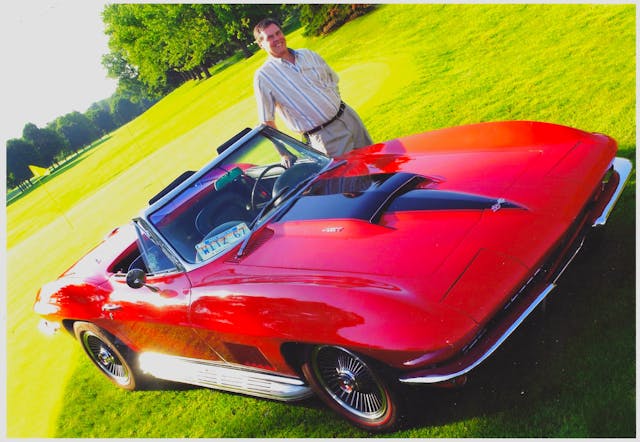

My “Big Block” Corvette Got Me Back into Old Cars

Say you just bought a fine-looking, Rally Red 1967 Corvette convertible. Naturally, you take it to a car show. As you’re backing into your assigned spot, a number of people gather around. You shut down the engine, and the bystanders ask you to open the hood of the Vette.

Then it dawns on you why they are anxious to see the engine. The “stinger” hood of your Corvette says the engine beneath it is a big-block 427. Your car’s exhaust note says otherwise. The attendees see the car—and you—as a fraud. And they are correct: Your Corvette’s engine is a slightly hopped-up small-block 327, but a previous owner bolted on that super-cool stinger hood and “off-road” side pipes. The car sure looks like a 427, but it is, in fact, a faux big-block … which is why you got the car for an affordable price.

This was me the first time—and every time after that—I entered my newly acquired ’67 ‘Vette in a collector-car show. I loved the look of that stinger hood but was uncomfortable with the unintended deception. I would jump out, pop the hood, and explain that it had been installed by a previous owner. I wasn’t trying to fool anyone … as if I could. That small-block ran well and sounded good—but it didn’t sound like a muscular big-block. Show-goers would nod, not saying much, and walk away, pleased to have detected and exposed fraud on the show field. Corvette collectors, I soon learned, take authenticity very seriously. As they should.

At that stage of my life, I thought I was done with the old-car hobby. I hadn’t owned an old car since the gorgeous ’67 Cadillac Eldorado I had for a while in the late ‘70s and the beautiful ’70 1/2 Chevy Camaro I had bought new, kept, and driven aggressively until I got married in 1982 and moved to California, with its high home prices (both good stories for other times). I had no more time, money, or energy for old cars and had grown tired of maintaining and working on them.

That ’67 was my second Corvette after the well-used ’57 I drove during my senior year in high school (another good story). As a busy auto writer and part-time racer, I reviewed new Corvettes and enjoyed more than a few adventures road-racing them. I sure didn’t need to own a Corvette, especially an old one.

In 1998, I founded a car show at Michigan State University that evolved the following year into the “Cars on Campus” (COC) invitational concours d’elegance. I attended shows all over Michigan looking for cars to invite to the growing event. After recruiting for most of the summer, I decided that talking to proud collector-car owners and inviting them to show their special cars at our event would be easier if I were an entrant rather than simply a spectator.

I started looking for a good collector car, and I found this relatively low-mileage, fairly good-condition ’67 (alleged) 427 ‘Vette roadster in the “For Sale” lot at a big show at the old Packard Proving Grounds in Shelby Township, Michigan. (The C2 has always been my favorite old Corvette and, for multiple reasons, the five-gill ’67 my favorite C2.)

I got the owner’s contact info and hurried home to discuss the purchase with my wife Jill, a long-time Corvette lover who happened to have a 2000 C5 convertible, wearing Michigan State University green, in our garage at the time. I was hoping she would go with me to take a good look at and drive the ’67, and, if we decided to buy it, agree to split the price and co-own the car. And she did! I can’t recall or locate any record of how much we paid for that car in June 2000, but I think it was something under $30K.

We joined the Michigan chapter of a national Corvette club and drove the ’67 up to one of the club’s events in Traverse City. While there, we enjoyed a rocking George Thorogood & the Destroyers concert at a hotel/casino and each happily pocketed the $20 the casino gave us to gamble. (We figured that driving a newly acquired 33-year-old Corvette there and back would be enough of a thrill.)

The Corvette performed well but showed some rough edges along the way. For starters, it was annoyingly noisy at freeway speeds. Yes, it was delicious, small-block, side-exhaust-V-8 noise, but the volume got old after a while. Water leaked into the cabin between the top and windshield when we encountered rain, and we had to manually pop up the headlamps at night. The brakes were barely there, the manual steering built some muscle, the window cranks were clunky, and the four-speed manual shifter was loose and cranky. At least the vertically mounted aftermarket AM/FM radio I had installed—with great difficulty—to replace the dysfunctional original unit worked fine!

Though she loves Corvettes, Jill quickly lost interest in driving the ’67. I took it to some other shows, including Cars on Campus at Michigan State, where I would park it, then busy myself running the event, thus avoiding the need to explain its faux 427 status. I decided to get its many flaws attended to by fellow journalist and friend Don Sherman. He had just restored his own (real) big-block ’67, a former drag car, and had written an excellent book about it, and he had volunteered to fix everything he could on ours for a reasonable hourly rate. I purchased a set of spiffy, cast-aluminum wheels that looked like the ’67 optional originals, along with replica redline radial tires to greatly improve the car’s look, ride, and handling, and delivered the car to Sherman’s house.

Don proved to be as good a Corvette mechanic as he was a writer. It’s too much detail to recount here, but he provided a running record of everything he did, from fixing the backup light, the pop-up-headlamps, and the door latches to adjusting the parking brake, steering, and shift linkages to installing my new wheels and tires and a new fuel tank (the original leaked), refurbishing the inside door panels, and resealing the engine oil pan to resolve some minor oil leakage.

Sherman also discovered that the car had some repaired crash damage on the driver’s side, and he communicated with the guy we bought it from to research its non-stock engine. It turned out that the car had been built with the base, 300-hp 327, but a previous owner had installed valve covers, an intake manifold, a higher-redline tach, and maybe a camshaft from an optional 350-hp engine, plus an aftermarket reproduction Edelbrock carburetor, to make it look like an L29 350. Happily, Don found that the engine block was original and its insides “fastidiously clean.”

The following May, ace auction announcer, historic car appraiser, and friend Ed Lucas, “after thoroughly examining this restored automobile and subsequently researching the information provided,” estimated our ’67 Corvette’s replacement value between $42,500 and $45,000. “It is obvious from inspecting this vehicle that it has received excellent care and maintenance and is in overall very good condition with low total mileage,” he wrote in his appraisal. “There is little or no evidence of wear or abuse.”

“Overall,” the report concluded, “the engine compartment is very clean, the exterior chrome and paint are in very good condition, and there is no evidence of underside rust… In fact, the undercarriage has been detailed… As a final point, it should be considered that this is a numbers-matching vehicle showing only 38,680 miles on the odometer.”

By then, “Cars on Campus” Concours had grown (with a great deal of work) into a very nice 200-car show on a field next to the president’s house on MSU’s beautiful campus. The event ended after 2002 when the university wanted more money and reduced its support. I was keeping the ’67 in a farmer’s barn (along with my 1991 Buick Reatta ragtop, another good story) a few miles from our home and took it out only occasionally.

One of those occasions each year was the “Rolling Sculpture” car show in downtown Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Sherman (who worked there for Automobile magazine at the time) saved a place for ours next to his beautifully restored big-block ’67 ‘Vette. They were chromatic opposites—ours red with black on its stinger hood, his black with red—and attracted a lot of attention parked there side-by-side.

We finally sold the ’67 in 2006 when we bought an early-build “captured fleet” Pontiac Solstice for a very friendly price. Hardly an appropriate substitution, I know, but I had just written a book on that model, my wife had fallen in love with it, and we were a little tired (again) of the hassle and expense of old-car ownership. Besides being a beautiful, fine-handling, fun-to-drive, and affordable little sports car, the Solstice also came with a full factory warranty.

I have no high-speed, hard-driving, or close-call experiences to relate from my time with that ’67 Corvette. Unlike in my youth, as a highly responsible adult uninterested in taking chances or collecting tickets, I drove it like the valuable collectible it was. I also can’t find or recall how much we sold it for, but (given Lucas’ appraisal), I think it was something over $40K. Not bad for a six-year run with a really cool classic Corvette, even if it was a faux 427.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Hmmm. I’m not a Corvette owner, but seems to me that if this was essentially documented as a numbers-matching car (or at least could be made so fairly easily), it would make sense to source a proper hood and make the cosmetic changes to do away with the “faux” stigma. Would it not have been more valuable?

Unfortunately, owners of ’67 small block Corvettes that have the big block hood think that a previous owner installed that hood. But, they could be a small group of owners that have a very unusual factory built Corvette. The was an incident back in the day that caused a shortage of small block hoods. Chevrolet didn’t want to stop the assembly line and continued production with small block cars getting big block hoods.

Too bad that most of these owners don’t realize the uniqueness of their cars, and even worse for those that chunked that original hood to return their cars to “correctness”.

My understanding is that the story of small-block ’67 Corvettes with big-block hoods is a myth, as there is no documentation to support the story.

Big block hood or not a C2 is a beautiful car. I prefer without side pipes myself.

It seems amazing to me that the author can’t recall (or find documentation of) either his buying or selling price. Maybe he buys and sells cars like crazy. Me, I’ve only owned 23 cars through the years, but I can remember what I paid for my ‘64 Vette in ‘78 ($3,600) and what I sold it for in ‘80 ($5,300). But then, this Corvette was a milestone car for me.

May we all find ourselves so blessed to not need remember the $40,000 car sale here and there.

I once owned a ’65 L78 coupe. The previous owner blew it up and rebuilt it, as much as possible, to L88 specs. The car was a beast to drive, in part because of the more than abundant power, but also because it lacked power steering and power brakes! It should also have been ordered radio delete because you couldn’t hear anything because of the sidepipes. I still love the C2 styling. The C3 looks more “modern,” but, to me, the C2 always symbolizes the kind of sports car GM could produce if they set their mind to it. Fortunately, that Corvette tradition is still with us today.

Even though I am a long time NCRS member (25 years and counting), I would drive any Corvette, even if it had a Model T hood, to a car show, as long as I

was enjoying the car. And naysayers would just get a blank stare from me as they fussed over its non-original hood. Judging for points or a high value car is one thing, fun is totally something else again.