Put the Haynes Motor Museum on your bucket list

Noisy, smelly, thrilling, and occasionally dangerous contrivances as they are, nothing defines an automobile more than its quality of movement. Yet motor museums, with their serried ranks of static cars seem like contrarian monuments to the ideal of petroleum-powered perambulation. These historical car parks are dotted all over the world, with their unnaturally silent and shiny exhibits, generous tax status, and legions of volunteers: the Toyota Mega Web in Tokyo; the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles; the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu (UK); the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan; the National Corvette Museum in Bowling Green, Kentucky; the Harrah Collection in Nevada; or the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart.

To that list, be sure to include the Haynes International Motor Museum in Sparkford near Yeovil in Somerset, UK. It’s huge—I know because I’m sitting in the three-year-old atrium to the multiple exhibition halls. The room is light and airy and includes a cafe capable of a mean cup of joe, the almost statutory gift shop, and a sample display of cars. One of which is a Leonardo Fioravanti-designed Ferrari 512 Berlinetta Boxer, with its massive Weber-fed, flat-12 engine sitting alongside in a cradle. “Slated unfairly by motoring journalists, who really had no idea how to drive such a powerful car,” the display alongside boldly states.

Such strong opinions stand out, especially considering those “unfair” observations came from some of the finest motoring writers (and road testers) of their generation. Perhaps these are the trenchant views of John Haynes OBE, founder and trust chairman to this eponymous museum, publisher of the hugely successful series of Haynes Manuals, and talented race driver?

Matt Piper, curator of the museum, blushes slightly and avoids the question when I ask who wrote this sign board, though he’s on firmer ground when I ask about this museum. It was founded in July 1985 and originally based around John Haynes’s personal collection of approximately 35 vehicles. “It’s grown through a process of acquisition, donation, and purchase,” he says. “It’s a charity, but it has independent status. We support ourselves.”

Like virtually all museums, the Haynes International Motor Museum’s charitable status is officially recognized and allows exemption from most taxes, but imposes strictly defined responsibilities for education, training, and conservation—a party of school children is noisily clattering into the museum as we speak.

The museum has 50 permanent staff and 60 volunteers. There are more than 300 exhibits and, along with the gift shop, there are also a number of commercial extensions which help to support the charity. That includes extraordinarily popular conference facilities, a wedding catering business where couples can celebrate their nuptials around the cars, and also an independent garage and body shop that works on the museum’s cars as well as those of customers. When we visited the workshop, it was servicing a charming mix of modern and old motor cars.

In addition, there are events throughout the year, lectures on a wide variety of subjects, and themed breakfast-club meetings, when owners and enthusiasts meet over bacon sandwiches (or “bacon butty,” in British English). Next year’s themes include Land Rover, Jaguar, American, and Italian Power.

Each year the Haynes Museum receives more than 100,000 visitors, small beer compared to the 1.8 million visitors to the Henry Ford Museum and its four sister blue-oval attractions, but small doesn’t necessarily mean diminished. There’s an absence of ropes, warnings, and alarms here. Children are encouraged to get up close, and they can also engage in a series of brass rubbings from plaques dotted around the hall.

Our first stop, almost by accident, is “The Red Room,” which is possibly the most eclectic display of motor cars you could encounter. This rangy collection of sports and GT cars takes in Alfa Romeos, Triumphs, ACs, Chevys, even a Rochdale Olympic—all beautifully kept, largely original, and irredeemably scarlet. Red is so overwhelming and disguises the cars so effectively that you are forced to walk each aisle to identify each model.

The museum’s collection includes a foundation block of automotive history, a display on what is surely the world’s first driving offense by Bertha Benz (née Ringer), wife and business partner of Karl Benz. In August 1888, Bertha and her two sons drove the 66 miles between Mannheim and Pforzheim without permission from Karl or the authorities, and in doing so achieved first-ever accolades for distance driving and auto theft. This touching display sits alongside the museum’s 1898 Daimler Wagonette, owned and photographed locally as a wedding car, with almost every one of the guests in the old sepia photo painstakingly identified by the museum.

“We take our cars so much for granted these days, but at one time you had to be incredibly wealthy to own one,” Piper says. “And it’s the social history [of the car] that is almost as fascinating. With cars you enter your own little world of friends and family, and it’s almost as important to hear those stories of what those cars mean to us.”

I ask Piper, do the cars run? “We maintain some in working order, but not all,” he says, pointing out the costs of having every car in the museum road-ready would be prohibitive. “Last year we had 50 cars running to celebrate our ‘In Motion’ display; it’s about the sound, it’s about the smell.”

Piper and I wander from hall to hall, moaning about the high value of classics these days, which pushes up the insurance and maintenance costs for the museum. He’s a diligent curator—knowledgeable, witty, and with a sense of pride, which means we stop frequently while he straightens a sign board or picks up tiny pieces of litter. We pass a small but well-selected Ferrari display, and then enter a long and lovely hall known as ‘Memory Lane,’ which might just as easily be called ‘My Dad Had One Of Those,’ followed by some smashing rally cars and racing saloons in motorsport section. “We’re looking at the changes that are taking place in modern motorsport and how we might adapt our displays to interpret that,” Piper says.

As well as a charming display of small scooters (it’s a European thing), the museum has a well-curated collection of old motorcycles, which sits near a brilliant special exhibit devoted to Mark Webber, Formula 1 and Endurance racing ace, with one of his Red Bull F1 racers. It’s accompanied by a series of large-screen displays, where one of the most approachable and thoughtful racing drivers talks quite intimately about his career’s highs and lows.

“I shouldn’t really have favourites,” Piper says. “All our exhibits are equal, but some are more so than others.” He gestures at a starry display in the ‘American Dream’ hall, where Derham-bodied 1931 Duesenberg Model J stands in the center of a chevron flanked by a Cord and an Auburn, the trio all related through the genius of designer Gordon Buehrig.

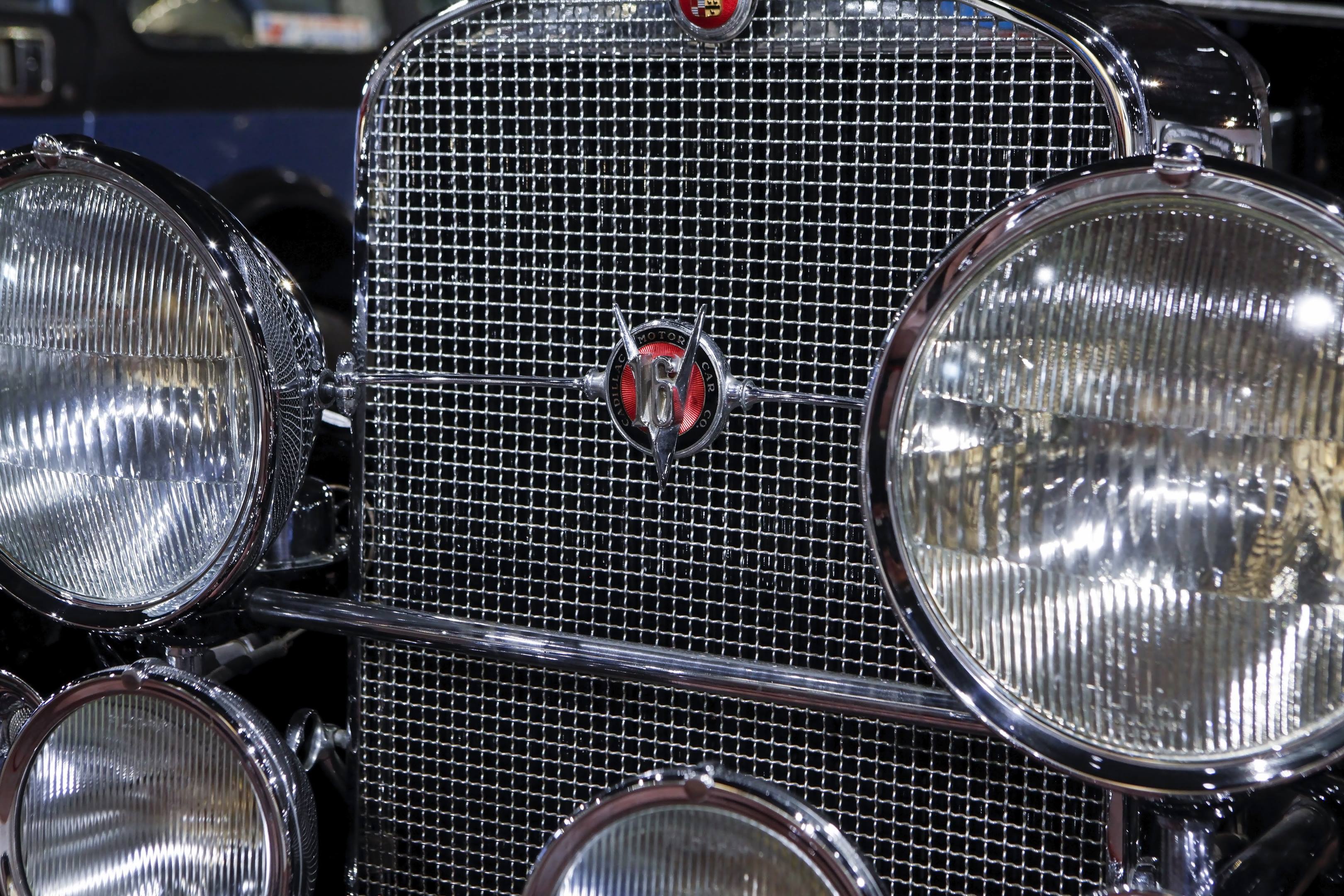

Piper explains that this Duesenberg belonged to Dorothy Elmhirst (neé Whitney), but examples of the claimed ‘World’s Finest Motor Car’ were driven by Greta Garbo, Howard Hughes, William Randolf Hearst, Tyrone Power, and even Al Capone. This opulent display even over shadows the Cadillac V-16 standing close by, although Piper says he has a soft spot for the huge ’30s Caddy, mainly because of its embodiment of engine development of the time.

“You asked about what our purpose is, and the motor car is one of those inventions that has changed the world, for better and worse,” Piper says. “We try to show that—how it’s made the world smaller and changed lives. We’re passionate about what we do; this is industrial design which has meant an awful lot to people. What we do might not be the fount of all automotive knowledge, but we do teach, and if someone—even knowledgeable—learns or sees something they haven’t before, then I feel quite chuffed.”

We walk slowly towards the exit; I hadn’t noticed we’ve been here more than two hours and barely stopped. Coming out of the exhibition halls, through a celebration of Alex Issigonis’s Mini, Piper asks me what I think is the rarest car in museum. I mutter something about the Duesenberg, or the Cord, and he points upward. Slung under a parachute above us, befitting its military air-portable aspirations, is a super-rare prototype for the Mini Moke. It was rejected by the forces to which it was aimed but found a new life as a strictly on-the-road beach buggy. The best museums always have surprises. By that, and any other measure, the Haynes Museum ranks among the top tier or motoring exhibits on the planet.