Keeping time in the obscure world of the steering wheel clock

As knick-knacks and oddities go, gadgets associated with the automobile make a strong showing. In the 1930s, you could get a bumper-mounted pressure cooker that ran off exhaust gas. Who could forget Chrysler’s Highway Hi-Fi, a 1950s under-dash record player? And how ’bout Chevy’s 12-volt Remington Auto-Home Roll electric razor? Shave while you drive!

The car clock seems downright practical by comparison. But even this ubiquitous little gizmo has veered in interesting directions in the years since the earliest drivers first began hanging pocket watches in leather holders from the dash. Enter the steering wheel clock.

Traditionally, gauges relevant to the driving experience and function of the car were located front and center, while the clock occupied a more central spot farther across the dash, its placement easily accessible to all passengers. Initially, these featured manually wound “8-day” mechanical movements actuated by turning the bezel. Users could wind them up on, say, Sunday before heading off to church, and not have to worry about them until the following Sunday.

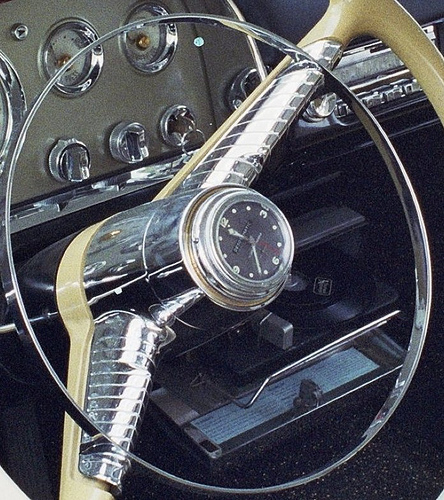

Steering wheel clocks, on the other hand, were aftermarket accessories fitted to—you guessed it—the steering wheel hub. Unlike hand-wind movements, they featured automatic movements, also with an eight-day power reserve, which utilized a rotor that spun with the motion of the wheel to wind the mechanism.

In 1951, Oldsmobile was the first to offer them. They were made by MAAR, a Swiss manufacturer, and required their own special steering wheel. “Special wheel, special turn signal arm, special horn ring,” says Lee Exline, a 55-year-old Iowa resident who has been collecting these rarities for nearly 30 years. His website, www.roadkillontheweb.com, is dedicated to their fascinating history. The package also included a compass that fit into the space in the dash where the old clock had been. Because who needs two clocks?

“The MAAR movement was interesting because it was gyroscopic,” Exline says. “So it worked with acceleration and braking, not just the turning of the steering wheel. You could also rotate the crystal on the face of it to hand-wind the mechanism.”

Chrysler featured its own steering wheel clocks from 1954 to ’58, though ’53 models could be retrofitted. They were available across all the brands and included the Moparmatic, the Chryslermatic, the Plymouthmatic, the Dodgematic, and the DeSotomatic, each featuring a 15-jewel “DK14” Gazda movement in clocks made by another Swiss company, Benrus. They were either factory- or dealer-installed options, and, at $49.95, they weren’t cheap, especially compared to the $12–$15 an optional dash clock cost.

A red pointer on the crystal could be rotated to a specific place to measure elapsed driving time. For marginal nighttime visibility, hands and dial markings were painted with radium. According to Exline, because Dodge changed its horn ring design in 1955, the clock option was 1953–54 only, which makes the Dodgematic-branded clocks the rarest of these rare oddities.

Unlike the MAAR, the Benrus units fit easily into existing steering wheels. Installation was as simple as removing the center ornament with a quarter turn and then putting the clock in its place.

A second-generation “FA14” movement was introduced in 1957, which featured seven jewels and differed functionally in the way you set the time. Rather than twisting the outside of the crystal as in years past, a central push/twist button served the function. Gone was the red pointer for telling elapsed time.

Exline says that Benrus even developed display-back versions for salesmen. “They were never intended to be put in a car. They would sit on the salesman’s desk, and he could flip it over, and you could see through the clear glass backing the pendulum that operated everything.”

By the end of the decade, steering wheel clocks were long gone, though not before MAAR movements also found their way into some Chevrolets, Nashes, and even Volkswagens. Their relegation to the annals of history is due in no small part to electricity and its convenient application to both timepieces and the tiny light that made them visible at night. Which is handy.

Exline’s collection at present stands at about 10, but he’s been buying and selling steering wheel clocks for long enough to know how to find them. “I’ve pulled them out of dealerships. I’ve found ’em at swap meets and in antique shops, where owners don’t know what the hell they are. And, of course, eBay.” His website, too, literally the lone beacon of steering wheel clock light in the vast recesses of the internet, steers them in his direction.

“When people go online to look them up after they’ve cleaned out their dead Aunt Edna’s closet, who do you think they find?” he says. “The only guy on the damn internet who says anything about the damn things.”