When a mysterious American recluse hoarded gold, airplanes—and fabulous cars

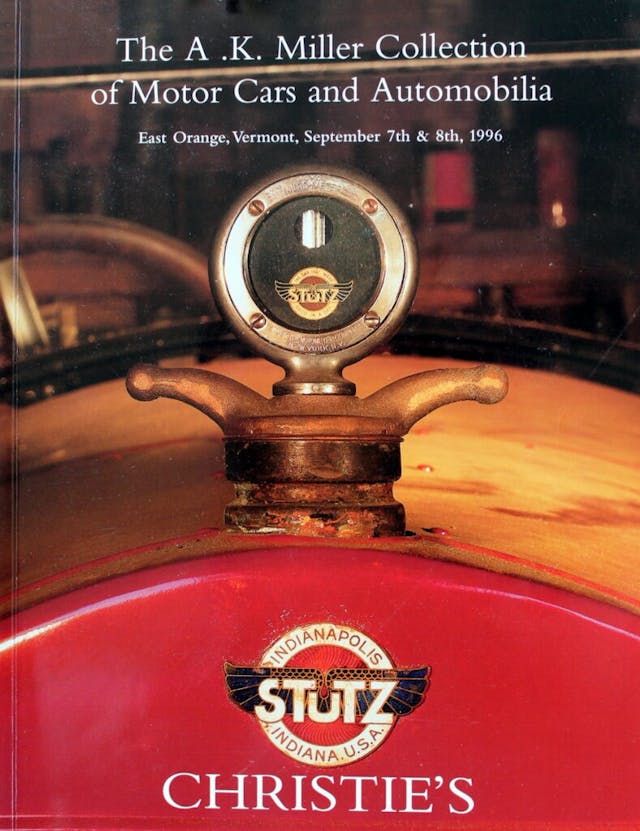

Wags billed it as “the opening of King Stutz’s tomb.” Held over a weekend in early September of 1996, the Christie’s auction comprised some 287 lots. Thirty-five were vintage Stutz automobiles in various states of disrepair. There were other rare prewar cars too, a Locomobile and a Rolls-Royce and a Stanley Steamer and more besides. Drawn by the tales of hidden gold bullion, crowds flocked to see one of the greatest barn finds ever uncovered. All of it had belonged to a recluse that everyone thought a pauper.

Alexander Kennedy Miller died in 1993, his wife Imogene three years later. After each had passed, a local church took up collection on their behalf, so the pair might be respectfully buried. No money had been set aside by the couple, and while the farm they had owned stretched across several acres in rural Vermont, the property was a ramshackle collection of dilapidated buildings. The place barely had electricity, all heat was by wood-burning stove, and the plumbing was ancient. A rotting Volkswagen or two sat in the front yard.

The couple were known to be friendly enough with a few locals, but outsiders found them withdrawn, stiff, and reserved. And outsiders would come, every so often, hoping for a glimpse at the Millers’ rumored treasures, hidden from sight for decades.

A.K. Miller, as he was known, was born into wealth in 1906. The only son of a New York stockbroker, he received a fine education and enrolled in the mechanical engineering program at Rutgers University. While still in high school, he had the funds to buy a Stutz automobile, a 1917 Bulldog, the first of many he would own. He kept the car until his death.

Stutz is perhaps not a familiar name to modern ears, but the marque is significant. Considered by many to be America’s first sports car, Stutzes were at their peak found everywhere from the Indy 500 to the podium at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

In fact, the Indy 500 was the birthplace of the marque. Harry C. Stutz was one of many mechanical geniuses at the dawn of the 20th century, and the first car he ever built was entered at the first running of the 500, in 1911. It placed eleventh that year, out of the prize money, but even finishing was a victory in those days, and almost half the field did not. Mr. Stutz took up the slogan, “The car that made good in a day,” then set about building road cars.

Stutz production ran until 1935. They were quick and luxurious machines with underslung chassis, given names like Bearcat and Blackhawk. The rare supercharged models were often judged to be faster than contemporary Bentleys.

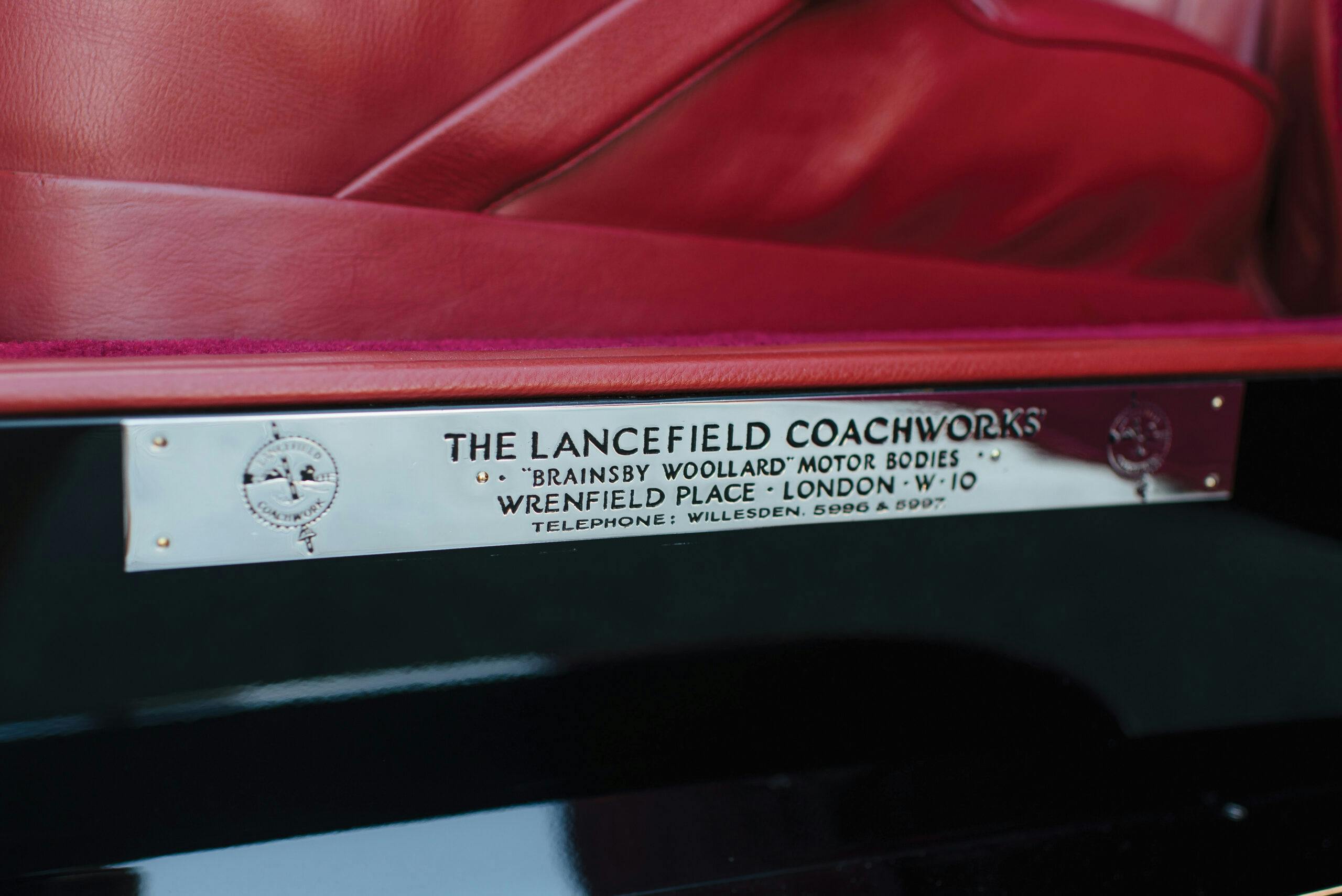

One of those forced-induction machines, a 1929 Stutz Model M Supercharged with coachwork by Lancefield of London, eventually found its way to the A.K. Miller collection. Bought for $151,000 at that 1996 Christie’s sale, it was later restored. Ten years later, in an auction at Michigan’s Meadow Brook Concours, it sold for $715,000.

Miller himself probably paid a pittance for the car. He began collecting Stutzes in the late 1920s, snapping up many of them at bankruptcy sales or estate auctions. Many of those cars would be carefully brought home and then parked under a lean-to or in a barn, not to see the light of day for decades hence.

Adding further quirkiness to the tale, Miller was a pilot and collected aircraft of all sorts. In the mid-1930s he founded Miller’s Flying Service service, right around the time United States Air Mail was embroiled in a corruption scandal. It was a time when air travel was something of a Wild West for entrepreneurs, with heavy subsidies and much profit to be made.

Miller delivered the mail by autogyro—a helicopter-airplane mashup contraption that seems outlandish today but was relatively common at the time. When he retired from that work, he tucked the autogyro away in a barn as well. Later, he flew as a transport pilot for the Royal Canadian Air Force (he was over the United States age limit for military pilots), achieving the rank of captain. After World War II, he settled down with Imogene, who he married in 1941.

Early pictures of the couple twinkle with Gatsby-like glamour. But with time, the Millers began to withdraw from the social order, almost as if they distrusted it. In the days before Social Security numbers, they probably found it relatively easy to fade into the country’s background. Their money was not kept in banks, but in coins and bullion, or stocks and bonds. Nobody knew how much the Millers had squirreled away. Eventually, most folks forgot they had anything.

A.K. Miller was not unknown in the Stutz community. People remarked on his odd personality, but his vast knowledge of the brand was perhaps unequaled. In a letter to one petitioner, Miller notes that Stutz windshield stanchions differed between 1929–1930 models and those built in 1931. As it happened, he added in the letter, he had the correct parts on hand, for a price.

Those parts were likely manufactured by Miller himself. The note was typed in red—he had a habit of using the red “highlight” ribbon of a typewriter long after the ribbon’s primary black ink had run out.

Most people who had financial dealings with Miller found him frustratingly parsimonious, or at least quite odd. But there are a few stories from Vermont locals that depict him as all too happy to show off his collection. The Millers lived at a level of thrift that seems extreme, but then, they had each weathered uncertain times, a Depression and two World Wars. Keeping a low profile also made it easier to avoid taxes, which A.K. Miller never paid.

This last habit was the eventual undoing of Miller’s Stutz hoard. At 87 years old, he fell off his roof while repairing a storm window and died. Imogene passed three years later from heart attack. As they had no heirs, local officials moved in to secure the estate. When a sheriff found a stack of bonds taped behind a mirror, it was like kicking over a hornet’s nest.

The Miller farm was soon ringed in police tape. When the Internal Revenue Service realized that millions were owed in back taxes, the agency began exploring just what had been hidden. What they found was staggering: A million dollars in gold bullion. Nearly the same amount in stocks and bonds. And, of course, those dozens of Stutzes.

That Christie’s automotive auction netted about $2 million, and many of the cars are still in the market today. They were largely in sad shape when recovered, but the sheer number of parts and accessories that Miller had kept helped many of the cars be restored. One, a 1918 Bearcat roadster, is currently owned by Jay Leno.

The eccentric and reclusive life here may seem sad, glory faded shabby. But it’s worth remembering that Miller’s obsessive pack-rat mentality did result in many spectacular cars being saved from the 1930s to the 1950s. In that press-forward and often resource-thin time, even something as exotic as a Stutz would have been seen as merely an old car, fit only for the crusher.

If Miller’s collecting was a bit selfish in life, it still preserved much for the future. Even if the taxman did end up getting his share.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

As the saying goes, the only certainties are death and taxes. Interesting story, thanks for sharing it.

Yes, an interesting story and if memory serves me right the now no longer published Automobile Quarterly magazine had a rather good article about this as well and it included some good photos. …think I’ll have to go check my collection of Automobile Quarterlys and re read the article…

A friend has an early (14 or 16) Bearcat, cosmetically unrestored from its years with the Millers.

We drove around the Indy infield with it during a IMS centennial car show and Stutz Club meet back in 2011.

Still one of the motoring highlights of my life.

That you, John Stutzman?

“Nutzy Stutzy’s” Lancefield Coupe (s/n 31312) has sold four times after the 1996 auction:

RM’s NY Auto Salon auction in 2000 after its restoration for $316,800;

RM Meadow Brook in 2006 for $715,000

RM Monterey in 2010 for $660,000 and

RM Amelia in 2017 for $1,705,000.

At the Auto Salon and Monterey it was cataloged as a 1930, same as at Christie’s in 1996, which may be why those two transactions were overlooked (except in the photo caption.)

They never paid taxes and then the IRS picked over the carcass like vultures. Not surprising on both ends.