eMustang Driven: Alan Mann Racing trades “roar” for “whir”

The door shuts, the key turns, and there’s a whirring of the fuel pump before the starter motor cranks away and the engine catches. There’s an explosion as fuel is compressed and ignited, and the 5.75-liter V-8 settles to a chugga-chug-chug, fumes filling the air and hydrocarbon flecks spitting from the exhausts. It is everything and more you’d hope from a 1970 Ford Mustang Mach 1—theatrical, attention-seeking, and a hint of the anti-establishment, ready to melt rubber into the road and race for pink slips.

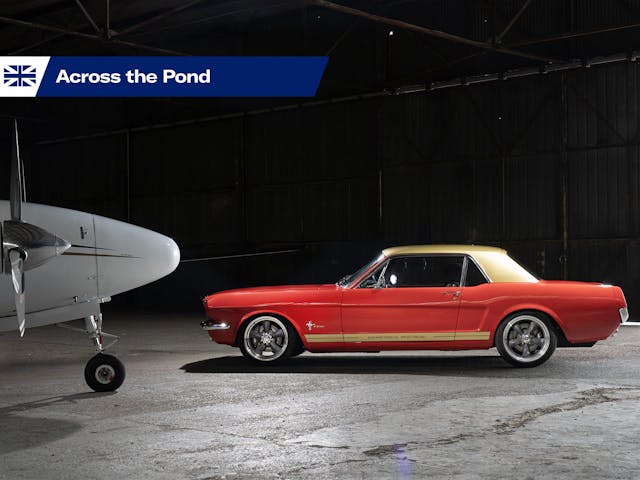

The Mach 1, however, is being moved to make way for a 1965 Mustang of an altogether different kind. When the key is turned in that car’s dashboard, there’s no explosion of internal combustion and no fumes from exhausts to melt the hairs in your nose and bring tears to your eyes. Instead, you hear the faint whir of electrical systems waking up and running checks. Then you turn the key further, ease down the brake pedal, and nudge the short shift lever from neutral to drive, before leaning into the accelerator.

The imperious hood of the Mustang coupe emerges from the workshop of Alan Mann Racing, and a passing driver of a delivery van appears somewhat perplexed that an American pony car is moving without making a sound—or rocking on its suspension to the beat of a V-8.

It may be equally perplexing to those familiar with Alan Mann Racing (AMR), the British team that ruled the grid during the swinging Sixties. The company was founded in 1964 by Alan Mann, after his success in motor racing impressed Ford so much that the carmaker effectively set him up as its European racing operation. Alan Mann Racing became part of the blue-blood brotherhood, and Fords would capture the most high-profile championships of the era, including the British Saloon Car Championship, the European Touring Car Challenge, and the FIA World GT Championship for Manufacturers. Meanwhile, the drivers behind the wheel were the best of the best: John Whitmore, Jacky Ickx, Bo “Bosse” Ljungfeldt, Graham Hill, Frank Gardner, Jackie Stewart, Richard Attwood, and Bruce McLaren all did battle in AMR cars.

Ford pulled the plug on its “Total Performance” strategy, and in turn its European satellite racing operation, at the end of 1969. Alan Mann switched to aviation, developing Fairoaks Airfield, on the doorstep of his old racing workshop in Surrey, as well as a successful helicopter leasing business. It wasn’t until 2003, and an opportunity to share driving duties at the Goodwood Revival, that Mann got the bug for racing again, reviving Alan Mann Racing for historic motorsport.

Mann died in 2012, which left AMR in the safe hands of his sons, Henry and Tom. Today, the workshop is a handful of miles from the site of the original garage in Byfleet. And the first question for Henry Mann is obvious: Why electrify a Mustang?

“We’d always wanted to do a Mustang restomod,” says Henry, “because we’d done so many rally and race Mustangs, and quite a lot of road cars too, and figured we could do a half-decent job of a restomod Mustang.” In February 2022, Ford contacted Henry and Tom, inviting the brothers to the unveiling of its Ford GT Alan Mann Heritage Edition, a special version of the supercar that paid tribute to AMR’s lightweight 1966 Ford GT experimental race cars. During the event, held at the Chicago Auto Show, Henry was rather taken by a 1978 F-100 pickup “Eluminator” concept that Ford had played around with, dropping out its straight-six engine and fitting the battery-electric powertrain and front and rear electric traction motors from a 2021 Mustang Mach-E GT. “It was really popular, and the lines to ride in it were huge. There was so much interest in it.”

While at the show, Henry met another Henry—another Henry Mann, in fact—who happened to be the first owner of the 2022 Ford GT Alan Mann Heritage Edition. The two concluded that an electrified Mustang with the Alan Mann Racing name attached to it would be a very cool thing indeed.

After more than a year of development, in partnership with Nick Mason, a former vehicle development engineer at Ford who founded EcoClassics in Maldon, Essex, AMR had a prototype up and running.

Henry explains that beneath the surface of this standard looking 1965 Mustang—called the Alan Mann Legacy ePower Mustang—sits an off-the-shelf inverter, motor, and battery management system, all sourced from China, while the two battery boxes were designed in Britain specifically to fit the Mustang. The motor and one battery sit in the engine bay, the other battery is in the boot, giving a 50/50 weight distribution, while power is sent to the back wheels through a Torsen limited-slip differential.

The battery is a 77-kWh unit, able to accept AC and DC charging, and is claimed to give a touring range of up to 220 miles. Using DC rapid charging, Henry Mann says the battery will charge from 20 to 80 per cent in 40 minutes. In muscle car terms, that all translates to an output of 300 hp, and there’s 228 lb-ft of torque as soon as you flex your right foot. For a 1965 Mustang, that’s impressive. It means the car is capable of accelerating from 0 to 60mph in 5.2 seconds, with a top speed of 97 mph.

On the rain-soaked roads around the company’s workshop, the silent Mustang provides a brisk turn of speed up to around 60 mph, in part thanks to impressive traction that comes from AMR’s years of experience building racing Mustangs. The suspension design has been changed to incorporate independent double wishbones with coilovers all around, and from a standstill there’s just the slightest skip from the back wheels as they claw at the road before the Mustang whines away.

That suspension is complemented by rack-and-pinion steering in place of the old worm-and-sector steering box, and together they create a more modern driving experience, where the car rides our lumpy, bumpy British roads better than a Mustang on rear leaf springs; it tracks true and straight and stays flat and planted through twists and turns. Admittedly, the steering is heavy—too heavy for some tastes, perhaps. But the weight when loaded up beyond the straight-ahead gives a feeling of confidence in what the front tires are up to.

As I make a beeline for the historic Old School Café, and a mug of builder’s tea, it’s clear that the car’s acceleration tails off beyond 60 mph, but it gets there briskly enough, and it’s arguably plenty enough for today’s busy roads. What’s not so welcome is a resonance coming from the propshaft, between 40 and 60 mph, something Henry Mann later tells me they’re working to remedy. There’s gentle energy regeneration when you lift from the throttle, and when you stand on the brake pedal, the effort and impressive stopping power of the uprated system (six-piston calipers at the front, four-piston items at the rear) remind me of the Jaguar I-Pace eTrophy racing car I drove a few years back.

There are other modifications, too, which will be welcomed by some. The updated instrument cluster, for example, looks period-correct but displays all the information an EV driver could want. Or the touchscreen infotainment system with Apple CarPlay and Android Auto. Best of all are the modern front seats, complete with integrated seatbelts, which are noteworthy for being so solidly mounted, while proudly displaying the Alan Mann Racing logo, stitched into the headrest. Perhaps the neatest touch of all, however, is the location of the charging port. When I ask Henry Mann where they’ve hidden it, he flips down the front number plate and there it is.

Sipping my tea at Old School Café, I wonder whether AMR team members and drivers may have gathered here, back in the Sixties, after shaking down race cars at the nearby Longcross test track (now used exclusively used for blockbuster filmmaking). I wonder what they might have thought of the ePower Mustang parked out front.

I jump back in the Mustang and drive past the track, and I encounter a large, smooth, open roundabout where it’s possible to explore the limits of grip. The suspension and steering, as well as the new bespoke subframes to carry the battery packs and motor, give the Mustang a robust feel. Old cars of this era should pitch, dive, roll, and heave on their suspension, while the body flexes under load, but there’s none of that in this Mustang, and when the tail does let go, I’m surprised at how high the limit of adhesion is.

At this stage, I can sense some will be shaking their heads at the thought of an electric classic Mustang. After all, the pony car was enjoyed by many as a tire-smoking attention-seeker, not a zero-emissions solution for London’s ever-expanding Ultra Low Emissions Zone. But given there were more than 1.3 million Mustangs made in the first two years of production alone, converting a small number to electric propulsion isn’t going to endanger the species.

Personally, I’d rather my Alan Mann Racing Mustang come with those suspension and brake upgrades, some additional structural bracing, and a rocking V-8 that shakes my neighbrs’ windows every time I start it up. After all, when you take the soundtrack out of an old car, all it serves to do is exaggerate the noise of all the other moving parts and squeaking trim.

I do wonder, however: Does the current approach not endanger the very existence of Alan Mann Racing? After all, if EV retro-fit conversions of classics really catch on across the hobby, might legislators take a dim view of fire-breathing racing cars and noisy, smelly race meetings?

I put that question to Henry. “I think with the rise of synthetic fuels, there’s plenty of argument for keeping these [racing cars] as they are. But I think some people are going to want electric just because of the tailpipe emissions issue, and the quietness and the more civilized behavior in a city, where you’re not belching out unburnt hydrocarbons when idling at the lights. And it’s such a negligible contribution to the overall emissions of the road transport fleet that I hope it [legislation] wouldn’t be changed.”

The thorny issue for potential buyers in Britain is that the extensive changes made during the conversion mean the car could not retain its original registration number. Instead, it would have to be submitted for an Individual Vehicle Approval test, and that would require further changes to the car, which AMR are weighing up “depending on customer demand.”

Interested parties in America, meanwhile, will be able to have the complete conversion carried out by Alan Mann Racing’s U.S. partner, Mann ePower Cars, based in Hatboro, Pennsylvania. The cost will be a minimum of $250,000 (£203,000), says Henry Mann, for a turn-key car. He adds that sum could be lowered if an owner has a donor car in good condition.

So, the retro-fit electrified Mustang is a curious thing on all sorts of levels. It’s not a muscle car as we know it. And it can’t be bought as a turn-key car in the U.K., only the US. And if you had the conversion carried out on your classic Mustang in the U.K., it would lose its original registration, due to the rule-makers at the DVLA. Such is the price of progress, I suppose.

Things used to be a lot simpler, and noisier, in the Sixties.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

In my opinion a waste of a good car.

$250k for a car with a loss of character. No thanks.