Piston Slap: Trust Your Eyes at Your Own Risk

Adam writes:

Sajeev,

Thank you for your response (regarding the need for repair manuals)! I followed your directions exactly and also reviewed the newly arrived shop manual, and everything looked up to snuff. I checked the door wiring and also around the pedal assembly and couldn’t see any chafing, etc. and no wiggling of the wires in those areas—seemed to all check out fine. Meanwhile, at the same time, I also had an issue with the 4WD transfer case motor. The motor was binding, and sometimes it would go into 4WD and sometimes it would not, and it would rarely illuminate the 4WD light on the dash.

I took it to the dealer to have them look at the transfer case, as I wasn’t sure if it was an internal failure of the case, the transfer case motor, the switch, or relay. The dealership called and said it was the transfer case motor, so I told them to replace it. When I went to pay for it, they said:

“Oh, we noticed your power mirrors were not working. We checked and the fuse was blown, so we replaced it and its working normally now.”

I explained to them the trouble I’ve been having with the fuse and they said, “Well, it worked fine for us—we road tested the vehicle, ran all the power accessories, and it still works fine.” I’ve checked it daily since I got it back and the mirrors are still working. Although I do doubt my ability to replace a fuse, and doubt that I bought a batch of bad fuses. I’m going to try not to obsess about it. It did force me to spend the money on the shop manual while I could still get one cheaply. So it’s a win in that way. Thank you again for your help!

Sajeev concludes:

I am glad I could help … sort of? Armchair quarterbacking is a pitfall of this series, but I’d like to think this was a learning experience for many of us.

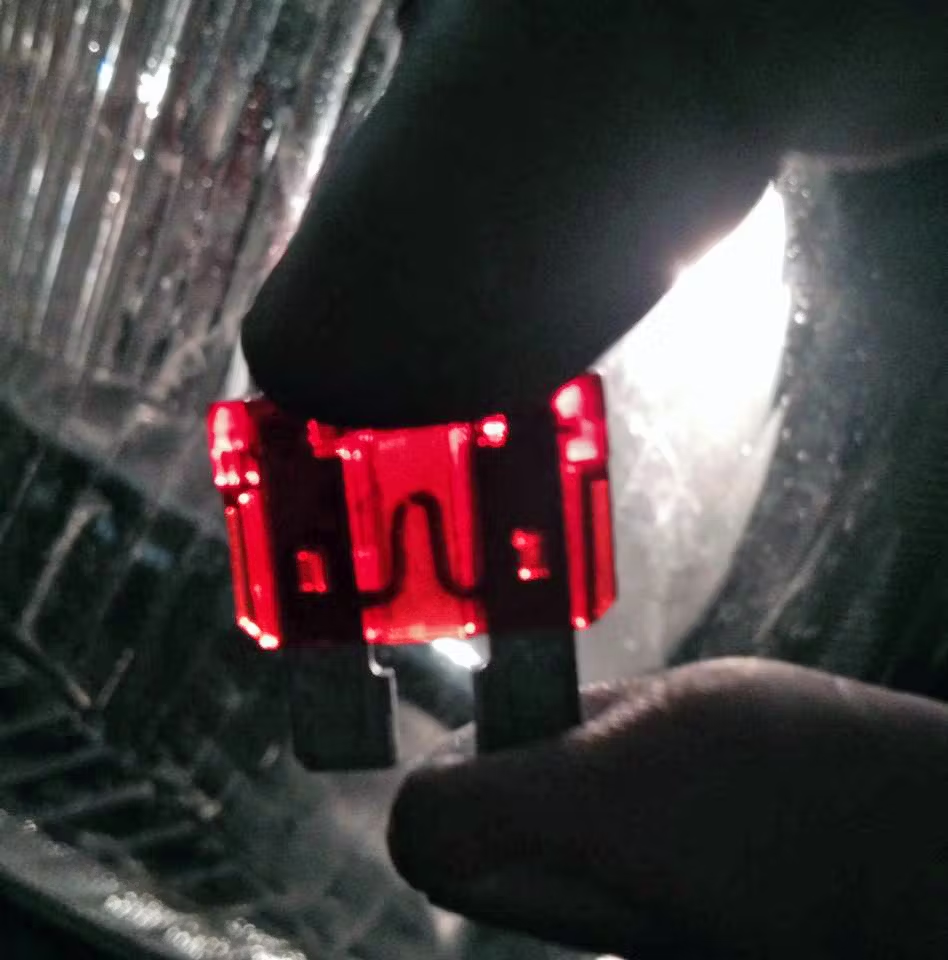

Your quandary points to something I learned years ago, something we tend to ignore: Our eyes often lie to us. Be it a match on a dating app or a fuse with a hairline fracture, the reality of the situation might not be accurately reflected in what’s before our eyes.

The fractured fuse above became my problem about 11 years ago. It took out the headlights of my UK-import Ford Sierra, but the untrained eye believed it still had a good fuse. Luckily, the Sierra is a famously easy-to-service vehicle, so I pulled the wiring harness at the headlight and tested for voltage. When I found no voltage, I replaced the fuse. Care to guess what happened?

We should do ourselves a favor and only test fuses with a multimeter and the exposed metal bits (video above) present in all (most?) fuses when installed in a fusebox. We may not always have a multimeter, but if one is handy, do not remove them and trust your eyeballs for an accurate decision.

What say you, Hagerty Community? Yank and look, or test with the proper tool?

Have a question you’d like answered on Piston Slap? Send your queries to pistonslap@hagerty.com—give us as much detail as possible so we can help! Keep in mind this is a weekly column, so if you need an expedited answer, please tell me in your email.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Test with an incandescent test light is preferred. It puts some load on the circuit and the relative brightness gives a much better indication of the fuse’s integrity than an LED test light or a modern DMM which draws so little current that it can give a false positive. It is also easier than using a DMM because the light is going to be where you are looking to poke the probe rather than someplace else.

I agree. I always test with an old-style “bulb test probe” before using any other test device. Like Scoutdude says, the brightness of the bulb can tell you more than just “is the circuit closed”. And since my old eyes required glasses even when younger, I very seldom rely on them to analyze the serviceability of a fuse.

Absolutely – my first thought. I try to test from terminal to terminal, rather that the fuse itself, when reachable. That way you may find light corrosion on the fuse contact, so resistance can vary. And when space permits, wire a sealed-beam headlight bulb to a set of probes.

There are other possibilities… the fault is intermittent, or you inadvertently corrected (sort of) the fault when you tugged around on wires

That gap on a fuse can be so hard to see depending on how it goes. At least the problem got solved.

Fuse breaks are much easier to spot–and much more prevalent–on the old cartridge fuses used on German cars of the 50s through 70s. And the do wear out…