Mauri Rose: The unsung hero of the Corvette’s racing legacy

Zora Duntov has often been called the father of the Corvette, which is a point that some automobile historians would debate. Only after he saw the Corvette show car at the 1953 General Motors Motorama was Duntov convinced to seek employment at GM, where he was soon named chief engineer for the project. However, if Duntov is going to be assigned presumptive paternity for America’s sports car, Mauri Rose deserves to be considered the Corvette’s godfather.

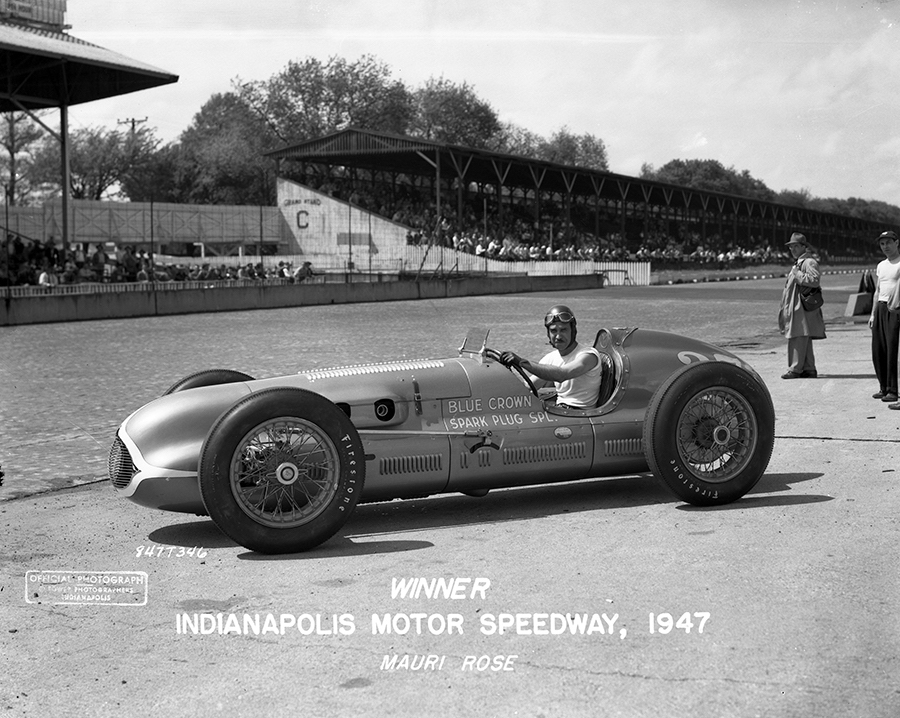

Though he is much better known as a three-time winner of the Indy 500, Rose had critical roles in both creating the first production Corvette and developing the car into a successful racer. Born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1906, Rose started his racing career board tracks in 1927 and moved up in the racing world to starting at Indianapolis Motor Speedway when he was 26. He would eventually compete 15 times at Indy, and in just his third start he came in second by only 27 minutes—then one of the closest finishes ever.

A dapper man with a trimmed mustache, Rose smoked an omnipresent pipe when he wasn’t behind the wheel of a race car. He became an Indy specialist, settling down in Indianapolis and hiring on at the GM subsidiary Allison Engineering. Apparently, he preferred the settled life of an engineer who raced part-time to the nomadic life of a full-time racer. Each spring, when May would rolled around, he’d use his lunch breaks to test and qualify at the Speedway and return to work in the afternoon.

Rose won his first 500 in 1941, the last race before the United States entered World War II. A steering failure put him out of the first postwar race in 1946, but he won the following two years and only retired after a rollover accident in 1951.

20200120165111)

20200120165158)

Rose was not averse to publicity. He played himself in Clark Gable’s 1950 racing flick To Please A Lady, which was staged, in part, at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. While shooting the race, the production company managed to capture a pit fire that engulfed Rose’s car as it was being refueled. Rose calmly got out, waited for his crew to put out the fire, got back in, and drove off to a third place finish. (The movie used footage of the actual race for the film; check out 2:28 in this clip for the pit fire incident.)

Still, he seems to have been a modest man. According to one story (that may be apocryphal), Rose was back on the job the day after one of his Memorial Day victories, casually discussing the race with his coworkers—who had no idea the race winner was in their midst.

While his coworkers at Allison may not have known about Rose’s racing feats, GM engineer Ed Cole certainly did. Cole was responsible for Cadillac’s high-compression overhead-valve V-8, introduced in 1949, and by 1952 he was Chevrolet’s chief engineer. (He would go on to head the team that designed Chevy’s small-block V-8). In the early ’50s, however, Cole was orchestrating the transformation of Harley Earl’s Corvette show car into an actual sports car. That project was assigned the name “Opel,” disguising its intentions as something intended for the European market. Cole had British suspension expert Maurice Olley design the chassis. Olley was joined by Duntov, who by then had arrived at GM, and afterwards by Harry Barr, Russ Sanders, Maurice Rosenberger—and Mauri Rose, who was responsible for fabrication.

After just 10 days, Olley handed Rose an 8.5 by 11-inch sketch of something very close to the production Corvette chassis. Working in a secret loft, away from prying eyes and union work rules, Rose roughed out the design in wood and foam. Once designs were finalized they were transferred to metal in the fabrication shop. While the first generation Corvette is considered to be more of a boulevard cruiser than an actual sports car, its chassis shared little with other production Chevys, and Rose did what he could to give Chevrolet’s 115-hp Blue Flame Six some pep. (That motor, newly revised for 1953, was a revision of a truck engine first introduced in 1941, itself a variant of the original 1924 “Stovebolt Six.”)

20200110155122)

Rose increased the compression and developed a new roller-bearing camshaft with more aggressive timing and increased lift—at the time, the highest valve lift of any American engine. To reduce valve float, each valve got dual springs, and exhaust valves were made of SilChrome alloy steel for durability. The low hood prevented the use of downdraft carbs so three sidedraft Carter units were mounted to a bespoke aluminum intake manifold. Cole wanted a distinctive, sporty exhaust tone, so he specified dual exhausts.

Rose ended up with a 190-hp engine, but the motor was difficult to start and had a rough idle. The team decided to scrap the roller cam and detune the engine to 150 hp (which was still a 30-percent improvement over the stock Blue Flame Six). While the choice of the two-speed Powerglide transmission for the first Corvette has long been criticized, there were production and engineering justifications. In any case, Rose did have the Corvette’s Powerglide reinforced to handle the extra power and torque.

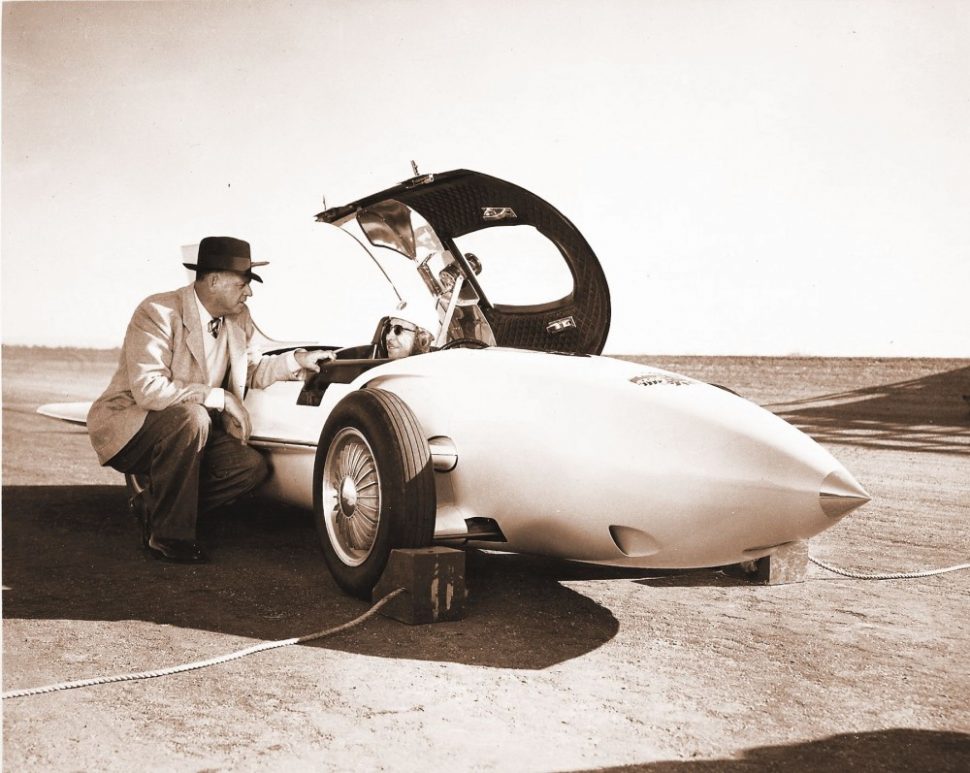

Rose did much of the development test driving as well. Zora Duntov liked to drive fast and he did hit 163 mph in an experimental Corvette at GM’s Arizona Proving grounds; but in Rose’s expert opinion, Duntov was a very good engineer who “couldn’t drive a nail.” The two men were good friends, however, and respected each other’s talents. In fact, in late 1953, it was Duntov who suggested offering racing parts through GM’s regular production option (RPO) system. In 1955, Cole approved that suggestion and put Rose and Duntov in charge. Duntov would do the engineering in Detroit and Rose would do the testing and tuning, working with Smokey Yunick at the latter’s “best damn garage” in Daytona. Rose was also responsible for installing the first V-8 ever to power a Corvette, the experimental EX-87 “Duntov Mule.”

Cole also had Rose and Yunick race-prep two production 1956 Corvettes and refit the Duntov Mule with a ’56 body: first, for some publicity-generating record runs on the beach at Daytona and afterwards, to take on the 12 Hours of Sebring. At the time, Rose and Yunick were also working on Chevy’s NASCAR program.

It may come as a surprise to some, but Zora Duntov originally didn’t see the production Corvette as a race car, so Cole hired John Fitch to manage the team. Though Duntov soon realized he didn’t want to be out of the limelight and joined the project, it was Rose who did the yeoman’s work in turning the boulevard cruiser into a competitive race car.

In early 1957, Rose issued an extensive memo detailing the Corvette’s shortcomings as a racer and specifying the parts it needed to be competitive, researching everything from a new vibration damper on the front of the engine to torque rods to control the rear axle. Working with Chevy engineers, Rose and Yunick designed, tested, and verified the new performance parts and then cataloged them in the RPO system. This logging system meant that Corvettes equipped with these performance-spec parts could still compete as production vehicles.

When the first race-prepped ’Vettes hit the track, they met with resounding success. One of the ’56 Corvettes prepped by Rose and Yunick came in ninth overall and first in class at Sebring in 1957, the Corvette’s first-ever victory as a factory racer. By 1960, the Corvette was the SCCA B Production class champion, and that same year Briggs Cunningham brought home the Corvette’s first trophy from Le Mans.

The Corvette’s early racing success, and the publicity that it generated, played a potentially significant role in convincing GM executives to keep the sports car in production, despite poor sales in the early years. What’s certain is that, in coming years, the legacy of production ’Vettes is intertwined with the prowess of their track-going brethren. Obviously he didn’t do it all by himself, but Mauri Rose was a major factor in creating the foundation for decades of Corvette racing success, and he can rightly share credit for that success in keeping the model alive.

Despite his masterful performances at Indy, and his important role in the development of both the first production and first factory racing Corvettes, Rose didn’t put those achievements at the top of his admittedly impressive resume. The father of two children who were disabled by polio, Rose designed and developed hand controls to make it possible for people without full use of their legs to operate road cars. Rose considered that to be his most significant accomplishment.

While at GM, Rose was also responsible for test driving the experimental turbine-powered Firebird show cars and also appeared in GM advertising. In 1967, when the then-new Camaro was chosen to be the pace car for the Indy 500, Zora Duntov made sure that his friend Mauri was at the wheel. Rose’s last automotive job was working at American Motors. He died on New Year’s Day, 1981, at the age of 74.

The new mid-engine, eighth-generation Corvette was codenamed Zora during development; Duntov was additionally honored with hidden “Easter eggs” on prototypes’ camouflage. Duntov’s dream has finally hit the streets, and the racing legacy that Rose helped build has found its latest form in the wild C8.R revealed late this summer. When the newest pair of Corvette racers makes its competition debut in a few short weeks at the 24 Hours of Daytona, it would be appropriate for Corvette Racing’s “Jake” skull mascot to be joined by another silhouette—a mustachioed gentleman with a pipe.

20200120165130)

20200120165238)

20200120165221)

It’s always interesting to me to find out the history of things, and this article on the beginnings of the Corvette is especially so. The history of the people who pioneered the concept, and pushed the concept forward, in spite of difficulty gives advice to others in similar situations. I’m impressed by Mr. Rose’s humility in considering that his greatest contribution was to enable drivers with disabilities the devices that enabled them to enjoy the freedom and joy of driving. I’m still looking for the driver in that photo of the ’56 Corvette SR, 3/4 view supposedly in motion, finishing out that beautiful green S turn.

A good story. I agree with Robert J. The story of the people who create automobiles is truly interesting.

Over the years I’ve never read about Mr. Mauri Rose in Corvette articles. Great to see the relationship of all the people who work together to make things happen.