Experimental Creativity: The Early Days of Nissan Design International

The year 1987 was a particularly gratifying one for Nissan’s American design staff. Just seven years earlier, the company’s first U.S.-based designers had sketched in a house next to the Empress Hotel in La Jolla, California, and then in rented studios near Miramar Air Force Base. Now the cars they created were real. The Nissan NX Pulsar Mk2, the Hardbody pickup, and the original Pathfinder had started rolling off the line months earlier to rave reviews and awards, and Nissan Design International (NDI, as it was then known) had earned a reputation for creativity and influential ideas.

NDI’s architects were former GM designer Jerry Hirshberg and Nissan executive (and architect by training) Kazumi Yotsumoto. They were assigned by Nissan president Takashi Ishihara to establish a design studio in Nissan’s largest export market, mostly to break free of what Ishihara saw as stifling internal politics and conservative tastes at home, but also to respond to Toyota’s Calty studio. Yotsumoto lured Hirshberg away from what the latter described as “the world’s mightiest corporation” with the promise of creative freedom, including the freedom to create a highly collaborative work environment unlike other car design studios.

It was a huge gamble for Hirshberg and the first lieutenants he recruited from GM, designers Allan Flowers and Tom Semple, but it paid off. NDI, known as Nissan Design America since 2002, is still turning out pretty cars, and in the 1980s it quickly established a much more direct relationship with Nissan’s production cars than Calty did with Toyota’s. NDI’s unconventional approaches and cool styles did just what Ishihara intended—create a more daring design culture on both sides of the Pacific.

As Hirshberg recounted in his 1999 book, The Creative Priority, this wasn’t an easy process, but it was lots of fun after the initial struggle. But it’s one thing for the boss to tell an over-arching story of how a business works. I’ve always been curious about what it was like for the creators themselves. Fortunately, Flowers graciously agreed to tell me all about NDI’s early days, how much of a leap it was from the familiar world of GM, and the culture that produced the Pulsar NX, Pathfinder, and other NDI jams.

The Defectors

Hirshberg and Flowers both went to work for GM right out of design school in 1964. By 1979, Hirshberg was Buick’s chief designer, and Flowers was the division’s assistant chief. Both had worked on serious blockbuster cars, like the 1971 Buick Riviera and 1976 Buick Regal, and their designs would be on Buick lots into the mid-1980s. Semple, who joined GM in 1967, was assistant chief designer at Chevrolet.

That summer of ’79, Hirshberg was approached by a headhunter for the Nissan job and at first dismissed the call as a prank. It wasn’t, and the second call set off seven months of interviewing and negotiating with Nissan, and not just for himself. “[Jerry] wanted to bring along people who he’d worked with and knew and trusted. He had talked to Tom and me for months about it and about us with Nissan, but neither party could act until he actually accepted the job and was hired.” One morning in February 1980, Hirshberg took the job and resigned from GM.

“This sent a shockwave through GM. They’d never had a chief designer or anybody at that level leave, let alone for a Japanese company, and it was shocking even when people left for Ford or Chrysler. It was big news back then, and everyone immediately started asking, ‘Well, who is he going to get to go with him?’ Tom and I both got roped into those discussions and played dumb about it.” That was on a Tuesday, Flowers recalls. By Saturday, they both had job offers.

Nissan’s studio would be in California, and there was no guarantee that the project would work out long-term. Following Hirshberg was a one-way decision. Once gone from GM, returning would be impossible, and the change also meant uprooting family and friends. “My kids weren’t thrilled, but it was February in Michigan, so my wife and I thought California looked pretty good.”

As Hirshberg later related, GM’s design culture had also grown stiff and rigid after decades of market dominance, and bean counters increasingly watered down its designs. Nissan was a chance for something entirely new, and Hirshberg had negotiated many things with Yotsumoto that spelled success, including the California location. It was chosen because of its proximity to a vibrant car culture and its distance from established design cultures.

“We were familiar with Calty and [fellow ex-GM designer] David Stollery, who designed Calty’s first production car. And Yotsumoto had already established the business, so we knew what it could look like. However, Jerry also negotiated for two studios and an engineering component to help ensure the cars it created would be production work, not just concepts and wallpaper. From our perspective, it seemed like Nissan and Yotsumoto genuinely wanted a U.S. viewpoint and new ideas about how the design process should work, not just different drawings.

“The following Monday, Tom and I had breakfast at the Denny’s on Van Dyke Avenue near the GM Tech Center and talked about what was going to happen.” They walked to the office, said, “I guess I’ll see you later today?” and resigned. By March, they were in California.

The Early Days

“We were immediately involved in architectural discussions and even figuring out what kind of art supplies we’d need; there was a lot of work to be done right away.” At first, Flowers and Semple shared an office in a house on Silverado Street in downtown La Jolla. While they helped Hirshberg, Yotsumoto, and the rest of the administrative crew choose building locations, within a month, they were sketching. “We were still hiring modelers and engineers while planning the facility, but if you’re a designer, you want to be drawing cars.”

They quickly outgrew the house. “But Nissan had contracted some temporary space from an industrial design company called Tesa Design, run by a guy named—if I remember correctly—Tom Stevenson? He leased us a 2 or 3000 square foot studio, but he also provided some staff because he had modelers and designers who worked as contractors.” One of NDI’s most critical early hires, Bruce Campbell, came from Tesa and later played a lead role in designing the Gobi pickup, the NX coupe, and the Quest minivan.

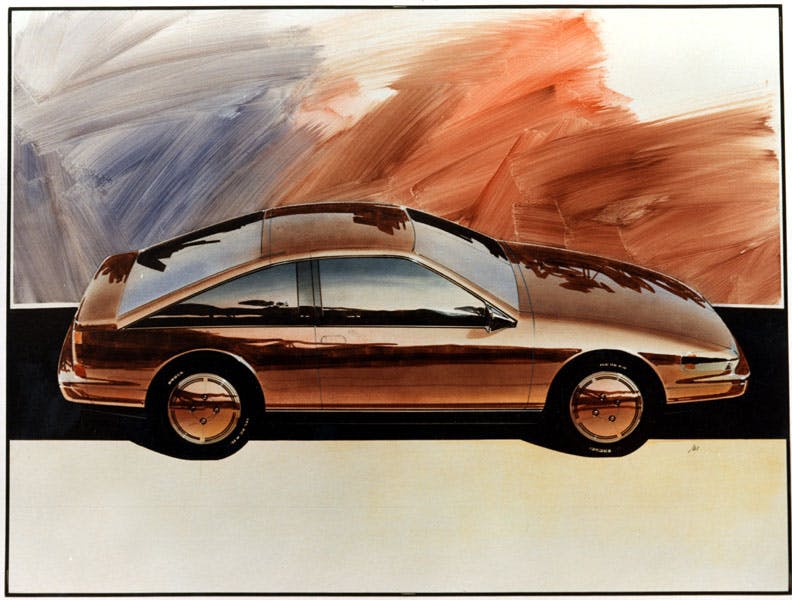

“After moving into Tesa we were ready to work, so we did three idea cars. One was a minivan. Chrysler’s minivan was still years away, but we knew vehicles like that were coming. Project two was a little commuter coupe, like a Honda CR-X but long before that came out. The third was a new Maxima, because we all thought the [1980] Maxima was a very cookie-cutter car. We called it the ‘Tofu Maxima’ because of how square and boxy it was.”

After a few months at Tesa, the two studios that would be the core of NDI were established. “Blue” studio, led by Flowers, and “Red” studio, led by Semple. Some of the earliest production projects they were assigned were proposals for the Prairie MPV (aka Stanza wagon) and the Hardbody pickup. The former didn’t get chosen, but the latter did.

The radical early Maxima renderings didn’t make the cut, either. “We were always competing with the home studio in Japan, and on that Maxima, we knew it would be a hard sell, but that didn’t mean we were going to play it safe.”

In 1988, when the third-gen Maxima debuted, the influence of NDI’s earlier proposals was obvious. By then, competition with Nissan Technical Center in Atsugi was more like friendly rivalry, and collaboration was closer. NDI’s designers were also fascinated by the Japanese designs. “When the Pike cars (Nissan’s Be-1, Figaro, Pao, and S-Cargo) came out, we were really jealous of those,” Flowers says.

While this was going on, the actual studio campus was completed in early 1983. At first, a Japanese company, Kajima, was hired to design it, but the proposed building didn’t blend with the SoCal environment or suit the designers’ needs. “It looked like a 1000-foot-long Airstream trailer, but we wanted something more like a school campus. He’d never get away with this today, but Jerry insisted we could not work in this environment and found somebody else.”

Semple brought in an old Art Center design school friend, local architect Ken Ronchetti, who was then designing California coast mansions. “At first, Ronchetti was given permission to do the interior, but Kajima got frustrated with our demands, so he took over entirely.” Ronchetti designed the gorgeously understated concrete campus. It’s still NDA’s home today and a frequent backdrop for Nissan press photos. It featured two big studio spaces and a library, offices, and modeling, paint, and machining shops.

The Hardbody and the Open Environment

NDI’s first major concept car, the 1983 NX-21, carried some of that radical aero look, but the Hardbody pickup was the first production vehicle the studio created. In the 1970s, Nissan’s pickups had been so popular that they spawned Ishihara’s decision to build the company’s Smyrna, Tennessee, factory, and they were still flying off the lots in the early 1980s. But, Flowers says, the American buyers for these trucks mystified management.

“Their home market was work vehicles for farmers, but in America, the trucks were selling like hotcakes to people who barely used them as trucks.” For the D21-series truck, at first codenamed “Project 850,” Nissan decided to build two versions: one for America and one for the rest of the world. It was NDI’s first major project, and the need for such product tailoring proved the studio’s worth.

Both the Blue and Red teams worked together on the Hardbody, underscoring what Hirshberg would later describe as his philosophy of “hiring in divergent pairs.” Semple’s emotive approach gave the Hardbody its trademark muscular fenders (he sometimes called them “triceps”), while Flowers’ more Bauhausian side informed the cabs and beds, but the whole effort was collaborative. Nissan chose Red Studio’s truck, but it used the back half of Blue Studio’s version.

When NDI’s designers were not working on cars, they were flexing their creativity on other projects: furniture for preschool kids and medical equipment for Eli Lilly. The kiddie furniture proved a particularly instructive challenge, pushing the designers to figure out how to relate to customers (in this case, little kids) who are a different physical shape from adults and see the world differently.

To choose colors kids liked, the designers examined the kids’ Crayola boxes—the shortest crayons were the ones they used the most, and those colors got the nod. “Interestingly, these were not necessarily the bright colors adults would expect to be favored but often relatively sophisticated color palettes—which then made it into the production program! This also made for a more soothing daycare environment. For example, the nap time cots ended up a calming soft gray-blue.” Flowers led that project, and designer Diane Allen (later of 350Z and Titan fame) played a key role.

Hirshberg also encouraged an environment of openness and radical candor. Unlike GM’s design reviews, where only senior designers and executives could weigh in, anybody at NDI could attend reviews and give their opinion, even if they weren’t designers. If secretaries or janitors thought a car looked wrong, the public might, too. Staffers were also encouraged to be multi-disciplinary. NDI’s in-house photographers were hobbyists whose “real” jobs were being a sculptor (Arthur Markiewicz) and an administrative assistant (Marsha Portugal).

Pathfinder and Pulsar

The Pathfinder grew directly out of the Hardbody, and all of NDI’s top designers, even Hirshberg, sketched on it. It was still early days at Tesa when the project began. At that time, “it took six months to a year to do all the model programs, so while we were finishing up the truck, we were already working on the Pathfinder. We all did sketches, but that triangular window was Jerry’s idea.”

Early on, the Pathfinder’s proportions were entirely different, tall and boxy like the Isuzu Trooper or Mitsubishi Montero, but dovetailing with the truck made it sleek. Designer Doug Wilson, who’d come to Flowers’ Blue studio from Chrysler in 1982 and sketched out the back of the Hardbody, did work in both studios and sketched many looks for the production Pathfinder.

Everyone was pleased with how it came out, Flowers adds, “But we had missed an important point. Everyone was driving these as if they were cars, which meant the four-door models soon became more important than the two-door, and while we really tried, it was hard to translate that cool roof to a four-door.”

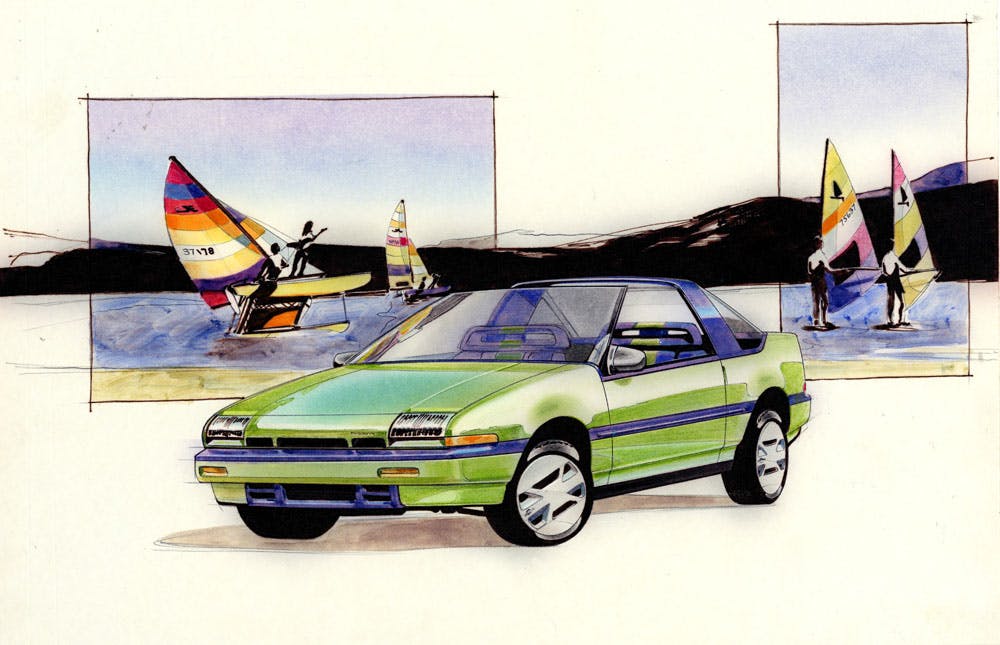

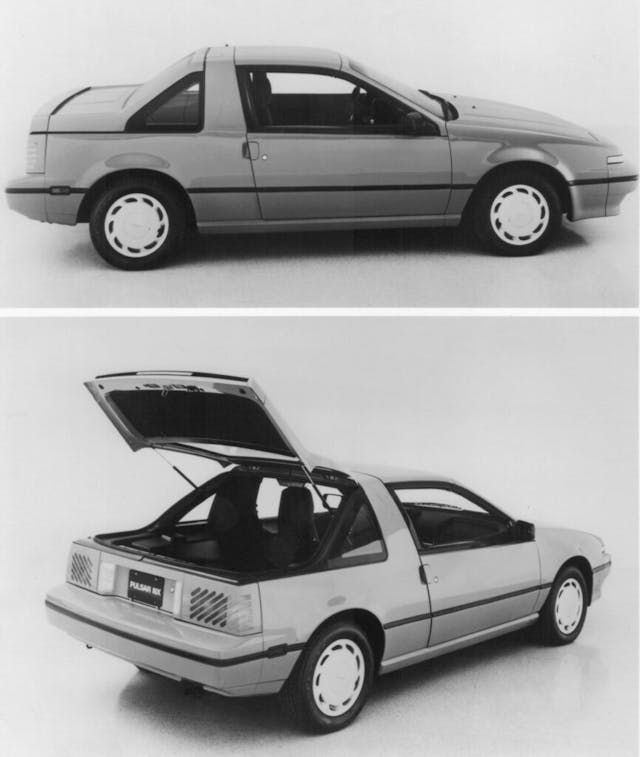

When the NDI campus opened, Blue Studio’s first project was the NX-21, largely sketched by Wilson. “We were all working together, though, because Tom also handled much of the modeling on that project.” Nissan liked the looks, and it formed the basis of what became the NX Pulsar, the first production car done entirely by the Blue team. “I was the chief, Bill Brown was the engineer, Doug was the designer and we also had Bruce Campbell on it. Doug’s sketches set the theme, and I did the front half of the car.”

The Pulsar was already at the early scale model phase when the famous “modular car” concept happened unexpectedly. “Doug was doing some sketches—he was always doodling—and one of them slightly changed the parting line on the hatch and colored it gray. While Doug was at lunch, Jerry saw this sketch, circled it, and wrote something like ‘Eureka!’ on it. Normally you don’t draw on other people’s sketches, but when the boss does it, it’s OK,” Flowers laughs.

“Jerry’s view was that it looked like a modular thing, which meant you could take it on and off and replace it. That wasn’t necessarily Doug’s intention with that sketch, but it worked. So then we did the Sportbak and T-tops, so you could make a full convertible out of it. That became the program overnight.” Management liked it and chose it over a competing proposal from Atsugi.

Once designs were chosen, team members typically spent many months in Japan during the productionization phase, and Wilson and Campbell went there for the NX Pulsar. This led to more cross-pollination with Japan. “There were also a lot of people sent back and forth. Many Japanese designers would come for six months to a year and work with us, including Toshio Yamashita, who designed the 1989 Z. Our competitions got fiercer, and sometimes they taught us lessons. There was a lot of mutual respect.”

For the company, this was the whole point, but even the designers got a great deal out of this creative oasis. Wilson, speaking of the NX Pulsar, told Car Styling Quarterly in 1989, “There’s no greater joy than to see one’s efforts appear in the product unchanged.”

These stories are great…Thanks for telling it.

Enjoyed the article, thank you ! I’ve owned a couple of 1st-gen Pathfinders – a 2-door and a 4-door – and always appreciated the combination of logic and the sexy fender bulges. I preferred the 4-door version for access and practicality, and I’d gladly own another. To my eye, it’s a very tidy & clean design, best accentuated by metallic colors.

Hirshberg retired and Nissan styling has never been as good since.

Great article. As an architect and car enthusiast coming of age in the late 80’s, early 90’s I remember how modern and fresh Nissans looked. Even today the Maxima 4DSC, four door sports car looks great with not an offensive line. Nissans of late are a hot mess and compared to the competition look cheap and overwrought.

This era of Nissan design was among their best. I miss the 80’s-90’s Nissan design and cars. Nissan today is a bland car company full of bland appliances I have no interest in. The New Z isn’t as good as it was but is at least interesting and the GT-R is now gone. Not much for an enthusiast there.

I’ve owned at least 30+ cars over the many years. My first and last new car purchase was at a Nissan dealership in 1987. It was a Nissan SE-V6 King Cab truck. I drove it 15 years and 140,000 miles. The only repairs I made were replacing oil sending unit and a couple of smog parts that had rusted and fell apart. I sold the truck to my neighbor in 2022. He drove it another 10 years and 100,000 miles. He eventually had minor issues with the truck. He gave it to a relative. I did see it once many years ago locally. Not sure where it is now.

I The truck was bullit proof for many years. No major problems ever showed up. Unfortunately, Nissan has not reliable the last 20 years. They are not what they used to be. I loved that truck!!!

This brought back a fond and foundational memory for me.

I was a 2nd year Junior College student in Fresno, the son of barely-English-speaking immigrants from Northern Spain (my dad, the stereotypical sheepherder who was 63 when I was born, and my mom, the slightly more English-fluent mom). Though they both had gone to school very little as children themselves (my dad, to the 2nd grade, and my mom, to the 6th), they had the prototypical American dream in mind for their kids: Go to college and study in one of these fields… Medicine, Law, Engineering or Business.

I grew up sketching cars with my middle brother (who, despite being an incredibly creative person, studied at the University of Pacific to become a Pharmacist). I was academically advanced (Lifetime- California Scholarship Foundation) but still was drawn to Automotive Design, a field that made my parents incredibly nervous. They, to their credit, did not force anything on me but (through my brother) I was told that I needed to prove that this would be a legitimate career for me (and determine how to pursue it).

As it turned out, I saw an article in one of the enthusiast magazines (can’t remember which one) that featured an article about CALTY and NDI, the two pioneering studios that were just opening in Southern California. The article provided addresses to both(!), so I sent a letter to each, seeking information on the field & educational paths to becoming a professional Automotive Designer.

I received a very nice letter from CALTY, though it was clearly more of a form letter.

From NDI, I received a personally-crafted letter from Jerry Hirshberg, himself. Perhaps not realizing the pandora’s box that he was opening, he closed it with an offer of “feel free to call me at (providing his phone number)…”

Being both desperate and naively-bold (despite being a shy kid, in most other ways), I called… Jerry answered and we had a great conversation about cars, what attracted me to them, and what his background was that brought him through a career at GM, to La Jolla. At the end of the conversation, he offered, “…if you happen to be in the San Diego area, feel free to call and drop by the studio…”

Little did either of us know that a few short weeks after that call, my brother (the Pharmacist-to-be) was awarded an Externship… at the VA Hospital in La Jolla (literally across the freeway from NDI). I, of course, offered to help him move down (loading his El Camino with all that he needed for the temporary assignment)… and called Jerry.

Jerry was very gracious and we arranged for a visit (on what I think had to be a Saturday, given that nobody was at NDI). Jerry met us and proceeded to take my brother and me through the whole facility, including not just the studios themselves (seeing the Hardbody scale models), but fabrication shops, paint booth, etc.

Truly mind-blowing in early 1983 (that MOAT!), and when we left (and returned to my brother’s apartment in University Town Center), he called my parents and told them that, if I was good enough to get into (what we figured was the best path) Art Center College of Design, what he saw at NDI suggested that this was more than just a legitimate career.

Based on that endorsement (impossible without Jerry Hirshberg’s graciousness), I applied/was accepted into Art Center and have now nearly completed a career that took me through a number of companies (including a first job in Japan) and a career path that took me into Product Planning.

I saw Jerry at NAIAS about 10 years ago(?), long after he’d retired from NDI/NDA (but still working as a consultant), walking the floor. I approached him, with less bravura than I’d originally reached out decades earlier, and introduced myself. I told him what I’d proceeded to do and that I considered his willingness to share with me as both foundational to what I’d done, and a model for how to help kids thinking about a career choice. He seemed touched that somebody would be so impacted and thanked ME.

NDI (and NDA) will always have a special place in my heart (yes, my heart) for this role that it played in my life.

Thanks for a great article about it.