Coupé Simone: Mysterious “lost” Duesenberg will soon be reborn

A few years ago, Hagerty columnist Jay Leno reconstructed a 1931 Duesenberg Model J LaGrande Coupe, one of six built in the style. The original body had been removed and scrapped in the 1940s by a Ford-Lincoln dealer in Indianapolis, which replaced it with a hideous, bulbous, self-designed mess of a body. Restoring such an irreplaceable classic to its original build standards takes serious funding and unparalleled expertise, as you might expect. Leno’s car was reborn thanks to the historical knowledge and restoration expertise of Randy Ema, the renowned Duesenberg historian who today owns the storied brand.

Such resources, both human and financial, are not always available.

Twenty-five years ago, for instance, two ambitious model car designers set out to recreate a somewhat mythical, “lost” Duesenberg. All they had to go on was a chassis number, an old story, a trunk full of memories.

The Coupé Simone

The Duesenberg, nicknamed Coupé Simone by its original buyer, was regarded as one of just a few examples bodied on Model J chassis that were left over after E.L. Cord dissolved his Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg luxury car empire in 1937. As the story goes, it vanished after delivery in war-torn Europe and never seen in public.

The story of the lost Duesenberg developed a following in enthusiast circles on the nascent internet in the 1990s, gaining a legendary status that continues even today. Wider public interest in the Coupé Simone took root in 1998, when the Franklin Mint produced a 1/24-scale model of the car. (After succeeding with commemorative coins, plates, and costume jewelry, the Mint moved into the high-quality collectible automobile model industry.) The Mint then followed up with a 10th-anniversary edition model in 2008; known as the “Midnight Ghost,” it was based on the supercharged Model J chassis (the so-called SJ) and wore a different color scheme that the original buyer had reportedly rejected in period as “too fast and menacing.”

The plot, you see, thickens.

Duesenberg: Redux

After 25 years of being limited to scale models, magazine stories, and internet legends by which to remember the mysterious Duesenberg, the classic car world will soon welcome a real, drivable Coupé Simone. Construction on the real-life chassis begins next week.

Greg Martin’s Iconic Rod and Custom in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, is experienced in traditional coachbuilding methods. Martin is being assisted by the Franklin Mint model’s original designers, as well as modern digital imaging tools.

Duesenberg aficionados will recognize Williamsport as the home of Lycoming Foundry and Machine Co., a member business of the same Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg family that built the legendary Duesenberg 420-cubic-inch, dual-overhead-cam, 32-valve straight-eight engines. Another auspicious connection: The Coupé Simone, as the legend goes, emerged from a small and obscure coachbuilder located in Green Brier, Pennsylvania, just 60 miles from Williamsport. Its name was Emmett-Armand Coachworks of America.

Despite this, history books seem to have no record of the Emmett-Armand Coachworks that supposedly made the Coupé Simone body. Why would that be? And why did all the principals involved, including the original builders—Emmett Hardnock and Armand Minasian—seemingly disappear without a trace?

With a little trip in the Wayback Machine, we will discover how an exercise in art imitating life morphed into life imitating art.

***

It began with a barn find

In February 1997, Automobile magazine ran a six-page feature story on a fascinating “barn find” discovery of a “lost” one-off Duesenberg bodied in 1939. In this case, the barn held no car—just a chest full of design drawings, correspondence with a buyer, and numerous other artifacts from the obscure Emmett-Armand Coachworks.

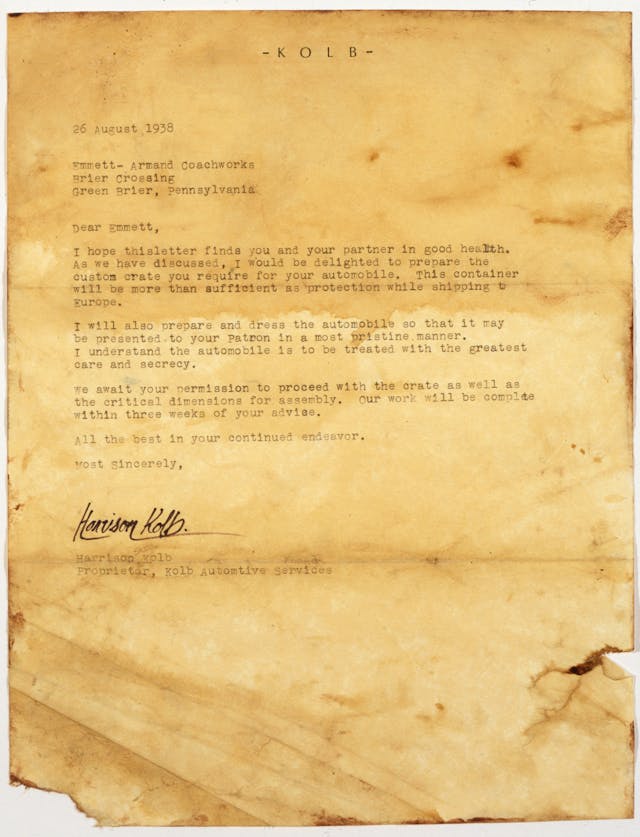

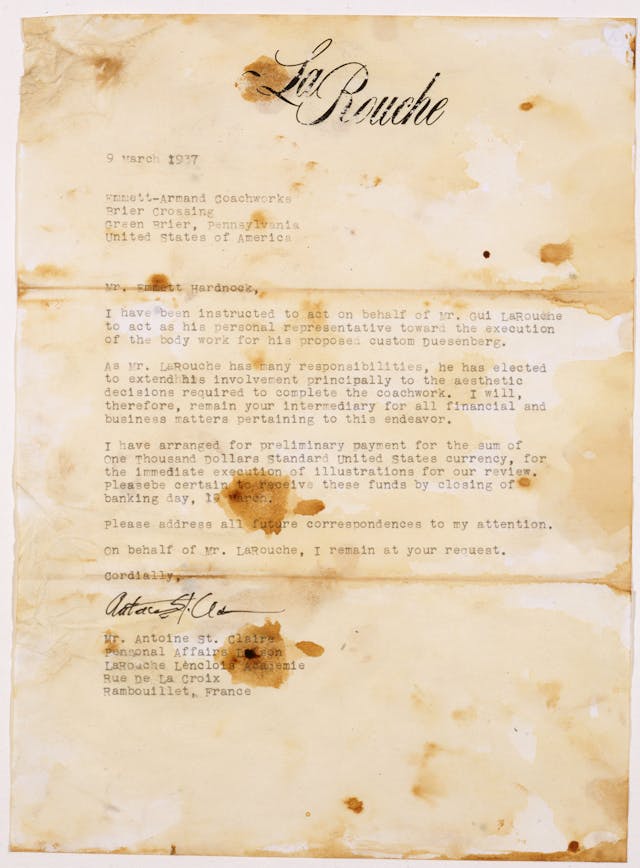

As the story goes, two Franklin Mint Precision Models designers were attending the Mint’s Antique Auto Show in 1995 when they were approached by a young man showing a 1932 Cadillac coupe. There was, the young man said an elderly woman in his home town of Green Brier, Pennsylvania with an old car, parts, and tools in a barn. The woman had kept it all safe for decades “in the hope that her husband, lost in the war, would return.” Intrigued by the tale, the two designers drove to Green Brier to investigate.

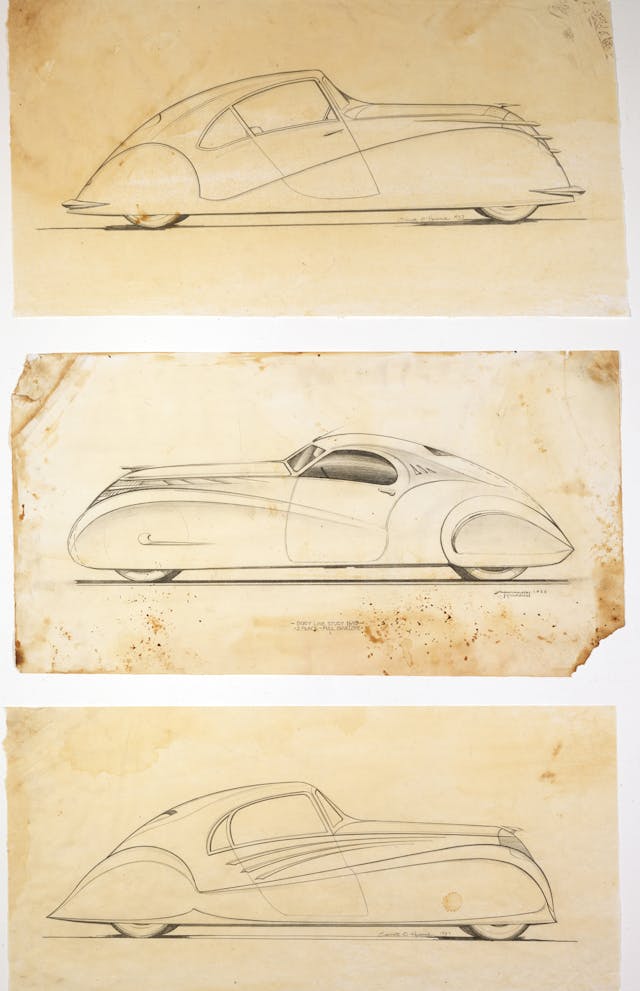

With permission from the elderly woman who owned the barn, they searched a trunk found therein. The drawings, letters, and photos it contained, most yellowed and moisture-stained from decades in storage, depicted a car with flowing aerodynamic lines reminiscent of the flamboyant Art Deco creations by France’s Figoni & Falaschi coachworks.

The trunk’s contents also provided evidence of a bizarre saga to rival the most sordid elements of the Real Housewives cable TV franchise. The wealthy Frenchman who had commissioned the car, Gui de LaRouche, had named the Coupé Simone for his lover. The project took the small coachbuilder nearly three years to complete. Its proprietors, Emmett Hardnock and Armand Minasian of Williamsport, Pennsylvania, planned to debut the car at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. There, its futuristic look would have fit perfectly with the sprawling event’s theme.

Instead, things took a sinister detour.

Love and war

Prior to the World’s Fair, de LaRouche demanded delivery of the Coupé Simone in France. The timing could not have been worse. Hardnock traveled by steamship to accompany the car and collect final payment. Before the ship docked, though, Germany invaded France, plunging Europe into chaos.

Hardnock made it to Paris, nevertheless facing a conflict of a different sort. It seemed that de LaRouche’s assistant, Antoine St. Claire, who had been overseeing the Coupé Simone project for him, had also been having an affair with his lady. Taking revenge, the jealous de LaRouche forged papers implicating St. Claire and Simone as traitors to France. He refused to make final payment to Hardnock, who then teamed up with St. Claire to steal back the car.

In a telegram to Minasian in America, Hardnock explained that he would attempt to transport the Duesenberg to Prague, Czechoslovakia, where relatives could hide it. And then both he and the car went missing. Minasian booked passage to France to search for both, but he, too, never returned home.

Engrossed by the story, the two Franklin Mint designers made a fifth-scale fiberglass model based on the drawings they’d discovered. They then made the model the centerpiece for an elaborate exhibit at the Franklin Mint Museum in Philadelphia, featuring many of the materials from the trunk. Impressed by the presentation, the company’s owners decided to make the mysterious Coupé Simone their next Duesenberg 1/24-scale model in 1998.

More fascinating than fiction

If you remember that Automobile article, you might also remember the disclaimer at the end: The car and the entire story behind it were made up.

It was neither a hoax nor an April Fool’s prank, though. Rather, the two Franklin Mint design directors, the very real Roger Hardnock and Raffi Minasian, created the melodramatic story and all the artifacts that supported it as an exercise to inspire their design process.

In the accompanying interview (scroll down below), Minasian explains to Hagerty how the process (and fun) of building the backstory and creating the “documentation” immersed him and Hardnock into the period. The exercise, he said, allowed them to envision an over-the-top, futuristic-looking car from the viewpoint of designers in the late Thirties, rather than as designers in the 1990s looking backward.

“The Coupé Simone [model] sold better than Franklin Mint’s two previous real Duesenberg models,” Minasian recalled. “We’d speculated that the story was almost more important than the actual vehicle.”

***

Back to reality: Duesenberg built the glorious Model J, SJ, and JN chassis from 1929 until 1935 (481 total), but orders for cars came in slowly during the Great Depression. Three dozen supercharged “SJ” examples were made.

When buying a Duesenberg, the customer bought a chassis with powertrain for $9500 (about $207,000 today!) and then selected a coachbuilder to construct a body. The total price would go into the high teens or even higher in some cases. A 1937 Duesenberg Model J Convertible Berline bodied by Rollston in New York City is considered the final car completed and sold while Duesenberg was still operational. A couple leftover chassis received bodies by 1940.

While the Emmett-Armand Coachworks may be imaginary, Duesenberg itself engaged in a bit of fiction with LaGrande, its in-house “coachbuilder.” Contract body makers built the LaGrande bodies according to designs from Gordon Buehrig, Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg’s artistic maestro who also created the landmark Auburn 851/852 Speedster and the Cord 810/812. Most LaGrande bodies were built by the Union City Body Company in Union City, Indiana, including the original body of Leno’s 1931 coupe. The company continued as a commercial truck and bus body maker that Utilimaster absorbed in 2005.

The LaGrande name itself was a sneaky play on LeBaron—at the time perhaps America’s most renowned designer and coachbuilder—which created some memorable Duesenberg Model J bodies.

Realizing the Coupé Simone

The curvy Art Deco Coupé Simone would have been a daunting coachbuilding project even in the late 1930s, a time when the craft was still thriving. Today, Martin and his Iconic Rod and Custom Shop plan to apply traditional coachbuilding methods to produce the body, albeit with a little help from digital technology. Martin recently constructed a 1963 Ferrari 250 GTO replica using these very techniques, building its body by forming aluminum over a wooden buck.

“I sold that one but have enough parts to do another,” he told Hagerty.

Martin’s approach to the Coupé Simone will be comparable but will not have a Chevy LS engine, as the 250 GTO replica had. (We’ll get to the powertrain in a moment.)

Minasian is consulting on Martin’s project, including providing original drawings and models from the Franklin Mint. Using 3D scanning on a scale model of the Coupé Simone yielded full-size two-dimensional patterns in sections. Martin will use those to make a wire frame out of half-inch hollow tubing and build the aluminum body around that.

The Coupé Simone will be a very large car, though not quite as large as the biggest Duesenbergs. Most of the three-dozen SJs were built on a 142-inch wheelbase, but a few were on the company’s 153.5-inch wheelbase. Two special models, known as SSJs, used a 125-inch chassis.

By necessity, the full-size Coupé Simone will be more of a 9/10-scale car. As Minasian explains: “The digitized scale does not translate exactly to full size. It gets close, but you must do some finessing, some adjusting, because proportions sometimes get exaggerated when you enlarge them. And so, frontal overhang, vehicle height, some of the general characteristics including the length of the wheelbase, are different.”

The Coupé Simone story states the imaginary car was built on a 153.5-inch wheelbase SJ chassis, so the 10 percent reduction yields a 138-inch wheelbase for Martin’s realization.

“We will probably raise the height a couple of inches for practicality, but the overall look won’t change,” Minasian explained.

Martin will build the Coupé Simone in its Midnight Ghost spec, with a two-tone silver and dark gray exterior and tan leather interior.

“We’ll make a ladder frame chassis and then use subframe sections for the engine cradle and rear suspension,” he said. “We’re talking with a couple of companies about suspension ideas.”

The Coupé Simone will roll on modern rubber, possibly wrapped around Dayton wire wheels, which some original Duesenbergs used. When Martin spoke with Hagerty in early February, he said he would use a straight-eight or V-12 from the period, possibly fitting the engine with a McCulloch supercharger.

“I’m going to leave that as a surprise for the moment,” he said.

Of note, Auburn offered cars with a 6.4-liter V-12 engine in the Thirties. (Leno owns one of those, too.) Duesenberg also built a 1936 prototype called the “Gentleman’s Roadster,” using the Auburn V-12 built by Lycoming. The Auburn engine later became the basis for a larger-displacement version used in American LaFrance fire trucks.

In keeping with the spirit of the period, the Coupé Simone will use a modern five- or six-speed manual transmission. Martin has been through some arduous builds, so he expects to have to overcome obstacles along the way.

“There are always challenges,” he said.

He has a video crew documenting the whole build, so we’ll all get to witness how an imaginary “lost” Duesenberg becomes a real, drivable car in the 21st century.

***

Interview with Raffi Minasian

Raffi Minasian, one of the two designers that created the Coupé Simone, spoke with Hagerty about the fictional backstory that inspired his Roger Hardnock’s beloved design. A designer, professor, and journalist, Minasian is also a Pebble Beach Concours d’ Elegance judge and a frequent speaker and panelist at automotive conferences. Over the past 40 years, he has designed and built several award-winning show cars, hundreds of scale model cars, thousands of automotive accessory parts, and worked in partnership with shops building custom cars and hot rods and restoring concours-winning vehicles. He co-hosts the weekly Clutch Radio with Dan Rosenberg podcast, consults on restoration projects, and performs inspections and valuations. Minasian served for six years on the board of the Hagerty Collectors Foundation, which became the Hagerty Education Fund and now the RPM Foundation.

Hagerty: The first Franklin Mint Coupé Simone model came out a quarter-century ago. Did you ever envision someone building a full-scale, drivable version?

RM: Roger Hardnock and I had always imagined that somebody might approach us to build it. Over the years, many have asked if they could. The answer was always yes, but only depending on what level of build they were planning. Our vision has always been that it be a steel or aluminum-bodied car with the right level of fit and finish and execution, not a fiberglass body on top of a production chassis.

Hagerty: How did you connect with Greg Martin’s Iconic Rod and Custom shop?

RM: Greg contacted me in spring 2022. After some conversations about what was possible, it became clear that he had both the passion and skills to pull it off. This will be his car.

Hagerty: Will you be involved the build?

RM: I’ve been working with Greg, and that will continue. I’ve sent him drawings and specs. We’ve discussed quite a bit about the construction details. I’ve built cars myself, so I’m no stranger to that aspect. I’ve done quite a bit of work with other shops, building hot rods and customs, and I do a lot of forensic restoration on vehicles that have lost their original body work.

Hagerty: Which came first, the Coupé Simone’s design or its fictitious backstory?

RM: Designers tend to think about the future and project what the world is going to be like 5, 10, 20 years from now. We thought, why not apply those principles to the past? Before we designed the Coupé Simone, we immersed ourselves in that period, what was going on with car design, what was happening culturally, and let the design of the vehicle emerge from that mindset. Then it was just a matter of weaving the speculation into the history, which we thought was a tremendous amount of fun. That was the main driver behind it.

Hagerty: How did you set the stage for a late-’30s setting?

RM: By drawing in the style of the period and aging our drawings. We spent quite a bit of time trying to figure out how to make a drawing look old and wrinkled. When you see what your drawing looks like, what you’ve drawn in contemporary times, and you’ve applied a history to it, you’ve given it a visual identity that creates a kind of romanticism. Ultimately, that’s what people felt when they saw it. They wanted to believe the story. Like a good movie, it pulls you in.

Hagerty: If you had not created the dramatic backstory, do you think you could have designed Coupé Simone?

RM: I don’t think so. I think the idea behind the creation of it, the story and the atmosphere for it, were integral to the effort. It’s not the average person who spends that kind of money on something as astonishing as a car of this sort. The background, the history, the hubris of it must be there to give a sense of who this person is.

Hagerty: There were plenty of colorful, wealthy people who commissioned extravagant cars for themselves in the Thirties. How did you create a story that seemed relatable to a wider audience?

RM: The person who commissions it is a wealthy cosmetics entrepreneur. And his love interest is someone he cannot have. So, he names the car “Simone” for her. It’s kind of a play on the irony. It’s the thing he can’t have, and it’s a car that doesn’t exist, much like her returned affections for him. The car gets lost in Europe in the delivery. Both partners in the coachworks are also lost. All that loss tugs on the heartstrings of what people connect to when they hear personal, historic stories.

Hagerty: Franklin Mint ultimately made two different versions of the Coupé Simone, and Greg is building the second version, the 10th anniversary model, which has a different color scheme than the first. How did that come about?

RM: After I left Franklin Mint, I continued as a consultant for them. When they asked me to create a 10-year anniversary version, I went back to our original story, which described an initial version of the car that de LaRouche, the cosmetic executive, rejected. That was done as a supercharged car with dark gray and silver exterior and a tan interior. In the story, de LaRouche visits the coachbuilders in Green Brier, but he arrives late because of train delays. So he’s taken for a frightening ride in the car in the middle of the night. And he tells them, “It’s too fast, too frightening, and too menacing-looking. You must change it.”

Hagerty: And that becomes a plot twist in the story?

RM: The coachbuilders then changed to a non-supercharged engine and chose a color scheme based on the baskets of green apples and lilacs that a local young girl would sometimes bring to the shop. There’s a sort of two-tone in lilac flowers, which inspires the car’s main colors. And there’s kind of a light fading green stripe representing the apples.

That revised version becomes de LaRouche’s car and the original Franklin Mint model. The version he rejected, which we called the Midnight Ghost, then justifies the 10-year anniversary car. Franklin Mint offered that one as a limited-edition of 1500. I signed a plaque for the bottom of it, and it sold out within weeks. That’s the car Greg is building.

Hagerty: When you previewed the model and exhibit at the Franklin Mint Museum, how did the visitors and media respond to the story of a previously unknown Duesenberg?

RM: We didn’t tell anybody that it was real or not real, but we did put a small placard in a corner that explained it. Probably nobody read it, though. A couple of people who signed the guestbook said that they remembered their fathers talking about seeing the car at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Another wrote that he believed he knew where the car was in France.

Hagerty: How did the Automobile story happen?

RM: [Automobile art director] Larry Crane told us Automobile was going to give the story six color pages. He said he loved finding out about it and getting caught up in the story before realizing it was fictitious. He said he wrestled with revealing that it wasn’t real, to see what letters readers might send, but ultimately decided to tell the truth at the end of the story.

Hagerty: This fictitious car got the blessing of the Duesenberg community?

RM: The Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Museum asked us to provide information on the families involved to put into their archive, which we provided along with the explanation that the story was fictional. We were connected with people in the Duesenberg community, so we contacted Randy Ema, who owns the Duesenberg brand. He was excited about the project and provided us with a chassis number for a Duesenberg that was known to no longer exist.

Hagerty: Despite the Automobile story and other reports revealing the truth, the fiction seems to still live on …

RM: Even today, I see Coupé Simone images on social media on a regular basis from people posting photos as though it’s historically accurate. Some have put the Coupé Simone on lists of beautiful cars from the Art Deco period.

Hagerty: What kind of punctuation mark would you say building a real Coupé Simone puts on the story?

RM: When Greg’s build is completed, the Coupé Simone story will be told, and at what point then is it no longer not real? Because if you now have the artifact and you have all the story, it becomes something in and of itself. Ultimately, what we’re really trying to do for people is engage their creativity, their imaginations, and inspire them to think a little bit differently about vintage automobiles and the emotional connections they inspire.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

A shop in Williamsport is going to do this?! That’s awesome!

I’ve had a bit of a soft spot for the city: my alma-mater is there, though I haven’t been happy with them since 2019.

Still had plenty of great memories there! The history alone is pretty cool.

Can’t express how wonderful this tale and project make me feel. My thanks to all involved, and especially to Hagerty for delivering the story to me.

Great project, can’t wait to see it built (hopefully in person someday) but it’s a shame they didn’t go for the purple.

If I’m interpreting the story correctly, a mythical car was elaborately & painstakingly created so that a model of it could be sold ? Seems dishonest to me that the story was originally presented as factual, and documentation was created out of thin air to legitimize it. There were a few “gut” clues early in reading this article that seem too coincidental, but I’m left with the lingering aroma of an elaborate fraud perpetrated on the folks who bought into Franklin Mint’s story and bought the model…

A reasonable statement if you were unaware of all the indications that stated the entire project was a fictional adventure into automobile design. All publications even the original museum display were accompanied by explanation disclaimers. We consistently presented it as a phantom. Few people go to the movies thinking everything they see is factual. Even stories that are based on true events take liberties. We thought it would be fun to explore historical fiction within the car community.

The story was not created to build a model of it. Roger and I created it on our own time, at our mutual design studios, over a year and then exhibited it at the Franklin Mint Museum along with our design and illustration work for other car companies from our mutual careers. The owners of the Mint liked it so much they asked to do it as a scale model. So we did.

In the nearly 30 years since we conceived of the project, it’s been a fun, engaging, and ongoing conversation on the enjoyment we experience while stretching creative boundaries.

Now that’s an article! Loved the research and details.

Good job!

Do some more like that rather than telling me how to winterize a car.

Cheers

Kent.hooey@pembinahills.ca

Fantastic story! I was hooked from the beginning. Smiled the whole time and even laughed out loud.

We laughed many times while we were making the clay model of this car and doing the drawings one by one. Joy is a big part of creative expression. It’s great to know others felt that as well. Thank you.

Thank You very much. A true learning experience.

Very neat story. The car looks interesting.

I’m not a big Batman fan, but it kinda looks like the Batmobile in the animated series and the 2004 Batman.

Just like l’ont, I would of like them to build the purple one as the black one is just too gangster looking. I guest it’ll be cool any way they build it!!!

Beautiful. Mesmerizing. I’m excited to see it become real. Now I have to go find a scale model…

Weren’t American LaFrance firetucks famously powered by an engine originally designed and used by Pierce Arrow rather than Auburn?

Seagraves through 1970 used the Pierce-Arrow V-12, bumped from 462 to 530-

ci, through 1959 Pierce’s nine-mained 1933-38 straight eight, retaining the 8’s stock 385-ci, it and the V-12 having hydraulic valve lifters, a 1933 Pierce invention.

American LaFrance 500-, 750-and 1,000-gpm pumpers used a 7.2:1 compression, 526-ci twin-ignition version of the 392-ci, 5.7:1 compression 1931-33 Auburn V-12 through 1962. All three engines were given twin ignition, mandatory in emergency equipment.

Years ago, the Imperial Palace in Las Vegas had an impressive number of Dueseys in their upstairs “museum,”

and from the description of the rebody of the ’31 La Grande Coupe, I would surmise that it was one of the cars in the exhibit. “Hideoux, bulbous” exactly described it. It was if it was made from an overgrown pumpkin. Needless to say, it stood out like the proverbial “sore thumb” amidst the beauty of the other “real”

bodied Deusenbergs. Regarding this article’s fabricated Deusenberg, sorry but it really doesn’t do anything for me. I would be more interested in the Buggatti that was built by “The Guild” in Canada. Twas a real car, also a “stunner”.

Truly two “con-artists” of the highest order; so a well deserved homage to their artistry.

The ’30s rife with nascent streamlining. The above looks the Cord-based ’38 Phantom Corsair, designed by the 22-year-old heir to the Heinz 57 fortune, the effort built by Bohman & Schwartz in Pasadena, where Rusty Heinz lived with his aunt, who paid for the project.

Packard’s four ’34 Model 1108 LeBaron sport coupes arguably came out a little better.

As those remembering the times and cars fade, perspective and reality join them. Regardless how many casino owners, pizza chain magnates, comics own them, what does it tell you about Duesenbergs that it took nine years and several iterations to sell 480 of them, all chassis built 1928-29? Obsolete two years after their introduction, all with crash boxes despite other luxe cars quickly adopting Cadillac’s 1929 Synchro-Mesh, with front-end vibration periods, which cursed all ultra-long wheelbase cars at this time, cart-springing at the end of its tether, the long timing chain stretching, upsetting valve timing at high rpm, according to Richard Hough, in his masterful A History of the World’s Sports Cars, introductions by W. O. Bentley and S. C. H. Davis.

Of course Duesenbergs were impressive, and on a long, straight road, unpassable. For their inflated price, they should’ve been, costing quintuple as much as a lovelier 1931-33 Chrysler Imperial, and you’ll note how rarely the latter for sale; in good tune, only ten mph slower than most Js in road trim, according to historian/engineer/machinist Maurice Hendry, who also observed a Marmon 16 would out accelerate a J to 70.

None of the above takes away from Greg Martin’s skill and craftsmanship.