This ’68 Hurst Olds was a laborer before it was a labor of love

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Mine is a story about a victory for the little guy—the guy who doesn’t have the resources to have a car restored by professionals.

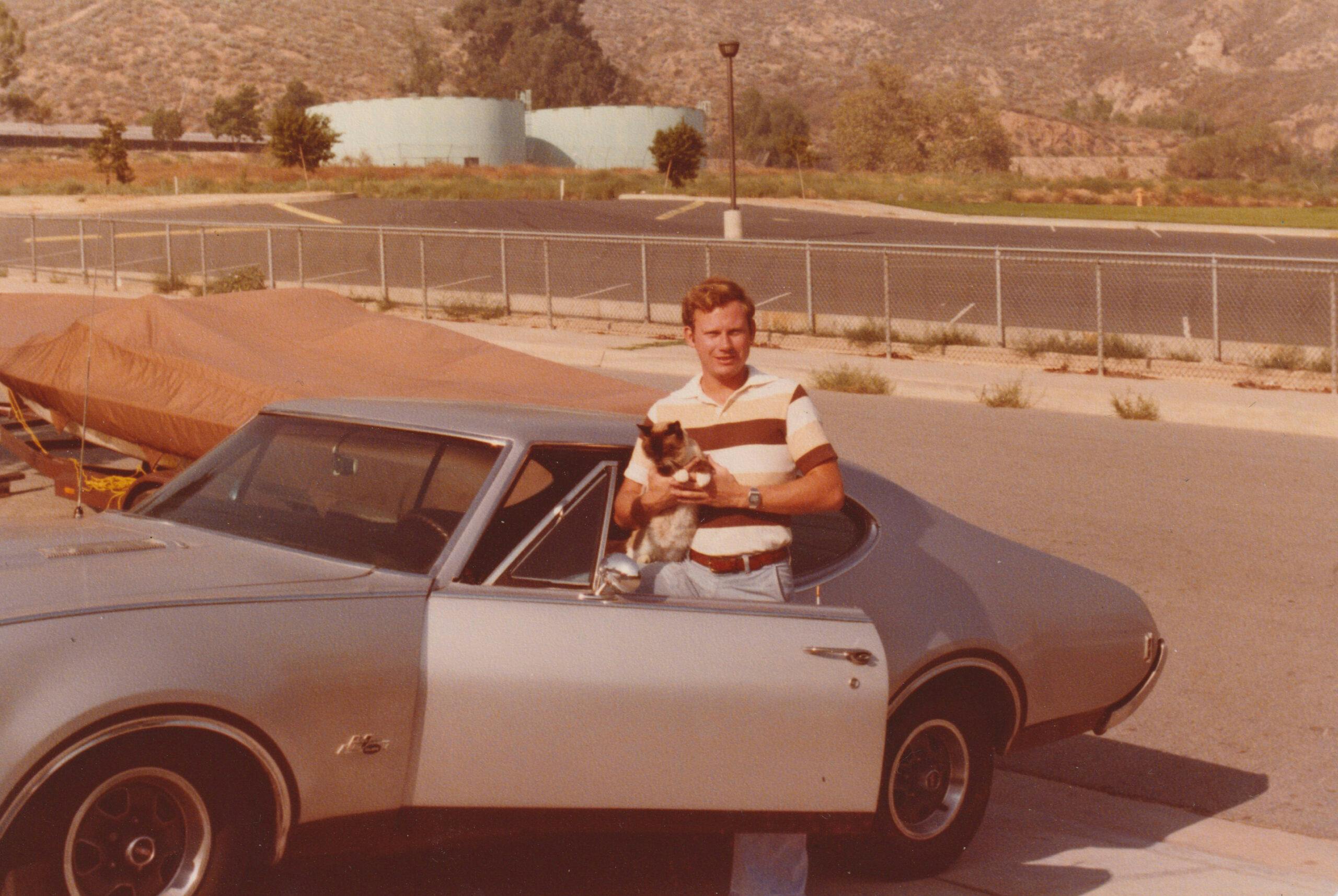

Growing up, my family always owned Oldsmobiles—a 1956 98, then a ’61 Dynamic 88, and finally a ’66 Toronado. In 1975, while serving in the U.S. Air Force in Southern California, I bought my own, a 1968 Hurst Olds, because I needed to pull a 21-foot ski boat. No surprise this 10-mpg car was on the used-car lot just after the first oil crunch. But it was cool and came with the very reasonable price of $1350.

After my honorable discharge, the Olds and I towed the boat to Colorado, and from there, we trailered a 1926 Model T to Atlanta, where I resided. The Olds was a workhorse in Atlanta, and I towed many yards of concrete for various projects with this car. Finally, after several years as a daily driver, with 51,688 original miles on the odometer, I parked it in my garage, where it sat for over 20 years.

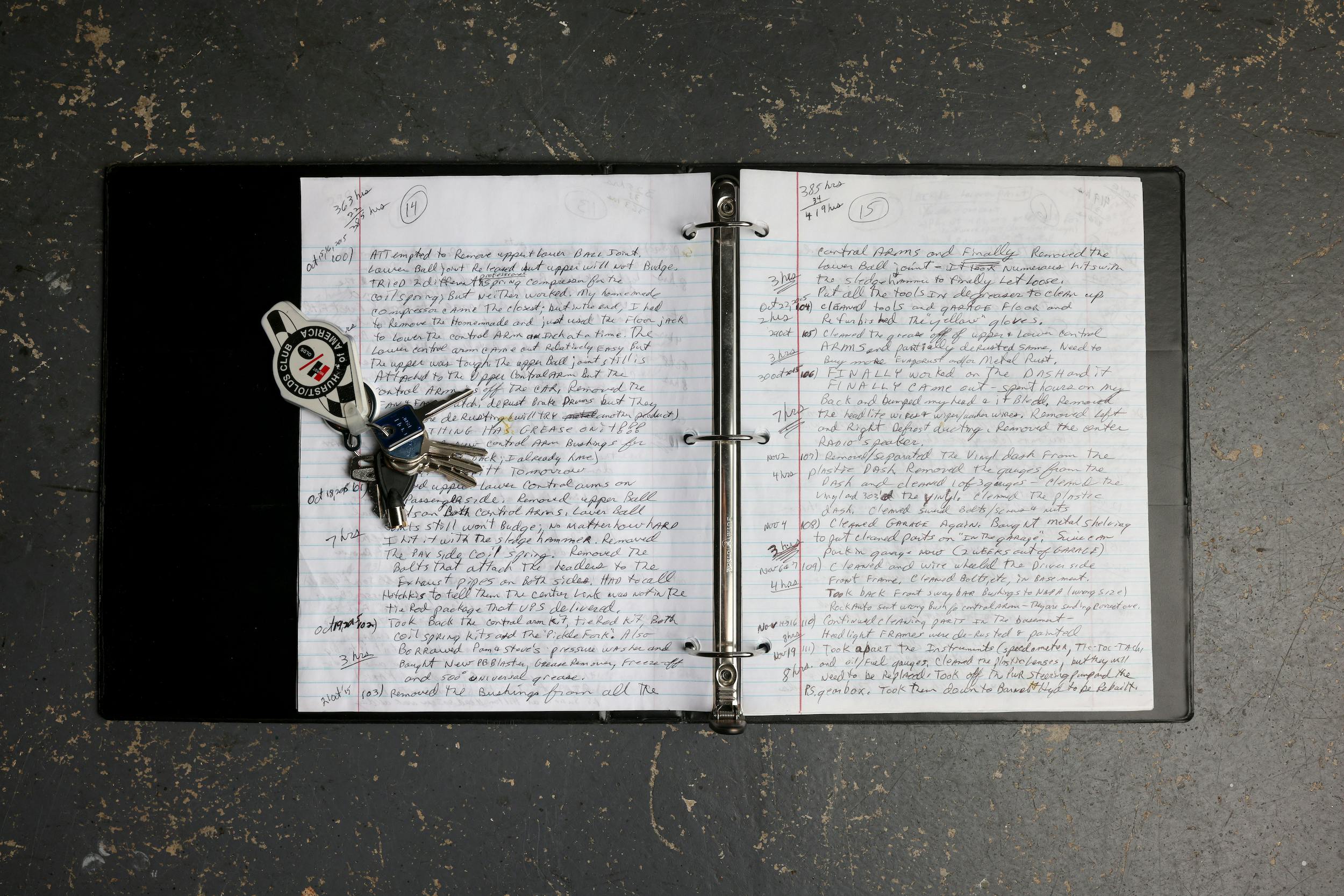

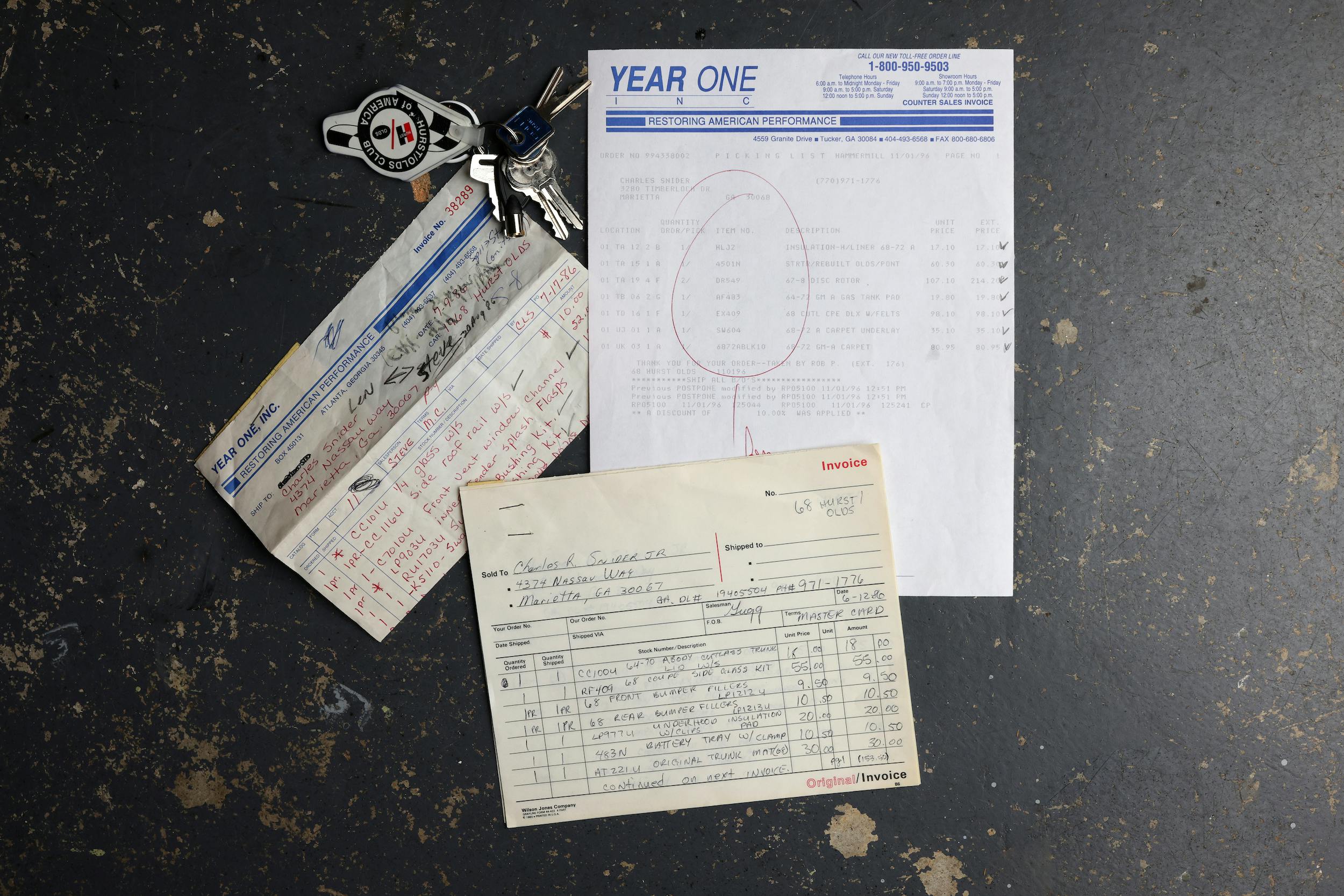

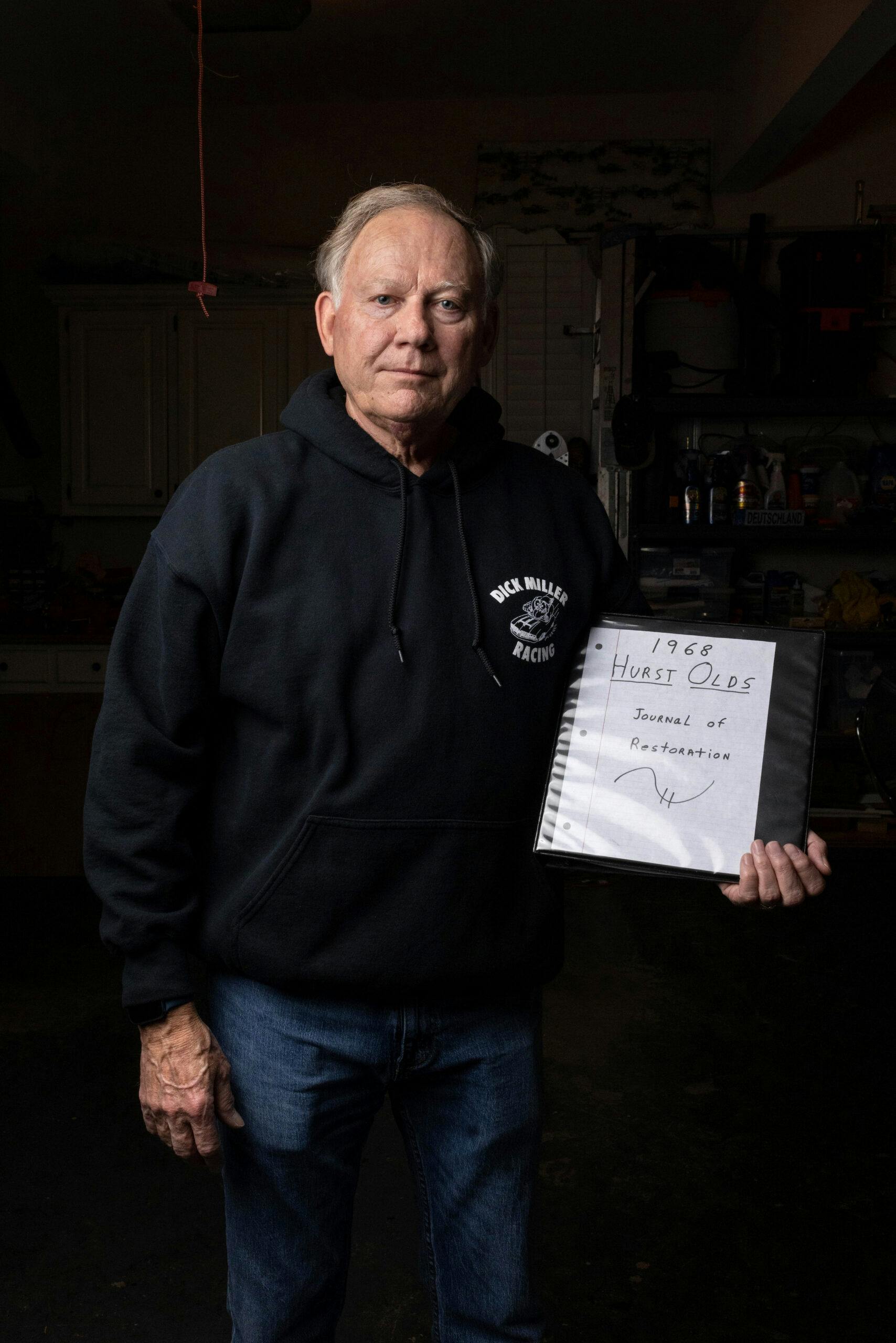

A while back, I started researching the car. I found my Hurst Olds to be a rare one, with only 515 produced and only 146 with air conditioning, which is my case. So I decided to restore the car in my garage. On July 15, 2013, I started the restoration, along with a journal. Five years, three months, and three days later, I finished the restoration and the journal, which contained 45 pages of handwritten documentation, plus a tally of the hours I spent on the job: 1046.

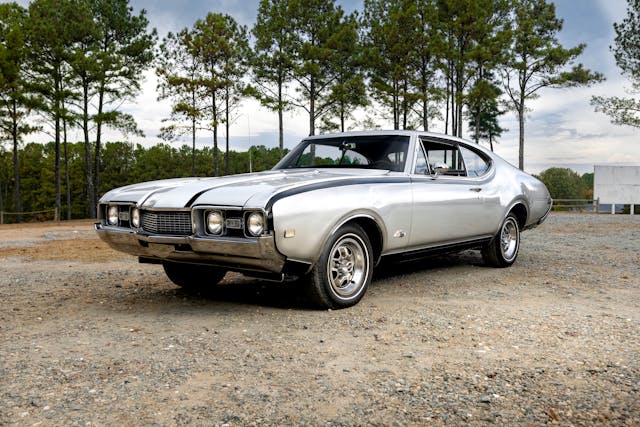

The ’68 Hurst Olds was the first car to carry the Hurst badge. Mine has a numbers-matching four-barrel 455-cubic-inch V-8 with under-bumper scoops, Tic Toc Tach, Hurst dual-gate shifter, front disc brakes, a Turbo 400 transmission, and factory air. I did 90 percent of the restoration myself, with my wife, Susie, and son, Justin, helping along the way. Of course, in anticipation of someday restoring the car, I had been buying parts for over 20 years, including many new-old-stock bits.

My restoration included completely rewiring the car, replacing all the fluid lines, changing the headliner, installing a new gas tank, removing the seats, adding a new air conditioner (from R12 to R134a), installing a new heater core, refurbishing the dash, reinstalling windows, replacing the front end (including new coil springs, tie rods, shock absorbers, and a rebuilt steering column), installing new brakes, mating the rebuilt engine to the rebuilt transmission, installing the driveshaft to the refurbished rear end and axles, installing the front and rear bumpers, and polishing all the exterior trim. Just about everything, in other words.

All of that was child’s play, however, because this project also had a scary part: removing the body of the car from the frame. By myself. With an engine hoist, a floor jack, four sawhorses, and two 8-foot four-by-fours. I accomplished this feat by first lifting the front of the body with the engine hoist and stabilizing it with various sizes of wood and shims. I then lifted the rear of the car using the floor jack and stabilized that with wood and shims. I inched the body high enough to slide in the sawhorses and the four-by-fours for support. Only then could I roll out the frame for a good cleaning and painting.

Then came reassembly, which meant rolling the frame back under the body and the precarious job of lowering the body onto the new body mounts. It was a slow, painstaking, inch-by-inch affair, with plenty of shuffling back and forth from the engine hoist to the floor jack to remove shims and wood blocks along the way. But by some miracle, the body slipped onto the frame like a glove.

The car then spent 14 months in the body and paint shop. The only rust was under the trim pieces of the windshield and the rear window, and once that was addressed, the Olds was primed, sanded, and painted in the correct paint scheme—including pinstripes and clearcoats. The shop finished up by installing the engine and transmission.

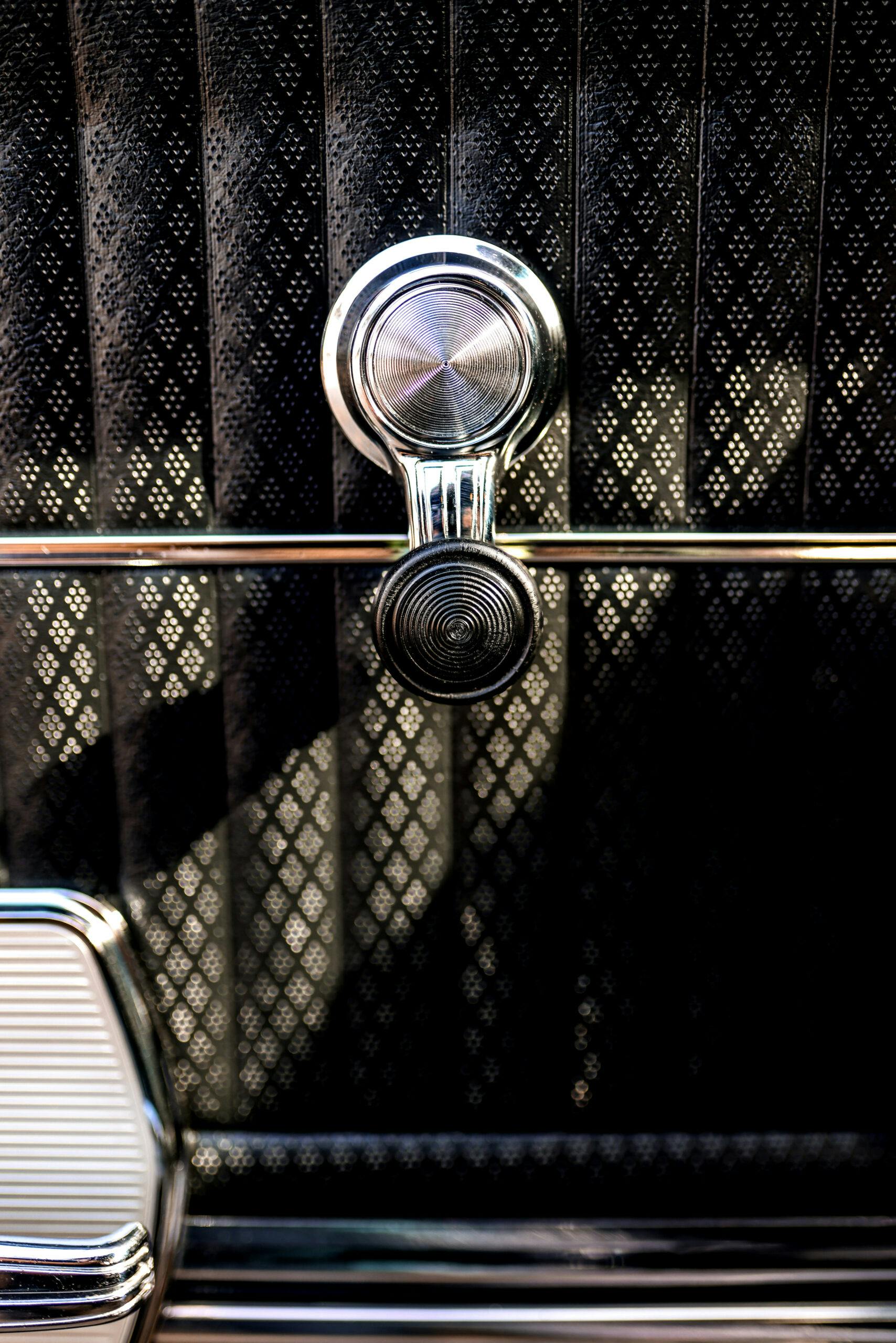

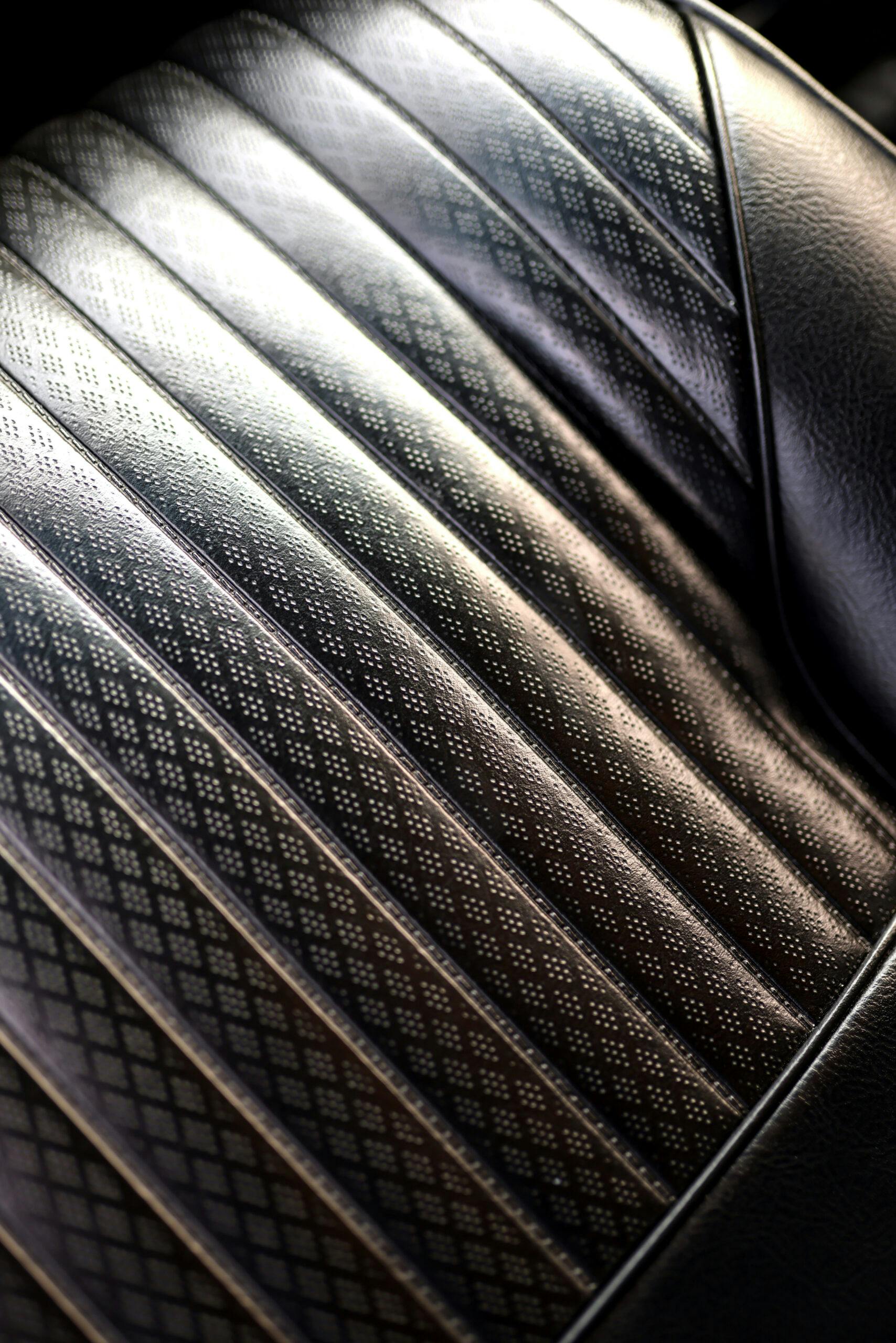

Back in my garage, I took a deep breath and began to reassemble the interior—new insulation, new headliner, window mechanisms, door panels, carpet, seat belts, that great Hurst shifter. I rewired the dash with the restored gauges, then put in the front bucket and rear bench seats.

I took it back to the shop to have the experts double-check my work, and on October 18, 2018, at 3:40 p.m., I fired up my ’68 Hurst Olds for the first time in more than 20 years. I was so proud to drive it home.

The next April, I entered it in the Peach Blossom BOPC (Buick-Olds-Pontiac-Cadillac) show. To my surprise and delight—in the first car show I’d ever entered—the Olds took first place. Since then, I’ve taken it to several other shows across the state and gathered another four awards. The Atlanta Concours d’Elegance even invited me to the event because I have the only 1968 Hurst Olds in Georgia.

With the five-plus years of work and restoration finally over, I love driving my Hurst Olds again, attending shows, and telling my story.

Victory, indeed.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Had one back in 76. I thought it fast and the shifter for drag or hard acceleration not so much. Never paid attention to mpg, this was in San Francisco. Remembered the sound it made when you punched it on the freeway. It had high miles and sold it to a mechanic friend for about $400. New it was rare.

Love the extra flair Olds added, great car. Love gen 2 A bodies. 68 GTO owner here!

I wonder how much he paid for the car back in 1975 ?