What Watches, Art, and Handbags Illuminate about a Cooling Car Market

As we observed in our most recent Hagerty Market Rating, the collector car market is cooling, and has been for the last 19 months. That said, it’s important to look at the larger story: The collector car market, measured by this rating, is still stronger than it was before the unprecedented gains of the pandemic years. In 2022, during that boom, we took a look around at the markets for other collectibles—fine art, NFTs, and sneakers—to see what we could learn. Perhaps to no one’s surprise, collector markets of all stripes took off in that era. Two years later, as the cooling classic-car market continues to search for equilibrium, we decided to repeat the check-in, to see whether other collector segments are slowing in the same fashion. This time, however, we looked at different luxury goods.

Like collector cars, which you would own in addition to your daily transportation, the other three collectibles we chose here are nice-to-haves, not need-to-haves: Fine art (again—its maturity as a market makes it a perennially valuable comparison), watches, and handbags (the high-end, carefully crafted kind). Like cars, all three are collected globally, and thus influenced by geopolitical tensions and large-scale economic trends: Think inflation in the U.S., war in Eastern Europe, the Chinese economy struggling to recover from strict COVID policies, etc.

There are a few important differences between the four markets, starting with demographics. Though the age ranges for watch and handbag collectors are similarly broad—20 to 80 for the former, 30 to 70 for the latter—the watch market, like the classic-car market, is dominated by men. The market for handbags is largely composed of women. Fine art hosts a mix of both. While the price of the most expensive painting (Salvatore Mundi, by Leonardo da Vinci, $450M) dwarfs that of the most expensive car ($142M, Mercedes-Benz Uhlenhaut Coupe) and watch (a $31.2M Patek Phillipe), the watch market (including retail) is larger than the art market, measured in value: $74.6B to $65B. At $513,200, the most expensive handbag sold at auction (a crocodile Hermès Kelly 28 Himalaya with diamond-encrusted hardware) falls well below the most expensive examples of fine art, cars, or watches (in that order), but the handbag market is also far younger than any of the other three: Its rise is closely connected to the rise of the Internet, in the late ‘90s.

The tl;dr is that post-pandemic cooling is not restricted to the collector car market. Naturally, we dug deeper, and were rewarded: Each field revealed similar trends in buying behavior, as well as increasing interest from younger collectors. Whether the treasure of your collection is a Birkin or a Bugatti, we are confident that you will gain a richer understanding of collecting from what these experts have to say. We certainly did.

Volatility of Novelty

Everything got hot during COVID, but some less-established names got really hot, really quickly. The inverse is occurring now: The most dramatic decreases in the last few years are confined to those superheated segments that, in hindsight, were most due for a correction. Let’s start with the collector vehicle market, specifically with trucks and SUVs from the late 1970s and ’80s. Ford Broncos, Chevrolet Blazers, and Land Rover Defenders from this era were hot even before 2020. In 2017 and 2018, the average appreciation for this set was 26%. From 2019 to 2022, that figure spiked to 91%. The bubble has let some air out. In the last two years, the average change for these vehicles is -7%. A significant change in trajectory, yes, but it didn’t erase COVID-era gains.

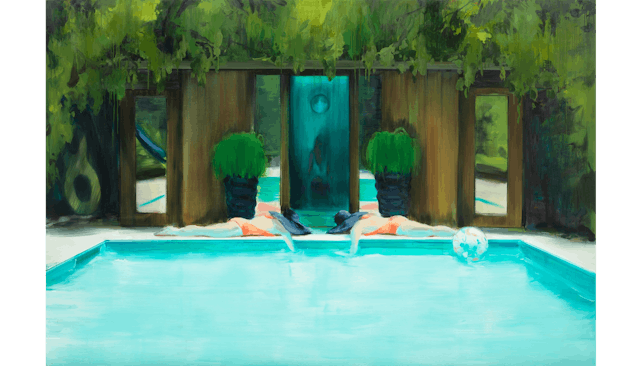

In the world of fine art, young contemporary artists (under 45) “overheated dramatically in 2022” according to The Fine Art Group’s 2023–2024 Global Art Market Report. Sales doubled, the report says, in 2021, compared to 2019 and 2020, only to correct, equally dramatically, in 2023, when they reverted to pre-pandemic levels. “It’s important and needs to happen,” says Anita Heriot, president of The Fine Art Group. She diagnoses the segment as “overheated,” adding that there simply is “not enough track record for the [young contemporary] artist to really consider them investment-quality.”

In the world of timepieces, the parallel is “hype watches,” typically stainless-steel versions of pieces that are coveted from the moment they are produced and, because of that desirability, easy to flip for far above retail price. The trio, according to Hodinkee, are the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, the Patek Philippe Nautilus, and the Rolex Daytona. Tiffany To, head of sales for Phillips’ watch department, calls out a stainless-steel variant of Daytona called the Panda, which retails for $10,000. “At its height, it went up to $40,000,” she says. “Now it’s in the middle ground at around maybe $30,000. It’s still triple the retail price, but it’s just not at a level where it was completely nuts as it was two years ago.” She sees the trajectory as a natural correction: “The more people bought [a stainless-steel Daytona], the more other people thought it was an investment and then everyone kept trying to jump onto the bandwagon until at some point it just wasn’t sustainable anymore and it just flopped.”

When we spoke with Max Brownawell, head of Christie’s handbag and accessories department, he painted a less dramatic picture. Handbags overall increased in value by about 25% during the pandemic. As we saw in the car market, the examples at the top of the handbag market set records: In November of 2020, Christie’s set a new world record for the most expensive bag sold, a 25-centimeter Hermès Kelly that brought $435,375. The auction house broke its own record a year later with another Kelly 28 Himalaya, one with diamond-encrusted hardware that brought $513,200. Today, Max says, those prices are very difficult to achieve. Prices for bags at the top of the market have come down, while prices for more accessible bags and leather bags have continued to rise. (Another pattern we’ve observed in classic cars, as borne out by our Blue Chip and Affordable Cars indexes.) Though annual increases in value are still going up, the pace of that growth has slowed, and increases are in the single digits.

As with the Bronco, Blazer, and their ilk, young contemporary artists and stainless-steel Rolex Daytonas are still bona fide collectibles. Corrections haven’t erased their gains, and even though their performance has been volatile, it’s an oversimplification to say that anyone who has invested heavily in one of those superheated segments is out in the cold. Some works by young contemporary artists, too, have not only survived the correction but are now thriving. The Fine Art Group points out Caroline Walker, a Scottish artist, who had the good fortune to be shown in museums before the pandemic. That foundation is helping protect her against the volatility of her genre.

Demographic Changes

When it comes to demographics within the four markets, each of the experts we discussed painted an optimistic picture: Younger buyers are entering the market. In the case of watches, however, the tastes of those buyers are influenced by a highly unpredictable factor: social media. “It has a life of its own,” says Tiffany To. Younger buyers, says vintage watch dealer Eric Wind, aren’t always interested in the same things as older buyers; they are more likely to be influenced by trends, fashion, and what (and who) they see on social media. To points to the collaboration between Audemars Piguet and Houston-based rapper Travis Scott: “Once everyone on Instagram saw him wearing the watch, people wanted the model, it became super hot.” Brownawell says that the handbag market reflects a similar influx of younger buyers—Gen Z in particular—and an influence from social media, which drives demand for certain colors or styles.

Demographic changes in the classic car market don’t reflect anything dramatic over the last four to five years (before, during, and after the pandemic): Our insurance quote data reveals a changing of the guard supported by a gradual upswell of younger interest. Gen X is now the largest generation, surpassing that of the baby boomer for the first time in the number of quotes. Of the younger generations, millennials are increasing slowly and steadily. Gen Z surpassed preboomers back in the spring of 2021, and their share of quote data has only gotten larger since.

Changing Tastes

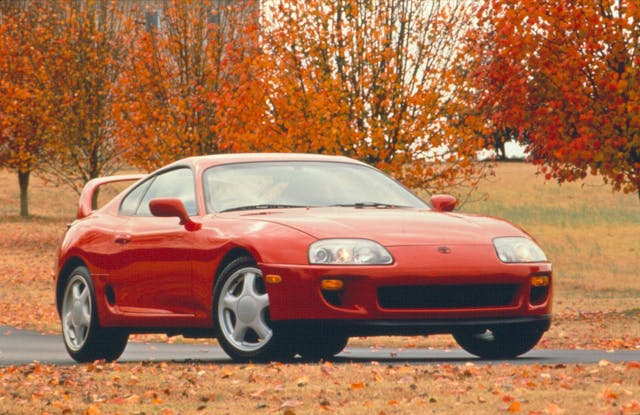

Nostalgia plays a major factor in the markets for cars and for watches, and what is nostalgic is determined by the age group most dominant in that market. “I think of it as generational collecting,” says To. “You see resurgence of each period pending on the profile of the people who have purchasing power today.” Think of the rise of Gen X in the collector-car market, and the concurrent appreciation of ‘80s and ‘90s, or Radwood-era cars. The pattern also explains why certain items fall out of fashion: “People don’t really buy pocketwatches today because people who are 40 or 50 didn’t dream of pocketwatches as children. That era passed.”

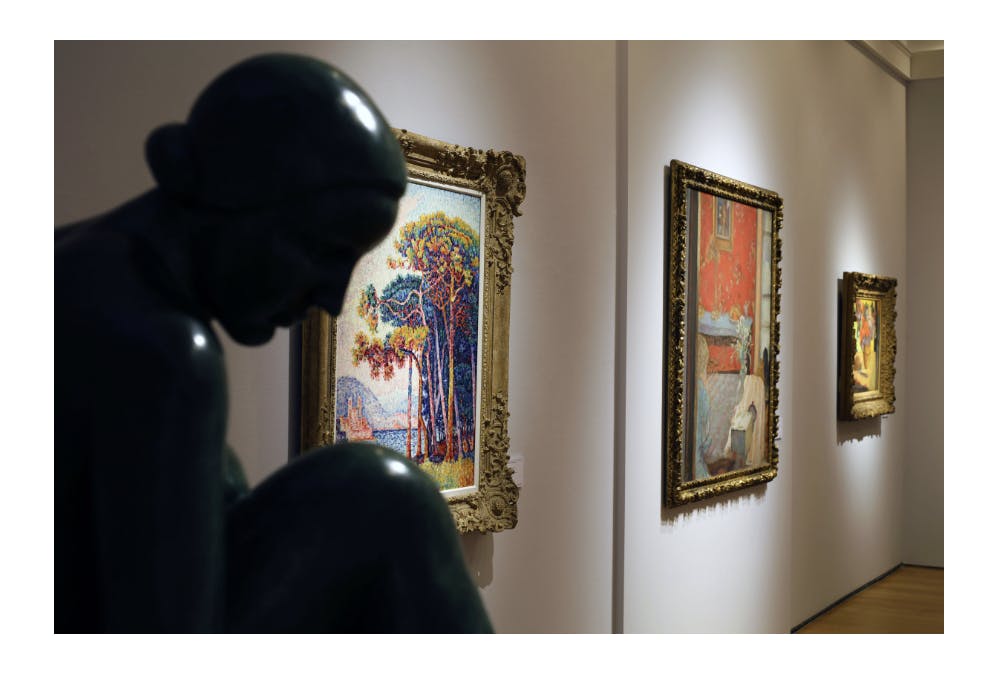

Relevance and collectability don’t directly correlate, however. Just look at the $94.4M sale by Sotheby’s of Gustav Klimt’s Dame mit Fächer (Lady with a Fan) last year. An Impressionist work, it was the highest-value picture ever sold at auction on the European continent. “Everyone says that impressionism (in fine art) is hard to sell … it’s an older person thing.” But, as a $12.1M Mercedes Simplex proved at the 2024 Amelia Island auctions, a work can still make millions if it is the best representation of its era. Not only was the Simplex the most expensive result from those auctions, it was the most expensive by a factor of nearly three.

Desirability of Originality

Cars, handbags, and watches all have something in common: New ones are being produced all the time, which means that if you want something that no one else has—a sentiment shared by more serious collectors—you’re going to look at secondary markets. There, certain types of imperfection are actually desired, not only because of attrition and the rarity of well-preserved examples, but also because imperfections can tell a particular story that makes an item unique. “The Japanese call it wabi sabi,” says Wind. “It’s what gives [a watch] character.” If that story involves a celebrity, or an important event, all the better. Often, originality or authenticity itself is what collectors prize. Take a closer look at that Simplex mentioned above. Note the peeling paint and weathered upholstery.

Patterns of stratification in each of the markets bear out the desirability of originality. Says To of watches: “A collector would rather have a watch that is highly worn, but showing all its original definitions on the side of the case, rather than sending it to the factory and coming up brand new with today’s parts. Wind adds a specific example: “There’s a huge difference between, say, a 1950s, small-crown Submariner that has a service-replacement dial, and bezels, bracelets, et cetera—that might be an $8000 watch—but an original example could be $500,000 at auction.”

The handbag market appears to be following the same trend that our own Dave Kinney, publisher of the Hagerty Price Guide, observed in the car market: Serious buyers are getting more selective. The value of an example isn’t captured solely by its configuration or condition. To be desirable, the example must also have the right paperwork and provenance. As Max Brownawell observes about the handbag market, buyers are increasingly looking for a bag to be accompanied by its original box, accessories, receipt, and/or factory paperwork. All three markets understand the value of a factory-spec restoration—the handbag market is especially picky, requiring the work to be done by the manufacturer—and prove the truth that Kinney captures: “Restored is OK, but original is better, and sometimes way better.”

Long-Tail COVID Changes

The COVID era introduced speculation and volatility, but to reduce the last four or five years to that story risks oversimplification, as does a conviction that 2023’s cooling is a cause for major concern. When we interviewed experts in the collector car market at the end of 2023, the consensus was a decelerating but stable market. The Hagerty Market Rating, at 65.41 as of April 19, may be on the longest unbroken losing streak in its history, but it remains safely above the 50 of a flat market and higher than any point in the four years leading up to its most recent surge.

The art market finished 2023 with a global total of $5.74B in sales, a 27% drop from 2021, according to The Fine Art Group’s year-end report. As drastic as that sounds, the latest non-COVID-related highwater mark was 2018, whose total of $12.33B was heavily swayed by one Christie’s sale ($835M for The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller) and, with that discount, 2023 ended only 9% below 2018. The Art Group concludes by calling 2023 “a natural and necessary decline from a period of unprecedented and unsustainable price points.”

The handbag market, on the other hand, appears to be sitting pretty: Between 2019 and 2023, says Christie’s Brownawell, the Handbags & Accessories auction market grew by 28% overall. Christie’s own department, which comprised 52% of the global handbag market in 2023, observed 94% sell-through rates; far stronger than the art market or the classic-car auction market (live and online), whose numbers are both declining.

One thing is sure: Online auctions, forced centerstage by COVID, are here to stay, no matter which of the four luxury goods we’re discussing. Heriot says that COVID was the single biggest factor in increasing the popularity (by 400% or more) of online auctions for art, a notoriously “persnickety” market that can punish an “overexposed” lot. From 2019 to 2023, total sales of online collector-car auctions ballooned from $243.74M to $1.7B. Online participation in Phillips watch auctions doubled or tripled in the last few years, To says. Post-COVID, Christie’s only hosts one live handbag auction, in Hong Kong, and not because online is weak: The local market in Hong Kong is particularly strong, and export restrictions around alligator and crocodile bags artificially localize the market.

What’s not as clear is what sort of a factor social media is in the market. Gen Z, the group whose youngest years were dominated by social media, has yet to age into its prime earning years. Will the transience of online trends become so obvious that even younger collectors brush it off? Or will it become a new factor in taste-making for a rising generation?

A Few Takeaways

Some things, of course, never changed. One is that the serious collectors have patience and crave the best, not simply the most popular. “When you’re starting to collect,” says To, “you want the thing that’s most recognizable. Once you’ve collected all these highly recognizable pieces, then I would say people become more nuanced. They want to go deeper.” Often, this desire prompts a turn from the retail to the secondary market. Wind identifies a complementary motivator: the desire for something more exclusive, more individual. “I would say more people in the kind of fashion world, athletes, [people] who would never think about vintage watches—actors, musicians as well—all these demographics were sort of more focused on modern watches traditionally.” As with cars or handbags, the finite selection within the vintage market offers more exclusivity than the retail market, in which there might be thousands of a single reference, and that limited selection offers more of a challenge to those who want the best. To, again: “The game is not just paying as much as you can, but it’s having the patience to search, hunt for certain references.” Money, of course, cannot always prize the piece that you want out of the hands of another buyer … and that hunt, and that game, is what attracts such passion-driven buyers.

Such patience may or may not be accompanied by curation of your collection as a collection; you may simply buy what you like. As Brownawell says, “There’s a big element of our buyers that I would call shoppers, more than collectors … They’re not necessarily looking at their [handbag] collection as something that they’re developing over time. It’s just something that they do. This is just what they buy.” If you nodded as you read that sentiment, you likely buy out of genuine love for the object, regardless of whether others recognize a car, bag, or piece of art as a statement about your taste or status.

Nearly everyone we interviewed for this piece attested to another lasting truth: the value of education. “I’ve seen people blow, in some cases, millions of dollars buying things that they shouldn’t have, you know, either overpriced or misrepresented Frankenstein watches, et cetera,” says Wind. “It’s a huge negative for the market because those people leave the field forever typically.” The more educated collectors are, he says, the happier they will be and the stronger the market will become. At Hagerty we have a similar goal: We want to celebrate vintage cars, educate younger buyers about their quirks, and empower them to make informed decisions not only about purchase but about maintenance.

It’s not just individual dealers or publications that take on this responsibility; auction houses accept the mantle, too. As Brownawell says, “When we get a very rare vintage piece that might not be appreciated by the larger collecting community, that’s our opportunity to teach people about it and to increase the level of scholarship within the market and introduce it to a large audience.” Much of the education, too, happens between collectors, no matter whether you’re discussing how to jet a carburetor or the best insert to protect the lining of your Birkin.

If you are genuinely passionate about bags, watches, cars, or art, buy what you love, learn about it, and seek out the community around it: You might even come out ahead. Despite the unprecedented heating earlier in the decade, it’s clear that collector markets are generally correcting. (The handbag market is riding higher than the other three, which may be tied to its relative youth; time will tell.) New buyers are entering the market, and new eras, varieties, brands, and manufacturers are finding their footing. This sort of growth, while it may contribute to instability, is what keeps every collector market humming, and if the last few years are any indication, the market always recovers.

Back in the day I had a buddy that repaired high end watches. He was a trained instrument repairman from the Air Force. He would buy high end watches and sell them to fund his cars.

Today I have two co workers buying and selling watches for what I used to pay for cars.

I stopped wearing watches years ago. I have two collecting dust somewhere. I figure I always have the time on me anywhere I go. Not really into hand bags since I’m a guy but even my wife would never pay the crazy money some people pay for them.

As a side note that last pic with the Supra might be one of the few “clip art” pictures for that car. Usually when someone wants to find a picture of a Supra they pull this one out of the limited collection there is unless they take their own.

Never really wore a watch as with working on cars it was always in the way.

I have owned three Rolex watches. Superlative Chronometer, my *ss. All three lost about one minute every 3-4 days. I have a “Pepsi Bezel” GMT Master that I purchased new in 1979 for $890. It is worth stupid money today, comparatively. Their cost today is such that I would never purchase one new (or used!) again.

Rolex is the most recognized name in watches. They’re ‘ the watch ‘ that most men who feel the need to buy a somewhat higher end (10-11k) timepiece choose. The Oyster Perpetual and the Daytona ‘Panda’ as shown. While they’re not bad watches many are purchased only because they’re the name that’s known and no other. If you asked the typical owner if they considered a TAG they might recognize the name. If you were to say an IWC probably not. There isn’t a Rolex on my top ten wish list although there are a number of other watches that actually cost less. For those of us who wear them you’ll wear a different style watch for different occasions.If you’re just going camping throw on the Timex Explorer. The ‘Indiglow’ feature is great when your sitting around the campfire and someone asks the time. -J+S – Automatics are like cars, they need to be run. If left sitting they’ll loose time. If you bought it second hand and they had been left in a drawer it will most certainly need a good cleaning. And if you don’t trust Rolex don’t buy a Tudor. I’ve bought a few really nice older automatics at garage sales that hadn’t seen the light of day in years for little money. – “Take the fifteen bucks honey. It’s not like it’s a Rolex and you never wear it anyway.”

ps- I sometimes wear a watch on each wrist ( usually contrary in style ). Then I saw an old interview with Peter O’Toole who did likewise. _ ” Why do you wear two watches?” _ ” So I don’t waste time looking at the wrong hand.”