Paulie Teutul of American Choppers Charts a New Course

This story first appeared in the November/December 2024 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Join the club to receive our award-winning magazine and enjoy insider access to automotive events, discounts, roadside assistance, and more.

Paul Teutul Jr. grew up on TV. He wasn’t a child actor, but by his own admission, he had a lot of maturing to do when, in his 20s, he was bickering with his dad, Paul Sr., and other cast members of American Chopper. From 2003 to 2012, the popular show and its permutations featured Paul Jr., or “Paulie,” as a brash character and almost a caricature. The show’s central theme—building custom and increasingly ornate motorcycles with compressed time pressure—led to a lot of shouting and tension, much of it spilling into real life. Paul Jr. and Sr. wound up entangled in lawsuits and took years to interact with each other with even a modicum of civility.

Although it’s been a long time since father and son bent metal together, Paulie certainly inherited his dad’s eye. It all started when he was just a kid, honing his welding and fabrication skills in the senior Teutul’s metal shop in Montgomery, New York, in the Hudson Valley. By the time he was becoming a television star and pop icon, Paulie knew bikes and he knew welding, and he was great at using the latter to restore the former, as anyone who routinely channel surfed in the aughts can attest.

Today, you might find Paul Jr. wearing a straw hat as a motorcycle judge at a concours d’elegance, at events like The Amelia and Greenwich. This turn in life, like collecting cars, is new, and he’s slowly getting seasoned. He has restored more vehicles than almost anyone he’ll rub elbows with on the concours circuit but insists that when he walks into the judging room, he expects to be considered “just a face,” despite his TV fame. If some of the stuffier traditionalists in the judging corps initially perceive him as more greasy blue collar than blue blood, it doesn’t faze him. “Their concours world essentially is my world—they just don’t think that at first.”

Truth is, Teutul knows the big-bucks collectors you’ll see at any concours or upscale auction, because he’s parlayed his Paulie television persona into tremendous business success. Today he routinely creates custom, one-of-a-kind bikes as living, corporate totems for clients like Microsoft, Major League Baseball, and Mercedes-Benz. He doesn’t work with a budget or even a design remit—ever.

“There are no drawings, we just listen to them,” he explains. “I’m talking about Cadillac, Geico. All these companies that would normally have levels of approval for the simplest things. They just give me their IP, their colors. You’ve got the chief designer saying, ‘Oh, we just want to see what you come up with.’” Teutul emphasizes that it took nearly two decades of grinding to build that kind of trust, as both a designer and the face of a brand.

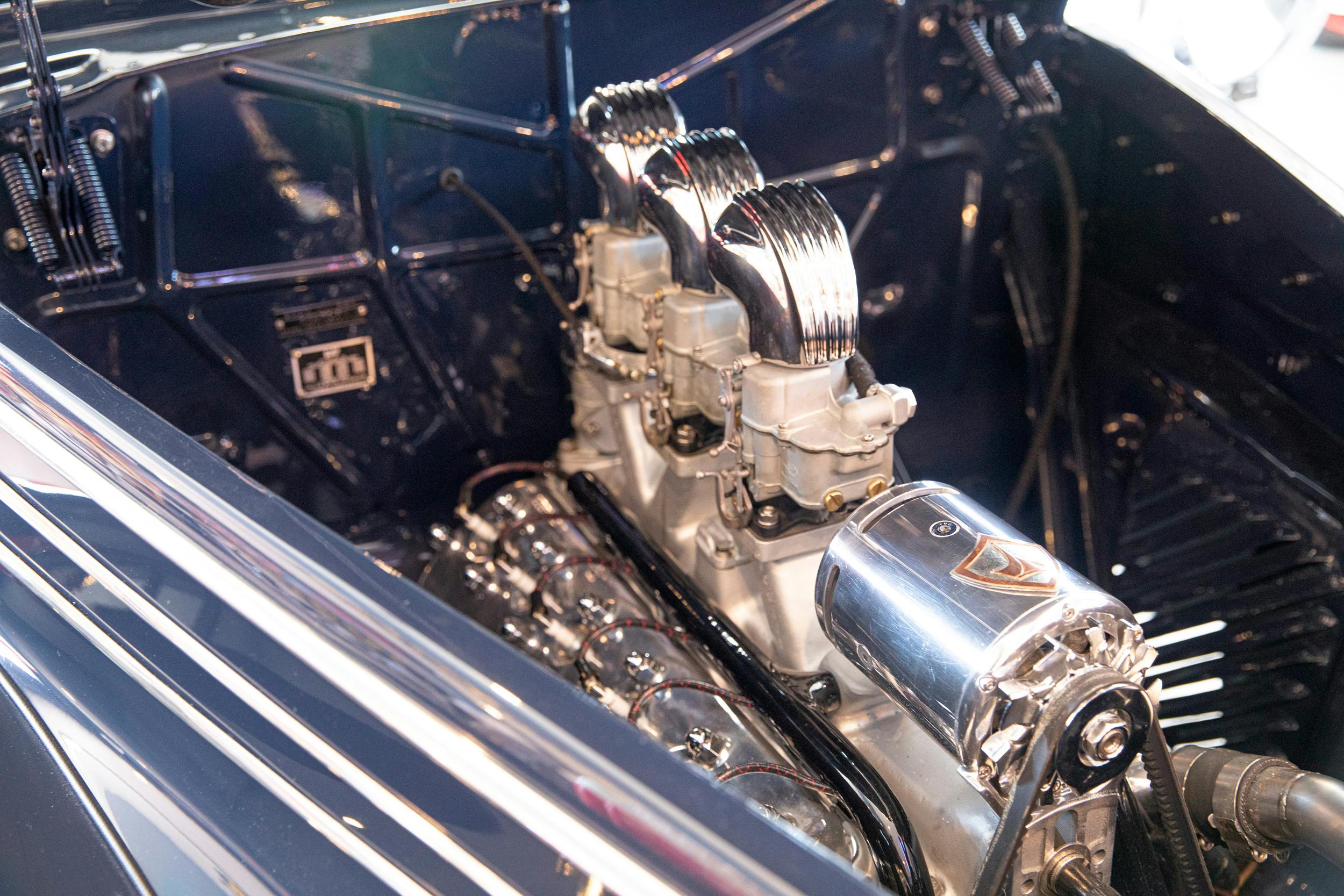

Capitalizing on his midlife success, Teutul has become a car collector himself. “You gotta remember,” he says. “I didn’t collect anything [cars] before 10 years ago.” Having recently turned 50, Paul Jr. isn’t old as car collectors go, but he is a unicorn, with a taste for 1940s Delahayes and prewar Lincolns. These cars are considered out of fashion among the current collector crowd, he’ll tell you, because most buyers don’t appreciate the metallurgical craft that was involved in their creation. “I love uniqueness, rarity, and beauty, and in that combination,” Teutul says, elaborating that cars with curving, cresting metal visibly display the mastery that went into forming them.

Teutul also sees labor in the shapes. “There’s a lot of shrinking and stretching of the material. It’s not like just making something round or in one direction. It’s a compound form, and that takes a very, very special skill.” Nearly a century ago, Teutul explains, the talent necessary to turn metal into rolling sculpture was relatively common. Today, however, he fears it’s becoming a lost art.

As a collector, Teutul’s well aware that few millennials prize cars from the 1950s, let alone the ’30s and ’40s. Most of us crave the cars of our childhood, but Teutul? He’s fond of cars that his grandfather might have lusted after. He’s on his fifth 12-cylinder Lincoln Zephyr, and before that, he was into mid-1930s Hudsons. He says it’s all about craft. “The waterfall grille that Hudson did in ’36 and ’37? Man, I mean, they’re so art deco.”

Sure, Teutul appreciates a perfectly mint muscle car, but to his eye, the scarcity and handwork of coachbuilt cars matter more. This explains why he once owned a rare 1936 Hup Aerodynamic that he sold for a healthy profit to Nicola Bulgari. He now regrets the sale. “Every car I sell is the ‘one that got away,’ but I’m a businessperson first.” He hesitates. “I mean, I am, but when I tell people I’ve had five Lincoln Zephyrs? It’s just that I’m also very passionate and emotional.”

Stop the record: Teutul did say he is a businessperson first. Over the past eight years, he has driven up the price of the Zephyrs he loves the most. In the mid-2010s, he landed on one for about $75,000 and “shined it up a bit and sold it for $150,000. And I was, like, well, ‘I’m doing this again, right?’ the following year. I did the same thing for, like, five years.” He paid $94,000 for another that sold for $187,000. There was only one problem: “I drove the market on those things literally to the point where I’ve just about driven myself out.”

His Zephyr obsession is perhaps most strikingly realized in his current 1939 Zephyr Three-Window Coupe. Teutul pulled the fenderline from front to back and converted the car to suicide doors, then added a “speed fin” to the roof, which looks exactly like a feature you would’ve found on some coachbuilt cars of that era. He also lowered his Lincoln a smidge. “The stock height’s like 12 inches. There were a lot of dirt roads at the time, so that was practical, but they look too tall.” Still, he was careful not to go too far. “I just wanted to put my fingerprint on it but not make it modern in any way.”

Teutul’s like a lot of people: He’s in love with the cars he has, including a 1914 Cadillac Speedster, but he wouldn’t mind owning something he can’t afford. He lusts after the 1947 Delahaye 135MS Narval Cabriolet that co-won the spotlight as Best in Show at Amelia Island earlier this year. The other car that took top honors was a 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO. Not that the Ferrari isn’t rare, but he appreciates the scarcity of the Delahaye more—and he thinks that’s also why his Lincoln is important. “When people are strolling the lawn and they’ve flown in to buy a Ferrari, then they walk up on this art piece Lincoln, they’re floored by the beautiful flowing shapes that just go on for miles.”

He wishes more people of his generation saw that, but he’s also well aware that what he says and what he crafts don’t entirely mesh. He has taken heat for making bikes that aren’t rideable, but he softly suggests that those critics are not really seeing the work. He notes that the ultrastretched chassis are purposefully beyond what you’d see on the street and that customized, extraordinarily sized wheels aren’t built for riding. They’re there to show proportion. Riding? That’s not the point: The bikes are canvases.

Then again, “I’m a history buff,” he says, so at The Amelia this year, he was one of the judges who gave the Motorcycle Best in Class nod to a 1973 Ducati 750 Super Sport with a racing pedigree (and only one of three in existence) over a “prettier,” more classic Benelli Leoncino. To Teutul, once again, his filters of history, beauty, and scarcity all float to the top.

So, although Teutul’s drives and influences are often contradictory, he’s sharp enough to know it. The work he does requires invention and circus-like instincts. Yet he collects vintage automotive memorabilia and is never happier than when he finds old bikes with patina and doesn’t have to do anything but get them running. He sees himself as a regular guy, happily married to his wife, Rachael. He wants to let their son, Hudson, find his own way. Hudson doesn’t care about ball sports like his dad did, preferring to surf, and Teutul is fine with that.

What could rock his happy-family boat? Teutul’s about to put both his kid and his wife on the air for a new reality show he and Rachael are co-developing. He wouldn’t cough up details, but as we went to press, Teutul said it’s on its way to TV screens soon.

If all that speaks to Teutul’s to-and-fro nature—the showman and the family man—he’s humble about this, too. He’ll own up to not having all the answers, just as he’s happy to ask a fellow judge at a concours about bikes he doesn’t have mentally archived. He believes the secret sauce of American Chopper is that viewers came for the metal but stayed for the relationships—just as car collectors do at any concours. “The show was sensational and, sometimes, ugly,” he recalls. “But we were salt of the earth people. I think maybe people who felt like they were dysfunctional, we helped them feel more normal, and they just loved us for it.”

I’m not big on “celebrity”, but I did enjoy watching Paul on his shows. His bikes aren’t really my style, but I appreciate his talents. Sounds like he has turned his hot-headed self into a mature and successful businessman and husband. Good on ‘im!

In the early days of American Chopper I remember watching Jr installing a rear axle on a bike. It wasn’t going well so the solution was a bigger hammer to pound it in with. About a 5 pound hammer IIRC. I cringed and thought; “I wouldn’t let him work on a wheelbarrow of mine”. While his designs were eye catching, his mechanical skills left something to desired.

I will assume his skills have matured and he no longer works that way.