50 years ago, the Mercedes-Benz ESF 22 forecast the future

Many of us look back at the muscle car era as “the good ol’ days,” but long before the energy crisis put the kibosh on high-end performance engines in the 1970s, the U.S. Department of Transportation was already concerned that vehicle safety couldn’t keep up with all that power and speed.

With car crashes on the rise as the decade of the ’60s came to a close, the DOT focused on safety innovation. To help advance its goals, the department hosted a Technical Conference of the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles in 1968 and encouraged automakers to develop Experimental Safety Vehicles (ESVs). The DOT had ambitious aspirations, like ensuring that occupants survive a front or rear crash into a rigid barrier at 49.6 mph and side impacts against a fixed pole at 12.4 mph. Front and rear bumper impacts at 10 mph were required to leave no permanent damage to the vehicle. Braking from 60 mph to a complete stop was expected within 155 feet or less. Automakers were also encouraged to develop automated seat belt systems (which would eventually lead to their routine use by all drivers).

Germany’s Mercedes-Benz, which as early as 1959 had raised standards with the safety bodyshell of its “Fintail” saloons, was among the car manufacturers that accepted the challenge, along with General Motors, Volkswagen, and Volvo. Over the next four years, Mercedes constructed 35 safety vehicles—referred to as ESFs in Germany—which were based on five experimental models. The company’s third iteration, the ESF 22, just turned 50 years old.

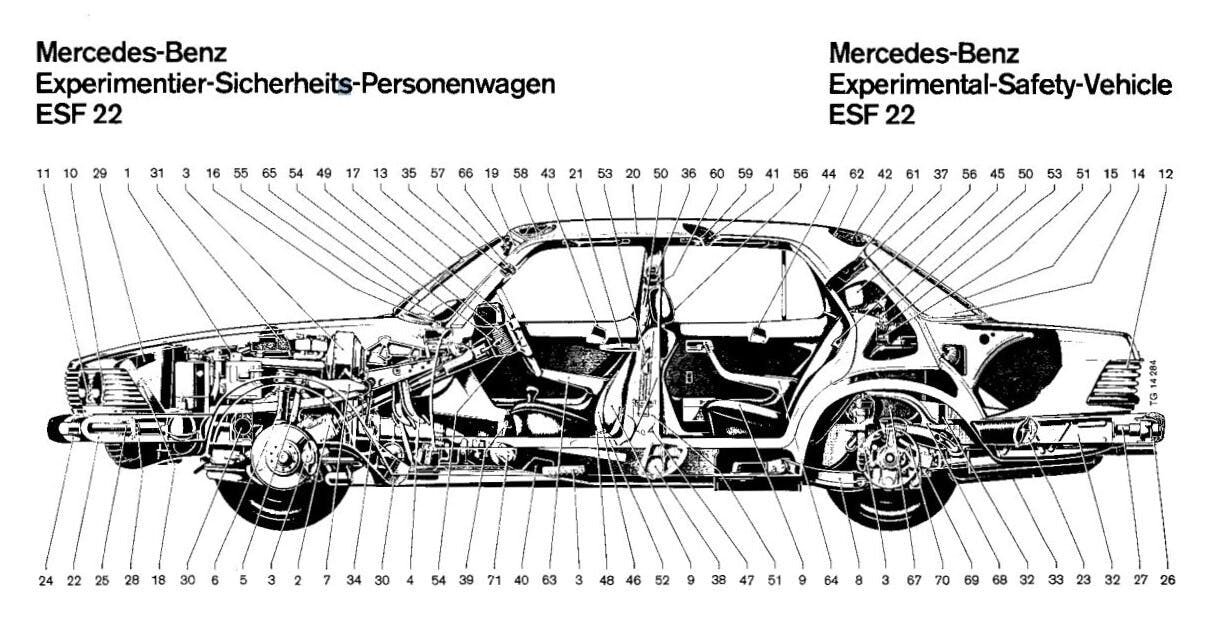

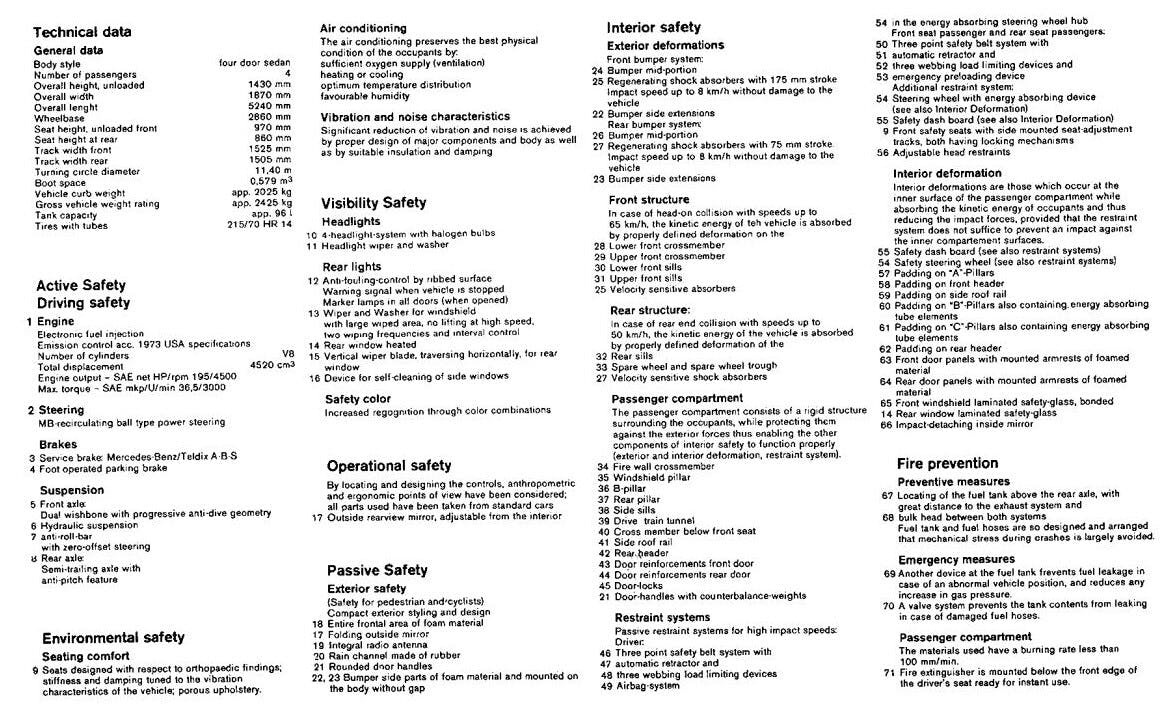

While the Stuttgart-based automaker’s first two experimental safety cars were based on W114 sedans—and were noteworthy for their smooth interior areas, ABS, headlamp wipers, and bodyshell improvements—the ESF 22 started as a W116 (S-Class) sedan. While attempting to maintain a conventional design, the front end of the ESF 22 stands out. It makes extensive use of plastic, deleting the typical chrome radiator grille and instead using the front section of an SL sports car, with a large central star, wrapped in impact-absorbing material. The headlamps are also surrounded by this substance and are recessed slightly. The bumpers are likewise designed to absorb energy.

“The front section alone is already a tour de force of the engineers in the service of safety,” Mercedes-Benz said then.

The impact technology didn’t quite meet the front/rear impact standard set by the DOT, but the other impact zones were better. The ESF 22 was built to withstand a frontal solid-barrier impact of 40.3 mph, a frontal pole impact of 31 mph, a side impact from another vehicle of 35 mph, a side impact from a stationary pole of 12.4 mph, and a rear impact of 31 mph.

Additional safety features in the ESF 22, which is powered by a 4.5-liter V-8 engine, include padded steering wheel and dash, and three-point seat-belt harnesses, each with force limiters and belt pre-tensioners; the driver’s harness has a force-limiting feature and an airbag. The car also received anti-lock brakes, a common feature in today’s automobiles but a revolutionary safety advancement in 1973. All of the safety features added 631 pounds to the weight of a standard S-Class sedan.

Many of those safety elements were incorporated into the W116 S-Class and later models.

The ESF 22 was unveiled at the fourth International ESV Conference in Kyoto, Japan, in March 1973. In the DOT’s official report on the conference, Daimler-Benz AG Chief Engineer Dr. Hans Scherenberg explained why the ESF 22 could never reach mass production.

“The research vehicle shows 660 pounds of additional weight,” Scherenberg said. “A further increase by 140 pounds would be inevitable should the drive train and the driving gear have to withstand a durability test. As a result of the requirements for higher engine output with increased weight, both fuel consumption and exhaust gas flow will be increased by about 10 to 15 percent. For these reasons, the ESF 22 cannot be regarded as an economically feasible solution for mass production.”

However, Scherenberg reasoned that many of the advancements should be incorporated into new vehicles. He was especially encouraged by ESF 22’s three-point seat belts and emphasized that countries should consider mandatory seat belt laws. (Eleven years later, on December 1, 1984, New York became the first state to make that happen.)

“The belts in today’s mass-production cars are designed for the 30-mph frontal collision. These belts could help prevent more than half of all severe and fatal injuries, if each occupant would wear them,” Scherenberg explained. “The new experimental belts offer corresponding survivability up to 40-mph frontal collisions. It is justified to assume that they could prevent a considerable additional number of severe and fatal injuries. At the same time, modern retractor belts are easy to handle, convenient to wear, permit sufficient freedom of motion and are reliable.

“In view of these factors, it would be inexplicable if the majority of car occupants would refuse to wear belts in the future. Furthermore, such a rejection would not be tolerable, and so, only one consequence remains—a legal requirement to use belts.”

Scherenberg emphasized that the ESV program “has led to new questions. This is not to say that it has not been worthwhile, but now these questions must be precisely formulated and investigated before we attempt to establish any new program.”

Although most of Mercedes-Benz’s experimental safety automobiles were created in the ’70s, the automaker’s quest for safety innovation continues today. Its most recent ESV, the ESF 2019, was presented four years ago, and the electric EQXX prototype (unveiled in 2021) showcases some of the engineering that will trickle down to future battery-powered cars.

The 50-year-old ESF 22 is currently on display in the Mercedes-Benz Museum as part of Mercedes’ “Close-up” series. Once considered a groundbreaking experimental project, it serves as a tribute to the work of engineers from Mercedes-Benz and a symbol of how far automobile safety has come since 1973, thanks to a nudge from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

It has a very blunt but small nose. It’s interesting in the looks but not as good as the contemporary production cars of it’s time.

“it would be inexplicable if the majority of car occupants would refuse to wear belts in the future. Furthermore, such a rejection would not be tolerable, and so, only one consequence remains—a legal requirement to use belts.”

Government, save me from myself. Add 50 years, here we are. No more moonshots, stay indoors.

Yes if you are that ignorant then the government has no choice. In countries with universal healthcare (yes countries with a moral compass) billions of health dollars have been saved by mandatory seat belt usage. The intelligent countries also control the usage of assault weapons and restrict them to the military where they were intended. You no doubt would question that too?

Brainless people do brainless things. Our government is part of the brainless problem. Look at public education and what it raises. I don’t need the government to tell me to take care of myself. I wore a seatbelt before it became a law. It became a law because insurance companies felt it would lower the injury payouts. Nothing about helping “society”. Also, it takes a person to pull a trigger.