The Day Horsepower Died

This story first appeared in the September/October 2024 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Join the club to receive our award-winning magazine and enjoy insider access to automotive events, discounts, roadside assistance, and more.

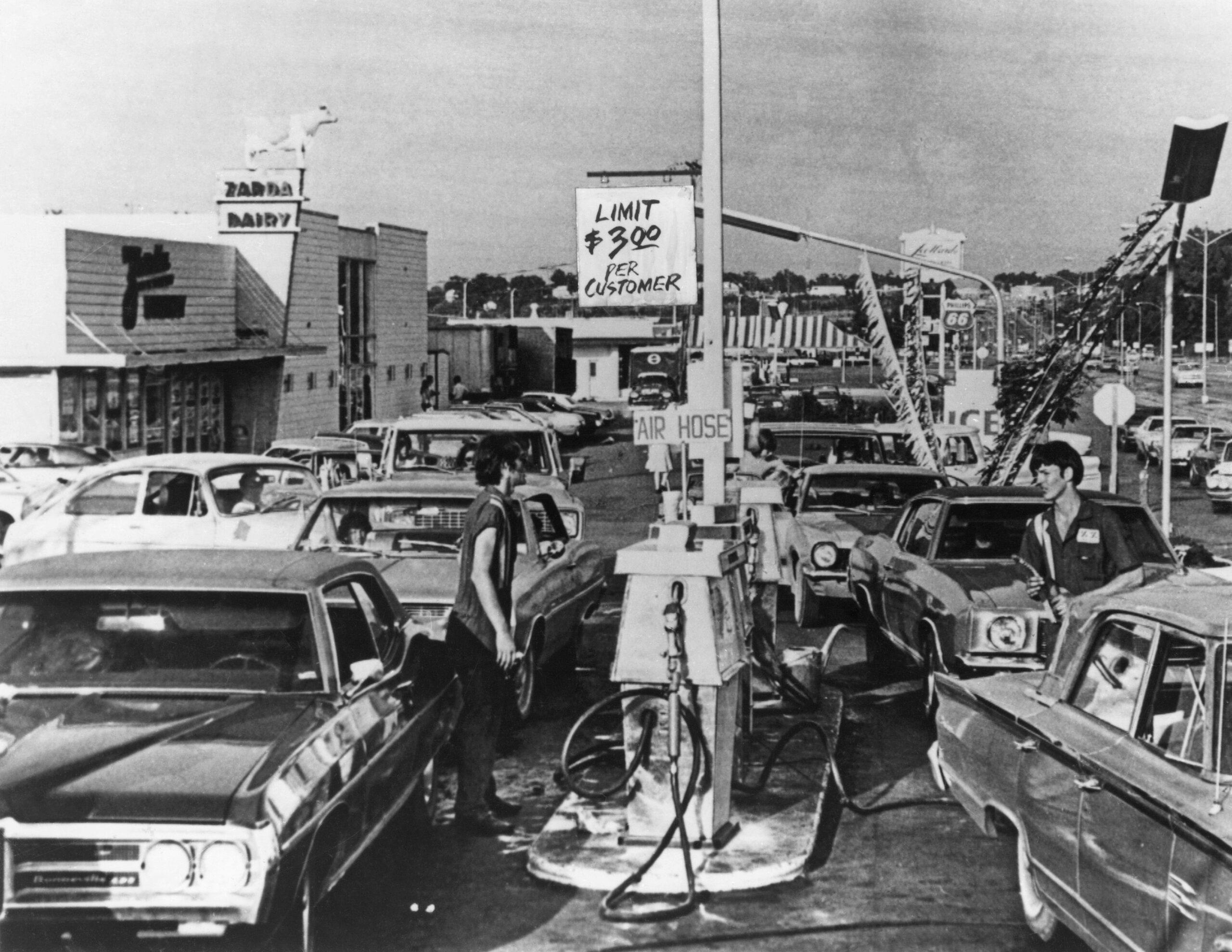

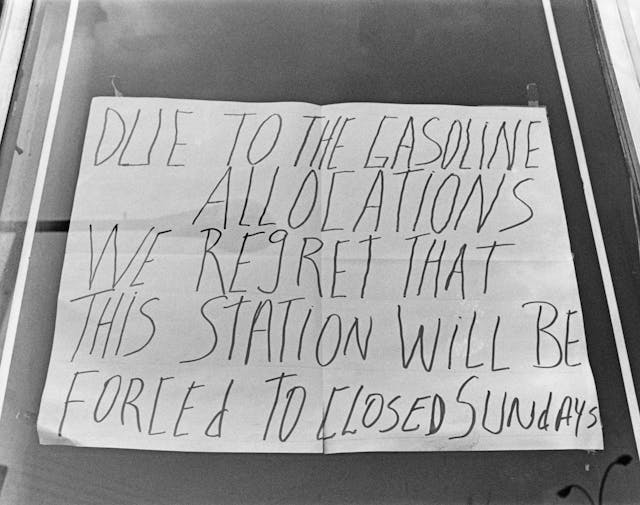

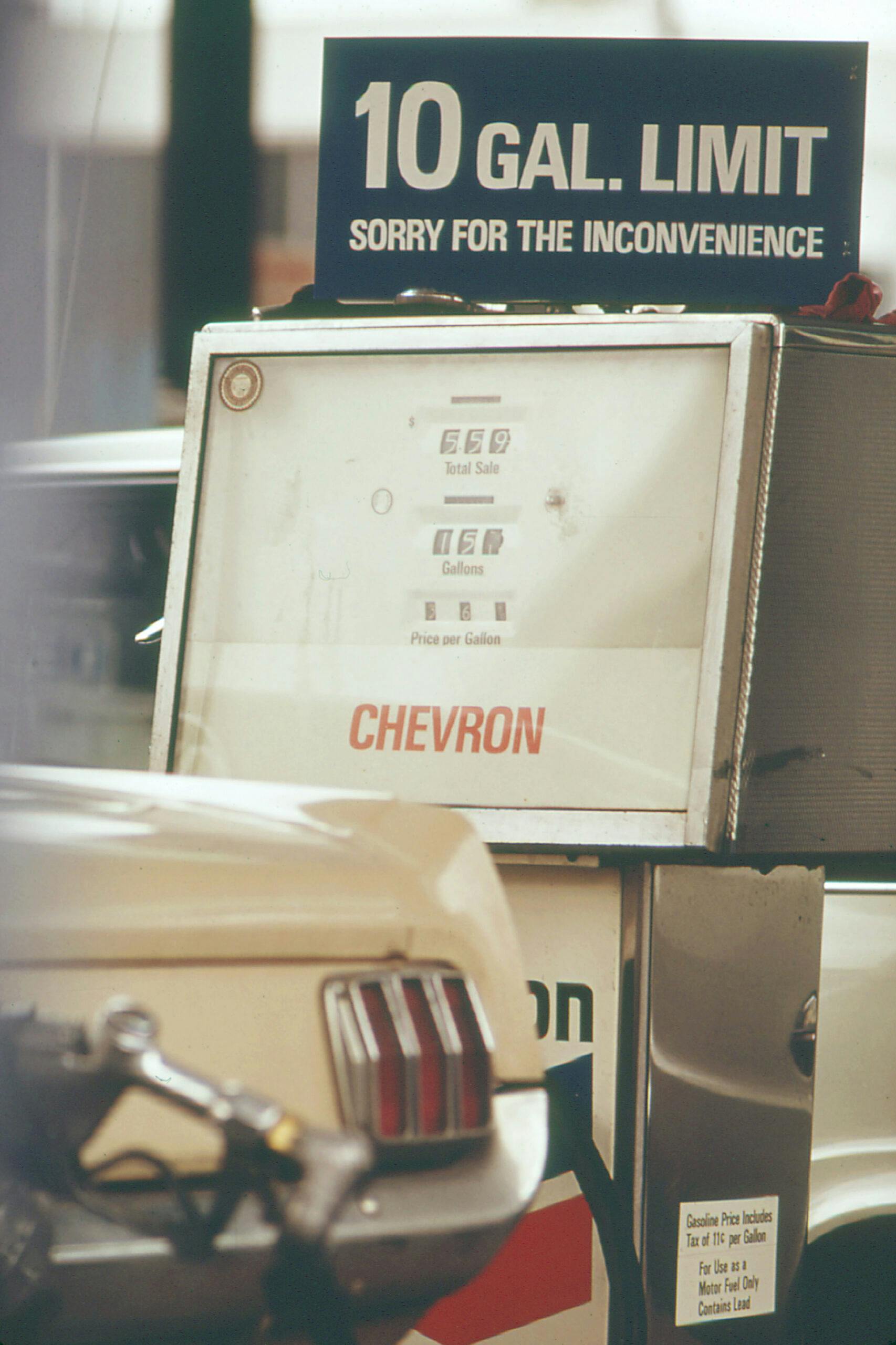

It was 51 years ago on a busy Saturday in September that the pumps went dry at Barker’s Texaco on East Independence Boulevard in Charlotte, North Carolina. Owner Aaron Barker scrawled a sign that read “Out of Gas,” hung it in the window, and sat down at the counter. Over the next two days, during which the station would normally have rung up around $1600 in sales, he took in just $82. “You work yourself to death for years, both for yourself and for Texaco,” Barker said at the time. “Then they’re yelling ‘allocation, allocation’ and the next thing you know, you have no product.”

During the previous two decades, Americans had grown accustomed to driving big, powerful cars fueled by cheap gas, the spoils of victories in two successive world wars and the subsequent creation of the world’s greatest economy built on a bedrock of democratic principles. But in the fall of 1973, it all seemed to be coming apart. The cheap gas became scarce, the greatest economy in the world was spiraling into an inflationary malaise, and even the democratic principles were straining under the weight of the Watergate scandal.

It was, as Dickens might have observed, the worst of times. However, when humans have come face to face with the same imperative as nature’s other creatures—that is, to evolve or go extinct—we have invariably chosen the former. Though nobody knew it at the time, when the tunnel seemed to lead only into darkness, the automobile’s future was bright, and it was exactly the oil crisis that made it so.

The one-minute sketch of American history has the big-block, Hemi, Six Pack, Cobra Jet 1960s crashing headlong into the Arab oil embargoes of the dreary 1970s. It’s not untrue, but it misses a lot of the story. In fact, warnings of an impending energy crunch were sounded as far back as when the Beach Boys cut their first album, Surfin’ Safari, in 1962. America’s oil consumption was doubling roughly every 10 years at that point and nobody seemed to care. “Left to our present profligate ways,” observed the syndicated columnist William Hines in 1966, “we may very well doom our remote decedents to a misery that would probably be avoidable with a little sensible work and planning now.”

By the dawn of the 1970s, when an America representing less than 6 percent of the world’s population was consuming 60 percent of its oil, the “sensible work and planning” had yet to happen. Brownouts from electricity shortages had already struck major cities in the summer of ’69, and coal and natural gas producers were warning of dangerously tight supplies. Meanwhile, it was generally believed that the oil industry would soon reach the production limit possible with the known reserves—the so-called peak oil theory—so it was restrained by regulation in how much it could extract from government-leased land.

At the same time, a burgeoning environmental movement, spurred by a massive oil spill off California’s Santa Barbara coast in January 1969, was stiffening public opposition to expanded oil production, crystallizing in a two-year moratorium on offshore drilling. Nuclear power, seen as the great savior in the 1950s and early ’60s, also landed in the environmentalists’ crosshairs, and new atomic projects became bogged down in regulation and community resistance.

With the Alaskan pipeline still in its planning stages, and with spot gasoline shortages already cropping up in some places because of a regulated distribution system that could not respond well to shortfalls in local supplies, the administration of Richard Nixon looked overseas to fill an increasingly ominous gap between supply and demand. However, the nations that in 1960 banded together in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and one of its later off-shoots, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), began to see their sticky black blessings as not just an economic windfall but as a powerful political cudgel against the West.

Thus, America’s energy situation was already a teetering house of cards in October 1973 on the eve of the holiest day on the Jewish calendar, the Day of Atonement known as Yom Kippur. On October 6, as Jews around the world went to synagogue and headlines trumpeted the latest legal travails of Nixon’s embattled vice president, Spiro T. Agnew, a coalition of Arab states launched a surprise attack against Israel. A desperate three-week struggle ensued that forced both the United States and the Soviet Union to rush military aid to their respective allies, and the moment for the oil cartels had arrived.

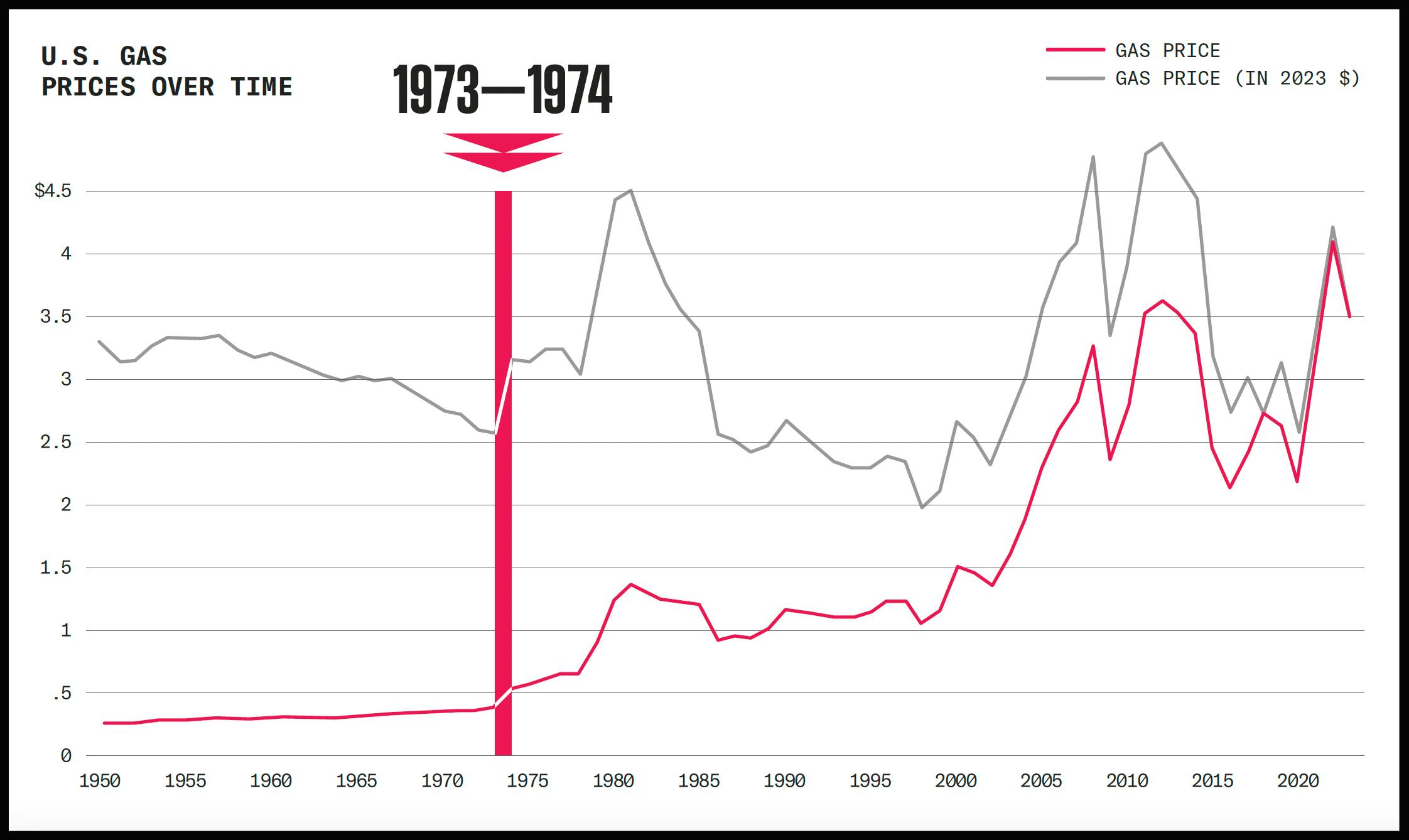

On October 19, the members of OAPEC shut off oil shipments to the United States while also cutting production, causing the worldwide price of oil to spike. Although imported oil only represented 10 percent of U.S. consumption—and not all of it came from the Middle East—the embargo was enough to cause havoc in the nation’s already-strained supply. The price of gas practically doubled overnight in some places, from the 35 cents a gallon it had been more or less since the 1950s to, in some places, as high as 80 cents. As we know from recent post-pandemic experience, rising gas prices force up the price of everything. Nationwide, for example, the price of milk went up by a third that October. And with winter approaching, America suddenly faced a daunting choice between having enough gasoline for its cars or enough heating oil for its homes.

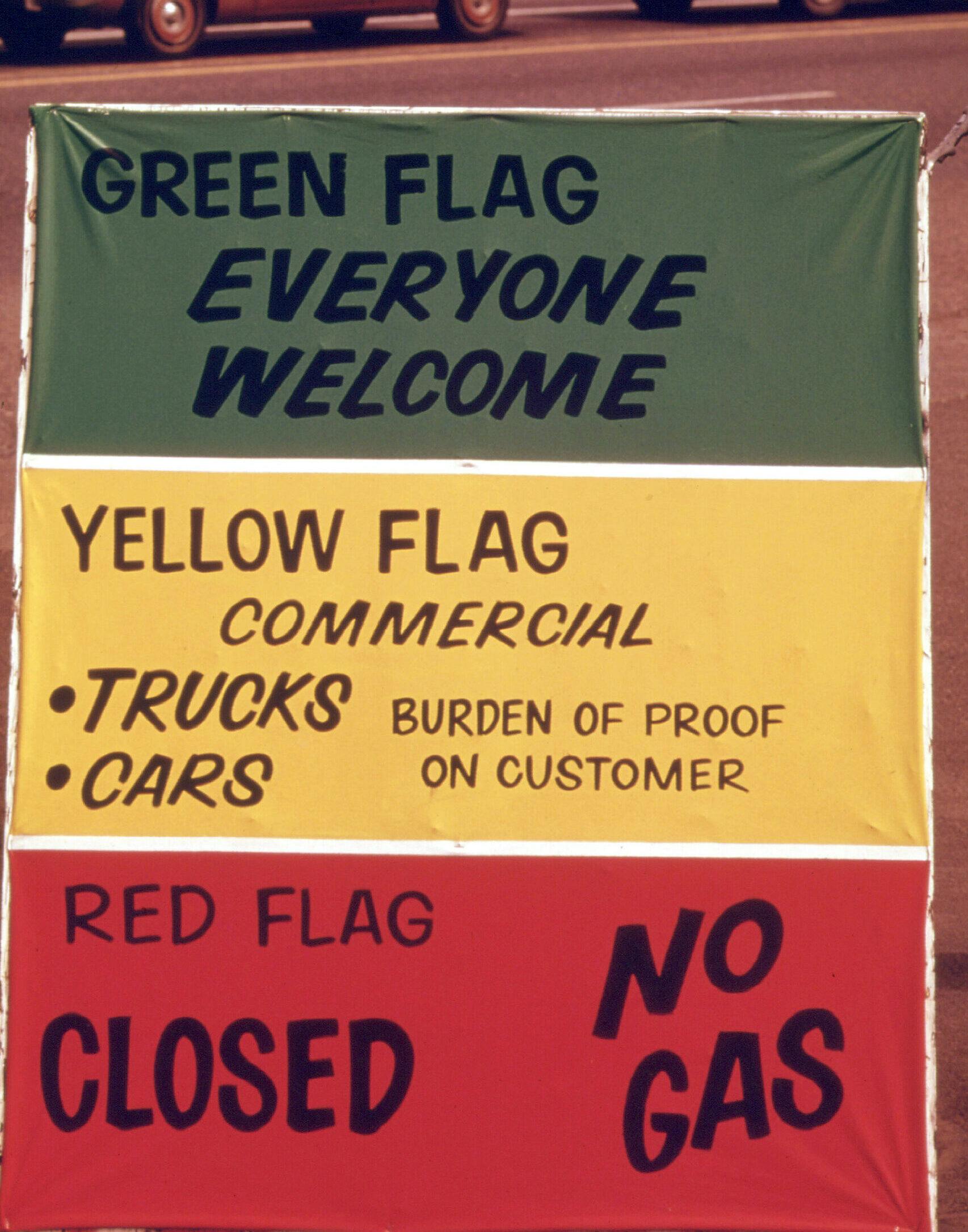

Extreme measures were explored, some significant, such as Nixon calling on gas stations to voluntarily close on Sundays, thereby discouraging unnecessary pleasure driving (it was noted sourly that the flotilla of helicopters bearing Nixon and his entourage to a Thanksgiving retreat at Camp David burned 600 gallons of fuel, in addition to the gas needed to move his multiple limousines there). Some acts were obviously performative, such as Republican Connecticut Governor Thomas J. Meskill announcing that the state would sell off its own fleet of Cadillac limos. World War II–style gasoline rationing was proposed—and it was reported that New York’s mafia crime families were already lining up printing presses to produce counterfeit ration coupons.

Out on the farm, ancient wood-burning steam engines were pressed back into service. Two partners in a restaurant near Indianapolis started commuting in a 1911 Oldsmobile because it reputedly got 50 mpg. Meanwhile, in Olympia, Washington, the Boone Ford Town dealership advertised a deal on auxiliary fuel tanks for your pickup, $90 for a 16-gallon tank or $155 for a 32-gallon, because “there’s no telling where you could be stranded someplace where all the gas stations are closed.”

Fingers pointed in every direction. The government blamed the eight largest oil companies in the U.S. for monopolizing the industry and manipulating prices. Oil companies blamed government regulators as well as the environmental movement for curtailing drilling (does any of this sound familiar?). Florida official Robert Vernon, head of the state’s Interior Resources Department, called out Detroit for building high-horsepower gas guzzlers. “Those monsters people travel to and from work in ought to be eliminated,” he fumed to reporters.

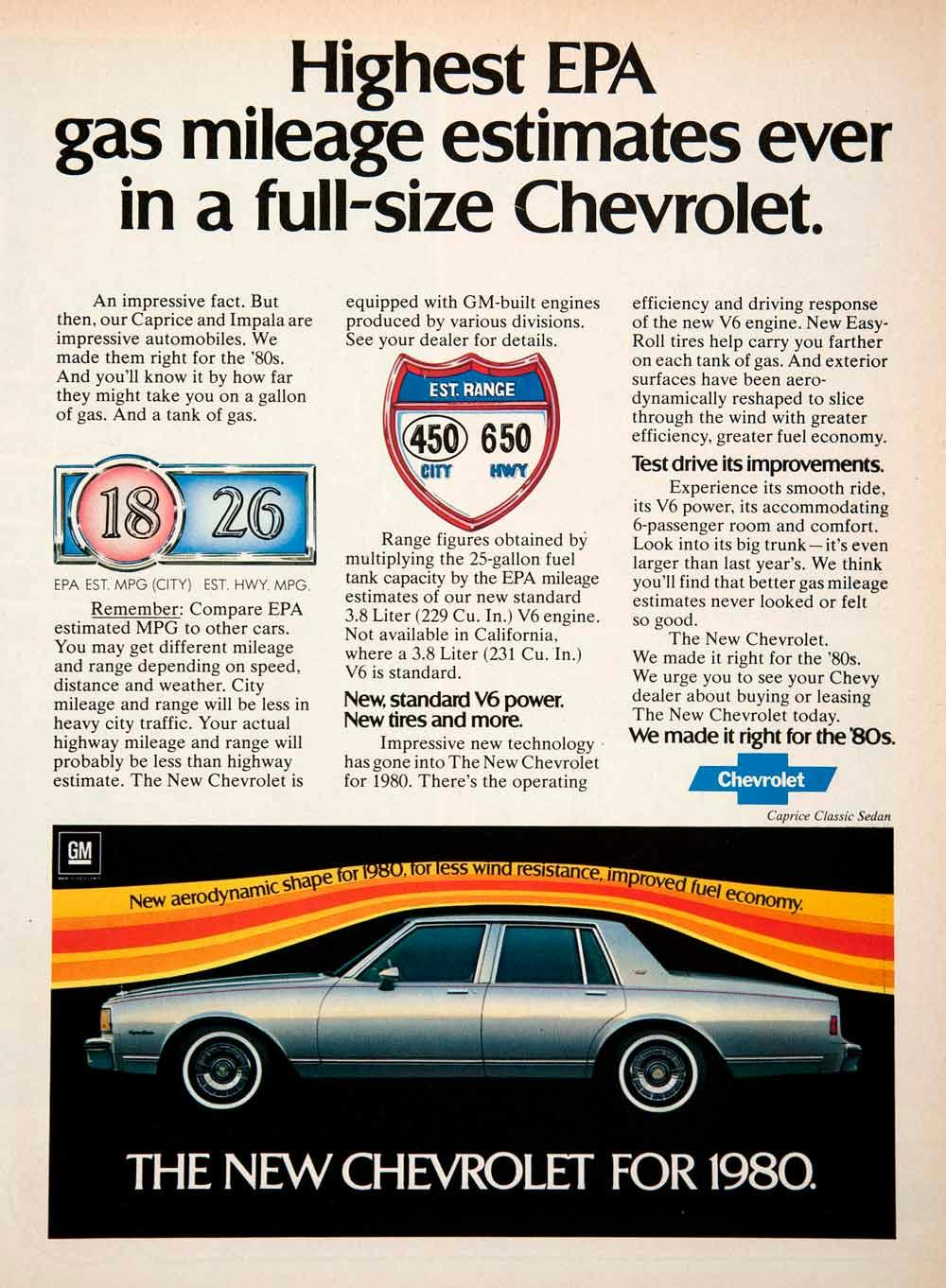

It must be said Vernon had a point. The newly created Environmental Protection Agency noted that most of the new 1974-model cars were only good for mid-teens fuel economy, specifically citing the dismal performance of certain models in urban driving: Ford’s Torino six-cylinder, 14 mpg; AMC’s Gremlin six-cylinder, 16 mpg; Cadillac’s DeVille with the 472 V-8, 9 mpg—good for a mere 247 miles on its 27.5-gallon tank. Even new fuel misers such as the Ford Pinto and Chevrolet Vega, two of Detroit’s subcompact answers to the imports, were said to achieve just 20 to 23 mpg. Congress subsequently passed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, establishing the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard that to this day requires automakers to meet ever-escalating mileage standards or face huge fines.

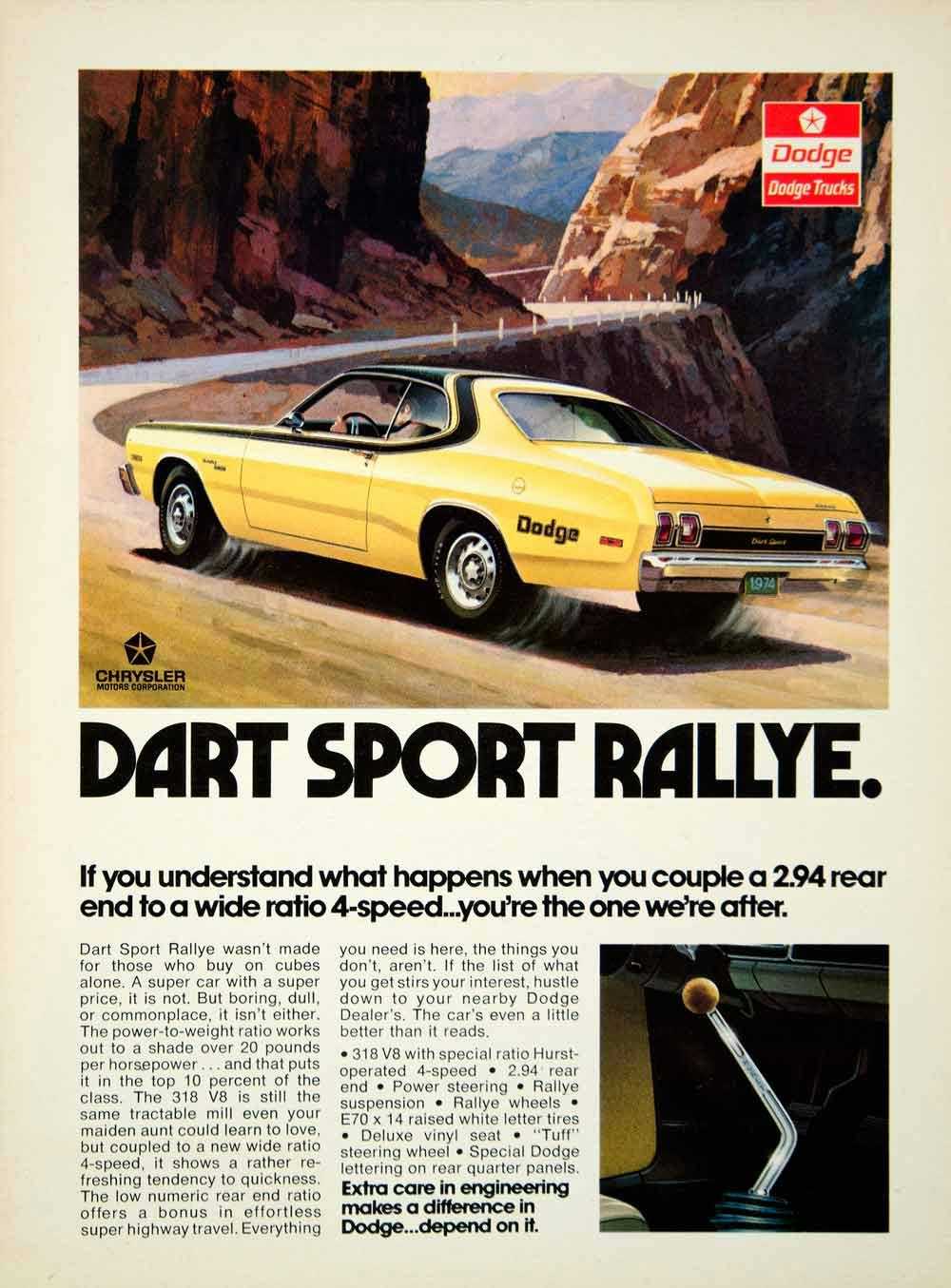

Horsepower was entirely forgotten, replaced in car adverts by fuel economy as the single most important vehicle stat after its price. Another victim of both inflation and the energy crisis was the convertible. In 1965, Detroit’s three native carmakers plus AMC offered 57 convertible models that garnered more than a half-million sales. By 1972, only 60,000 buyers a year were going for ragtops. On July 5, 1973, at 10:40 a.m., Ford built its “last” convertible, a ’73 Mercury Cougar, a signal that the era of fun was over (a decade later, the ’83 Mustang returned Ford to the soft-top business).

However, Americans proved reluctant to give up their “monsters.” Sales of profitable large cars remained strong through the 1970s, even as new fuel-economy and emissions measures robbed them of power. “We build a car the customer wants,” insisted Buick general sales manager Frank Frost while unveiling the 1974 models, the most potent of which was the Riviera, with a 455 V-8 that made all of 210 horsepower to move its 4700 pounds. Frost added that Buick wouldn’t stop building such behemoths until “the customer tells us he is absolutely through with the many comfort and performance pluses of larger cars.”

By 1978, the customers seemed to be absolutely through. Imports had ballooned to nearly half of new-car sales in California while Detroit’s own small-car offerings were sagging in the market. Even the unions were haranguing the Big Three to get serious about downsizing, with United Auto Workers president Doug Fraser imploring the C-suite suits to act before more of his members were laid off. A second oil crisis, in 1979, ignited by the Iranian Revolution, hit a system that was still reeling from the first. That gallon of gas that had been 35 cents only a few years earlier was now $1.20, and there seemed to be no end in sight.

It cost the automakers an estimated $50 billion over five years to adapt, but adapt they did. Fuel injection combined with computer controls made engines more efficient as well as cleaner, allowing them to meet a seemingly impossible CAFE standard of 27.5 mpg by 1985. Turbochargers arrived in force in the 1980s to give four-cylinders the power of V-8s, and curb weights tumbled. The 1981 K-cars launched with the first four-banger from Chrysler since the 1930s and were more than a thousand pounds lighter than any sedan the company built in the 1970s.

All this economizing helped lead to a tumble in global oil prices in the mid-1980s, which led to a whole lot of fun cars being produced in the late 1980s and 1990s that were cleaner, more powerful, and relatively efficient. And, thanks to advancing technology, we’re still on a roll. The fastest mass-market car today, the Tesla Model S Plaid, burns no gasoline at all. Even the industry’s most horrendous guzzlers, such as the 6.2-liter Hellcat-powered Ram 1500 TRX (12 mpg city/highway combined), would only have rated about average in 1973 fuel economy terms. Meanwhile, the Ram’s tailpipe emissions are 98 percent cleaner, even as its 702 horsepower is more than three times that of the most powerful Detroit iron of the day. The onset of the electric era seems to threaten the relevancy of horsepower figures once again, but this time in a good way. The 2024 Lucid Air Sapphire is a luxury sedan rated at 1234 horsepower, a figure so lofty that it’s almost impossible to comprehend. If it were 900 or 1500, would it make much difference?

In our own time, when we seem to lurch from one crisis to another, we can take some comfort from what our history seems to be telling us. Which is that crises, in all their ugly, terrorizing, and brutal manifestations, are actually good for progress. In the auto industry, as well as in life, if you’re not moving forward, you’re sliding backward. The gas pumps may well go dry again, but the next time it happens, it’s possible that few will really notice.

Really did not die.

There were some set backs but in a strange way the things companies did yo make more efficient engines had left to 300HP 4 cylinders and now 1064 HP Corvettes. .

Would we have Turbo, DI and all the advanced high boost and compression systems?

We truly are in an era of some of the best engines ever. But if someone dies not step in soon we may lose ICE long before it should die.

Well it was pretty dead there for awhile – least in factory new car form. Didn’t take too long for the O.E.M.s to start bringing it back to life, thankfully. The innovations you mention do indeed owe much of their current HP “life” to that period.

I was born in the early 70’s so my first cars as a little kid were not the most impressive. Little me though still loved them regardless. It’s amazing how things started to recover in the 80’s though.

I remember the $5 limit at the pump, obviously it bought a lot more fuel than today.

I was in the Navy, stationed in Charleston, SC, in 1973. Even though it was hard to buy gas (gas lines, stations closed due to no gas, strict limits on sales, etc), when our ship went to sea we passed lots of oil tankers anchored off shore waiting to unload — but they couldn’t come into port to unload because the oil tank farms were all full to capacity. It was very obvious that at least some of the oil crisis was manufactured by the oil companies themselves.

Heard the exact same story from a friend’s father, who was a navigation officer aboard tankers in the 60’s and ’70s. He said that before Oct. ’73,it was unusual to spend more than a day waiting offshore. Suddenly, not only were tankers being held offshore USA, but sailings from the source countries (especially those in OPEC) were also being delayed, and ships en route (including the one he was serving on) were being told to slow down.

I also had an uncle who ended up being a VP of Conoco during this period, and if he was a typical example of oil company executives, you can probably believe almost anything bad that anyone ever told you about oil companies…

“The ram Trx at 702 hp was 3 times more than than the most powerful Detroit iron of the day”. What day would that be? Multiple cars from multiple manufacturers in the late 60’s and early 70’s were rated by both the NHRA and the manufacturers well in excess of 400 hp! Maybe I just don’t understand this new fuzzy math!

I think they are referring to cars from the mid 70’s after the oil crisis : ie a 455 engine with 210 hp

He said 1973,not earlier which means at that time vehicles were indeed only making maybe low to mid 200s from large displacement engines and as an extra, 300 hp back then was not as powerful as 300 hp now! You should no that.

The difference in Net VS gross Horsepower, its quite a big number change

I was glad that I had bought a 1969 Beetle as my first car, at age 18, in the summer of 1973! We never had rationing or even/odd days in my area, but sometimes there were limits of 8 or 10 gallons. Of course, my tank only held about 10 gallons!

I remember a lot of those cars back then seemed to start leaking oil from the rear main seal after several years. The parking spaces at stores and office parking were very oil stained; not to mention the driveways at the houses. Don’t see that as much these days.

I remember feeling cheated. I had just started driving and the cost of gas shot up.

I still wanted to work on a project car. I had a good job and went searching for a good old gas guzzler.

In 1983 in the Auto Trader news paper, I chose one of three cars to go look at. All were Shelby’s.

I bought one and admit now I was very lucky to hold on to it and fix it up. Still have it. 1968 GT500.

Fourth paragraph:

“The one-minute sketch of American history has the big-block, Hemi Six Pack, Cobra Jet 1960s crashing headlong into the Arab oil embargoes of the dreary 1970s.” Hemi Six Pack? Maybe a comma missing? Hemi, Six Pack……

Too me, the worst thing that came out of the Arab Oil Embargo was the dreaded 55 MPH nationwide speed limit. With that as the national speed limit, there was no need for horsepower. All cars would get decent enough fuel economy, even if shaped like a brick, which many were. So when they lifted the 55mph limit, evolution again took place – engines with better efficiency, reliability, horsepower and cars with better aerodynamics were the results. Cars today are phenomenal compared to the 70s, but unfortunately, few garner your attention.

Fantastic article, Aaron!

An important history lesson for some, and a reminder for a septuagenerian like me.

Most importantly, it shows the amazing progress made all across automobilia.