Get Spooled: Boost, and why people love it

Once limited to high-performance cars and airplanes, turbocharging has since become as ordinary as power seats. So much so that few customers using the technology every day understand what it is, how it works, or how it differs from its boosted cousin: supercharging. Boost is shorthand for the positive combustion chamber pressure created by a turbocharger or supercharger. Also known as forced induction, the point of this process is to direct additional air into the engine. More air means there can be more combustible fuel, all of which leads to more power.

My dad gave me his zippy red 2009 Chevrolet HHR SS, which features a boost gauge on the A-pillar. It’s fun to watch the boost gauge spike as the turbocharged 2.0-liter, four-cylinder engine kicks out 260 horsepower. It made me wonder: How did boost start? Where is it going now that electric vehicles are in the mix? Let’s find out.

But first, why does boost matter?

The point of boost, regardless of its form, is to increase power and/or torque. And for a lot of people, boost is synonymous with high performance for its own sake. Going fast is, in a word, fun.

Speed releases adrenaline, the hormone that causes your heart to beat faster and blood vessels to send more blood to your brain and body. If it sounds kind of like falling in love, that’s because it is. Popular culture reinforces this connection, from the Dukes of Hazzard and Knight Rider to the Fast & Furious franchise.

“Speed is something that has a very positive value in our society and if you look at car commercials, you can see the emphasis placed on going fast,” Leon James, a professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii, told NPR. “So in a lot of movies and lyric songs, children are exposed to that … it is the fact that we are culturally trained to have this relationship with speeding.”

When it comes to boost, though, turbocharging an engine isn’t all about power. Initially, inventors and engineers worked toward making engines more efficient, and in the case of aircraft, less prone to loss of power at altitude.

How superchargers and turbochargers got their start in aviation

The first attempt to use forced induction in a combustion engine dates back to 1885, when Gottlieb Daimler patented what would now be called a supercharger. Early production automobiles, however, generally only employed natural aspiration—intake air with pressure equal to that of the atmosphere. Once forced induction technology truly arrived and sufficiently evolved in aviation, it was appropriated for use on the road.

Swiss engineer Alfred Buchi filed a patent in 1905 for a unit that forced air into a diesel engine with a compressor driven by exhaust gasses. Twenty years later, Buchi showed that his turbocharging system could create a power increase of more than 40 percent. Meanwhile, turbochargers (then called turbo-superchargers) were applied to large marine diesel engines. In 1923, two German passenger liners were outfitted with turbodiesels and demonstrated the utility of this technology.

“The ships’ 10-cylinder engines were able to muster 2,500 hp, while their normally aspirated counterparts could only produce 1,750 hp,” John Lehenbauer wrote for Motor Trend.

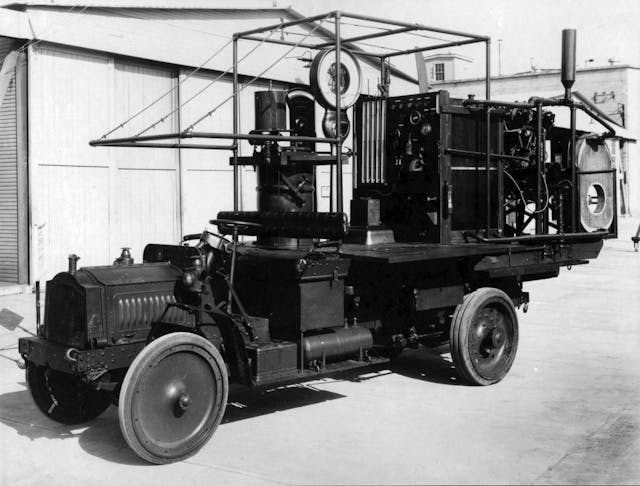

In the same era, an engineer named Sanford Alexander Moss and his team mounted a turbocharged V-12 and a dynamometer on the bed of a Packard truck. In 1918, they shipped the entire rig from Dayton, Ohio to Colorado Springs, Colorado and drove the truck 23 miles up the then-unpaved Pikes Peak Auto Highway. Once they reached the summit, Dr. Moss and the crew started testing the turbo V-12 setup at 14,000 feet above sea level to show how turbocharging counters power loss at high altitudes.

“Moss’s experiments decisively proved the merits of turbocharging,” Don Sherman wrote for Hagerty in 2022. “Baseline sea-level tests conducted at McCook had the Liberty producing a maximum of 354 hp at 1800 rpm. Atop Pikes Peak and without the turbo, output plummeted to 230 hp.”

Two years later, in 1920, a turbocharged 12-cylinder Liberty was installed in a Le Pere biplane and successfully flown to 33,000 feet. While the technology advanced too late for use in the First World War (1914–1918), fighter and bomber planes were subsequently built with turbochargers and set off into the skies en masse during the Second World War, faster and more efficient than before.

The birth of boost in cars

Technically, both superchargers and turbochargers are air compressors that push more oxygen—a key ingredient of combustion—into the powerplant. A supercharger is positioned in front of the internal combustion process, as part of the intake, and is driven by a belt from the engine’s crankshaft. It spins, creating a vacuum that pulls and squeezes air into the engine on its intake stroke. This air movement, in part, accounts for the high-pitched whistling sound typically described as a whine.

A turbocharger operates on a similar principle, instead using the car’s exhaust stream to spin a turbine. The turbine’s action then produces compressed air for the intake.

Turbochargers are generally more efficient [than superchargers], as the source of energy for the compressor of a turbocharger is the turbine versus the crankshaft. Powering the supercharger (via a belt) requires some power draw, while the turbine of a turbocharger is placed in the exhaust system where this energy is mostly otherwise released out of the tailpipe.

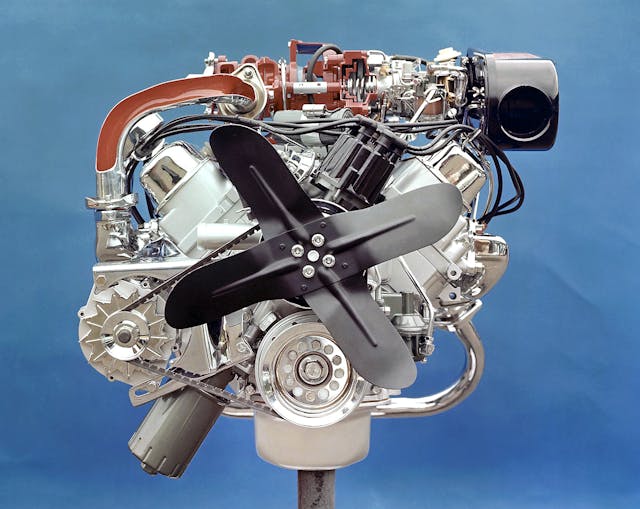

The 1962 Oldsmobile Jetfire Rocket not only has one of the coolest names in car history, it was the first production passenger car with a turbocharger. The unit was a bit high maintenance, however, requiring a half methanol/half distilled water injection between the carburetor and the turbo to run properly. Unfortunately, the Jetfire Rocket only lasted one year, but it and the turbo ’62 Corvair Monza made a big impression.

By the 1970s, turbochargers gradually became more predictable and reliable, and Formula 1 picked up the scent. The relationship between turbo boost and racing is probably the most prevalent reason we associate turbos with primarily with performance.

Widely known as the “godfather of turbo,” Gale Banks experimented with turbocharging marine and car engines throughout the 1970s, kicking off an aftermarket craze for GM’s 6.2-liter diesel and influencing the genesis of the Buick Grand National. A long time land speed racer, his engineering pushed the twin-turbo, big-block “Sundowner” 1968 Chevrolet Corvette to 240.738 miles per hour at Bonneville in 1982, laying claim to the title of “world’s fastest passenger car.”

Eventually, the technology trickled down, and for the 1989 model year even Chrysler minivans boasted a turbocharged four-cylinder.

High performance, but also high efficiency

Turbocharging is useful for performance, but it can also be a boon in pursuit of fuel economy and efficiency. Jason Fenske from Engineering Explained, er, explains it this way:

“The benefits [of using a turbo] are very real: The engine is smaller, it weighs less, it has [fewer] moving parts, you’ve got less friction, you’ve got less pumping loss,” he says. “So depending on the loading scenario on that engine and how you’re driving it, you can actually get really good fuel economy with small turbocharged engines.”

During the oil crisis of the 1970s, the automotive industry pursued turbos in earnest as a way to meet regulatory demands for improved fuel economy figures. By 1978, Mercedes-Benz launched the 300DS with a relatively fuel-efficient turbodiesel, all in a luxury package. Today, even mainstream cars from the Ford Escape to the Honda Civic use turbocharged engines to maximize performance and continually improve EPA-rated fuel economy.

There is, however, a misconception when it comes to turbocharged vehicles and fuel efficiency, says Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Group. Taking a naturally aspirated engine and simply adding a turbocharger on it will not improve fuel efficiency, the company says. The key is to also downsize the engine’s displacement; for example, if you compare a naturally aspirated 2.5-liter inline four-cylinder to a turbocharged 1.4-liter, the smaller engine could potentially match the performance figures of the larger non-turbo setup and still consume less fuel.

Turbo cars of today are much smoother and more drivable than many from the past. Jeep’s engineering team says that’s due to myriad advancements in turbomachinery, in addition to improvements concerning the rest of the powertrain geometry.

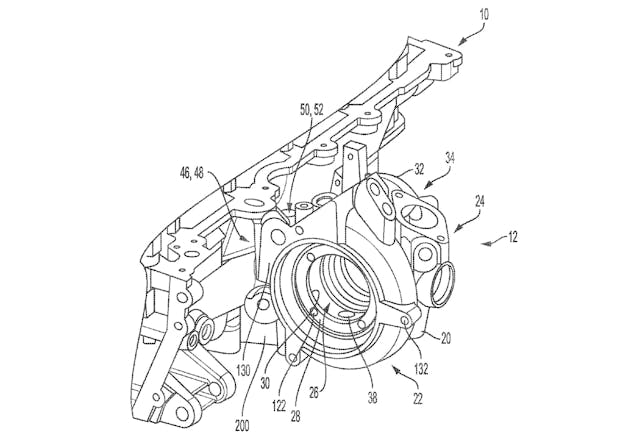

“Turbocharger-specific items such as VGT (variable turbine)/twin scroll turbines, low inertia rotor groups, and electric actuation are significant contributors,” said Michael Schmidt, a Stellantis engineer. “This reduces turbo lag and allows for torque generation at much lower revolutions per minute, preventing downshifts, (quicker/smoother/more linear response).”

Toyota’s chief engineer Sheldon Brown further contextualizes the evolution of turbos” “In the past, turbos were big and gave a performance boost later during the acceleration (lag),” Brown says. “Modern turbos are optimized to a smaller size with smoother air delivery to the chamber. Together with small transmission gear steps (8- and 10-speeds) they can provide smooth driving performance that feels like a large displacement engine, with the fuel economy and emissions performance of a smaller engine.”

Bursts of boost

Sometimes, a burst of speed is necessary—when passing, for example, or merging onto a highway. In these situations, anemic powerplants (not naming any names here) can struggle to summon sufficient power on demand for necessary maneuvers. Electric motors have changed the game in that aspect, since this technology provides near-immediate torque at low rpm.

Engineers specializing in EVs are now adapting to consumers’ expectations of “boost” by playing with electric motor software. Press the brightly colored Boost button on the steering wheel of a new Genesis GV60, and the all-electric system snaps the leash off the dual motors. For a glorious, hair-ruffling ten seconds, the GV60 gooses the horsepower from 429 to 483 and the torque jumps from 479 lb-ft to 516 lb-ft.

It’s not just pure-electric cars that can enjoy this benefit, however. The new Dodge Hornet R/T, a plug-in hybrid, includes a “PowerShot” feature, which gifts the driver a temporary boost of 30 horsepower from the rear-axle electric motor if they pull both shift paddles while in Sport mode and press the accelerator past the detent.

For something a little more extreme, pick any movie from the Fast & Furious series to witness the ludicrous boost from a tank (or ten) of nitrous oxide. Even casual drag racers might install nitrous, which splits into oxygen and nitrogen, adding more oxygen to the combustion process.

HowStuffWorks explains: “Nitrous oxide has another effect that improves performance even more. When it vaporizes, nitrous oxide provides a significant cooling effect on the intake air. When you reduce the intake air temperature, you increase the air’s density, and this provides even more oxygen inside the cylinder.”

Speaking of temperature, an intercooler plays an important role in any forced-induction setup, sending compressed air through a series of fins and coils to lower its temperature. Stuffing more air into an engine has consequences, after all, and the intercooler keeps the environment from overheating.

“If you take a plastic bag and close it with some air and squeeze it but don’t pop it, what do you notice?” asks Schmidt. “It gets hot! This is a downside to compressing air, and engines do not like hot air. They can make more power when they are fed colder/denser air; this is why we use intercoolers.”

What’s next? If the current crop of high-powered gas and electric cars are any indication, people still want big power and performance. For bursts of speed on demand, software is an invaluable tool. In the Kia EV6 GT for example, toggling between drive modes changes the dynamic significantly: Eco mode keeps it mild at 286 hp, while Sport can kick out as much as 429 hp. Down the line, as engineers figure out how to make EVs more efficient, charge more quickly, and go further, we’d bet that the nature of speed—and bursts of it—will continue to evolve.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I absolutely consider boost a safety feature. As important as good brakes. More so on the supercharger side, but my turbo-cars will definitely get me out of a highway pinch when needed.

How did an article on boost turn into an electric fanboy/fangirl article? Is this motor trend now?

I think it would be more accurate to state positive intake manifold pressure as opposed to positive combustion chamber pressure. If your NA motor is not achieving positive combustion chamber pressures, you have problems

My general understanding of the development of the turbo was that it was originally intended to maintain neutral (1 atmosphere) pressure in the intakes of high altitude aircraft – so they would perform the same as at sea level. It wasn’t until folks started playing around with them that they realized that hey… 2 atm = go fast… I’m gonna put this thing on my car.

I seriously doubt that there is any appreciable difference in efficiency/load on the engine between turbochargers and superchargers. If you are powering a compressor, the laws of thermodynamics pretty much dictate that that power is being stolen from the engine somehow. It is my understanding that the primary difference is that turbos respond to load where superchargers only respond to RPM. Your supercharged engine will always act like a bigger engine at all points on the RPM band. Turbocharged engines only act like a bigger engine when you put your boot in the throttle