How Porsche’s secret 989 sedan went from savior to failure

Last year, four-door sedans and SUVs represented 80 percent of Porsche’s sales. Just take a moment to let that sink in. The German company’s scope has expanded so much that the 911 and 718 Boxster/Cayman sports cars—Porsche’s core product lines—were a mere one-fifth of its output in 2021. Even the Taycan EV outsold the 911.

Enthusiasts love, and sometimes love to hate, Porsche for its sports cars, but even as far back as the ’80s the Stuttgart company knew that two-door vehicles were a small fraction of the global market. We can’t really begrudge Porsche for changing direction—in reality, it has had little choice in the matter. What’s perhaps surprising is just how long it took to get there in the first place.

Back in 1988, Porsche made just 31,362 cars, generating a paltry $13.7 million in profit—well under a single percent margin, at the time. No business can survive on that. The front-engined 944 and 928 were selling slowly and the 911, in its 964 iteration, was aging fast. After all, it was using a body structure that dated back to 1966.

Enter Ulrich Bez, as Porsche’s new member of the board of research, engineering, and motorsport. To survive, Porsche needed new product, and fast. The engineer joined the ailing company from BMW Technik, a legally separate entity from the BMW parent company.

Technik’s role had been to design and engineer vehicles in a team environment without being shackled by the processes of creating production cars. That hadn’t stopped one slipping under the noses of the accountants and making it to the road, though: the radical Z1 roadster, created by Technik’s design team led by Harm Lagaay, the designer behind the Sierra RS Cosworth who had started his career earlier at Porsche. Bez was a perfect fit as Porsche’s new engineering boss.

Soon after Bez settled into his new role at Porsche, he encouraged Lagaay to follow him to the Dutch designer’s former employer, in late 1989. “Things were worse than I realized,” recalls Lagaay, “The model range was aging and the first thing I did was to see about quickly refreshing the 911.” That quick rejuvenation was the 993-generation car that 911 enthusiasts now hold dear to their hearts. The last air-cooled version cleaned up the fussiness that had so aged the 964.

It could be no more than a stopgap 911, but it was enough. The bigger task was what to do with the four-cylinder 944 and V-8-powered 928. The smaller car still brought in some volume, but the 5.0-liter 2+2 was selling in tiny numbers. With less than 1000 sales each year, it made no sense to directly replace the 928.

Bez rightly decided to take a punt. The 993 could tide things over on the sports-car front, and the 944 was given a low-cost facelift as the 968. This left the thorny issue of replacing the V-8. The 928, originally conceived as a 911 replacement, represented the worst of both worlds; too big on the outside for 911 buyers and too small inside to serve as a proper four-seater. Bez was all too familiar with the BMW M5 from his days at Porsche and the four-door super-saloon’s fat profit margin.

The idea for the 989 was obvious: a new Porsche, with an eight-cylinder engine featuring far more power than BMW Motorsport’s six.

Porsche might have been on its knees, financially, but it had a talented design leader in Lagaay and a visionary engineering manager in Bez. What it now lacked was the product-planning expertise that ensured a vehicle’s concept delivered against the market’s needs.

The M5 outsold the 928 four-to-one, but even so BMW shifted just 4000 M5s per year. What BMW could do, that Porsche could not, was amortise the super-saloon’s costs over the far larger number of regular 5 Series it churned out every day.

Would the sums add up for the 989?

There is a theory that the first mover establishes the market and—as Blackberry, then Apple, found—a second newcomer perfects their product and mops up. Such an evolution is fine in the world of consumer goods, but Porsche needed to drastically outsell the M5; to make the numbers stack up, it would have to sell roughly one hundred thousand 989s over the car’s life to recoup tooling costs. It was a big stretch for the financially strained small company.

One obvious way to keep costs under control was the most expensive component, the engine. Porsche had tooled up for the V-8 powering the 928, but at around $7000 per motor, it was a hugely expensive element to make in-house.

A far smarter route was to buy in a V-8 block and rework it with new heads and ancillaries, just as Porsche had done with the 924’s EA831 engine that first saw service in the Audi 100. However, purists sneered that it was merely a VW van engine, and Stuttgart replaced it with a genuine Porsche unit derived from the 928’s V-8 when the 944 arrived.

But needs must, and Audi’s 3.7 liter V-8 from the A8 was a fine motor that Porsche could fettle for the 989. There was the possibility, assuming Porsche survived into the late-’90s, that the 989 could later be updated with a Porsche-designed engine that could also serve duty in whatever replaced the 911.

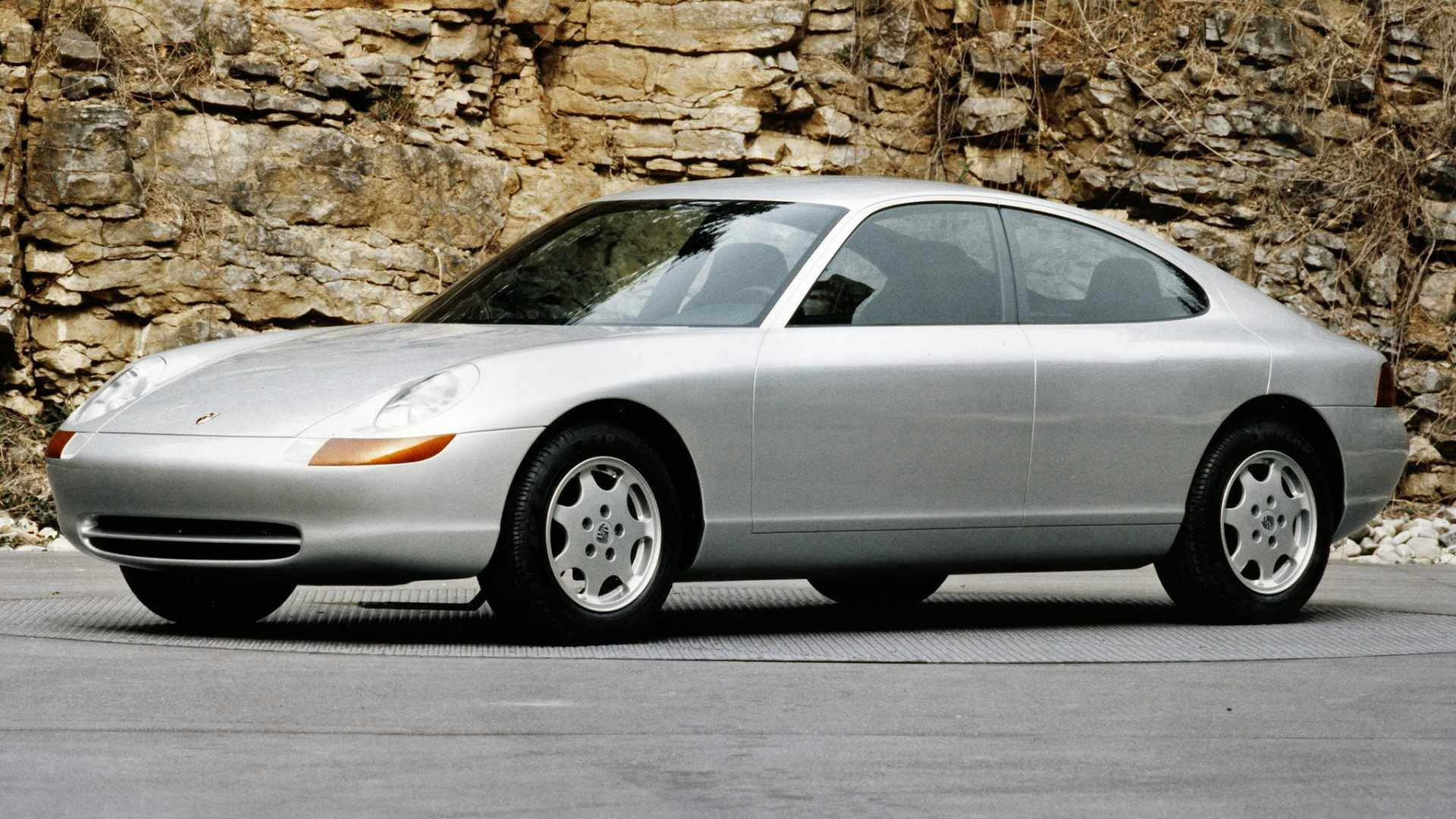

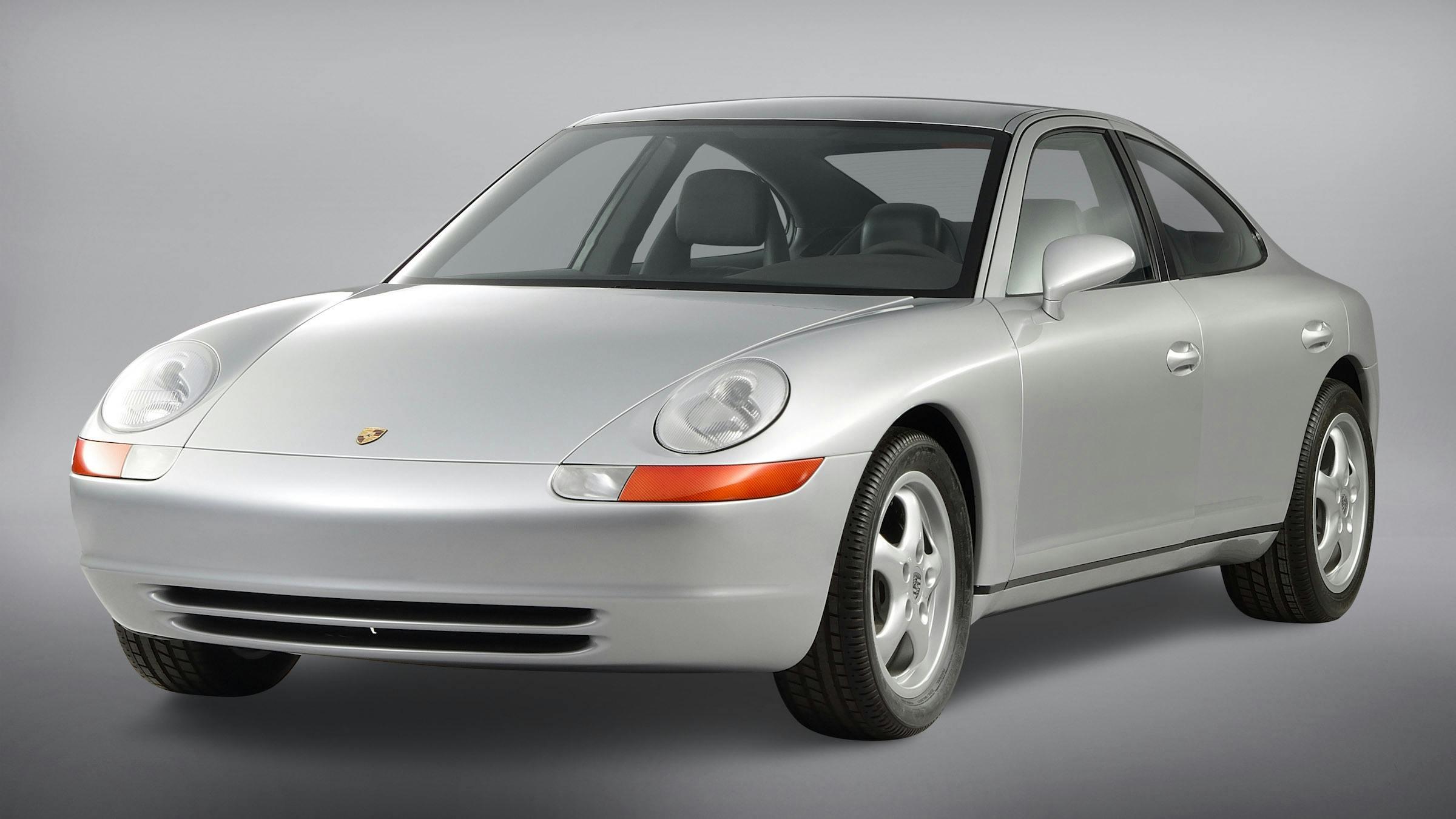

The 989 project—intended for launch in ’95—kicked off in early 1990. Harm Lagaay’s design team worked simultaneously on the ’94 model year (993) facelifted 911 and the 968 nip-and-tuck of the 944. As the only all-new design, the four-door 989 moved Porsche’s design language forward. It helped inspire the 968’s softening of the 944’s geometric forms and drew upon the delightful bisecting shutlines around the front lamps that defined the 993.

BMW frequently called upon the talents of Italdesign, Bertone, and Pininfarina as a sense check against their internal teams. It was Italdesign that Porsche commissioned to submit an alternative to the three similar-but-different submissions created under Lagaay. The Italians created something more SEAT than Porsche-like; there was no contest when the four options were lined up together in early ’91.

The task now was to refine the 989’s design, toughening up the front a little here, adding an attractive angled surface at the rear there, and finalizing the interior. Meanwhile, a Mercedes W124 E-Class was commandeered as a test hack to try out the new V-8 engine in its earliest form. (The Porsche/Audi–powered Mercedes is still retained by the Porsche Classic museum today, and it’s evident that this was very much a first-generation test vehicle.)

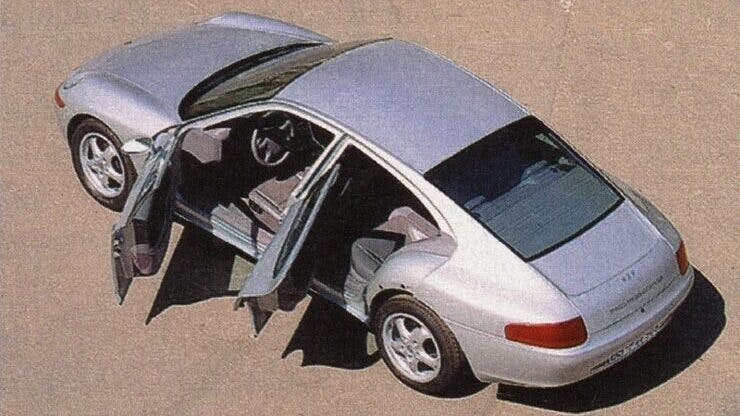

With suspension and powertrain engineering underway, the 989 project was moving along nicely during 1990. A definitive, “inside-out,” full-sized model was completed. It looked 99 percent like a fully drivable car, but the sleek bodywork was fiberglass rather than metal and the supporting chassis made of humble steel frame and boxwood.

When photographs emerged many years later of the 989 model wearing a registration plate, the assumption was that the 989 had been road-ready, but no, it was just for internal display.

The chilly financial winds that started blowing around Porsche in the late ’80s were whipping the company into potential oblivion by early ’91. BMW’s Wolfgang Reitzle approached the Porsche families with an offer to buy the ailing sports-car company, but their asking price of $600 million was too high. Instead, BMW sunk an even greater fortune into Rover.

Porsche needed the 989 to save the company, but costs were spiraling out of control. The projected price in today’s money was $180,000—that’s twice the price of a Panamera today—and Porsche needed to sell 15,000 units a year, nearly four times the number of M5s that BMW was shifting.

It didn’t take an MBA to see that the sums simply didn’t stack up. The super-saloon car market of the time was a fraction of what it would later became, and the 989 with its sleek, coupé-like looks would have obviously struggled against the commodious Mercedes S-Class, or the practical E500 that, perhaps ironically, Porsche helped engineer.

Politics were hardly helped by the fact that Ferdinand Piëch, one the highest-profile members of the Porsche family, happened to be the CEO of Audi. Since Porsche family members were not allowed to influence the running of the company, imagine how conflicted Piëch felt at being asked to surrender Audi’s V-8 motor to a competitor started by his grandfather.

Crunch time for the secret-saloon project

There is a crucial point in the vehicle development process. It’s not when the prettiest model is selected, or when the first engineering mules start running, but when the tooling needs to be ordered. Clay models and test cars might cost a four-to-six-figure sum, but Porsche, so strapped for cash in 1991, would have had to shell out millions to tool up for the 989. All this for a model that shared almost nothing with other vehicles in the range.

Porsche had no choice; the risk was too great. Though the car looked terrific, you only had to add a few Porsche-priced extras to get a four-door costing $200,000 in today’s money. Such a vehicle could only ever sell in small numbers. The project was officially scrapped in spring of ’91, and Ulrich Bez left the company soon after to join Daewoo, a client of the Porsche Engineering consultancy. The 320-hp V-8 engine was still under development but, like the car itself, was unfinished. For a while, Porsche toyed with it as a possible 911 power unit.

To a casual observer, the 989 looks like a four-door version of the 996-generation 911. But it’s not; the all-new 911 was launched in ’98, seven years after the 989 bit the dust. If anything, the 996 was stylistically more a two-door 989 than the other way around.

The 996-generation 911 and the 986 Boxster replaced the 989 as Porsche’s potential saviors. They were born from a different mindset—one learned from Toyota—and that philosophy ultimately rescued the company. By building two cars out of one common set of components, Porsche saved itself a fortune. The 989 could not have saved Porsche, but without it the 996 would not look the way it did. Perhaps its death was really a benefit, giving Porsche a badly needed focus and reality check, and ultimately living on in today’s 911 and 718 sports cars.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Too bad Porsche can’t resurrect the 989 with a few design updates. I have a (perfect) 2005 Carrera S cabriolet that still looks timeless, and to my eye -as an architect- the 989 was and is far handsomer than the current Panamera. With Porsche’s financial success and a changing demand for high-end cars, I think a new 989 could find a market.

Thanks for the video which laid out a lot of the explanation for the 924 and 944, and their reasons for being. I had a 924S in the early ’80s through ’94, and I always had to contend with the 911 crowd looking down their noses at my car (and thus me). But I new the truth – although it had started out as a cheap weaking, by 1980 and “S” designation, it was a helluva car. The statement that “if it weren’t for the 924 and 944, there would be no Porsche” is pretty strong, and I’m sure that Porsche Purists will scoff at it, but they were indeed important cars, if for no other reason than they sold in numbers great enough to fill the coffers at a time when Porsche really needed that ‘cheap car + high volume sales = bigger profit’ formula from something, anything.

I had had a ’67 911 and raced it in SCCA events, but honestly, I was “over” the 911 fascination by 1980 (still am). When I first drove that 924S, I was re-energized as a Porsche lover. An expensive divorce and resetting life’s priorities kept me out of the showroom after 1994, but I’m forever grateful to those VW parts bins for contributing the stuff it took to get the 924 up and going. I had an absolute blast in that car (and even blew off more than one 944 out on the freeway)! 😍

The 989 is a far better looking 4 door than any of the Panamera versions, which have always looked like a 928 rear ended a 911 to me.