The Brooklyn Bridge just turned 140

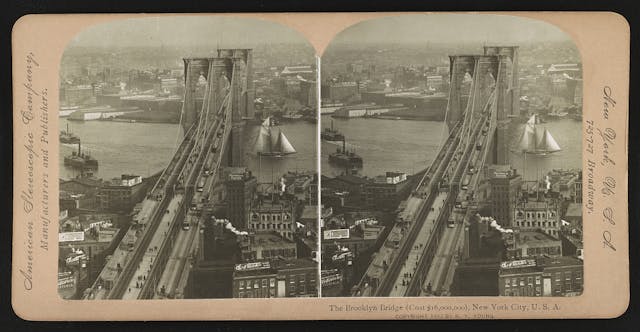

The Bridge. By May 24, 1883, the official opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, New Yorkers didn’t need to use its official name. It was simply The Bridge, a 1.1-mile structure over the East River that not only linked the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn but also put its stamp on Gotham as The City.

When the Brooklyn Bridge opened 140 years ago, no other municipality in America—no other city in the world, for that matter—had a suspension bridge as long or majestic. Both functional and artistic, it remains one of New York’s best-known and most-visited attractions. Its ability to inspire is difficult to put into words.

“The bridge was, not just for New York but for America in general, the great symbol of 19th-century progress and optimism,” says Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic for The New York Times. “It was of an era that we now forget was an extraordinary time of change and connection. You had the transcontinental railroad. You had the transoceanic cable. You had the Suez Canal. All of these were being built around the same time. We were shrinking the world.

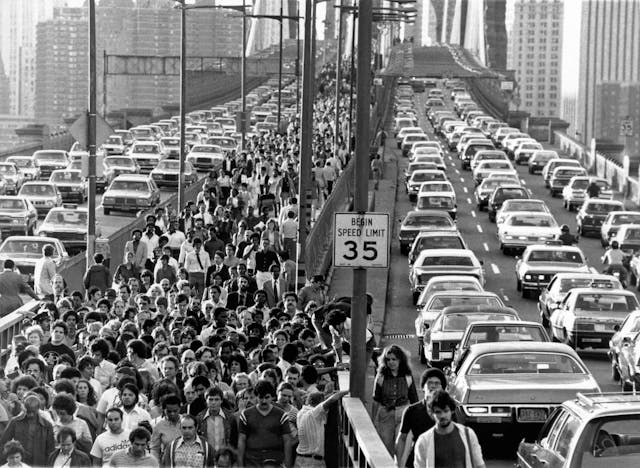

“In New York itself, the bridge tied together two separate cities, Brooklyn and New York, in anticipation of what became the one great city … But the bridge did something else; it created a public street, a great public square in midair, this enormous road that literally connected the two. They suddenly became one. That’s a big reason the bridge remains our great civic symbol of hope and of possibility.”

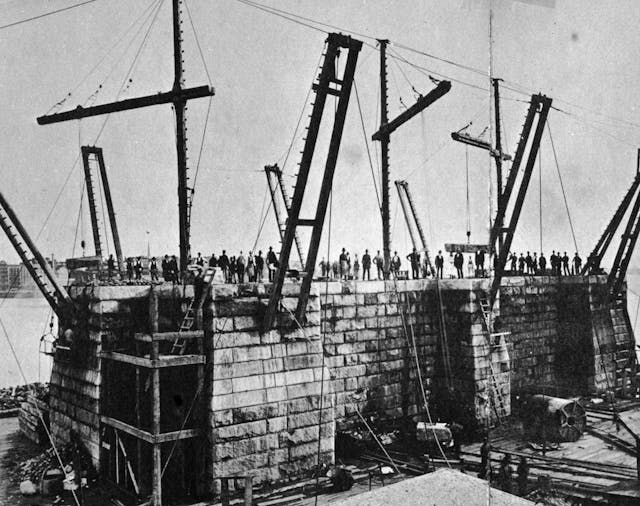

Designed by German immigrant John A. Roebling, the Brooklyn Bridge took 14 years to complete, and for good reason. Not only were the swift waters of the East River a concern, but the bridge had to be tall enough to allow ships to easily pass beneath it. The bridge’s two granite foundations were built in watertight timber caissons that descended 78 feet into the riverbed on the New York side and 44 feet on the Brooklyn side. Each tower rose 278.25 feet above the water—119.25 feet from the water to the bridge itself, and another 159 feet to the top of the stone arches.

Danger lurked above and below the water and made working conditions difficult. According to History.com, compressed air pressurized the caissons to allow underwater construction, but little was known of the risks of working under these conditions. More than 100 workers suffered compression sickness (commonly known as “the bends”). There were also collapses and a fire.

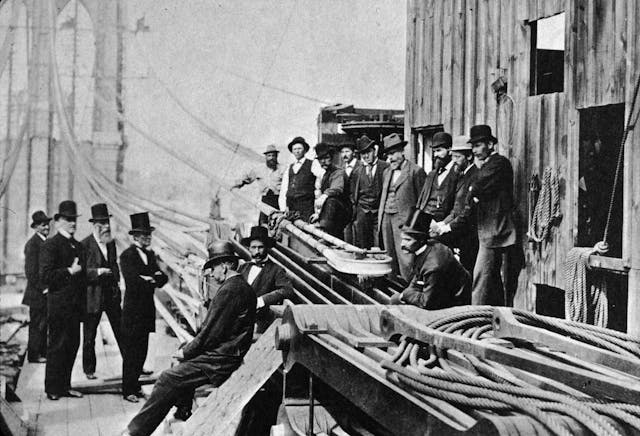

At least 20 workers died during the bridge’s construction, the most notable loss being its designer. Shortly after work began in 1869, John Roebling’s foot was crushed by an arriving ferry, and he had to have several toes amputated. His condition worsened over the next three weeks, and he died of tetanus on July 22, 1869.

Roebling’s son, Washington Roebling, took over as chief engineer of the project, but two years into the construction he too suffered compression sickness, which left him paralyzed. His wife, Emily Warren Roebling, who taught herself bridge construction, assumed much of the chief engineer’s duties and oversaw the bridge’s completion.

The highly anticipated opening of the Brooklyn Bridge—hailed as “The Eighth Wonder of the World”—was attended by thousands, including schoolchildren and workers, who were given a rare day off. Among those who participated in the opening ceremony were President Chester Arthur and New York governor Grover Cleveland.

Long before the motor vehicles were invented, the bridge accommodated horse-drawn carriages and train trolley traffic, but as of 2018 it saw an average of 116,000 vehicles, 30,000 pedestrians, and 3000 cyclists each day. The popular walkway above the highway portion of the bridge offers majestic views of the city.

Recently, The New York Times’ Kimmelman walked the bridge with documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, whose 1981 project about the bridge earned him an Oscar nomination. The two discussed the structure’s lasting impact and what it means to those who interact with it both daily and occasionally. Burns admits the Brooklyn Bridge inspired him to leave a positive mark on the world, just like Roebling did, and Kimmelman says he isn’t the only one to feel its motivational power.

“Roebling represents so much about America of that moment … the immigrant, the dreamer, the inventor,” Kimmelman says. “He had spiritual beliefs that sort of brought him here. So there was something about him that was like the bridge—the kind of emblem of America at that time.”

The Brooklyn Bridge was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1972.

According to the Library of Congress, it cost $16 million to build, or nearly $500 million today. The bridge has undergone millions of dollars in improvements over the years—including rehabilitation of the approaches and ramp superstructure from 2010–17 for $650 million—but it’s difficult to put a price on its value to the city and the history of America.

“There’s something reassuring about the bridge—about our ability as a city to strive for and achieve great, impossible things,” Kimmelman tells The New York Times. “It’s really remarkable that 140 years later, it continues to have this role in our lives as a reminder of what we are capable of … In a city where we often feel overwhelmed or battered, the bridge is a place to go to consider what New York is at heart, which is a place of dreams and aspirations.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Thanks for a very informative and entertaining article.

There are a number of excellent documentaries on the concept, planning, financing and building of this amazing and iconic American structure.

As Brooklyn didn’t become a Borough of Greater New York until 1898, it was still an independent City when The Bridge opened; (a sign stating “Welcome to Brooklyn: the Second-Largest City in America” existed for some years.)

What a superb accomplishment. The ability of men to create such things constantly amazes me. Nice article!