicle development as well as on various racing and cross-pollination projects that pointed the brand in a variety of new directions. Iacocca, the father of the minivan, even tapped Lambo to build one of their own, dubbed the Bertone Genesis. This V-12-powered monstrosity raised as many questions about the automaker’s control over its own destiny as it raised eyebrows.

It was a whirlwind romance that saw Lamborghini gain its first truly modern dealership network in the United States, along with a fantastic new car—the Diablo—to sell through it. Despite the latter’s initial success, a global recession in the early 1990s cooled the heels of would-be supercar buyers and sent Lamborghini to its next, and most dubious, string-puller.

Mega-sketch

The name “Megatech” suggests a conglomerate comprised of James Bond super-villains or faceless Silicon Valley drones. The truth was even stranger. Having had its fill of exotic stewardship, Chrysler dumped Lambo to Megatech in 1994 for $40M—a sliver of what it had invested.

The company was registered in Bermuda but had roots on a far more distant land. The Megatech banner was a front to disguise the Indonesian origins of its new controller, Tommy Suharto, who was the son of Indonesia’s 30-year president. In partnership with a Malaysian company called Mycom Setdco (jointly owned by a former member of the Malaysian intelligence community who had once been in charge of anti-Communist operations), the younger Suharto did his part in washing millions of dollars of his father’s ill-gotten gains. This deceptive business practice characterized not just his flirtation with Lamborghini but also his ownership and subsequent mismanagement of supercar builder Vector.

Ostensibly, Lamborghini was going to help Indonesia launch its own domestic car industry, a prospect that even the brass in Sant’Agata considered dubious at best. Alongside this brief affair, a planned collaboration between Lamborghini and Vector also collapsed when the latter couldn’t pay for the V-12 engines it had requested. Barely able to break even by 1998, Megatech moved on, pocketing a reported $110M when it sold Lamborghini to Audi like a hot potato.

Calmer seas

No matter what Audi and VW Group end up doing with the company long-term, it seems unlikely that Lamborghini will ever again be subjected to the half-baked business practices it somehow survived in the past. The last 20-plus years of growth under Audi ownership has inflated the value of the brand well past the grasp of any bored, wealthy dilettante looking to dip toes in the seemingly glamorous world of exotic automobiles. After so many years of wandering in the wilderness, the focus these days is firmly on the colorful characters in Lamborghini’s showrooms, not in its boardrooms.