Spindizzies: Nitro-fueled tether cars are collectible American racing history

Tether car racing, also known as spindizzy racing, began in the late 1930s when a bunch of California kids cobbled together home-built model aircraft engine-powered cars running on tires pilfered from Goodyear and Firestone ashtrays. Early tether car bodies were built to look like real-world circle track cars and made of everything from Cracker Jack boxes to hand-formed aluminum.

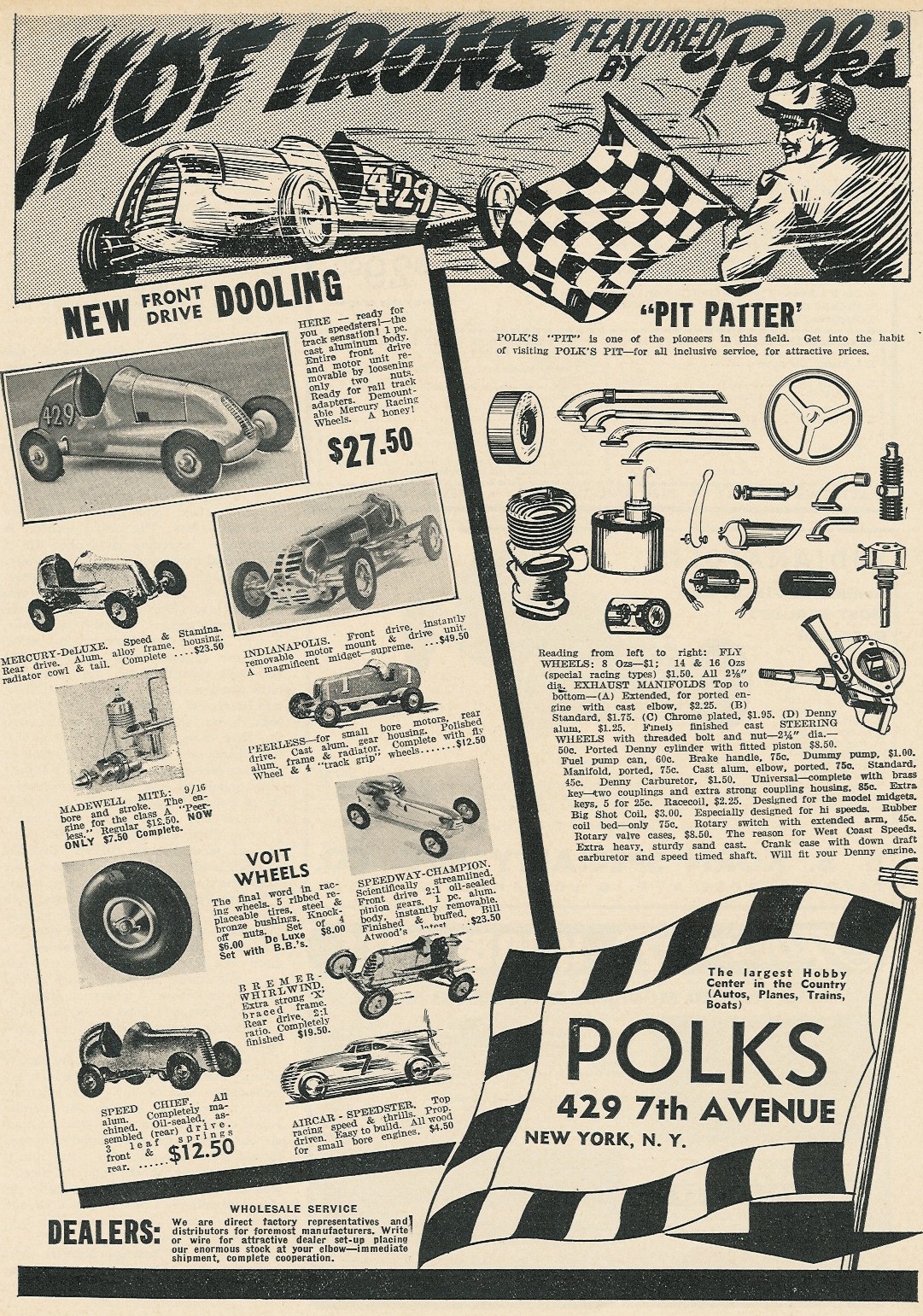

Tether car racing quickly grew in popularity, and soon the racers incorporated craftsmanship and engineering that rivaled their full-size counterparts. Racers experimented with front and rear-wheel drive configurations, just like their Indy and circle track influence. Manufacturers tooled up and met increasing demand with DIY component kits and ready-to-race cars like so many scaled-down Kurtis Krafts.

In the beginning, tether car racers hooked their cars up to a string and stood at the center of a circle passing the lines over each other as one car overtook another. Multi-string chaos gave way to a long steel wire mounted on a ball bearing center pivot. The cars roared around in a perfect circle until they were stopped by a dry fuel tank or hitting the kill switch with a stick. The wire tether setup limited the number of cars that could race simultaneously, so enterprising racers developed banked tracks with railed lanes that allowed six or more cars to race at a time. Tiny sets of steel wheels or bearings kept the spindizzies in their lanes like mini monorails. Multi-lane racing attracted spectators, along with more racers, and popularity snowballed.

Early tether cars ran around 40 mph and quickly surpassed full-size circle track midget speeds. Pre-war cable tethered racers hit 100 mph, and oval track rail jobs went about 70 mph, limited in part by friction between the tiny wheels and the L-shaped rail that kept the cars from flying off the track. Racing ramped up in the late ’30s, slowed down during the war, and fired up in the post-war period. Sanctioning bodies like the AMRCA, MRCA, IMRCA, and WSMRCA made it official with weigh-ins, racing classes, and electronic timing. Large displacement Prototypes, or big cars were at the top of the field, and Streamliners pushed through the air even faster with bodies similar to land speed racers. The big cars and streamliners are among the most collectible tether cars today.

Streamline and big car spindizzy racers took their midget and land speed racing influence full circle in the late ’40s. Tether car pioneers, manufacturers, and racers, the Dooling Brothers, were early proponents of nitromethane fuel. The brothers teamed up with glow-plug inventor Ray Arden and tested his Formula B fuel. The nitromethane, methanol, and castor oil blend worked so well in Dooling engines that the brothers blended and sold their fuel to fellow racers. The Dooling nitro fuel also caught the attention of Los Angeles midget racer and tuner Vic Edlebrock Sr., who asked the brothers where they sourced raw nitromethane, and ordered up two 50-gallon barrels of pure nitro for his midget racing program. The circle was complete. Tether car and midget racers, early hot rodders, dry lakes land speeders, and early drag racers all shared the same Southern California timeline (watch Part 1 and Part 2).

Big cars and streamliners were hand-crafted marvels of miniaturized engineering. Some years ago, in the same general SoCal vicinity where tether car racing began, I ran into a tether car built by the departed cylinder head porter, drag racer, streamliner pioneer, and sculptor Jocko Johnson. Jocko’s Supercharged Cyclone was equipped with a one-of-none fully operational centrifugal supercharger hand-built by Jocko himself. The rest of the Cyclone was fine art, finished to a Bugatti Type 35-level of detail from its hand-shaped aluminum body to jeweled nuts and bolts. The Supercharged Cyclone recently sold at Mecum’s Dick Barbour Tether Car Collection auction for more than $10,000 as a testament to its craftsmanship and significance in American motorsports design and engineering.

Tether car racing was a victim of its own success in the end. Nitromethane and streamlining pushed tether cars to speeds over 150 mph, a racing achievement that ironically may have led to the decline of the sport. At those speeds, the cars were going too fast for spectators to see and top-class racing costs rose beyond what most racers could afford. Ready-to-run cars sold for about $45 in 1940, but by the late 1950s, running a prototype or streamliner could cost $300, or about $2700 in today’s dollars. Smaller-displacement ready-to-run cars like the mass-produced Thimble Drome and Rodzy were far more affordable and hit the market by the thousands as the popularity of sanctioned big car racing waned. Tether car racing endures today with organizations like the American Miniature Racing Car Association (AMRCA), which hosts races nationwide. The electric slot car craze that followed the spindizzies hit its own apex in the ’60s with multi-lane banked tracks and racing series that paralleled the nitro-burning tether car phenomenon.

Drone racing could be considered the contemporary equivalent of the tether car craze, and it’s possible that years from now, people will look at today’s drones and marvel at innovation and craftsmanship as we look at spindizzies now. Whether a battery-electric propeller drone will be collectible in a world of maglev speedsters with fusion reaction drives is uncertain. Still, drone racers might develop breakthrough racing technology of the future.

STILL BUILDING TETHER CARS. I AM 85 YR. OLD , SO IT WILL NOT BE LONG WHEN I OR WIFE WILL WANT TO SELL THEM. NEED INFO. ON AUCTION OF CARS. HAVE 25 OF THEM + ENGINES AND ALL KINDS OF PARTS I WORKED UNDER THE NAME OF ARTWORKS BY BARRY. COLUMBUS OHIO. OH YOU MAY HELP WITH MY PAINTINGS. MY IST SALE WAS IN 1957. I PAINT WHATEVER CUSTOMER WOULD ASK FOR. I AM KNOWN FOR MY PORTRAIT WORK. BARRY REBER

Barry I’m guessing your tether car collection would be worth some very good money. A couple Dooling’s just sold from an auction in Cedarville, Ohio for well over $1,200 +. Don’t give them away. If you can look them up on Ebay for instance to see what they sell for you might be shocked. Good Luck. Ken

I’ve just been collecting for 4 yrs. I am very interested in the tether cars you are considering selling. If you can forward pictures and contact information I will get back wioth you. 352 408 6996

Good auction house, Richmond Auctions, Greenville, S C