The lost 1939 Antarctic Snow Cruiser was outrageous, ambitious, and a colossal failure

Far away in the desolate, crystal freeze of Antarctica, all that remains of Little America lies buried under hundreds of feet of snow. Located south of the Bay of Wales on the Ross Ice Shelf, this utterly remote spot was not host to some ill-fated permanent settlement, but rather to a series of U.S. exploration bases in the 1930s–50s. Those sites are long-since abandoned, of course. But somewhere, perhaps encased in snow and ice or at the bottom of the ocean, lies a 37-ton, 55-foot-long, 12-foot tall industrial behemoth from a famed 1939 American research expedition—the Antarctic Snow Cruiser.

The tale of the Snow Cruiser is one of inspiring industriousness and ingenuity. Nevertheless, there’s an excellent reason this gargantuan ice crawler was a one-off U.S. government project that never made it back from Antarctica, let alone ushered in a generation of exploratory winter vehicles: the Snow Cruiser was a complete bust.

20200312204658)

The Antarctic Snow Cruiser was developed under the direction of famed explorer Admiral Richard Byrd. His second-in-command, Dr. Thomas Poulter, returned from a previous (1934) Antarctic expedition with the idea for a massive, purpose-built transport vehicle for Antarctic exploration. It was envisioned as an unstoppable fortress for long-distance travel on the continent’s endless swaths of snow and ice, especially in punishing weather. Through Poulter’s role as scientific director of Chicago’s Research Foundation of the Armour Institute of Technology, he convinced colleagues there to design the Snow Cruiser, an endeavor that spanned roughly two years between 1937–39. As Admiral Byrd was planning his third Antarctic expedition in the spring of 1939, Poulter and Foundation director Harold Vagtborg successfully pitched the Snow Cruiser’s inclusion in these plans to officials in Washington D.C. overseeing the United States Antarctic Service. The Foundation was responsible for physically constructing the vehicle and coming up with the estimated $150,000 in necessary funding.

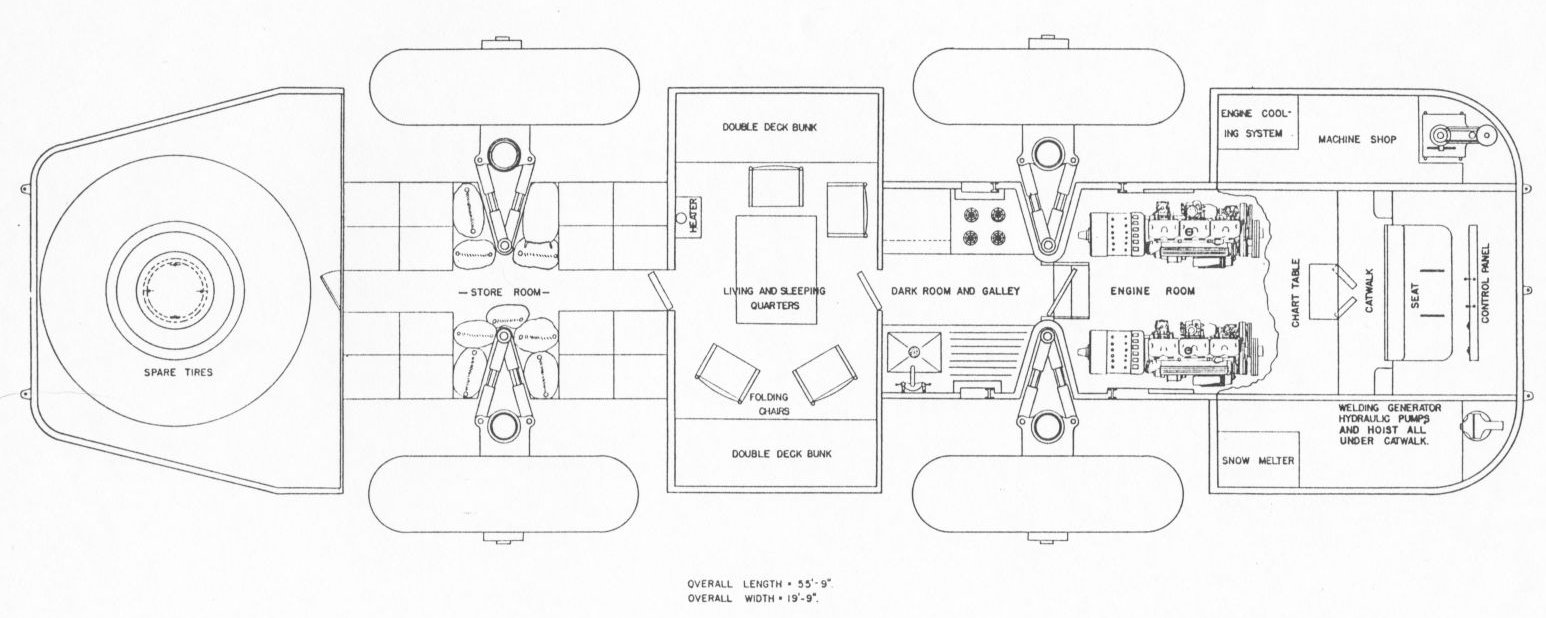

The Foundation began to build the Snow Cruiser on August 8, 1939, a process which took about 11 weeks. Designed particularly for traversing crevasses, the vehicle had long overhangs at either end, as well as retractable wheels to assist in this process. The retracting wheels, which tucked the wheels into housings where they were warmed by engine exhaust gasses, also prevented the smooth, treadless 10-foot Goodyear tires from cracking in the cold. (Yes, we will discuss the rubber more in a bit.) The Cruiser could accommodate a crew of four or five, and the flat upper area between the 20-foot wheelbase was intended to hold a small plane brought along for the purpose of aerial surveys of the terrain. Up front, in an elevated control room, sat the Snow Cruiser driver and charter. Underneath the control room, beneath a catwalk, were the machine shop, snow melter, and a variety of generators, pumps, and hoists. Just ahead of the front wheels was the engine room, housing a pair of Cummins inline-six diesel engines that combined for 300 horsepower. The engines were paired with two generators and four electric motors, courtesy of General Electric, which also combined for 300 hp. Behind the front wheels were the photo dark room and gallery, followed by the crew’s living and sleeping quarters. At the rear wheels you’d find the store room; way in the back was the storage compartment for two spare tires.

The design was hailed as a remarkable achievement of American engineering. There was, however, a bit of an obstacle before the Snow Cruiser could begin its grand exploration of Antarctica. The Foundation’s production facility at the Pullman Company near Chicago was 1020 miles away from Boston, where the United States Coast Guard Cutter North Star was docked and awaiting its arrival. The sensible solution to this pickle was to drive the beast, with its top speed of 30 mph, the whole way to Beantown.

Maybe Admiral Byrd’s team should have heeded the warnings of this shakedown trip, which included a huge police escort and was beset with problems. The Snow Cruiser got hit by a truck in Indiana and later suffered fuel pump trouble. Six miles outside of Lima, Ohio, it hit the corner of a bridge and fell into a small creek, where it remained for three days. If it couldn’t handle the treacherous, unforgiving landscape of middle America, how was the Snow Cruiser ever going to handle, say, Antarctica? These were appropriate questions to ask, but meanwhile, excited by a press blitz that included an October 1939 cover story in Popular Mechanics, an estimated 125,000 people came out to see the vehicle trundle like a half-tranquilized bear along its journey. Many were enamored of its majesty—and yet increasingly suspect of its supposed capabilities.

Alas, on November 12, 1939, the Snow Cruiser successfully made it to Boston before the North Star’s scheduled departure. The voyage to Antarctica was successful, and on January 15 the ship, anchored at the Bay of Wales, prepared to unload the Snow Cruiser onto the Antarctic shore at the Little America III base. The crew built a big ramp of timber to facilitate the vehicle’s disembarkation, but halfway down the ramp, the wood shattered. Somehow, as the Cruiser feebly tottered toward land, it managed to keep from sinking into icy waters. Poulter gave it full throttle, and the big machine made it to safety.

That was the Snow Cruiser’s final moment of triumph. Before it got far, the vehicle’s huge, smooth rubber tires helplessly spun as the vehicle sank several feet into the snow. Out came the spare tires for additional traction on the front axle, and the crew threw on chains for the rear wheels. Still, the Cruiser couldn’t surmount even snowy hills, likely due to its too-high gear ratios and treadless rubber. It did turn out that driving the Snow Cruiser in reverse was a lot easier, and the crew even managed one journey traveling 92 miles backward. (True, reversing into a Ford was unlikely, but driving rump first into an ice canyon would also have been unfortunate.) Just 15 days later, on January 27, Poulter sailed off from Little America for Big America, leaving a smaller crew in charge of experiments that included seismology and cosmic ray measurements, as well as ice-core sampling.

Even though the Snow Cruiser was essentially a total failure, from the utter lack of traction to the underpowered engines, the vehicle proved to be a solid base of operations and full-time living quarters. Engine coolant traveled through the cabin’s structure, effectively heating the Snow Cruiser’s interior despite the brutally frigid conditions during which air temperatures were around -50 degrees Fahrenheit. Poulter wanted to return to Antarctica and outfit the vehicle with improved parts, but when the U.S. became entangled in World War II, the government focused its funding on the war effort. The Antarctic Snow Cruiser was abandoned at the Little America III base on December 22, 1940.

20200312204816)

Amidst the fascination with post-war technology and innovation, the Snow Cruiser was never again seriously considered a viable project. Other expeditions did locate it in 1946 (determining all it really needed was air in the tires) and again in 1958; in the latter instance, only a bamboo pole marking its location was visible, and the vehicle had to be excavated from many feet of snow with a bulldozer. Inside, it was perfectly preserved, down to the various papers, magazines, and cigarettes scattered about. That was the last time the Snow Cruiser was seen, although some conspiracy theories exist suggesting it was at some point rediscovered and captured by the Soviets during the Cold War. What’s for certain, however, is that a large portion of the Ross Ice Shelf right in Little America’s vicinity fell into the Southern Ocean in the mid-1960s.

(Does all this sound vaguely familiar? Fans of adventure novelist Clive Cussler may recognize the vehicle, since he used it in his book Atlantis Found.)

Today, the Antarctic Snow Cruiser’s fate remains unknown. Like the proverbial mosquito in the amber, it could just as well be preserved under enumerable layers of snow and ice as it could be slumbering deep beneath the waves. Either way, the project was a terrific attempt at greatness, motivated by the ineffable human will to explore and discover.

For more information on the Antarctic Snow Cruiser, visit these sources:

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2016/01/the-antarctic-snow-cruiser-updated/424851/

http://www.joeld.net/snowcruiser/snowcruiser.html

Photos courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

20200312204647)

20200312204653)

20200312204704)

20200312204710)

20200312204822)

20200312204830)

20200312204843)

20200312204851)

20200312204900)

20200312204911)

20200312204923)

20200312204931)

20200312204939)

20200312204951)

20200312205001)

A very interesting and flawed project. Not sure why they didn’t change gearing or the tires.

It’s hard to understand how they thought smooth tires would provide adequate traction on ice and snow.

Yeah that’s agreed. And I think Clive Cussler noticed that little detail, too, because in Atlantis Found, some of the characters had carved treads into the tires.