The hybrid cars we love to hate deserve a little respect

Granted, all of those self-righteous Toyota Prius drivers cluttering the passing lanes by driving five mph below the speed limit aren’t helping stave off the disdain many enthusiasts have for hybrids. But you’ve gotta give this approach to better gas mileage credit for persistence. Fact is, hybrids were conceived in the horseless carriage days, and they’ll surely be with us until the last barrel of petroleum is consumed.

Modern tech with distant roots

Hybrids got their start at the end of the 19th century, not to save fuel but rather to muster the power needed to get moving. The first recorded example is an 1894 electric bicycle designed Felix Carli, an Italian Count. To double his power supply, Carli supplemented his motor with a box of tensioned rubber bands.

Three years later, Justus Entz, chief engineer at a Philadelphia battery company, added a combustion engine to improve the performance of his electric carriage. This effort went up in smoke (literally) when an errant spark lit the gas tank.

Two hybrids showed up at the 1899 Paris Salon. A Belgian design had a gasoline engine with its flywheel replaced by an electric motor, and a French effort used an engine to power a generator, which sent juice to a pair of electric motors driving the wheels.

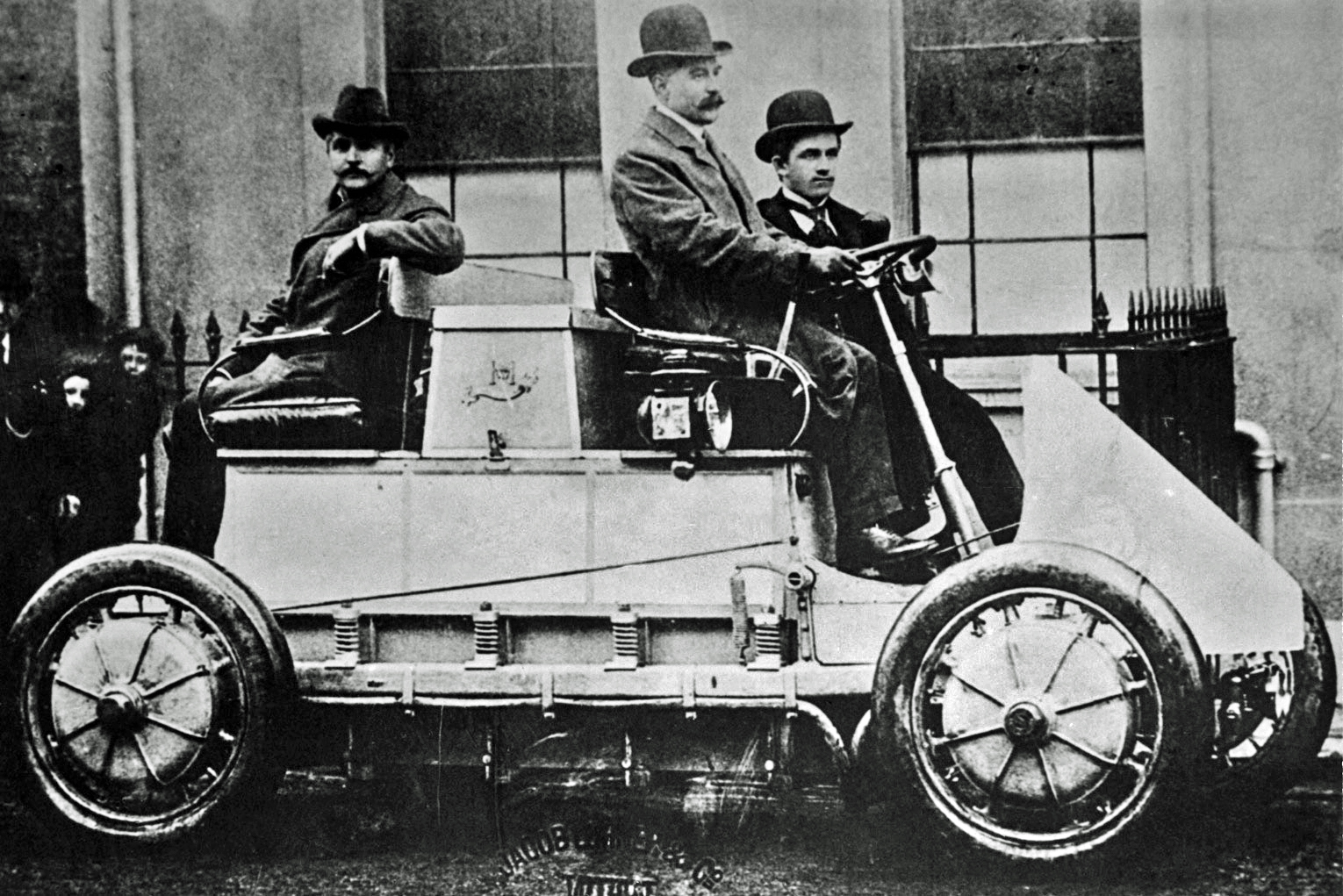

The following year, Ferdinand Porsche (yes, that Ferdinand Porsche) designed a carriage

while working for Austria’s leading vehicle manufacturer, Jacob Lohner, that introduced two brilliant advancements: front-wheel drive and an electric motor built into each front wheel. A combustion engine powered a generator, which in turn energized the motors. A four-wheel drive version with a two-ton battery, two generators, and a 3.5-horsepower Daimler engine entered low-volume production for military, fire-fighting, and Mercedes automobile use.

Two of the most successful U.S. electric vehicle manufacturers—Baker of Cleveland and Woods of Chicago—both introduced hybrids for sale in 1916. They failed to succeed because they cost as much as Cadillac V-8 models that offered electric starting and twice the horsepower.

In 1938, steam-powered trains commenced their trip into the history books when GM’s Electro-Motive Corporation launched diesel-electric locomotives. One huge engine powered a generator wired to the propulsion motors. There was no onboard battery to store energy.

A 1942 engineering book titled Torque Converters or Transmissions for Use with Combustion Engines in Road and Rail Vehicles, by P.M. Heldt, quickly became the hybrid vehicle designer’s bible.

Following passage of the 1970 Clean Air Act, four TRW engineers under contract to the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (precursor to the Environmental Protection Agency), invented an electromechanical transmission capable of blending combustion and electric power sources for propulsion. Years later, Toyota engineers would discover and implement this system for Prius hybrid use.

Two energy crises in the 1970s forced engineers to improve gas mileage with added vigor. Even Briggs & Stratton joined the movement with a six-wheel compact offering 26-horsepower, multi-mode operation, and a 75-mph top speed. Audi’s Duo experimental vehicle had a combustion engine to power the front wheels and an electric more driving the rears.

To address Detroit’s difficulty competing with the Japanese, the Clinton-Gore administration launched a Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles (PNGV) in 1993. In exchange for a hiatus in new federal safety and emissions regulations, the domestic car builders tapped the expertise available at universities, national laboratories, suppliers, and federal agencies to build 80 mpg concept vehicles feasible for mass production. The most ambitious running prototype that emerged was GM’s diesel-hybrid Precept sedan capable of 90 mpg.

Seed for the Prius

Since Toyota had partnered with GM to build cars in California starting in 1984, Japan’s mega maker was peeved to be excluded from the PNGV consortium. Chairman Eiji Toyoda promptly assigned chief engineer Takeshi Uchiyamada to an ambitious project called G21—an advanced global car for the 21st century.

In 1994, Toyota’s new engineering vice president doubled G21’s 50-percent efficiency-improvement goal and ordered that a concept car had to be ready for presentation at the following year’s Tokyo Motor Show.

Uchiyamada-san asked 80 research engineers working under him to propose how this goal could be met. The 30 best ideas were winnowed down to 10, then three, then a single concept. What became the Toyota Hybrid System combined one engine, two electric motor-generators, and a planetary gear set to drive the wheels. Searching the available literature, Toyota engineers had stumbled across TRW’s invention which was rooted in Heldt’s 1942 textbook.

The first Prius prototype ran late in 1995, just after the Tokyo show. Toyota’s top management again pressed the accelerator, ordering cars to market before the Kyoto Protocol climate change conference scheduled for December 1997. Audi’s A4 Avant Duo reached European customers about the same time with a 90-hp turbo-diesel and a 29-hp electric motor teamed up to drive the front wheels.

Hybrids hit the market

The hybrid movement finally reached American buyers at the 1999 North American International (Detroit) Auto Show, when Honda presented a two-seat aluminum-bodied concept called VV. A three-cylinder engine bolted to an electric motor drove the front wheels. By the time the vehicle reached dealers later in the year, the name had been changed to Honda Insight and the window sticker touted remarkable EPA mileage ratings: 61 mpg in city driving and 70 mpg on the highway, which would turn out to be an all-time efficiency record. (Adjusted to conform with current test procedures, the Insight’s EPA ratings are 49 city, 61 highway, and 53 combined mpg.)

Toyota followed a few months later with a second-generation Prius engineered for U.S. buyers with more power, better acceleration, and lower emissions than the Japanese original. Don Esmond, Toyota’s senior vice president in the U.S., dubbed that launch “one of the biggest crap shoots I’ve ever been involved in.” GM magnanimously granted permission to use the word Synergy, which previously described a GM-Toyota research liaison, in Toyota’s resulting Hybrid Synergy Drive nameplate.

In 2003, when the third-generation Prius earned several press awards, Toyota’s U.S. sales president Jim Press called it “the hottest car we’ve ever had.”

Hybrids readily trump the most efficient gas and diesel cars and trucks because of their ability to recover energy that’s normally squandered to aerodynamic drag or braking heat during deceleration. By switching their propulsion motors temporarily to generating mode—what’s colloquially called regen—hybrids capture this energy and convert it to electricity stored in an onboard battery for later use.

Plug it in

While the Toyota Prius has long reigned as America’s favorite hybrid car line, the arrival of the 2011 Chevrolet Volt nudged it off the top of the efficiency heap. Because the Volt can be plugged into an AC power source for battery charging instead of relying wholly on the engine and regen for battery juice, it offers customers the desirable combination of longer electric-only driving with no range anxiety because the engine takes over when the battery is depleted.

Hybrid popularity is directly related to the price of fuel at the pumps. Sales peaked in 2013 at nearly half a million cars offered by scores of makers claiming a 3.2-percent share of the total market. Add to that a 0.3-percent share for more expensive plug-in hybrids.

Hybrid technology revolutionized premier motorsports starting with the Audi R18 e-tron Quattro LenMans endurance racer in 2013 and the entire Formula 1 grid in 2014. Engineering trickle down soon lobbed that technology back to the street in the form of an emerging class of hypercars—Ferrari’s LaFerrari, Koenigsegg’s Regera, McLaren’s P1, Mercedes-AMG’s Project One, and Porsche’s 918 Spyder.

So, while car enthusiasts generally scorn Toyota Priuses and their ilk, hybrids deserve recognition for advancing propulsion technology a major step up the efficiency scale.