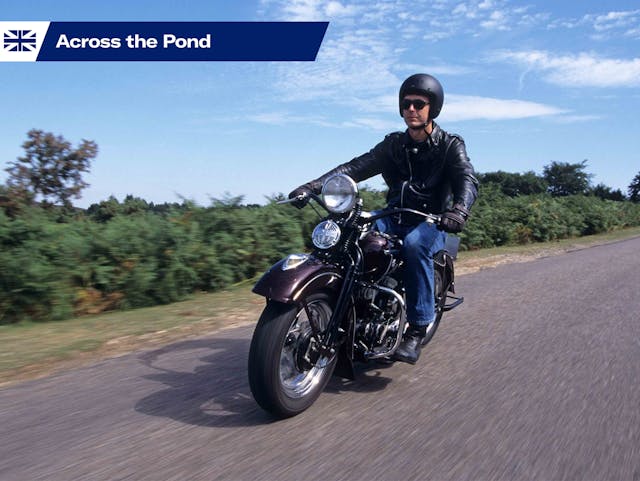

A wartime relic, Harley Davidson’s WL45 calls for a cool head

In recent months the United States military has supplied a variety of weapons and equipment to the Ukrainian war effort. Motorbikes have not featured on the list, but things were very different 70 years ago during World War II, when the two-wheeled equivalent of the Jeep was Harley-Davidson’s WLA, a 742cc V-twin that was derived from a popular civilian model, the WL45.

The WLA military bike—and the closely related WLC, built for Canadian troops—entered production in 1942 and were also supplied to forces including those of Britain, the USSR, and even China. During the conflict Harley built an estimated 90,000 of the robust V-twins, many of which were later converted to civilian specification by removal of parts including the blackout lights and leather gun-scabbard.

The 45, named after its engine capacity in cubic inches, dated back to 1928 and was a simple “side-valve” V-twin with cylinders set at Harley’s traditional 45-degree angle. In 1937 it was revamped to create the W45, notably with a new lubrication system that replaced the crude total-loss design. Harley’s L was factory code for high performance but, despite its increased compression ratio, the WL produced only about 24 hp.

Harley recommenced production after the war with few updates, so the WL still had a simple three-speed gearbox, with a hand lever and foot-operated clutch. Its chassis was similarly old-school, featuring springer front forks and no rear suspension. The “hard-tail” Harley relied on its sprung saddle and fat rear tire to isolate its rider from bumps.

This neatly restored bike was built in 1949, the year the WL’s front suspension was updated with a new Girdraulic damping system, in place of the simple friction damper used previously. The improved control this gave was doubtless welcomed by riders at the time, but riding the WL confirms that any resemblance to the traditionally styled V-twins produced in Milwaukee these days is purely visual.

A modern Harley fires up with a touch of its starter button, clunks into gear with a tap of the left boot, and pulls away as easily as any new bike. Not so the WL. When cold, it required numerous jabs at the kick-starter, some with full choke and others with the lever half-on, before it finally came to life with a low-pitched chuffing through its single silencer.

That was the easy bit: The WL’s foot-operated clutch ensured that years of motorcycling experience gave poor preparation for riding this one. After adjusting the ignition advance-retard lever on the left handlebar, I engaged the clutch with a press of my left boot, then selected first gear by pulling back on the lever to the left of the gas tank. I dialed in a few revs with the conventionally placed twist-grip, then slowly released the clutch by pushing down with my left heel, until the Harley started creeping forward …

And suddenly I was away, clutch kicked fully home and throttle wound back further, changing into second with another shuffle of my left foot and a firm push forward of the gear lever. The revs rose slowly—I reached for the lever again to change into top. By now the WL was doing about 50 mph, I had both hands back on the wide bars and was bouncing gently up and down on the sprung saddle as the Harley chugged along, feeling smooth and stable.

Riding an old foot-clutch bike like this certainly takes some getting used to, and the learning is best done far from other vehicles. After a morning spent pottering along some deserted Hampshire lanes, I was sufficiently confident to pull away, change gear, and stop without worries. But I wouldn’t have fancied venturing into town without more practice.

The clutch was the most difficult part. Especially when I needed to pull away and turn left at the same time—for example, when leaving a T-junction. Provided I remained positive, it was okay. But if for any reason I’d changed my mind while pulling away and leaning to the left, I’d have been in trouble; simultaneously disengaging the clutch and putting my left foot on the ground would have been impossible.

Once under way, things were much more normal. The short first gear meant that the change up to second was best accomplished almost immediately, and the WL was torquey enough to pull fairly smoothly, though very gently, in third (top) from as little as 30 mph. So at that speed I could select top with another push of the lever, then forget about the clutch and enjoy the ride.

More aggression was needed to make quick progress because, despite its respectable engine capacity and abundant charisma, a Harley 45 is not a fast motorcycle. The WL cruised happily with 60 mph showing on its big, tank-mounted speedometer, feeling pleasantly smooth and relaxed, but by 65 mph was feeling breathless and approaching its limit.

That’s not surprising, because W-series bikes were never noted for their speed. Indian’s rival, 45-cubic-inch V-twins were faster and lighter. The WL’s chassis also received criticism when new, but I was relieved to find that this bike’s relatively modern tires helped give better handling than it would have had back then.

In fact the WL steered nicely, helped by its wide handlebars. Considering their age, the forks did a good job of soaking up bumps. Even the unsprung rear end coped surprisingly well. It was a strange sensation to rock gently up and down in the saddle, conscious that the Harley was bucking beneath me—though on one occasion I was jolted back to reality when the seat spring bottomed painfully on a pothole.

This bike’s brakes are not its best feature. The feeble front drum, in particular, makes even the WL’s modest performance seem plenty. The larger rear brake had more power, but the need to lift my right foot off the board to reach the lever increased stopping distance and reduced control.

One thing the WL does have going for it, which helped make its reputation, is reliability. The Harley might not have been as quick as Indian’s 45s, but it was far more robust—which of course had been a vital attribute when it was modified to become the WLA and put to the ultimate test.

Despite its ability to carry a rifle or machine gun (plus a box of ammunition on the sturdy rear rack) the WLA was generally used for courier work, scouting, and transportation, rather than in combat. But it was popular with its riders, served with distinction throughout, and earned the nickname “Liberator” during the Allied advance in 1945.

After WWII, many returning U.S. servicemen bought surplus WLAs at bargain prices. Some “bobbed” or “chopped” them with cut-down fenders or longer forks, putting the 45 at the heart of the booming biker scene. By Harley-Davidson standards the WL was not particularly large or powerful, but few Milwaukee models have been as versatile—or as widely admired.

***

1949 Harley-Davidson WL45

Highs: The challenge and V-twin character

Lows: Traffic, until you’ve mastered the clutch

Takeaway: It has style and a unique place in history

—

Price: Project, $12,400; nice ride, $16,900; showing off, $35,800

Engine: Air-cooled side-valve V-twin

Capacity: 742 cc

Maximum power: 24 hp @ 4000rpm

Weight: 573 pounds without fluids

Top speed: 65 mph

the WL’s foot operated clutch was known as a suicide clutch in the US for good reason. Wish I had kept the one I briefly owned.

Love this post because I know how he feels bouncing up and down on that pogo there’s nothing like it it is a real experience to ride a real Harley I will continue to ride my 42 WLC as long as I can see above the dirt LOL