Range Rover’s PR stunt to brave the Darién Gap was a baptism by fire—and swamp

In 1971, sport-utility vehicles were still decades away from their current market saturation point. The rugged workhorses were viewed mostly as task-focused conveyances for those whose daily driving habits took them well off the beaten path. A sea change was clearly coming, however. More and more Americans were drawn to Broncos, Blazers, and Wagoneers as vehicles for exploring their vast, open country. Paved roads were optional.

Sensing that the United States represented a vast untapped profit pool, British Leyland decided it had to get its brand-new Range Rover truck, launched in 1970, in front of as many American eyes as possible. How about sponsoring a daring drive across two continents, flirting with extremes at both ends of the temperature scale while putting nearly 18,000 miles of punishing Pan-American highway on a pair of Rovers?

Thus was born the British Trans-Americas Expedition, a stunt trip that would stretch from the Alaskan frontier to the tip of the Argentinean archipelago jutting out into the South Atlantic. Its mission: to captivate the press and the public. There was, however, the Darién Gap to consider.

Mind the Gap

The Darién Gap is, as the name suggests, a void. The Pan-American Highway is a network of roads stretching from Alaska to southern Chile, continuing uninterrupted from nearly pole to pole—except through the Gap. Located between Panama and Colombia, this Wales-sized melange of swamp, mountain, and jungle is the geographical bridge between Central America and South America. Crisscrossed by persistent river currents, the area is peppered with the remains (metal and otherwise) of those who have attempted to traverse it on four wheels. Despite several efforts since the 1970s to complete the missing link in the Pan-American Highway, none have been successful. Due to the cost of engineering roads in such terrain, as well as concerns over the environment, the spread of cattle-borne disease, and the preservation of cultural norms in the region, the Gap endures.

The primary challenge of the expedition was how the Trans-Americas team would survive 250 miles, off-road, through the Darién. This hurdle accounted for 1.3 percent of the adventure in terms of distance, but the remaining 98.7 percent would be an absolute cinch in comparison. The Gap alone would claim a full three months (or very nearly half) of the projected time allotted for the journey.

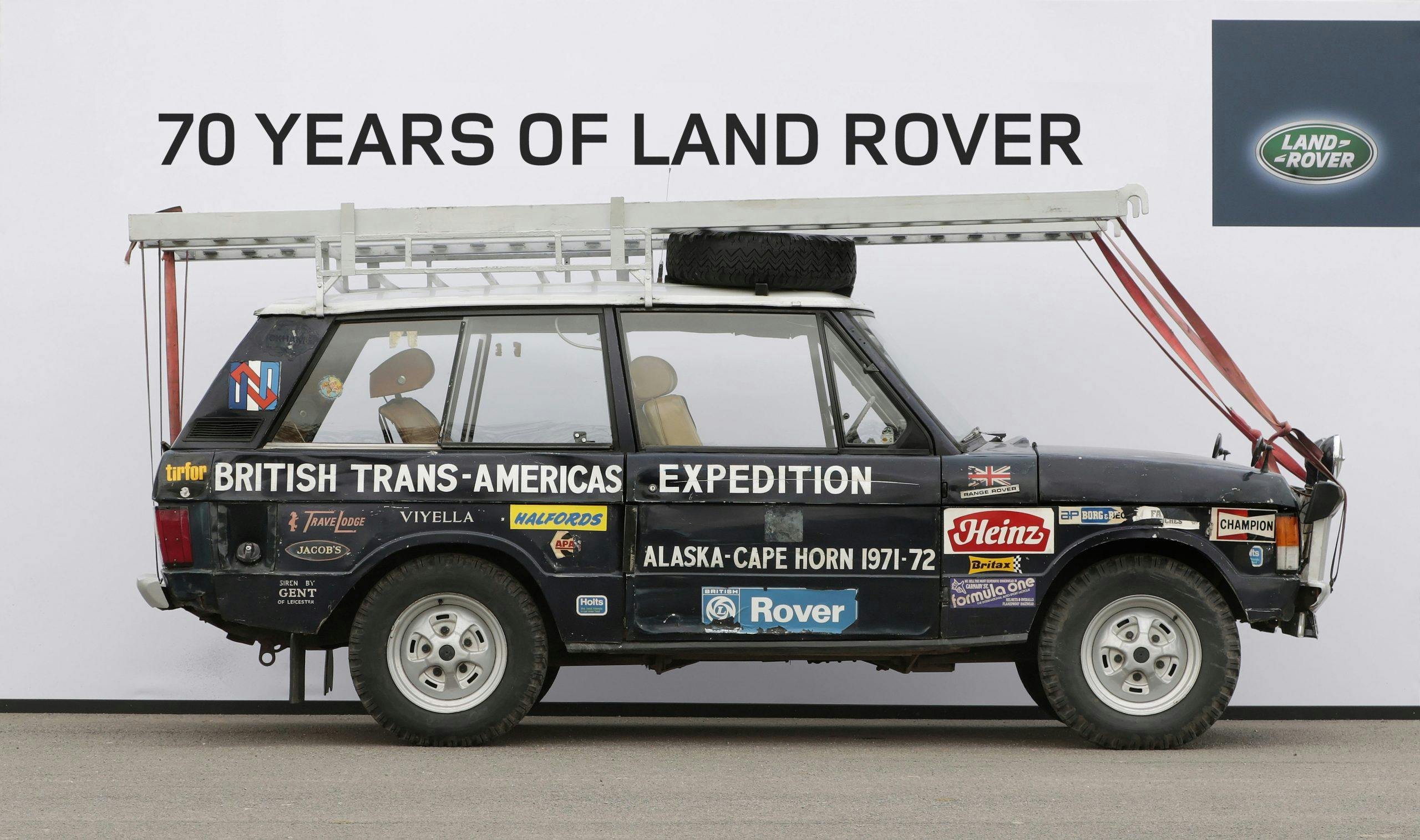

With this in mind, Land Rover blessed the pair of Range Rovers it selected for the project with an off-road makeover. Their survival through the Gap was paramount. While being careful not to introduce any beyond-factory upgrades that would transform the SUVs into too-obvious ringers, Land Rover outfitted both vehicles with winches, snorkels, auxiliary lighting, a battery upgrade, and undercarriage shielding for the fuel tank. There were also, of course, the kind of bush bars that would eventually become so popular on mall crawlers, but here they were fashioned by welding a set of bumpers on top of each other.

There was one more set of improvements made to Rovers that would turn out to be a ticking time bomb for the Trans-Americas Expedition: a set of Firestone “swamp” tires measuring considerably taller in diameter than what the SUVs got from the factory. They were so large, in fact, that cut-out access panels had to be fashioned into the fenders to ensure a speedy swap in any inconvenient off-road location.

Expeditionary force

To deal with the problems that would inevitably arise from such a bold undertaking, Rover enlisted the support of the British Army to get it through the Gap as painlessly as possible. Sixty-four men—drawn primarily from the Royal Engineers but also including a number of experienced expeditionary officers from the 17th/21st Lancers—were commanded by Major John Blashford-Snell. Both Colombia and Panama also contributed support personnel.

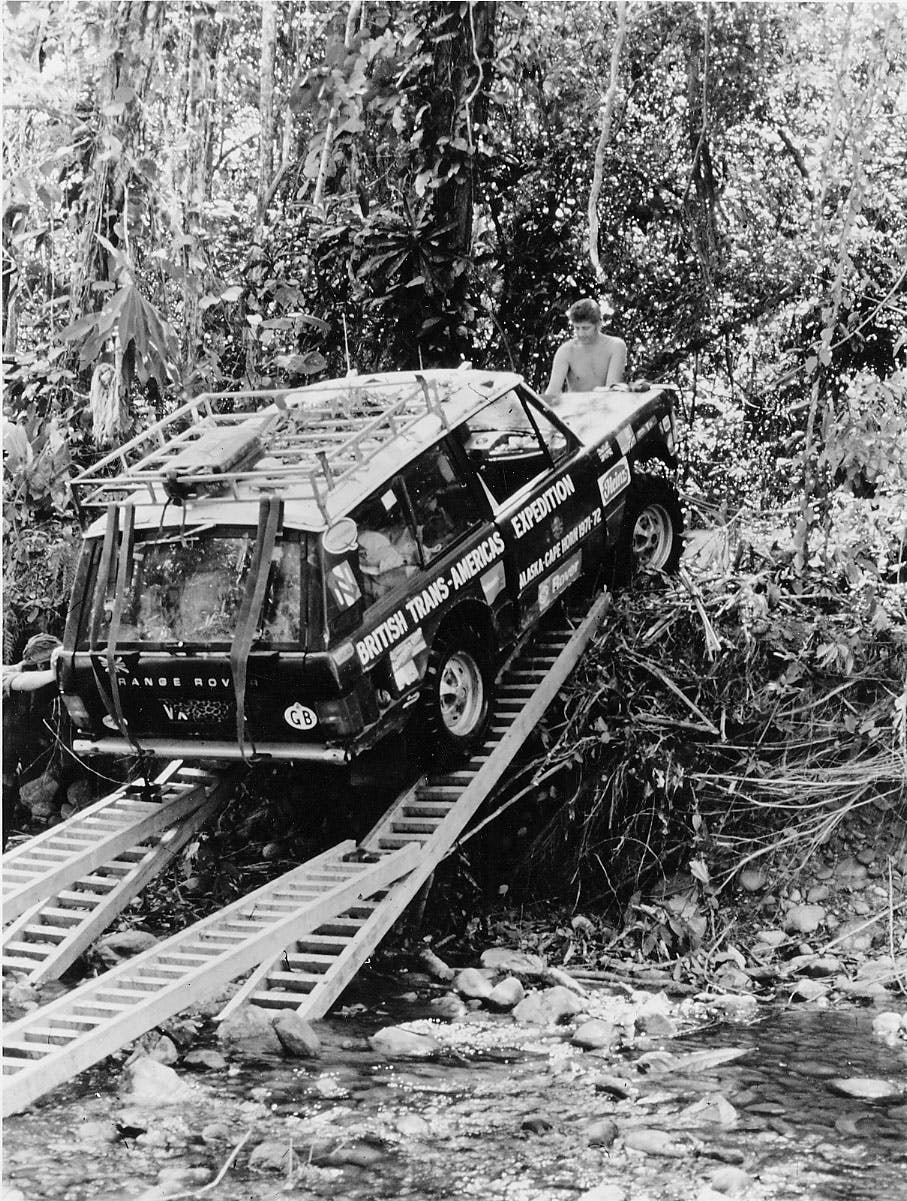

It took just over a month to claw through the snowy Canadian north on a southern trajectory, and by the time the group made it to the Gap it was nearing the end of January 1972. It was here that forward progress took on a regimented, slowed-down approach. Flanked by a team of 30 horses, men from the Trans-Americas team followed a small number of scouts into the jungle ahead, slashing and chopping a path through the trees and foliage for the Range Rovers to traverse.

The SUVs were each piloted by one man, an army officer named Gavin Thompson, who was himself under the command of Royal Engineer Bob Russell. Russell was charged with walking in front of the first vehicle as it crept its way slowly across terrain of uncertain consistency, soaked from an extended rainy season. After making it to the frontier of what had been cleared for the first Rover, Thompson would get out and run back to the second, which was guided by the carefully measured steps of another Engineer, Michael Cross.

If this sounds like the slowest possible method of traversing a treacherous jungle, you’re not wrong. Oftentimes, the Range Rovers didn’t advance more than one mile per day, with team members under assault from all manner of insects, arthropods, snakes, and bats in the process. All the while, temperatures inside the vehicles reached an astounding 140 degrees Fahrenheit.

Despite using aluminum ladder-braces to bridge the softest ground, the crew quickly discovered that the swamp tires installed on the Rovers were ineffective in the sodden Darién’s demonic mud. As they spun past the capabilities of the differentials to deal with, first the rear, then the front casings exploded, stranding both vehicles after an unsuccessful towing attempt wrought the same mechanical carnage on the would-be rescuer.

Determined, Thompson flew back to Britain to consult with colleagues. His research revealed that the swamp rubber treads had packed so much mud that, in combination with the extreme weight stacked on top of the rearmost roof rack on each vehicle, the differentials could no longer cope with the strain of the extra mass. After experimenting with overloaded Range Rovers on a simulated jungle survival course, Thompson returned to the Gap. With him came engineer Geof Miller, along with replacement sets of standard all-terrain tires and an edict to redistribute the cargo hanging off of each vehicle. New axles, too—this time with the correct lubricants installed.

Manna from heaven

The extra downtime while Thompson was away proved nevertheless productive for the Trans-Americas Expedition. By leveraging an older Series 1 Land Rover that the team picked up in Panama, the crew was able to continue trail-breaking, on some occasions using dynamite to carve a path through the thickest swampland.

Further peril awaited the repaired Range Rovers after their refurbishment. The border with Colombia and Panama presented the Pucuru heights along the Tuira River, with treacherous ravines nearly swallowing the SUVs. Several winch-outs to safety ensued. Then, there were water hazards. Although river crossings by raft were a regular feature of the voyage, at one point rough currents capsized Thompson in the middle of a channel, nearly submerging the entire vehicle. The officer escaped with his life, but he was forced to drain every fluid from the Rover after it was winched to the safety of the shore, flushing each system multiple times before successfully firing it up and continuing the drive.

Where does one find engine and transmission oil in the jungle, you might ask? The same place the Trans-Americas team procured their fuel—from the sky. In constant contact with a pair of support bases, the team would ultimately call for 15,000 gallons of gasoline and 20 tons of food and other supplies that were parachuted in by the Army Air Corps.

Seldom duplicated

In total, it took the Expedition 96 days to make its way across the Darién Gap. By June, the crew reached Tierra del Fuego, their numbers whittled down to just a half-dozen men required to handle the much less demanding, fully-charted, mostly on-road ride to Cape Horn. This leg did, of course, present new adventures, fresh challenges, and continued frustrations through Patagonia, but they paled in comparison to the Gap.

Six other groups have successfully braved the Darién in four-wheeled vehicles. Two of those included Loren Upton, who participated in a pair of aborted attempts. Upton also managed the feat on motorcycle with his wife, and he is to date the only person to drive the entire way rather than use rafts, like the Rover crew.

Today, one of the two Range Rovers that made the trip can be seen at the Dunsfold Collection, a charity museum in the south of England run as part of the U.K.’s Transport Trust. The collection is dedicated to preserving nearly 2000 significant Land Rovers and prototypes. Restored to its jungle-beating glory, the vehicle is a physical link to one of the bravest, and most challenging, automotive PR stunts of all time.

I did not take part unfortunately.. I was in the Royal Engineers and I encountered both of those mentioned. I joined as an Army apprentice in the REs.. nusually many of the officers weren’t. Gavin Thomson was a Captain in the 17/21st Lancers, and I mean this respectfully, had the most ‘plummy’ accent I have ever heard. He was an absolute gentleman as only those who are gentlemen and have nothing to prove can be. This was 1970/71? he used to bring a British Leyland Maxi which he was to crew with Prince Michael of Kent for I think the London to Mexico rally..(I should have googled before writing). Bob Russell was a corporal as part of our training regiment when I was on a course early 1973 I think. I’m no expert but as we know a main attribute of people on expeditions is to be personable, able to mix with everybody and muck in.. they both epitomised this..